Conspiracy theories: The language of extreme belief

What are Conspiracy Theories?

Introduction

The link between the previous unit (fake news) and conspiracy theories is obvious: “Fake news and conspiracy theories are born and diffuse rapidly in times of heightened uncertainty, when high quality information is difficult to access, when trust in available sources of information is low… and when uncertainty, anxiety, threat, or fear are high” (Spitzberg, 2021, p. 15). Conspiracy thinking fit in with a wider social milieu of bullshit, and thus relates to similar concerns that should, by now, seem familiar:

Variably, conspiracy theory is described as being caused by the loss of postwar economic and geo-political stability, information overload and the concomitant loss in intellectual authority and expertise that allow people to sort the quality and veracity of truth claims based on that information, the loss of individual agency and a resulting agency panic, the crisis of life lived under the constant surveillance undertaken by the state and by corporate interests, and the ongoing identity crisis and cultural paranoia that are the result of postmodernity and late capitalism. (Fenster, 2008, p. 18)

“All conspiracy theories have something in common: they are characterized by persistent beliefs about secret and powerful forces which are operating behind the scenes to implement some sinister agenda.” (van der Linden, 2023, p. 49). But there is an argument that these are not theories at all but rather forms of (highly) motivated reasoning. Our basic cognitive processes (memory, perception, attention, judgement) are coloured by our own motivations. “The motivated brain selectively and often consciously seeks out or rejects evidence in a way that supports what you already believe” (van Der Linden, 2023, p. 33). Our brains, essentially, fill in gaps where we don’t know things with what we would like to be true. And, especially in a world of information overload, we don’t always expend mental resources to find the truth, to know one has the most accurate sources of evidence as much as we expend resources determining what information to select and process; In conditions of stress, we take shortcuts, and constantly bombarded with information, we are more likely to process information that we are motivated to consume” (van Der Linden, 2023, p. 34).

Definitions

“Conspiracy theories are essentially sensationalistic and unverified claims that take the form of a counter-narrative that questions “official” understandings of some event” (Neville-Shepard & Whiteside, 2024, p. 3).

“We conceptualize conspiracy theories to be those allegations that a group of individuals is working in secret for their own gain; the difference between a conspiracy and a conspiracy theory is that the latter may or may not be true” (Rhodes-Purdy et al., 2023, p. 216). This is interesting insofar as it admits that conspiracies are real, of course, even if society’s need to posit them where they might not exist means we can also classify conspiracy theories as “fictional narratives with a paranoid streak” (Cosentino, 2020, p. 67). One can choose to emphasize the fictional or the paranoid element here. Those who choose the former find themselves getting potentially lost in a game of ascertaining proof because “a conspiracy theory is typically a narrative of a possible past constructed with the material of a large amount of facts that have really happened and that are commonly accepted as ‘real’ and other fictitious, or at least not proven and not commonly accepted, elements which are supposed to have happened” (Zwierlein cited by Thalmann, 2019, p. 3). Those who go the latter route see the lunatic fringe elements of society engrossed in a “paranoid style” of reasoning and the image of a vast and sinister conspiracy, a gigantic and yet subtle machinery of influence set in motion to undermine and destroy a way of life (see Hofstadter, 1966).

Focusing on paranoid style suggests that “conspiracy theory constitutes a malady or affliction that differs fundamentally from a healthy engagement in politics and surfaces in trivial and groundless claims made by marginal groups” (Fenster, 2008, p. 8).[1] This perspective, however, misses out on the realization that, for many, especially the disenfranchised or disempowered, conspiracy theories can function as gratifying, aspirational emancipatory counternarratives. One could even say that “conspiracy theories are necessary to the healthy functioning of a society because they help balance against concentrations of power” (Uscisnki, 2017, p. 2). This is similar to Fenster’s assertion that, “too frequently, commentators glibly dismiss conspiracy theory as marginal and pathological, a dismissal that flattens its complexity and misunderstands its role in contemporary politics and culture” (2008, p. ix). His statement that “Conspiracy is not a ‘theory’ – in fact, it is everywhere” (2008, p. 7) is borne out in everyday examples: For instance, one can visit the Conspiracy Brewery in Ottawa[2] or go on the Lee Harvey Oswald and the JFK Conspiracy Tour in New Orleans[3].

We might be able to understand conspiracy theories by identifying their common structure. Following van der Linden’s suggestion, we can use the acronym CONSPIRE to guide us in our inquiry. Look for information defined by the following characteristics: Contradictory, Overriding suspicion, Nefarious intent, Something must be wrong, Persecuted victim, Immune to evidence, and Re-interpreting randomness Even though claims may seem outlandish to those who aren’t so affected by them, “what all [conspiracy] theories have in common is that they use a grain of truth, a real event – something people care about – in order to gain mainstream traction and appeal” (van der Linden, 2023, 204). Conspiracy theories are tied together by a cynical worldview defined by social and political distrust.

Characterizing Conspiracy Theories

During the ongoing discussion over conspiracy theories, educators and researchers have always struggled to put a singular definition of what exactly defines a conspiracy theory. Three techniques have been identified by Hellinger (2019) to organize and make sense of such definitions. The first is, narrowing the meaning, attempts to tighten the definition. For instance, seeing conspiracy theories as a, “subset of false beliefs in which the ultimate cause of an event is believed to be due to a plot by multiple actors working together with a clear goal in mind, often unlawfully and in secret” (Hellinger, 2019). In the same way, Karen Douglas and Robbie Sutton describe conspiracy theories as being different from standard or accepted answers. They call them “fanciful alternatives” that are different from the normal ways of thinking about what happened (Hellinger, 2019). The narrowing approach provides valuable tools for understanding the psychological underpinnings of conspiracy beliefs, but it also invites ongoing reflection on the criteria used to define and evaluate these theories. Second, expanding the meaning. This is the flip side of the ‘narrowing’ coin. This perspective has philosophers expanding the definition of conspiracy theory to incorporate any reasonable thought towards the conspiracy. Although this point of view supports a broader understanding that is in line with the roots of the words “conspiracy” and “theory,” it could include explanations that involve secret operations, secret partnerships, and plans that affect how events play out. Lee Basham argues, “any explanation of events that includes a conspiracy as a salient cause” should be classified as a “conspiracy theory” (Hellinger, 2019). Third, reflecting Ordinary Usage. This is thought to be the most practical approach, motivated by a desire to get to the heart of what most people mean when they use the term “conspiracy theory,” while also recognizing that this idea is based on facts and may change in different societies and times. It prevents the public from getting put off by interpretations that are overly scientific or broad and may not correspond to what they believe a conspiracy theory is. In addition, using a meaning that fits with how things are usually used makes it easier to talk about the topic, both in public and in academic settings. [DJ]

Development of conspiracy theories (Social media)

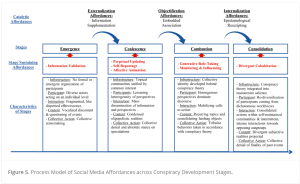

When there are new conspiracy theories that come about through the use of social media, it has been observed that they generally go through the same pipeline of events in order to become larger more mainstream beliefs that people get behind (Le et al., 2023). These are basically psychological stages that take place in peoples mind as well as throughout a large community at large in order to gain traction as a conspiracy theory.

This table essentially shows the 4 steps that people and populations take in order to form some kind of belief in conspiracy theories. It starts with the idea of emergence, where the idea comes from and where select individuals may choose to believe something, and then leads to coalescence, where a group of people may take the idea and apply it to a form of belief they possess. From this, the combustion stage leads to larger groups where the idea becomes more influential and forms a type of infrastructure of people that back the belief with ideologies that they think can supports the claims. Once all these steps have occurred, the consolidation step comes in and the conspiracy theory becomes populated into mainstream and social media, meaning that a large enough portion of the population have taken to the belief and backed it in some form. [NB]

History

“Although conspiracy theories may seem to be uniquely modern, they have existed throughout human history, some for hundreds of years, as in speculation about Jewish control over Christian culture” (Marwick & Partin, 2022, p. 3). Similarly, narratives about “the secret societies of Templars, Rosicrucians, Illuminati, and Freemasons have been circulating in Western societies at least since the crusades in the early Middle Ages. … Although such theories about an ‘exotic Other’ still exist, some scholars argue that conspiracy theories are nowadays increasingly about our ‘own’ modern societies, its institutions, and agents. … Contemporary conspiracy theories address the “enemy within” … the secret and malicious forces that lurk beyond the surface of modern society and operate within the institutions of politics, the medical industry, multinationals, and the laboratories of scientists” (Harambam & Aupers, 2015, p. 467). The barbarian might no longer be at the gates, because the barbarian lives among us.

While the Internet makes it easier than ever before to be exposed to conspiratorial thinking (and indeed, to believe in it, with the ability to retreat into echo chambers of self-confirming information), the popularization of conspiracy thinking can be traced back further in time. Thalmann posits that “a veritable conspiracist subculture emerged in the 1970s as conspiracy theories were pushed out of the legitimate marketplace of ideas and conspiracy theory became a commodity not unlike pornography: alluring in its illegitimacy, commonsensical, and highly profitable” (2019, p. iii). Subsequently, the serialization of conspiracy theories in the 1990s on TV in shows such as The X-Files mainstreamed conspiracy culture and ushered in an era of conspiracy theory as mass entertainment.[4] These built upon “conspiracy narratives [that] were uncommon in the first half of the twentieth century since studios and production companies preferred entertainment that would not be challenged by government censors but the Red Scare made it easier to talk about government infiltrators and grand plots to undermine the American way of life” (Neville-Shepard & Whiteside, 2024, p. 4).

Varieties

There are so many different types of conspiracies – some related to politics, some to celebrities, some to aliens. Some are taken more seriously than others…

What is particularly interesting is the fact that “the conspiratorial worldview is not characterized by belief in a single conspiracy. It’s what we call a ‘monological belief system‘, where belief in one conspiracy serves as evidence for another” (van der Linden, 2023, p. 49). So, someone who believes that Taylor Swift has been conscripted into a secret plot to help President Joe Biden get reelected in 2024 are also more likely to believe that there is a ‘deep state’ working to undermine Trump, etc.

Rather than examine different varieties of conspiracy theories, it might be useful to highlight how they fulfill at least three varieties of basic psychological needs: The first function of conspiracies is epistemological – they satisfy the desire to make sense of the world. They offer simple causal explanations for what might otherwise seem chaotic or random. They help people feel as though they’re in the know, that they aren’t one of those sad-sack others who follow blindly.

The second function of conspiracies is to offer existential relief. Conspiracy theories offer straightforward answers to complicated questions about our existence. They give people a sense of agency and control over their uncertain realities.

Lastly, conspiracy theories serve basic relational needs. They give people who feel marginalized in society an opportunity to affiliate and belong to a community with a common cause (van der Linden, 2023, p. 51).

Context & Connections

Fenster believes that far from being dangerous or ‘pathologically marginal’, “the prevalence of conspiracy theories is neither necessarily pernicious nor external to American politics and culture but instead an integral aspect of American, and perhaps modern and postmodern, life” (2008, p. 9).[6] Engaging in conspiracy thinking is, in fact, so widespread [stats] that it seems reasonable to suggest that the phenomenon says something about what people think matters and what is meaningful in contemporary political and cultural life. As van der Linden points out, “conspiracy theories have gone mainstream” (2023 203). The point isn’t to determine its causes as to investigate this language use as a source of interpretation and widely spread and socially endorsed narratives.

References

Fenster, M. (2008). Conspiracy theories: Secrecy and power in American culture. 2nd edn. University of Minnesota Press.

Harambam, J., & Aupers, S. (2015). Contesting epistemic authority: Conspiracy theories on the boundaries of science. Public Understanding of Science, 24(4) 466–480. DOI: 10.1177/0963662514559891

Hellinger, D. C. (2019). Conspiracies and conspiracy theories in the age of trump. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98158-1

Hofstadter, R. (1966). The Paranoid Style in American Politics. Alfred A. Knopf.

Marwick, A. E., & Partin, W. C. (2022). Constructing alternative facts: Populist expertise and the QAnon conspiracy. new media & society, 1–21.

Neville-Shepard, R., & Whiteside, A. (2024). Kinder-Conspiracy Theories: Disney’s Gravity Falls and the Conspiracy Genre in Children’s Television. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 1–17. DOI: 10.1177/01968599231223187

Rhodes-Purdy, M., Navarre, R., & Utych, S. (2023). The Age of Discontent: Populism, Extremism, and Conspiracy Theories in Contemporary Democracies. Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, J. (2023). Everything’s Connected: Conspiracy, Critique, and Articulation. In Media Res: Critique and the Moving Image II. https://mediacommons.org/imr/content/everything%E2%80%99s-connected-conspiracy-critique-and-articulation

Spitzberg, B. H. (2021). Comprehending Covidiocy Communication: Dismisinformation, Conspiracy Theory, and Fake News. In H. D. O’Hair & M. J. O’Hair (Eds.), Communicating Science in Times of Crisis (pp. 15-53). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Thalmann, K. (2019). The Stigmatization of Conspiracy Theory since the 1950s: “A Plot to Make us Look Foolish.” Routledge.

Uscisnki, J. (2017). The study of conspiracy theories. Argumenta. https://www.argumenta.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/3-Argumenta-Joseph-Uscinski-The-Study-of-Conspiracy-Theories.pdf

van der Linden, S. (2023). Foolproof: Why misinformation infects our minds and how to build immunity. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Also, the links to a Frankfurtesque notion of bullshit are explicit. Quoting Hofstadter, Fenster notes how style is above all, a way of seeing the world and of expressing oneself that is concerned with the way in which ideas are believed and advocated rather than with the truth or falsity of their content (2008, p. 32). ↵

- Some of their beer selections include Area51, Cousin Yeti, Chemtrails, New World Order, and the Grassy Knoll. See their evocative language and imagery at https://ctbrewing.ca. ↵

- see https://nolaadventures.com/adventures/lee-harvey-oswald-and-the-jfk-conspiracy-tour/ not to mention the variety of options available if you're visiting the site of President Kennedy's assassination in Dallas. ↵

- Viewed 'creatively', the recent zenith of box office success, "the Marvel Cinematic Universe, essentially presents a grandiose conspiracy narrative about how seemingly independent security crises are not only interconnected but organized by a shadowy figure seeking ultimate biopolitical power" (Roberts, 2023). ↵

- https://www.reddit.com/r/conspiracytheories/comments/jfbdf3/i_really_couldnt_care_less_if_the_earth_is_flat/ ↵

- Tellingly, the introduction to Fenster's book is subtitled "We're all conspiracy theorists now." ↵

Feedback/Errata