Truth: Language and how we come to believe what we think we know

26 What is Truth?

Introduction

Why do we have a section on “the truth” in a course dedicated to persuasion, propaganda, and manipulation of language (and maybe, the subsequent manipulation of the public, using that language…)? Don’t facts and logical assessment thereof suggest what is true and what is false? Can’t we all agree on that? Apparently not. The whole idea of a “post-truth” era came to a head when, in 2018, President Trump’s lawyer declared “Truth isn’t truth”:

It’s too easy to say that the opposite of truth is lies/falsehood. This isn’t the case, however, in a world where bullshit is so thoroughgoing and taken-for-granted as a factor of public life. In a course objectively about propaganda and misinformation, we take seriously the prevalence of bullshit, the communication byproduct of “fakers and phones who are attempting by what they say to manipulate the opinions and the attitudes of those to whom they speak” (Frankfurt, 2018, p. 4). And bullshitters take a very pragmatic (re. flexible) view of the truth. They obfuscate and bend facts in pursuit of their objective, indifferent to whether what they say is true or whether it is false” (Frankfurt, 2018, p. 4). But this is only a bad thing if one considers that “being indifferent to truth is an undesirable or even a reprehensible characteristic, and bullshitting is therefore to be avoided and condemned” (Frankfurt, 2018, p. 5). It would seem that this is not necessarily a universally agreed-upon sentiment.

“What is truth? How can we know it? Does truth refer to reality or is it merely a social construction? Do we possess objective knowledge of the world or is knowledge always subjective? These unresolved philosophical questions create uncertainty in our approach to truth. After all, if there are no objective facts and if truth is always relative to a perspective, does it follow that there are alternative conceptions of reality? Those who think that truth is relative and socially constructed cannot complain when post-factualists like Trump take a different view of truth” (Zoglauer, 2023, p. x).

The waning of the truth due to the increased contestation of it occurs alongside the rise of its traditional opposite, falsehood: “There is a growing body of research pointing to falsehoods diffusing significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth in nearly all studied categories of information” (O’Hara, 2022, p. 3). To be frank, we live in a world where the phrase “being economical with the truth” no longer means to be judicious with the amount of detail one gives in order to not disadvantage oneself in a situation or to be prudent/diplomatic. Now it stands in for bold-faced lies (often delivered with the pretence of irony) or mis/disinformation.

Definitions

John Stuart Mill argued that truth is what is left after public debate (Moloney & McGrath, 2020, p. 54)

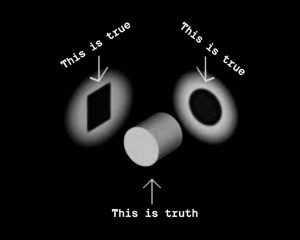

Truth as a matter of perspective:

History

Truth, today, doesn’t look like it once did. Stephen Colbert coined the term ‘truthiness’ to give a sense of this epistemic shift. He “coined the phrase in 2005 and used it to denote the trend of statements being made and accepted on the basis of how truthful they felt rather than any basis in evidence, logic, intellectual examination or fact” (Thompson, 2020, p. 87).

Truthiness summarizes the gravitational pull of ‘factual relativism’ and the shift to an affective underpinning rather than the cognitive foundation upon which truth has historically relied.

Truthiness relevancy

According to Glenda Eoyang, the truth can exist in four different forms:

- subjective

- normative

- objective

- complex

Simply put, the truth is not an absolute no matter how it is framed. There are always personal biases or agenda, ideologies or ideas being expressed or explored. Understanding these different truths can allow smoother communication in a society or smaller groups. The subjective truth is rooted in one’s perspective, their feelings, or their opinions (the truth is subjected to the way the individual feels). This means that it what is said is true for the individual, as they believe it. The opposite of subjective truth is normative truth. While a subjective truth relates to the individual, normative truth is what a collection of people agree to be truthful. It is widely accepted as being true, and therefore “must” be true. The objective truth considered to be definitive truth, as it is what can be visibly proved in the physical world. We know something is “objectively true” when we watch it happen (we know a lion is a predator because we’ve seen it hunt and consume other animals). This form of truth is held with the highest regard compared to subjective or normative truth, and it is associated with fields of study such as science or math. Finally, the complex truth is the idea that subjective, normative and objective truth are all valid forms of the truth. In essence, it allows people to rely on whichever form of truth best suits their needs in any given moment. According to the complex truth, all forms of the truth are valid and there is no singular way to think of the truth.

https://www.hsdinstitute.org/resources/four-truths.html / https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_CgBfLwLMWU&list=PL16mxHkvzi6WE-63MkzjULwVxu8c-SlDk

Gist truth

“People have a more-nuanced view of misinformation than the binary distinction between ‘fake news’ and ‘real news’ implies. We distinguish between the truth of a statement’s verbatim details (i.e., the specific, literal information) and its gist (i.e., the general, overarching meaning), and suggest that people tolerate and intentionally spread misinformation in part because they believe its gist. That is, even when they recognize a claim as literally false, they may judge it as morally acceptable to spread because they believe it is true ‘in spirit’” (Langdon et al., 2024, p. 1). Belief in the gist of things (turning blatant falsehoods into truthy falsehoods) increases based on prior knowledge, imagination, and partisanship (when false claims are consistent with participants’ prior knowledge, when people imagine how falsehoods could have been or might become true, and when falsehoods are told by a political ingroup) (Langdon et al., 2024, p. 3). Thus, even when people know misinformation is false, it can be excused when it communicates a ‘truthful gist’.

Context & Connections

Setting the stage for post-truth, we can understand that we are in a moment of epistemic uncertainty and factual relativism, a prioritizing of worldview over facts that has been termed “truth decay.” This is a way of describing “the growing climate of distrust that includes an increasing tendency to rely on personal beliefs over evidence to judge whether information is true. Truth decay encompasses an increase in disagreements about facts, the blurring of lines between opinions and facts in journalism, the increasing volume and influence of opinion and personal experience over fact, and a deterioration of trust in sources of information that were formerly respected” (Stebbins, 2023, p. 34). Like many other related topics, this issue of truth decay (admittedly, ‘truthiness’ cast in a negative light) is connected to the prolific nature of social media. “While there has always been a tension between believing in facts versus being influenced by worldviews, social media platforms are now exacerbating this shift by cueing fast, emotion-based thinking and promoting sensationalized and low-credibility content” (Stebbins, 2023, p. 62).

There is a widespread sense of crisis fuelled by fundamental shifts in our media and communication landscape. It’s commonplace to encounter stories based in a crisis of belief (what to believe), crisis of authority (who to believe), or even crisis of faith (whether we can believe). Together, these might be termed a “crisis of truth” whereby “certainties have increasingly become questionable in a time of falsified images and videos, hired trolls, secret service activities, forged profiles, social bots and perfectly orchestrated propaganda.” This world no longer depends upon “more hierarchically structured knowledge and media … shaped by comparatively powerful gatekeepers and a certain stability of materials and documents, and thereby implicitly supported classical concepts of truth” (Poerksen, 2022, p. 9). In a world where everything is epistemologically uncertain, we can’t look to truth as an arbiter of common sense or an anchor of objectivity. With such a pervasive sense of crisis where truth is under threat and trust is also withdrawn from traditional sources of authority, “truth is lost in a black hole of human experience, ever present but unable to be seen in a collapsing informational field of dark matter” (Macnamara, 2020, p. 131). This sounds bad (d’uh).

In this environment, truth isn’t something equally accessible to all (or agreed upon by all). It becomes partial, partisan, and polarizing. “Some have even argued that truth itself has been weaponised” (Morris, 2021, p. 320). And this is where we pick up the narrative thread as we look ahead and shift our focus to “post-truth” …

References

Franfurt, H. (2018). On truth. Alfred A. Knopf.

Hameleers, M., & Yekta, N. (2023). Entering an Information Era of Parallel Truths? A Qualitative Analysis of Legitimizing

and De-legitimizing Truth Claims in Established Versus Alternative Media Outlets. Communication Research, 1–23.

Langdon, J. A., Helgason, B. A., Qiub, J., & Effron, D. A. (2024). “It’s Not Literally True, But You Get the Gist:” How nuanced understandings of truth encourage people to condone and spread misinformation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 57, 1-6.

Macnamara, J. (2020). Beyond Post-Communication: Challenging disinformation, deception, and manipulation. Peter Lang.

Moloney, K., & McGrath, C. (2020). Rethinking Public Relations: Persuasion, Democracy and Society (3rd edition). Routledge.

Morris, J. (2021). Simulacra in the Age of Social Media: Baudrillard as the Prophet of Fake News. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 45(4) 319–336.

O’Hara, I. (2022). Automated Epistemology: Bots, Computational Propaganda & Information Literacy Instruction. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 48, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102540

Poerksen, P. (2022). Digital Fever: Taming the Big Business of Disinformation. Palgrave macmillan.

Stebbins, L. F. (2023). Building Back Truth in an Age of Misinformation. Rowman & Littlefield.

Thompson, G. (2020). Post-Truth Public Relations: Communication in an Era of Digital Disinformation. Routledge.

Zoglauer, T. (2023). Constructed Truths: Truth and knowledge in a post-truth world. Springer Vieweg.

Feedback/Errata