Misinformation: The language of (unintentional) manipulation

10 What is misinformation?

Introduction

Misinformation – huge deal: Many Americans Say Made-Up News Is a Critical Problem That Needs To Be Fixed (2019 stats); Poll: Most in US say misinformation spurs extremism, hate (2022 stats), False news in the U.S. – statistics & facts (2024 stats)

Definitions

Misinformation is simply information that is false but spread by those without knowledge of its falsity. It has also been classified as “unintended communicative untruthfulness” (Hameleers & Minihold, 2022, p. 1177). Bergstrom and West succinctly classify it as “claims that are false but not deliberately designed to deceive” (2020, p. 29). Going into a little more detail, Lee and Jia suggest, “misinformation refers to content that is false but not intended to harm, ranging from unintentional mistakes such as misleading quotes and inaccurate image captions to satire when it is taken seriously” (2023, p. 30).

“Misinformation alludes to the existence of false information around a range of issues relevant to public life, including political, historical, health, social, and environmental matters, in the public” (Tumber and Waisbord, 2021, p. 1).

Misinformation can and often does occur accidentally, and may or may not cause harm” (Macnamara, 2021, p. 38). It can even be simply a nuisance, as the subtitle of one article suggested: “The Web of False Information: Rumors, Fake News, Hoaxes, Clickbait, and Various Other Shenanigans” (Zannettou et al., 2020). However, it can, of course, cause serious harm.

History

once upon a time …

Varieties

Typically, there are lots of different forms of our objects of inquiry … here is where we start to distinguish them…

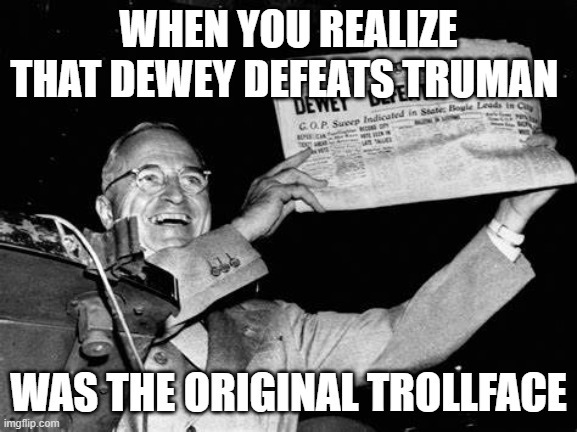

Fallis (2016, p. 333) suggests that misinformation comes in a many different varieties, resulting from honest mistakes (like the headline of The Chicago Tribune on November 3, 1948 mistakenly reporting Presidential election results).

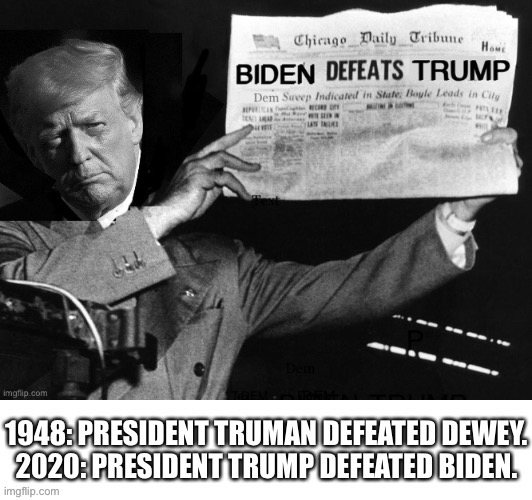

Incidentally, this is a fine example of how memes can be disinformation too (as the original has been remediated to fit contemporary times):

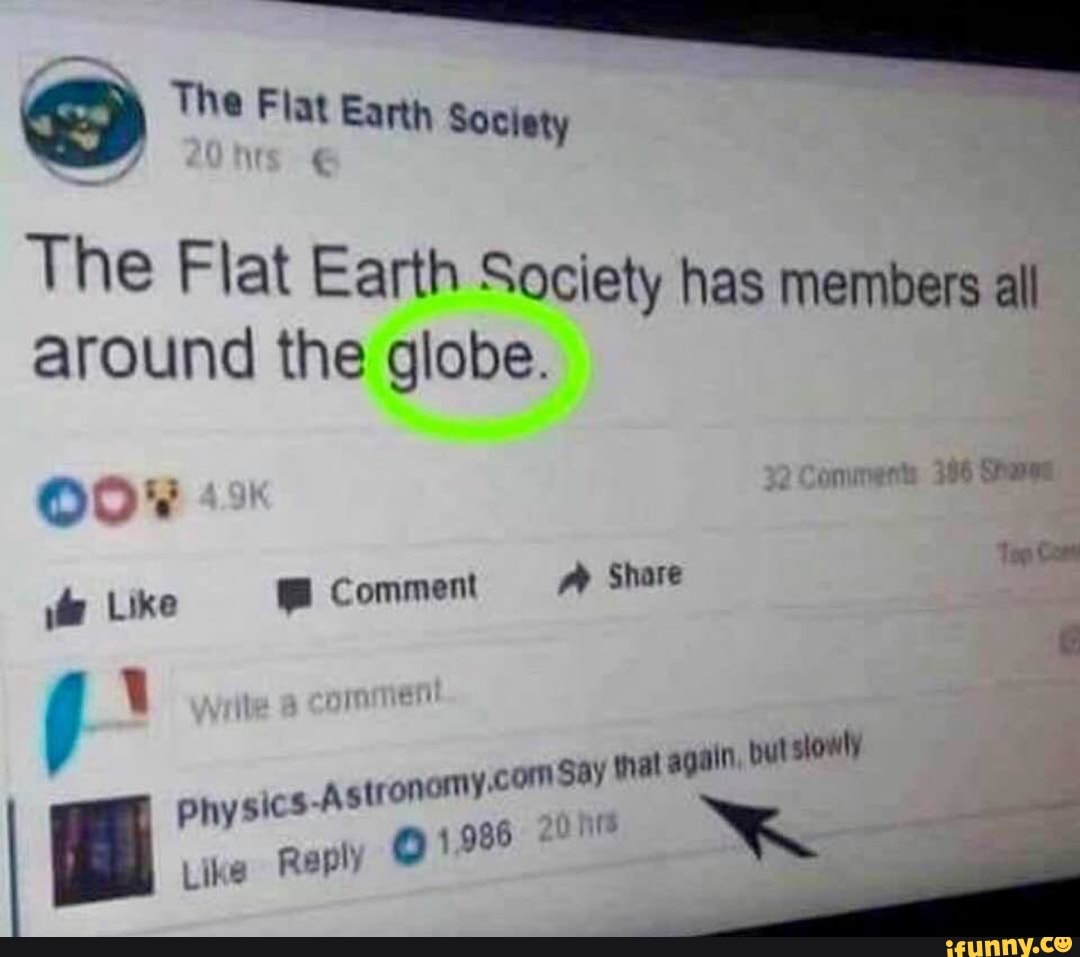

Misinformation can also result from ignorance (when one spreads false information because they don’t know any better or haven’t done their ‘homework’). And misinformation can result from unconscious bias (when one spreads information that they believe in because it fits with what they already believe, rather than because the evidence supports it). This can be seen in those who resist new information (like scientific findings about climate change, for instance) or those who maintain marginal views in the face of widespread information to the contrary (like flat earthers).

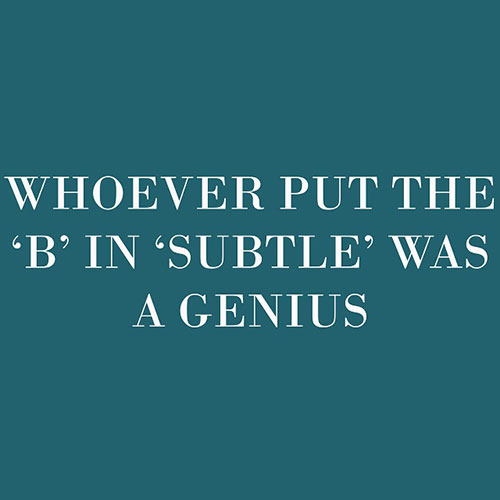

Subtle misinformation

Sometimes, misinformation is not explicit. Rather than being clearly false, “misinformation in the real world is often more subtly misleading, with misdirection resulting from information that is technically true but misleading in substance” (Ecker et al., 2014, p. 324).

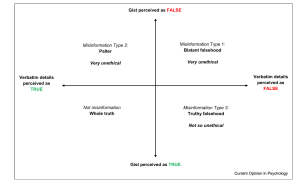

Research has shown that “people have a more-nuanced view of misinformation than the binary distinction between ‘fake news’ and ‘real news’ implies,” and that “people tolerate and intentionally spread misinformation in part because they believe its gist” (Langdon et al., 2024, p. 1). Gist communication is fascinating in that it sounds very bullshit-y: “Gist lies between, on the one hand, utterly neutral and often meaningless facts (e.g., is a 22% risk of cancer high or low) and, on the other hand, persuasion which attempts to change beliefs or values” (Reyna, 2021, p. 3). In terms of ‘getting the gist of something,’ but spreading it, even if it is false (bit not intending to cause harm), we can see three different types of misinformation: the blatant falsehood, palter (misleading while technically saying the truth, often through equivocation — historically, it is associated with the word ‘paltry’ meaning insignificant or trivial…), and truthy falsehood (Langdon et al., 2024):

This idea of “gist truth” will be reintroduced in the unit on truth, later…

Rumors

Rumors can be understood as a particular type of misinformation, especially if one uses Knapp’s definition of a rumor as “a proposition for belief of topical reference disseminated without official verification” (1944, p. 22). Knapp states that rumors are based around specific cases of information spread in social communications, typically seen in interpersonal communication (person-to-person). While much of this article bases rumor information around war/post-war affects and characteristics, it still provides a good foundation for understanding rumors, especially if we understand rumors as ‘unsubstantiated information’, spread so easily in an era of social media (Starbird et al., 2014).

Three very basic characteristics of rumors are defined. (1) mode of transmission: mostly by word of mouth. (2) Rumors will provide ‘information’: always specific about something, someone, somewhere; always something specific. (3) Rumors satisfy: rumors work from the emotional gratifications they afford, called the ‘expressive’ characteristic, they fulfil emotional needs of a community. Rumors do not always follow both of the last two characteristics, some are primarily informative, and some are primarily in the interest of emotional satisfaction. (Knapp, 22-23).

Three basic types of rumors are outlined as well. Not characteristics of a rumor, but types/ categories of a rumor. (1) The pipedream or wish rumor: expresses wishes and hopes of those spreading, or ‘wishful thinking’. (2) The bogie rumor: opposite to type one, these expresses fear and anxieties. (3) The wedge-driving or aggression rumor: divides groups and destroys loyalties, motivated in aggression or hatred, almost always seen against one’s own population/group/community/allies. (Knapp, 23-24).

Rumors exist in this information distortion realm. For instance, Knapp’s third characteristic of satisfying an emotional need, fear or panic connects to the concept of ‘alarmist narratives’ on misinformation (L’Etang, 2008, p. 5). If you were to classify the concept of alarmist narrative rumors with Knapp’s types of rumors, it would be either type two or three; the bogie rumor or the wedge-driving or aggression rumor. Due to the alarmist narrative basing on fear of dangers, this is driven through negative emotions which link to type two or three of rumors. Through this concept, misinformation that turns into rumors are based in fear and anxieties and are spread through these shared fears and anxieties or towards the spreader’s own community with malicious intent to divide or destroy. [BC- References below]

Type 3

political misinformation

health misinformation

sports misinformation (see https://frontofficesports.com/the-spread-of-sports-misinformation-on-x-is-increasingly-apparent/

weather (climate) misinformation (see the evocatively titled blog entry (with a great link to a story by The New York Times), When the Storm Online Is Worse Than the One Outside)

…

Misinformation can also take on many forms quite distinct from strictly text-based materials. Memes, for instance, combine text with images with the image forming an important part of the overall appeal. Doctored images and videos (deepfakes) can also be incredibly difficult to determine whether they are truthful or not and thus get spread easily.

Context & Connections

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/americans-agree-misinformation-is-a-problem-poll-shows (example of the third-person effect)

see also: THE AMERICAN PUBLIC VIEWS THE SPREAD OF MISINFORMATION AS A MAJOR PROBLEM (2021 summation, similarly displacing blame onto politicians and social media companies) Ninety-five percent of Americans identified misinformation as a problem when they’re trying to access important information. About half put a great deal of blame on the U.S. government, and about three-quarters point to social media users and tech companies. Yet only 2 in 10 Americans say they’re very concerned that they have personally spread misinformation.[1]

It is not coincidental that concerns over mis (and dis) information run rampant alongside the burgeoning content factories known as social media. “Social media facilitates the spread of misinformation. … On social media platforms, the first outlet to break a story receives the bulk of the traffic. In the race to be first, publishers often cut any fact-checking out of the publication process. You can’t beat your competitors to press if you pause to rigorously fact-check a story. Being careful is admirable, but it doesn’t sell ads.” (Bergstrom & West, 2020, p. 29). Just as information has always been present in human society but amped up in importance in an ‘Information Age’, so too has misinformation always been a concern, but the scale (and social significance) of it has changed with the internet and social media in particular (see Macnamara, 2021, p. 48).

And I really don’t want to fall into the trap of saying ‘It’s all subjective,’ but “whether a given story or piece of content is labeled as misinformation or disinformation can depend as much on an actor’s intent as on the professional standards of the person evaluating it” (Jack, 2017, p. 4). But clarifying that distinction is where we go in the next unit…

The Spread of Misinformation and Cultural Attraction Theory

Expanding upon the above passage, alarmist narratives have played a significant role in raising awareness about the prevalence of misinformation. But why exactly have these alarmist narratives been a large contributor to the realization of misinformation? According to Altay and Acerbi, “To understand why people are so worried about misinformation, and ultimately why alarmist narratives on misinformation have gained so much traction, we draw on the field of cultural evolution” (Altay and Acerbi, pg. 3, 2023). Cultural Attraction Theory draws on the intuitive cognitive mechanism that places an emphasis on ideas or beliefs that are attractive to the consumer (Altay and Acerbi, pg. 3, 2023). Typically, ideas or beliefs that are attractive to someone are memorable and attention-grabbing; and often something is memorable and attention-grabbing because of the emotion it evokes in someone (Koch, 2010). Alarmist narratives tend to create an emotional response out of the consumer by using a mix of volatile emotions, such as fear and uncertainty, to provoke strong reactions thereby facilitating the rapid dissemination of the narrative through social and traditional media channels (Faster Capital, 2024).

One clear manifestation of alarmist narratives is found in sensational headlines. “Sensational headlines and exaggerated narratives grab attention, leading to higher viewership or readership. As a result, media outlets might prioritize alarming stories over balanced, nuanced reporting, contributing to the spread of fear” (Faster Capital, 2024). Discovered in a study conducted by Ecker et al., “Information presented in news articles can be misleading without being blatantly false. Experiment 1 examined the effects of misleading headlines that emphasize secondary content rather than the article’s primary gist” (Ecker et al., pg. 323, 2014). Their research uncovered how people tend to accept information from headlines as valid, especially when there is a strong emotional connection felt in response to reading the headline (Ecker et al., pg. 323, 2014). However, because of the emotional reactions created by these headlines, even when the information or meaning of the headline is corrected to represent the truth of the article the reader’s perception of the topic is already skewed enough to the point where the corrections are often ineffective (Ecker et al., pg. 332, 2014). “The effects of misleading headlines are likely to arise concurrently from multiple cognitive mechanisms. First, readers use available information to constrain further information processing. This means that any incoming evidence will always be weighted and interpreted in light of information already received, and a headline can thus serve to bias processing toward or away from a specific interpretation” (Ecker et al., pg. 332, 2014).

However, the challenge arises when the acknowledgment of misinformation’s online prevalence, creates panic and distrust regarding seemingly true information because of skepticism and lack of trust created by rampant alarmist narratives. Alarmist narratives surrounding misinformation further exacerbate this dilemma, fostering a general sense of mistrust in information dissemination. “If alarmist narratives on misinformation were to successfully increase the perceived prevalence of misinformation (which remains to be proven), they could lead to narrower media diets, less trust in the media, and reduce the sharing of reliable news on social media” (Altay and Acerbi, pg. 2, 2023). Social media platforms, with its ease of use, anonymity, accessibility, and participatory nature, play a pivotal role in shaping individuals’ perceptions of various issues (Acerbi, pg. 9, 2019), and in an era of information overload, the question of truth becomes increasingly elusive. The notion of misinformation itself has become an alarmist narrative, further complicating matters. Should we allow our emotions to dictate our consumption and acceptance of information, or should we adopt a more discerning approach that is cognizant of the potential for misinformation and purposefully crafted content? The choice is yours!

Works Cited

Acerbi, A. (2019). Cognitive attraction and online misinformation. Palgrave Communications, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0224-y

Altay, S., & Acerbi, A. (2023). People believe misinformation is a threat because they assume others are gullible. New Media & Society, 146144482311533. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231153379

Ecker, U. K., Lewandowsky, S., Chang, E. P., & Pillai, R. (2014). The effects of subtle misinformation in news headlines. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 20(4), 323–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000028

Faster Capital. (2024). Alarmism: When alarmism takes over: The dangers of overreacting. FasterCapital. https://fastercapital.com/content/Alarmism–When-Alarmism-Takes-Over–The-Dangers-of-Overreacting.html

Koch, C. (2010, February 20). You must remember this: What makes something memorable?. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/you-must-remember-this/#:~:text=Scientists%20know%20that%20many%20factors,of%20emotions%20that%20are%20evoked.

[cz]

References

Bergstrom, C. T., & West, J. D. (2020). Calling bullshit: The art of skepticism in a data-driven world. Random House.

Ecker, U. K. H., Lewandowsky, S., Chang, E. P. & Pillai, R. (2014). The effects of subtle misinformation in news headlines. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 20 (4), 323–335.

Fallis, D. (2016). Mis- and dis-information. In L. Floridi (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of philosophy of information (pp. 332-346). Routledge.

Hameleers, M., & Minihold, S. (2022). Constructing Discourses on (Un)truthfulness: Attributions of Reality, Misinformation, and Disinformation by Politicians in a Comparative Social Media Setting. Communication Research, 49 (8), 1176–1199.

Jack C. (2017). Lexicon of lies : Terms for problematic information. Data & Society. Retrieved from https://datasociety.net/pubs/oh/DataAndSociety_LexiconofLies.pdf

Knapp, R. H. (1944). A Psychology of Rumor. Public Opinion Quarterly., 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1086/265665

Langdon, J. A., Helgason, B. A., Qiub, J., & Effron, D. A. (2024). “It’s Not Literally True, But You Get the Gist:” How nuanced understandings of truth encourage people to condone and spread misinformation. Current opinion in psychology, 57:101788, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2024.101788

Lee, T., & Jia, C. (2023). Curse or Cure? The Role of Algorithm in Promoting or Countering Information Disorder. In M. Filimowicz (Ed.), Information Disorder: Algorithms and Society (pp. 29-45). Routledge.

L’Etang, Jacquie (2008). “Public Relations, Persuasion and Propaganda: Truth, Knowledge, Spirituality and Mystique.” In Ansgar Zerfass et al. (eds.), Public Relations Research: European and International Perspectives and Innovations (pp. 251–269).

Macnamara, J. (2021). Challenging post-communication: Beyond focus on a ‘few bad apples’ to multi-level public communication reform. Communication research and practice, 7 (1), pp. 35–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2021.1876404

Reyna, V. F. (2021). A scientific theory of gist communication and misinformation resistance, with implications for health, education, and policy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118 (5), https:// doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1912441117.

Starbird K., Maddock J., Orand M., Achterman P., & Mason R. M. (2014). Rumors, false flags, and digital vigilantes: Misinformation on twitter after the 2013 Boston marathon bombing. Iconference 20 Proceedings, 14, 654–662.

Tumber, H., & Waisbord, S. (2021). Introduction. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Media Disinformation and Populism (pp. 1-12). Routledge.

Zannettou, S., Sirivianos, M., Blackburn, J, & Kourtellis, N. (2020). The Web of False Information: Rumors, Fake News, Hoaxes, Clickbait, and Various Other Shenanigans. ACM journal of data and information quality, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.1145/3309699

- https://apnews.com/article/coronavirus-pandemic-technology-business-health-misinformation-fbe9d09024d7b92e1600e411d5f931dd ↵

Feedback/Errata

2 Responses to What is misinformation?