Disinformation: The language of (intentional) manipulation

15 Examples and Case-Studies in Disinformation

An example I mentioned in class, could definitely be developed further…

https://globalnews.ca/news/10289988/lululemon-greenwashing-claims-environmental-groups/

https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/lululemon-competition-bureau-claim-1.7114286

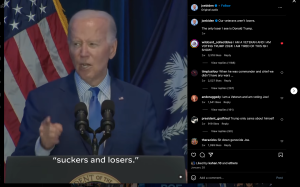

Joe Biden Rebukes False Trump Quotes, Calls Out Emotional Manipulation in Disinformation

President Joe Biden Official Instagram Account

https://www.instagram.com/reel/C2pwW8NLkbq/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

During a public appearance before the media, Joe Biden made a public statement in which he quoted Donald Trump and stated that Trump referred to veterans and patriots as “suckers and losers.” In addition, he stated that he did not go to the United States cemetery, which is a fact due to different reasons; however, there is no evidence to suggest that he referred to the people there as “suckers and losers.” for the purpose of imbuing the entire message with an emotive and thematic quality. When Joe Biden brought up the passing of his son, he retorted, “How dare he say that! You can’t call my son a loser”.

VB

Example 2

Disinformation during World war II

D. J.

Disinformation is a wide-ranging problem that has many forms, dating back hundreds of years. Between the years of 1943- 48 Mieczyslaw Stachowiak’s, a Polish citizen was involved in the creation and spread of disinformation during World War II. His disinformation included fabricating information about espionage activities, and secret missions, and even claiming to have information about the whereabouts of the missing Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg. This circulation was deliberate and always for his benefit, and he exchanged this disinformation for money. Stachowiak’s wasn’t just a facilitator he spread, “false intelligence to five foreign diplomatic missions in Sweden – Britain, Germany, Japan, Spain and the United States – and provided them with false intelligence in return for money (Matz, 2015).” This demonstrated that there is a systematic distribution taking place. This disinformation campaign had real-life consequences, such as “claims regarding Polish anti-German espionage activities, a secret Soviet espionage mission to the US, Soviet military support to adversaries of the Franco regime in Spain and information on the whereabouts of the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg (Matz, 2015).” People died and lived, where fighting would take place and how missions were taking place were dictated by the disinformation from Stachowiak’s, highlighting real-world diplomatic and operational consequences of the spread of disinformation. Even in the present day, it is difficult to find the source of misinformation without becoming fascinated by the medium that is used to promote it. This is demonstrated by the lengthy search for Stachowiak, who was at the centre of the creation and travel of the disinformation. Even when he was taken in, the authorities were unwilling to admit that he was working for the Soviets, and not only for his own benefit, due to the difficulties in tracing and determining the objective of misinformation efforts.

References

Matz, Johan. “Intelligence and Disinformation in World War II and the Early Cold War 1943–48: Stachowiak Alias Drauschke Alias Donoa, His Intelligence Activities in Sweden and Denmark, and the Raoul Wallenberg Case.” Journal of Intelligence History 14, no. 1 (January 2, 2015): 16–37. doi:10.1080/16161262.2014.973170.

Artificial Intelligence-based Software Helps Steal $243,000 from U.K.-based Energy Firm

In 2019, artificial intelligence technology was used to rob a U.K. energy firm of $243,000. The CEO of this energy firm was on the phone with the firm’s German parent company talking about sending funds to a Hungarian supplier. As it turns out, the person that the CEO was talking to was not a person at all, but was an artificial intelligence-based software.

The U.K. CEO said that he “recognized his boss’ slight German accent and the melody of his voice on the phone” (WSJ Pro, 2019). This impersonation of the executive’s voice using A.I led to the CEO transferring $243,000 to somewhere other than the Hungarian fund that it was intended for. The money was “moved to Mexico and distributed to other locations” (WSJ Pro, 2019), ultimately leaving the U.K. energy firm with a bank account missing $243,000.

This incident is just one example of how disinformation can be identified in A.I. technologies. Noémi Bontridder and Yves Poullet (2021) note that A.I techniques “boost the disinformation phenomenon online in two ways. First, AI techniques are generating new opportunities to create or manipulate texts and image, audio, or video content. Second, AI systems developed and deployed by online platforms to enhance their users’ engagement significantly contribute to the effective and rapid dissemination of disinformation online” (Bontridder & Poullet, 2021). The first way mentioned is very important because it shows that by just using A.I voice technologies, it can be detrimental to spreading disinformation.

So, shown by this 2019 incident of an A.I. mimicking a CEO’s voice, it highlights the alarming potential of A.I. technologies to facilitate disinformation, posing risks not only to financial security but also contributing to the rapid dissemination of false narratives in various online platforms. [BR]

References

Stupp, C. (2019, August 30). Fraudsters Used AI to Mimic CEO’s Voice in Unusual Cybercrime Case. Wall Street Journal Professional. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/fraudsters-use-ai-to-mimic-ceos-voice-in-unusual-cybercrime-case-11567157402

Bontridder, N., & Poullet, Y. (2021). The role of artificial intelligence in disinformation. Data & Policy, 3(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/dap.2021.20

Dietitians are being paid to spread disinformation about food on social media?

As social media continues to rise in both use and popularity, it becomes far easier for disinformation to spread rampantly (Tandoc et al., 2020). This phenomenon is especially true for news consumption, and how people navigate fake news and disinformation regarding the content that is continuously being shown to them online. Tandoc et al. (2020) explain how many recent studies address these issues, specifically referring to false information which is packaged to look like news or information to deliberately mislead viewers or followers. With the sheet amount of content on social media platforms, it becomes easy for users to be overloaded with information not knowing or caring whether or not the information they’re receiving is legitimate.

Many prime examples of disinformation can be observed on social media, especially in recent times where social media has become more prominent, accessible, and important in everyday life. As more people obtain their news and information from social media, and more everyday citizens begin to post to social media, it becomes easier for disinformation to be spread amongst these platforms. Tik Tok has recently become a major source of both disinformation and misinformation, which can be easily circulated amongst users of the platform. A recent example of disinformation on Tik Tok is how dietitian influencers are seemingly being paid by the food industry to spread disinformation about dietary advice, including certain foods and their health benefits, or lack thereof (O’Connor et al., 2023). These dietitians on Tik Tok are spreading false information which goes directly against what is being stated by the World Health Organization. The WHO has recently put out warnings regarding aspartame and artificial sweeteners, and many dietitians have taken to social media stating that these claims are false in order to promote foods that contain artificial sweeteners. As media becomes increasingly more digital, the dangers of disinformation become increased as well; in many cases it becomes extremely difficult to detect disinformation, especially when it comes from sources which are believed to be trusted.

[R.L]

References

O’Connor, A., Gillbert, C., & Chavkin, S. (2023). The food industry pays ‘influencer’ dietitians to shape your … The food industry pays ‘influencer’ dietitians to shape your eating habits. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wellness/2023/09/13/dietitian-instagram-tiktok-paid-food-industry/

Tandoc, E. C., Lim, D., & Ling, R. (2020). Diffusion of disinformation: How social media users respond to fake news and why. Journalism, 21(3), 381-398. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919868325

The Disinformation Campaign of ‘Hillary’s Health’ and Its Broader Implications

Disinformation refers to intentionally misleading or false information spread to deceive or manipulate public opinion or behaviour. This contrasts with misinformation, which is also false but not spread with malicious intent (Hameleers, 2022). The case of “Hillary’s Health” exemplifies classic disinformation due to the deliberate fabrication and circulation of false narratives regarding Hillary Clinton’s physical and mental health during the 2016 presidential campaign. (Marwick & Lewis, 2020) The disinformation tactics employed in the “Hillary’s Health” campaign begins with the initial spread of false claims by far-right bloggers, who circulated conspiracy theories about Hillary Clinton’s health based on out-of-context videos. These claims, suggesting severe health issues, were then amplified by influential figures like Paul Joseph Watson, reaching a wider audience.

The narrative gained further traction as mainstream media outlets, including the Drudge Report and Fox News, covered the story, inviting speculation without outright endorsement of the theories. Social media platforms played a pivotal role in amplifying the disinformation, with hashtags and mocking content spreading rapidly. The situation escalated when Clinton’s departure from a 9/11 memorial event, later attributed to pneumonia, was seized upon by social media users and conspiracy theorists as evidence of a cover-up, despite medical reports to the contrary.

Mainstream media’s continued speculation and raising of “unanswered questions” about her health further entrenched public doubt, demonstrating how disinformation can perpetuate itself through a combination of initial fabrication, amplification by influencers, media coverage, social media mockery, manipulation of real events, and reinforcement by the media, thereby completing the cycle of disinformation. The strategy behind this disinformation campaign aligns with the intent to harm or disadvantage an individual, in this case, Hillary Clinton, by undermining public trust and influencing voter perception.

The spread of disinformation in this example exemplifies several crucial points raised in scholarly discussions about the subject. First, the involvement of prominent players and networks in reinforcing false narratives highlights the need of deliberateness in disinformation tactics. According to (Hameleers, 2022), Individuals and groups with political agendas devised and propagated these falsehoods to achieve specific goals, in this example to hurt Clinton’s electoral prospects.

Furthermore, the strategic use of disinformation in this case involved the amplification of false theories into mainstream discourse, demonstrating the “networked logic” of disinformation’s dissemination. The spread from conspiracy-theory-driven blogs to mainstream conservative outlets and then to broader public discussion illustrates how disinformation leverages both digital platforms and traditional media to gain credibility and reach. This process not only muddies the waters of public discourse but also exploits and exacerbates existing socio-political divisions, aiming to destabilize trust in individuals and institutions (Hameleers, 2022).

In summary, the “Hillary’s Health” case study exemplifies disinformation’s dangerous ability to shape political narratives, manipulate public opinion, and impact democratic processes. It emphasizes the significance of critically assessing the sources, motivations, and consequences of such efforts in the larger socio-political context. This understanding is critical in devising tactics to counteract disinformation and safeguard the integrity of public debate and democratic institutions. [H.P]

References:

Hameleers, M. (2022). Disinformation as a context-bound phenomenon: Toward a conceptual clarification integrating actors, intentions and techniques of creation and dissemination. Communication Theory, 33(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtac021

Lewis, B., & Marwick, A. E. (2017, May 15). Media manipulation and disinformation online. Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/library/media-manipulation-and-disinfo-online/

Volkswagen Diesel Emissions Scandal:

Worldwide, Volkswagen installed a diesel emissions software on roughly 10.5 million cars that allowed all cars fitted with the software to be able to be compliant with diesel emissions regulations worldwide. This device was clearly something that was not advertised to consumers or dealerships, meaning that it was something that was clearly known by the designers of the vehicle that was not allowed to be placed in vehicles. Considering that the designers of the vehicles knew that this had been implemented and they kept it secret, they were very clearly aware that what they had done would have significant repercussions. This was something that was intentionally misleading a mass audience while being known by the manufacturer. Because of this, this can be classified as disinformation. These cars were immensely popular throughout the world, so much so that the U.S district court approved the buyback for customer cars at a $14.7 billion settlement. This shows the enormous amount of vehicles that were sold with the cheating software. Seeing the mass amount of people that were mislead by the emissions ratings of these cars shows the danger of mass disinformation and how susceptible the public is to it.

Atiyeh, C. (n.d.). Everything you need to know about the VW diesel-emissions scandal. https://www.caranddriver.com/news/a15339250/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-vw-diesel-emissions-scandal/

Feedback/Errata