“Pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever the experiencing person says it does” (McCaffery, 1968, cited in Rosdahl & Kowalski, 2007, p. 704). Pain is a subjective experience, and self-report of pain is the most reliable indicator of a patient’s experience. Determining pain is an important component of a physical assessment, and pain is sometimes referred to as the “fifth vital sign.”

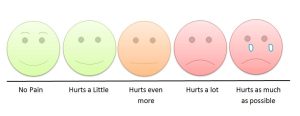

Pain assessment is an ongoing process rather than a single event (see Figure 2.1). A more comprehensive and focused assessment should be performed when someone’s pain changes notably from previous findings, because sudden changes may indicate an underlying pathological process (Jarvis, Browne, MacDonald-Jenkins, & Luctkar-Flude, 2014).

Always assess pain at the beginning of a physical health assessment to determine the patient’s comfort level and potential need for pain comfort measures. At any other time you think your patient is in pain, you can use the mnemonic LOTTAARP (location, onset, timing, type, associated symptoms, alleviating factors, radiation, precipitating event) to help you remember what questions to ask your patient. See Checklist 14 for the questions to ask and steps to take to assess pain.

Critical Thinking Exercises

- You are caring for a patient who has just returned from a surgical procedure. The patient has a history of chronic pain. Would the patient’s assessment provide the same data as an assessment of a person who does not have a history of chronic pain?

- What is more important: the subjective or the objective data in a pain assessment?

Attribution

Figure 2.1

Children’s pain scale by Robert Weis is used under a CC BY SA 4.0 licence.