Post-truth: Language and the trumping of objective reality by extreme partisan polarization

29 What is Post-Truth?

Introduction

Throughout this course we have already covered a lot of terrain clearly indicating the general theme that “we have entered a phase where facts are radically devalued in favour of shallow appearances and confirmation bias, fuelled by the meteoric rise in our usage of online social media over the last decade” (Morris, 2021, p. 320). Indeed, a lot of the separate sections have invoked the term ‘post-truth’ or indicated a connection to it. However, as clarified by Macnamara, “post-truth is not the same thing as, or another form of, fake news or disinformation. The condition of post-truth refers to a community or society in which personal beliefs and opinions are held as more important than facts and even scientific data. It denotes the normalization and acceptance of fake news, misinformation, and even disinformation and the resulting social and political decay” (2020, p. 131). Essentially, “post-truth rhetoric substitutes emotive, populist appeals for reasoned debate and academic expertise” (Oliver, 2020, p. 34).

Definitions

“Post-truth: the conviction that what one thinks and especially how one feels can change a lie into something truthful” (Glăveanu, 2022)

More circumscribed in its framing, Kalpokas argues, “Post-truth is perhaps best described as a manifestation of ‘a qualitatively new dishonesty on the part of politicians’ who, instead of being merely economical with the truth, ‘appear to make up facts to suit their narratives’” (2020). As a result, we now exist in a world where distinctions between facts and falsehoods no longer hold as “what matters is only public preference for one set of facts over another”.

History

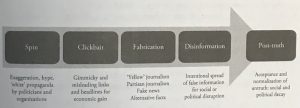

Even though the Oxford dictionary declared it their word of the year for 2016, the political rhetoric that merits the new term is quite a bit older.[2] It is rooted in tactics designed to ensure deniability, and in contemporary politics, the label (or even the notion of it) seems “to free politicians from the burden of being well-informed, accurate or even honest (Oliver, 2020, p. 18). The present situation isn’t simply one where the public doesn’t trust politicians, but one in which we don’t expect them to tell the truth at all (in addition to bandying about requisite amounts of bullshit). “The real concern of the present era is that a crisis of the trusted authorities of the past has fostered a social and political condition plagued by suspicions and skepticism, and replete with conflicting narratives, dishonesties, inaccuracies, and false or fabricated information” (Cosentino, 2020, p. 19). Post-truth, as a social condition, is a relatively recent phenomenon (unlike propaganda that has been with us at least as long as information has been ‘propagated’, and fake news, that has existed as long as we have had journalism). It is a sensibility brought on by an evolution in media and language claims, typified by Macnamara (2020, p. 131) in the following fashion:

Speaking of public relations in a post-truth environment, Thompson argues that post-truth is, “a social condition that arises from two communication behaviours: (1) The willingness of senders of messages to use falsehoods in public communication in order to win debates and influence opinion; (2) The willingness of audiences to accept the “truthy” messages and informational propositions of senders whose messages suit their opinions” (2020, p. 87). So the truthiness/truth decay that we addressed in the last unit are definite building blocks of the post-truth era. It’s not just nomenclature; it’s an epistemic revolution whose foundation has been quietly being built for quite some time.

In the end, perhaps “we have always dwelled, to some extent, in the realm of heightened possibility that is post-truth. But the difference today is that not only individuals do this – entire communities engage in such practices as well” (Glăveanu, 2022).

Varieties

Typically, there are lots of different forms of our objects of inquiry … here is where we start to distinguish them…

Type 1

this is the main way of seeing …

Type 2

…

Philosophically, post-truth is aligned with certain tenets of postmodernism. The eclipse of metanarratives and the rise of micro-narratives (a la Lyotard) suggest a fundamental pivot point.

However, as Harsin points out, while concepts such as Baudrillard’s simulacra resonate with post-truth, what is missing are “problems of competing trust, authority, bias, political polarization, algorithmically customized experiences with perceptual and epistemic repercussions and other topics at the heart of post-truth conditions and theory” (2018). Post-truth is aligned with (and arguably indebted to) certain precepts of postmodern thinking but it is a distinctive mode of engagement.

Similarly, post-truth is not wholly dependent upon social media, but it is difficult to conceive of the 21st century phenomenon without them. Hannan provocatively argues that we are trolling ourselves to death and frames the problem of post-truth politics not by focusing on the media, or journalism (as Harsin did) but by focusing on media, or the technologies of communication: “The atmosphere of social media has become so poisoned by incivility that trolling can rightly be said to be the new normal, as regular to our political atmosphere as the air we breathe. It is a tense environment in which disagreements, even between friends, quickly descend into vicious battles, very often destroying those friendships in the process” (2018, p. 7). The technological determinism is laid bare in the following lengthy description of how public discourse appears to have broken down into an alternate universe of ‘brazen lies and grotesque spectacles of immaturity, incivility and obnoxiousness’:

In a discursive economy in which the basic unit of currency is a status update, popularity often carries more persuasive power than the appeal to impersonal fact. Indeed, being too factual, being too thorough and meticulous in a disagreement on social media, is a recipe for ‘tl;dr’ (‘too long; didn’t read’). Lengthy, detailed disquisitions do not fare very well against short, biting sarcasm. They also do not fare well against comments that, however inane, rack up a far greater number of likes. In the mental universe of social media, truth is a popularity contest. (Hannan, 2018, p. 7)

Context & Connections

Like our earlier discussion of digital and computational propaganda, “what distinguishes the current post-truth era is … the reach and the speed that characterize the circulation of deceptive communications” (Cosentino, 2020, p. 17). Citing the Italian scholar Franco Beraardi, Cosentino elaborates upon this nuance: “The acceleration of the info sphere … has saturated the attention and has consequently disabled society’s critical abilities” (2020, p. 17). If one believes that truth is still relevant (even if it’s contextually defined), “the post-truth problem is not the truth itself but people’s ability to handle it” (Fuller, 2017, p. 480).

In order to understand post-truth and connect it to what we have been talking about through each chapter, it is important to take a look back at Harry Frankfurt’s conceptualization of bullshit and how it applies to the political sphere of post-truth. Frankfurt makes the key distinction between lies and bullshit:

“Telling a lie is an act with a sharp focus. It is designed to insert a particular falsehood at a specific point in a set or system of beliefs, in order to avoid the consequences of having that point occupied by the truth. This requires a degree of craftsmanship, in which the teller of the lie submits to objective constraints imposed by what he takes to be the truth. The liar is inescapably concerned with truth-values. (Frankfurt 2005)

Frankfurt’s ideas on bullshit and bullshit itself flourishes in the realm of political post-truth. It is important to note the ways in which ideas and discourses shape social interests and to consider that much political discourse is bullshit (Hopkin., Rosamond., 2018). We are in a world where a lot of information is bullshit and a person’s ability to distinguish the truth has become extremely difficult. But maybe trying to determine whether political claims-making is ‘true’ or not is not the most important thing (in a world where post-truth is taken to be the truth). After all, “an ascendant view among Trump’s critics is that charges of ‘bullshit’ might be more apt than of lies and lying, since the latter charges presume specific intent and awareness rather than a more constant tendency to exaggerate and deceive, sometimes for no apparent reason” (Lynch, 2017, p. 594). With this in mind, it is useful to draw themes from Frankfurt’s ideas on bullshit when examining post-truth and view the topic/era through a critical lens. Post-truth is not simply about lies and false beliefs (Harsin, 2018), but also about the widespread confusion brought on by an abundance of information and influential appeals. [B.R]

References

Cosentino, G. (2020).

Frankfurt H. (2005(. On Bullshit. Princeton University Press.

Fuller, S. (2017). The Post-Truth About Philosophy and Rhetoric. Philosophy & Rhetoric , 50(4), 473-482. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/philrhet.50.4.0473

Glăveanu, V. P. (2022). Post-truth. The Palgrave Encyclopedia of the Possible, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98390-5_256-2

Hannan, J. (2018). Trolling ourselves to death? Social media and post-truth politics. European Journal of Communication, 1–13.

Harsin, J. (2018) Post-Truth and Critical Communication. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.757

Hopkin, J., & Rosamond, B. (2018). Post-truth Politics, Bullshit and Bad Ideas: “Deficit Fetishism” in the UK. New Political Economy, 23(6), 641–655.

Kalpokas, I. (2020). Post-Truth and the Changing Information Environment. In P. Baines, N. O’Shaughnessy, & N. Snow (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Propaganda (pp. 71-84). Sage.

Lynch, M. (2017). STS, symmetry and post-truth. Social Studies of Science, 47(4), 593–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312717720308.

Macnamara, J. (2020). Beyond Post-Communication: Challenging disinformation, deception, and manipulation. Peter Lang.

Morris, J. (2021). Simulacra in the Age of Social Media: Baudrillard as the Prophet of Fake News. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 45(4) 319–336.

Oliver, M. (2020). Infrastructure and the Post-Truth Era: is Trump Twitter’s Fault? Postdigital Science and Education, 2:17–38 https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-019-00073-8

Thompson, G. (2020). Post-Truth Public Relations: Communication in an Era of Digital Disinformation. Routledge.

Feedback/Errata