Information

7 What is information?

Introduction

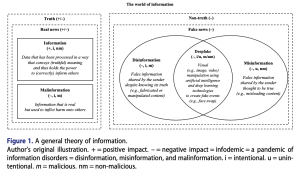

“The role of information – whether through education, exposure, content availability – has been taken, normatively, as a linchpin of a democratic society. … [It is assumed that] better and more information produces better individual and, in turn, collective decisions” (Loveless, 2020, p. 64). It is widely assumed that information is the foundation for thoughtful, purposeful action. But why must we have a section detailing information before we get to the ‘good stuff’ (read ‘actually really bad stuff which is good and necessary to pay attention to’) that occupies our cultural imagination (stuff like misinformation and disinformation, not to mention fake news, post-truth, etc)? Information seems so ‘basic’ and obviously understood, after all. The answer, though, lies in the conundrum that all of these other concepts depend upon an understanding (and a distortion) of information. As Morris points out, the normative expectations about the civic information process (whereby we learn about the social and political world, exchange information and opinions with fellow citizens and make reasoned judgements about public affairs) does not describe the actual reality when citizens engage with news via social media (2021, p. 321). Indeed, all of the pressing issues of the day (like fake news, conspiracy theories, propaganda, etc) are forms of problematic information, understood as “inaccurate, misleading, inappropriately attributed, or altogether fabricated information” (Jack, 2017, p. 2). Taken together as a constellation of concerns, it might be said that we live in an “ongoing crisis of problematic information” (Di Domenico & Visentin, 2020, p. 409).[1] Though there are many ways to make sense of this, some suggest that we live in a state of “information disorder [which] eludes precise definition or dichotomous distinction between what is true and what is false but includes nuanced forms of objective news, disseminated together with unverified or verifiable data, news that is only verisimilar or what is commonly referred to as conspiracy theories” (Monachi, 2023, p. 1). If a normal diet of information is orderly, we live disordered lives when it comes to information, subject to so much bullshit as to make judgments about good and bad, right and wrong, true and false, anything but easy or straightforward. The complexity of all of this can be seen in the following diagram, Lim’s (2020, p. 2) graphic depiction of how the category of information subsumes a wide variety of both truthful and non-truthful claims:

Definitions

The term Information Overload and its understanding started more within the computer science and information science fields, but has grown considerably over the past few years. The shift towards an information-based economy and away from an industrial economy prompted growth of research for this term. While there is no ‘set’ or agreed upon definition, Information overload is usefully contextualized as, “The result of so much useful and relevant information that it hinders rather than helps” (Bawden and Robinson, cited in Belabbes, et. al. 2023). The first proper definition was coined by Gross in 1965, stating that information overload “highlights the limited cognition of humans i.e. when they become overloaded with information, their decision making suffers” (Belabbes, et. al. 2023).

Information overload used to be understood as caused by poor recall and precision of search engines/ lack of effective algorithms, but with the changes to our digital sphere the causes have shifted. The causes are now believed to come from lack of information literacy, doubled information, nonsense/ fluff information, poor quantity or quality of information, complexity/ lack of prior knowledge or lack of time. All these factors are believed to generate information overload in our modern day digital world. [BC – see quote below]

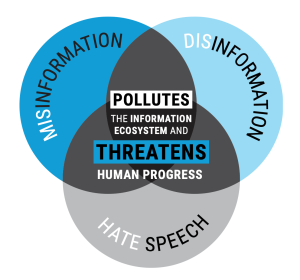

Linked to the issue of information overload is the concern about information pollution. Because of distortions of (positive or true) information (the concern of subsequent sections of this book), some believe our society is in danger (see the diagram, below (Guterres, 2023, p.5), sketching the contours of the situation):

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the issue of misinformation being spread across social media/ online information spheres rose significantly. During the pandemic, we experienced this specifically surrounding health misinformation. The conflict between the need for reliable, true information and the business model of multi-sided platforms became much more relevant. (Haider, et al, 2022, p. 41). This created an “explosion of references to an ‘infodemic’, metaphorically likening the spreading of misinformation to the spreading of a virus” (Haider, et al, 2022, p. 41). In similar terms, Infodemic is comparing the spread of misinformation to the spread of a virus (like COVID-19), resulting in a flood of information that is unreliable. This was very prevalent during the pandemic, to the point that Google, YouTube, Twitter and other online information platforms created warnings or policies to combat this spread of infodemic. The general premise of these warnings and policies surrounded around the information given by WHO’s (World Health Organizations) medical information about COVID-19. Indicating that WHO’s information was the reliable or ‘true’ information, and anything else different was just bullshit or misinformation. (Haider, et all, 2022, p. 41-42) [BC- see quote below]

Infodemic in times of virus’s:

The term infodemic has been coined to outline the perils of misinformation phenomena during the management of disease outbreaks, since it could even speed up the epidemic process by influencing and fragmenting social response.

Responsibilisation

Before we lived in a technologically driven information society, information used to be gathered from places of knowledge such as the library. The library is responsible for facilitating information literacy through a credible and diverse inclusion of books and information for people to read and learn from while protecting community members from harmful content (Haider and Sundin, 2022, p.26). When going to a library, it is assumed that the information is reliable because of the vetting process the library goes through to select the content. The library will “consult book reviews, recommended reading lists from reliable sources, book awards, bestseller lists and suggestions from community members” (Chamberlain, 2019), with the goal of sourcing high-quality information that meets the community’s needs and expands their knowledge and perspectives (Chamberlain, 2019). The inherent trust in the library and its ability to properly assess and provide information is something that is foreign to the internet’s relationship with information. The internet is unfiltered and vast. The rapid growth, increased access to, and surplus of search engines and social media has changed the nature of information. Now, there is too much information (as described in the definition of information overload above). The era of information overload and technology lacks the filtration systems that libraries have in place to ensure responsible distribution and access to information. Instead, responsibility has been shifted from the institution to the user, placing the onus on the user to educate themselves in the pursuit of risk privatization (Juhila et al., 2017, p.7).

This transfer of responsibility from an institution to the individual can be described as Responsibilisation. Responsibilisation is when citizens are now responsible for something that a public institution was previously responsible for (Haider and Sundin, 2022, p.26). “Citizen responsibilisation is thus linked to the retreat and “irreseponsibilization” of state and public government” (Juhila et al., 2017, p.7). This concept can be a disservice to the individual person when the intent is for the public institution to dispose of their responsibility, often in times of rapid and high-pressure change where the road ahead is difficult and in a state of constant change (Greenfield, 2009). It becomes the goal for institutions to promote the need for self surveillance and responsibility in the context of the societal rules to encourage and maintain a sense of hegemony while thrusting responsibility outside of their domain (Haider and Sundin, 2022, p.26). This can be conceptualized by understanding the difference between media literacy for online content consumption and libraries. As mentioned, libraries assume the responsibility of ensuring quality and productive content is placed on the shelves (Chamberlain, 2019). As the internet developed, it became THE substitute for libraries. But did the internet have staff that filtered through the content to ensure it was quality and productive? No! That is because, with an innovation like the internet, it is a new black box of mystery. In a neo-liberal context, it is easier to let the internet simply playout and divert the responsibility of informational intake and production to the user in exchange for economic prosperity for the institutions and businesses involved. Responsibilisation is a term relevant to the neo-liberal context as the results of responsibilisation often leads to connections within capitalism and corporate growth, “consider how the governing of the self also extends to internalisation of corporate rules, algorithmic decisions, and the demands of the market.” (Haider and Sundin, 2022, p.27). Media literacy is the result of responsibilisation for the online informational world. Compared to libraries and their infrastructural filtration system that sifts through information for people, media literacy has become the education that is necessary so users can properly decipher the information they are consuming (Haider and Sundin, 2022, p.29) inside a tornado of “knowledge”. Based on this functional exploration of Responsibilisation, we should ask the question…is responsibilisation the foundation of the internet’s vastness of information?

References:

Chamberlain, J. (2019). How books are chosen for the Library | Library | Norfolkdailynews.com. https://norfolkdailynews.com/blogs/news/library/how-books-are-chosen-for-the-library/article_abd39334-3d35-11ea-be83-8f81f18f10e5.html

Greenfield, A. (2009, September 23). “responsibilization” and user experience. Adam Greenfield’s Speedbird. https://speedbird.wordpress.com/2009/09/22/responsibilization-and-user-experience/

Haider, J., & Sundin, O. (2022). Responsibility and the crisis of information. Paradoxes of Media and Information Literacy, 25–50. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003163237-2

Juhila, K., Raitakari, S., & Löfstrand, C. H. (2017). Responsibilisation in Govermentality Literature. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315681757

[CZ]

History

once upon a time …

Varieties

Typically, there are lots of different forms of our objects of inquiry … here is where we start to distinguish them…

The Information Society

The Information Society designates a specific division of developments which arise from the rapid increase of communication technologies and information (Mansell, 2009). The mid 1990s are often cited as an important period in which the quick growth of the internet allowed for research on the Information Society to expand. Mansell emphasizes some of the dangers of information technology, stating how “electronic information should not be straightforwardly associated with enhanced human well-being (2009, p. 2). It becomes clear how these information societies begin to shape the social, economic, and political aspects of society, when the distribution, access, or manipulation of information is placed at such high value.

Mundie (2022) emphasizes the importance of having access to digital information in an increasingly technological and interconnected world. Many Canadians do not have proper access to digital technologies, and therefore lack access to various forms of information. Rural and Indigenous suffer the most due to a lack of infrastructure, in addition to low-income citizens who struggle to afford high internet and technology prices. Canadian libraries explain how they do not have the capacity to provide or teach skills of digital literacy to members of their communities. Canadians who lack this form of information literacy are left behind and miss many opportunities and pieces of knowledge which can only be found in something as complex as the internet. This is especially true in recent times; where the COVID-19 lockdowns had most people staying isolated in their home, many who did not have access to digital technologies suffered the most. As these information societies continue to grow, it is important to analyze who is excluded from these areas. When information is placed on such a high pedestal, it will eventually become harmful to certain demographics and communities. This access to information, or lack thereof, even has the power to shape cultural values and the ways in which people interact with society including their level of information literacy.

[RL]

Mansell, R. (2009). The information society. Routledge.

Mundie, J. (2022). Canadians lacking digital literacy left behind as world becomes more dependent on technology. National Post. https://nationalpost.com/feature/left-behind-digital-literacy

Type 2

One form of information, it must be noted, is untrue/harmful information (variously termed mis-information or dis-information). Macnamara argues that the latter term is a euphemism/buzzword that normalizes and trivializes what it really is – a form of “informational terrorism” (2020, p. 37).

…

Context & Connections

The degree of confidence we have in our information is directly related to the suggestion that we live in a post-truth society: “The fear of post-factual times and the current fake news panic are consequently symptoms of a more general feeling of insecurity with regard to information, a fear that all connections with reality may go up in smoke” (Poerksen, 2022, pp. 9-10). Thus, a clear understanding of information and its importance is not just a pre-requisite for grappling with concepts such as misinformation and disinformation, it is also necessary to fully grasp the issues of fake news and post-truth and conspiracy theories and everything else that flows from a crumbling foundation of information security.

And as “food for thought”, consider how memes encapsulate and spread information. In the face of information overload, one potential coping mechanism is to condense information into an incredibly easy-to-digest format. Unfortunately, one of the consequences of this is that memes are a really obvious source of misinformation, but that’s the next unit…

So, having detailed some of what makes information

References

Belabbes, M. A., Ruthven, I., Moshfeghi, Y., & Diane, R. P. (2023). Information overload: a concept analysis. Journal of Documentation, 79(1), 144-159. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-06-2021-0118

Cinelli, M., Quattrociocchi, W., Galeazzi, A., Valensise, C. M., Brugnoli, E., Schmidt, A. L., Zola, P., Zollo, F., & Scala, A. (2020). The COVID-19 social media infodemic. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 16598. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5

Di Domenico, G., & Visentin, M. (2020). Fake news or true lies? Reflections about problematic contents in marketing. International Journal of Market Research 62(4), 409–417

Guterres, A. (2023). Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 8: Information Integrity on Digital Platforms. United Nations. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/our-common-agenda-policy-brief-information-integrity-en.pdf

Haider, Jutta, and Sundin, Olof. (2022). “Responsibility and the crisis of information” in Paradoxes of media and information literacy: the crisis of information (pp. 25-50).

Jack, C. (2017). Lexicon of lies: Terms for problematic information. Data and Society.

Lim, W. M. (2023). Fact or fake? The search for truth in an infodemic of disinformation, misinformation, and malinformation with deepfake and fake news. Journal of Strategic Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2023.2253805

Loveless, M. (2020). Information and democracy: Fake news as an emotional weapon. In S. Giusti & E. Piras (Eds.), Democracy and Fake News: Information Manipulation and Post-Truth Politics (pp. 64-76). Routledge.

Monaci, S. (2023). #dominant Voices in the New Disinformation Order in M. Filimowicz (Ed.), Information Disorder: Algorithms and Society (pp. 1-28). Routledge.

Morris, J. (2021). Simulacra in the Age of Social Media: Baudrillard as the Prophet of Fake News. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 45(4) 319–336.

Poerksen, P. (2022). Digital Fever: Taming the Big Business of Disinformation. Palgrave macmillan.

- This sensibility, to be honest, is kind of the rationale behind this entire course! ↵

Feedback/Errata