7 Physical Development in Middle Childhood

Chapter Objectives

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the patterns of physical growth

- Summarize nutrition needs

- Explain the causes of obesity and the negative consequences of excessive weight gain

- Explain challenges to physical health including, vision, hearing, oral health, diabetes, asthma and childhood stress

INTRODUCTION

Children in middle childhood go through tremendous changes in the growth and development of their brain. During this period of development children’s bodies are not only growing, but they are becoming more coordinated and physically capable. Children are more mindful of their greater abilities in school and are becoming more responsible for their health and diet.

brain development

The brain reaches its adult size at about age 7. Then between 10 and 12 years of age, the frontal lobes become more developed and improvements in logic, planning, and memory are evident (van der Molen & Molenaar, 1994, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). The school-aged child is better able to plan and coordinate activity using both the left and right hemispheres of the brain, which control the development of emotions, physical abilities, and intellectual capabilities. The attention span also improves as the prefrontal cortex matures. The myelin also continues to develop and the child’s reaction time improves as well. Myelination improvement is one factor responsible for these growths.

From age 6 to 12, the nerve cells in the association areas of the brain, that is those areas where sensory, motor, and intellectual functioning connect, become almost completely myelinated (Johnson, 2005, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). This myelination contributes to increases in information processing speed and the child’s reaction time. The hippocampus, which is responsible for transferring information from the short-term to long-term memory, also shows increases in myelination resulting in improvements in memory functioning (Rolls, 2000, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Figure 14.1: The human brain. (Image by DJ is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0)

physical growth

Middle childhood spans the years between early childhood and adolescence, children are approximately 6 to 12 years old. While growth spurts can happen, in general physical growth rates are generally slow and steady during these years. (Spreen, Riser, & Edgell, 1995, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Typically, a child will gain about 5-7 pounds a year and grow about 2 inches per year. They also tend to slim down and gain muscle strength. As bones lengthen and broaden and muscles strengthen, many children want to engage in strenuous physical activity and can participate for longer periods of time. In addition, the rate of growth for the extremities is faster than for the trunk, which results in more adult-like proportions. Long-bone growth stretches muscles and ligaments, which results in many children experiencing growing pains, at night, in particular.

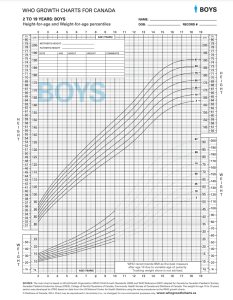

Figure 14.2: Dieticians of Canada (2014a)

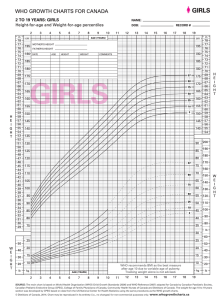

Figure 14.3: Dieticians of Canada (2014b).

As you can see from the above charts, there is a similarity in the average heights and weights of boys and girls during this developmental stage. For instance, at the age of 6 boys in the 50th percentile weigh 47 pounds and are 45.5 inches tall and girls measure in at 46 pounds and 45 inches tall. At the age of 9, boys in the 50th percentile weigh 52 pounds and are 62 inches tall and girls measure at the same. It also should be noted here that the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends Body Mass Index (BMI) as the best measure of weight after age 10, due to variable age of puberty and tracking weight alone is not advised (Dieticians of Canada, 2014b). According to the Childhood Obesity Foundation (n.d.), BMI is an indirect indicator of body fat. It is a measurement based on height and weight that tells if a child, or adult, is in a healthy range compared to their peers. It should be noted that BMI may not be an accurate indicator of body fat if your child is very muscular. There are lots of online tools available to calculate BMI in children. Check out these Smart BMI Calculators.

Beyond height and weight, a child’s physical growth can be seen in other ways. Children between ages 6 and 12, show significant improvement in their abilities to perform physical motor skills. This development growth allows children to gain greater control over the movement of their bodies, mastering many gross motor skills that were beyond that of the younger child. The Continuum of Development shares that during these middle childhood years, the development of gross motor skills continues to focus on increasing coordination, speed, and endurance (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014).

Specifically, the gross motor skills that we see strengthen most, in children aged 6-12, are:

- Running: increasing control, speed and coordination;

- Jumping: jumping vertically increases in height, standing broad jump increases in length;

- Throwing: throwing speed, distance and accuracy improve;

- Catching: catching small balls over greater distances;

- Kicking: kicking speed and accuracy improve (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014).

nutritional needs

A number of factors can influence children’s eating habits and attitudes toward food. Family environment, societal trends, taste preferences, and messages in the media all impact the emotions that children develop in relation to their diet. Television commercials can entice children to consume sugary products, fatty fast foods, excess calories, refined ingredients, and sodium. Therefore, it is critical that caregivers support children with making healthy nutritional choices by reinforcing good eating habits and by introducing new foods into the diet, while remaining mindful of a child’s preferences. Caregivers should also serve as role models for children, who will often mimic their behaviour and eating habits. Let’s think for a moment about what our parents and grandparents used to eat? What are some of the differences that you may have experienced as a child?

One hundred years ago, as families sat down to dinner, they might have eaten boiled potatoes or corn, leafy vegetables such as cabbage or collards, fresh-baked bread, and, if they were fortunate, a small amount of beef or chicken. Young and old alike benefitted from a sound diet that packed a real nutritional punch. Times have changed. Many families today fill their dinner plates with fatty foods, such as French Fries cooked in vegetable oil, a hamburger that contains several ounces of ground beef, and a white-bread bun, with a single piece of lettuce and a slice or two of tomato as the only vegetables served with the meal.

Figure 14.4: A modern meal. ( Image is licensed under CCO)

Our diet has changed drastically as processed foods, which did not exist a century ago, and animal-based foods now account for a large percentage of our calories. Not only has what we eat changed, but the amount of it that we consume has greatly increased as well, as plates and portion sizes have grown much larger. All of these choices impact our health, with short- and long-term consequences as we age. Possible effects in the short-term include excess weight gain and constipation. The possible long-term effects, primarily related to obesity, include the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, as well as other health and emotional problems for children.

During middle childhood, a healthy diet facilitates physical, social/emotional and cognitive development and helps to maintain health and wellness. School-aged children experience steady, consistent growth, but at a slower rate than they did in early childhood. This slowed growth rate can have a lasting impact if nutritional, caloric, and activity levels aren’t adjusted in middle childhood which can lead to excessive weight gain early in life and can lead to obesity into adolescence and adulthood. Making sure that children have proper nutrients will allow for optimal growth and development.

Figure 14.5: Government of Canada (2020)

The Government of Canada (2020), via their Canada Food Guide, recommends that individuals over the age of six:

- Eat plenty of vegetables and fruits, whole grain foods and protein foods. Choose protein foods that come from plants more often.

- Choose foods with healthy fats instead of saturated fat

- Limit highly processed foods. If you choose these foods, eat them less often and in small amounts.

- Prepare meals and snacks using ingredients that have little to no added sodium, sugars or saturated fat

- Choose healthier menu options when eating out

- Make water your drink of choice

- Replace sugary drinks with water

- Use food labels

- Be aware of food marketing

Caregivers should teach children that healthy eating is more than the foods you eat. The Government of Canada (2020) recommends that we:

- Be mindful of eating habits (take time to eat; notice when full/hungry),

- Cook more often (plan what to eat; involve others in the preparation).

- Enjoy food

- Eat meals with others

One way to encourage children to eat healthy foods is to make meal and snack time fun and interesting. Parents should include children in food planning and preparation, for example selecting items while grocery shopping or helping to prepare part of a meal, such as making a salad. At this time, parents can also educate children about kitchen safety. It might be helpful to cut sandwiches, meats, or pancakes into small or interesting shapes. In addition, parents should offer nutritious desserts, such as fresh fruits, instead of calorie-laden cookies, cakes, salty snacks, and ice cream. Studies show that children who eat family meals on a frequent basis consume more nutritious foods.

energy

Children’s energy needs vary, depending on their growth and level of physical activity. Energy requirements also vary according to gender. Girls require 1,200 to 1,400 calories a day from age 2 to 8 and 1,400-1,800 for age 9 to 13. Boys also need 1,200 to 1,400 calories daily from age 4 to 8 but their daily caloric needs go up to 1,600-2,000 from age 9 to 13. This range represents individual differences, including how active the child is.

Recommended intakes of macronutrients (protein, carbohydrates, and fats) and most micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) are higher relative to body size, compared with nutrient needs during adulthood. Therefore, children should be provided nutrient-dense food at meal- and snack-time. However, it is important not to overfeed children, as this can lead to childhood obesity, which is discussed in the next section.

children and vegetarianism

Some parents and caregivers decide to raise their children as vegetarians for health, cultural, or other reasons. School aged children may make the choice to pursue vegetarianism on their own, due to concerns about animals or the environment. No matter the reason, with good planning, a vegetarian diet can be a healthy choice that meets a growing child’s nutritional needs.

type of vegetarian diets

There are several types of vegetarians, each with certain restrictions in terms of diet:

Ovo-vegetarians- eat eggs, but do not eat any other animal products.

Lacto-ovo-vegetarians- eat eggs and dairy products, but do not eat any meat.

Lacto-vegetarians- eat dairy products, but do not eat any other animal products.

Vegans- eat food only from plant sources, no animal products at all.

Figure 14.6: A school lunch (Image from Pixabay)

Children and malnutrition

Many may not know that malnutrition is a problem that many children face, in both developing nations and the developed world. Even with the wealth of food in North America, many children grow up malnourished, or even hungry. Household food insecurity is inadequate or insecure access to food because of income or finances. It is a serious public health issue in Canada that negatively impacts physical, mental, and social health, and costs our healthcare system considerably (Dieticians of Canada, 2021). In 2017-2018, one in eight Canadian households was food insecure, amounting to 4.4 million people, including 1.2 million children (PROOF, 2021).

Growing up in a food-insecure environment can have significant consequences on a child’s healthy growth and development and well-being. According to Children First Canada (2020), food insecurity can affect children in the following ways:

- Obesity: Most caregivers ensure that their children are fed as much as possible, despite any financial setbacks, however these same parents may not have the money or time to prepare nutritious meals. This can lead to families eating a lot of cheap foods with low nutrition density.

- Nutritional and vitamin deficiencies: Children eating foods that are not nutrient-dense can end up with various nutritional deficiencies leading to fatigue or even illness. Anemia, stunted growth or bone deformities and abnormalities may occur. Additionally, children who are nutrient-deficient will also be moodier and face more challenges maintaining emotional stability, which hinders their ability to mature in this area.

- School challenges: Children who don’t get sufficient nutrition are going to be fatigued throughout the day and this can impact their educational performance. They may end up with poor grades, even if they’ve done all of the required work and studying. They may have a harder time making friends and forming bonds, stunting their emotional and social development.

- Parental stress: Adults who are dealing with food and financial insecurity are likely to be stressed, depressed or otherwise unwell. Over-stressed caregivers aren’t able to give as much time and attention to their children and even with the best intentions, they may end up emotionally blocked off. When the parents are stressed, so are the children.

- Generational poverty: Children who grow up in food-insecure homes can easily turn into adults who lead food-insecure homes. While many people aspire to do better than the households that they came from, it’s harder to move up in life when you have fewer resources available to you.

Indigenous Perspectives

The following article First Nations Nutrition discusses the risk of malnourishment and chronic diseases in First Nations children.

Being Overweight and Obesity in Children

Excess weight and obesity in children are associated with a variety of medical conditions including high blood pressure, insulin resistance, inflammation, depression, and lower academic achievement (Lu, 2016, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Being overweight has also been linked to impaired brain functioning, which includes deficits in executive functioning, working memory, mental flexibility, and decision making (Liang, Matheson, Kaye, & Boutelle, 2014, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Children who ate more saturated fats performed worse on relational memory tasks, while eating a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids promoted relational memory skills (Davidson, 2014, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Using animal studies, Davidson et al. (2013, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021) found that large amounts of processed sugars and saturated fat weakened the blood-brain barrier, especially in the hippocampus. This can make the brain more vulnerable to harmful substances that can impair its functioning. Another important executive functioning skill is controlling impulses and delaying gratification. Children who are overweight show less inhibitory control than normal-weight children, which may make it more difficult for them to avoid unhealthy foods (Lu, 2016, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Overall, being overweight as a child increases the risk for cognitive decline as one ages.

According to the Childhood Obesity Foundation (2019), it estimated that over 150 million children in the world are obese and this number is rising. In Canada specifically, the incidence of childhood obesity has nearly tripled in the last 30 years (Childhood Obesity Foundation, 2019), and one in four Canadian children are overweight or obese (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2016). Unfortunately, most adolescents do not outgrow this problem and in fact, many continue to gain excess weight. If current trends continue, by 2040 up to 70% of adults aged 40 years will be either overweight or obese worldwide (Childhood Obesity Foundation, 2019).

Obesity in childhood is associated with a wide range of serious health complications such as fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes. Obese children run the risk of suffering orthopedic problems such as knee injuries, and they have an increased risk of developing heart disease, type 2 diabetes, 13 different cancers, liver disease, hypertension and stroke in adulthood (Childhood Obesity Foundation, 2019). In addition, it is hard for a child who is obese to become a non-obese adult. Thus, this is a public health crisis that we need to tackle.

According to the Government of Canada (2019), the following are things that caregivers can do to support children at remaining in a healthy weight:

Eat healthy:

- Following the food guide,

- Set a good example by being a role model for healthy eating. Children are more likely to try new foods if their caregivers eat them too.

- Eat meals together as often as possible and make the food the focus. Turn off the TV and put away electronic devices during mealtime. Children often eat better without these distractions.

- Involve children in the planning and preparing of meals and snacks.

Be physically active:

- According to the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP), children and teenagers should participate in at least 60 minutes per day of moderate to vigorous physical activity involving a variety of aerobic activities. Vigorous physical activities, and muscle and bone strengthening activities should each be incorporated at least 3 days per week; Several hours of a variety of structured and unstructured light physical activities should also be incorporated into each child’s day (CSEP, 2021).

- Set a good example by being a role model for participating in healthy physical activity. Add physical activity to your daily routine and encourage children to join you.

- Limit the amount of time children spend on sedentary activities like watching television, playing video games, and surfing the web.

- Be aware of the opportunities your community offers to help your family stay healthy. Are there bike paths nearby? What community programs are available throughout the year?

Interestingly, behavioural interventions, including training children to overcome impulsive behaviour, are being researched to help overweight children (Lu, 2016, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Practicing inhibition has been shown to strengthen the ability to resist unhealthy foods. Caregivers can help their overweight/obese children the best when they are warm and supportive without using shame or guilt, helping them make correct food choices and praising their efforts (Liang, et al., 2014, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Increasing a child’s activity level is most helpful in combatting obesity and caregivers should be cautioned against emphasizing that diet alone will fix the problem. Dieting is not really the answer. When you diet, your basal metabolic rate tends to decrease thereby making the body burn even fewer calories in order to maintain the weight and often when one focuses on diet, it can lead to the development of an obsession about dieting. Obsessing about dieting often leads to the development of an eating disorder. Eating disorders are common in Canadian society, with up to 5% of young women having experienced an eating disorder before reaching adulthood. While anorexia nervosa typically has its onset in mid-adolescence, it can also occur in younger children (Findlay, Pinzon, Taddeo & Katzman, 2010).

Being Overweight Can Be a Lifelong Struggle

A growing concern regarding obesity is the lack of recognition from parents/caregivers that children are overweight or obese. Katz (2015) referred to this as “oblivobesity”. Black et al. (2015, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021) found that parents in the United Kingdom (UK) only recognized their children as obese when they were above the 99.7th percentile while the official cut-off for obesity is at the 85th percentile. Oude Luttikhuis, Stolk, and Sauer (2010, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021) surveyed 439 parents and found that 75% of parents of overweight children said the child had a normal weight and 50% of parents of obese children said the child had a normal weight. For these parents, overweight was considered normal and obesity was considered normal or a little heavy. Doolen, Alpert, and Miller (2009, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021) reported on several studies from the United Kingdom, Australia, Italy, and the United States, and in all locations, parents were more likely to misperceive their children’s weight. Black, Park, and Gregson (2015, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021) concluded that as the average weight of children rises, what parents consider normal also rises. If parents cannot identify if their children are overweight, they will not be able to intervene and assist their children with proper weight management.

Indigenous Perspectives

Indigenous people’s diets have been substantially changed by the coming of settlers. They brought the flour, salt, sugar, milk and lard. Those “5 white gifts” saved their lives but impacted their livelihood and their health. When the government put Indigenous people on reservations, they had to sign themselves out to go hunting, fishing and trapping. On some reservations, they were not allowed to go harvest. Some people starved and others learned to cook with them. The recipe for bannock or scone came from the Scottish people. These “staples” gave the Indigenous people diabetes and brought other sicknesses. The following link explains The White Gifts. Many remote communities don’t have fresh produce, food is very expensive, the produce that does make its way there is brown or discoloured; therefore, it is simpler and cheaper to eat foods that are not good for them. i.e. pasta, fried bread or bannock, processed foods, pop, chips, chocolate bars, etc). Obesity and diabetes are very prominent in these communities. As a result, diabetes initiatives have been put in place to try to curve the onset of diabetes, heart attacks and, strokes

Common Challenges with Physical Health

Vision and Hearing

The most common vision problem in middle childhood is being nearsighted, otherwise known as Myopic. 25% of children will be diagnosed by the end of middle childhood. Being nearsighted can be corrected by wearing glasses with corrective lenses.

Figure 14.7: A child receiving an eye exam. (Image is in the public domain)

Children may have many ear infections in early childhood, but it’s not as common within the 6-12 year age range. Numerous ear infections during middle childhood may lead to headaches and migraines, which may result in hearing loss.

Oral Health

Children in middle childhood will start or continue to lose teeth. They experience the loss of deciduous, or “baby,” teeth and the arrival of permanent teeth, which typically begins at age six or seven, although it can start as early as the age of 4. It is important for children to continue seeing a dentist twice a year to be sure that their teeth are healthy.

The foods and nutrients that children consume are also important for dental health. Offer healthy foods and snacks to children and when children do eat sugary or sticky foods, they should brush their teeth afterward.

Figure 14.8: A child brushing their teeth. (Image by Latrobebohs is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)

Children should floss daily and brush their teeth at least twice daily: in the morning, at bedtime, and preferably after meals. Parents or caregivers are encouraged to supervise brushing until your child is 7 or 8 years old to avoid tooth decay.

The best defence against tooth decay is flossing, brushing and adding fluoride; a mineral found in most tap water. If your water doesn’t have fluoride, ask a dentist about fluoride drops, gel or varnish. Also ask your child’s dentist about sealants—a simple, pain-free way to prevent tooth decay. These thin plastic coatings are painted on the chewing surfaces of permanent back teeth. They quickly harden to form a protective shield against germs and food. If a small cavity is accidentally covered by a sealant, the decay won’t spread because germs trapped inside are sealed off from their food supply.

Children’s dental health needs continuous monitoring as children lose teeth and new teeth come in. Many children have some malocclusion (when the way upper teeth aren’t correctly positioned slightly over the lower teeth, including under- and overbites) or malposition of their teeth, which can affect their ability to chew food, floss, and brush properly. Dentists may recommend that it’s time to see an orthodontist to maintain proper dental health. Dental health is exceedingly important as children grow more independent by making food choices and as they start to take over flossing and brushing. Parents can ease this transition by promoting healthy eating and proper dental hygiene.

In Ontario, children under the age of 17 years may be eligible for free dental care through the governments Healthy Smiles for low-income families (Government of Ontario, 2021).

Diabetes in Childhood

Until recently diabetes in children and adolescents was thought of almost exclusively as type 1, but that thinking has evolved. Type 1 diabetes is the most common form of diabetes in children and is the result of a lack or production of insulin due to an overactive immune system. Type 2 diabetes used to be referred to as adult-onset diabetes as it was not common during childhood. But with increasing rates of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents, more Type 2 diagnoses are happening before adulthood. It is also important to note that Type 2 disproportionately affects minority youth.

Figure 14.9: The finger-prick blood sugar test for diabetes. (Image by the U.S. Army is in the public domain)

Asthma

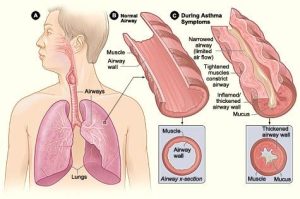

Childhood asthma that is unmanaged may make it difficult for children to develop to their fullest potential. Asthma is a chronic lung disease that inflames and narrows the airways. Asthma causes recurring periods of wheezing (a whistling sound when you breathe), chest tightness, shortness of breath, and coughing. The coughing often occurs at night or early in the morning. Asthma affects people of all ages, but it most often starts during childhood. According to Asthma Canada (n.d.), over 850,000 children under the age of 14 in Canada are affected by asthma. Asthma is the leading cause of school absences.

To understand asthma, it helps to know how the airways work. The airways are tubes that carry air into and out of your lungs. People who have asthma have inflamed airways. The inflammation makes the airways swollen and very sensitive. The airways tend to react strongly to certain inhaled substances. When the airways react, the muscles around them tighten. This narrows the airways, causing less air to flow into the lungs. The swelling also can worsen, making the airways even narrower. Cells in the airways might make more mucus than usual. Mucus is a sticky, thick liquid that can further narrow the airways. This chain reaction can result in asthma symptoms. Symptoms can happen each time the airways are inflamed.

Figure 14.10 : Figure A shows the location of the lungs and airways in the body. Figure B shows a cross-section of a normal airway. Figure C shows a cross-section of an airway during asthma symptoms. (Image by the National Hearth, Lung and Blood Institute is in the public domain)

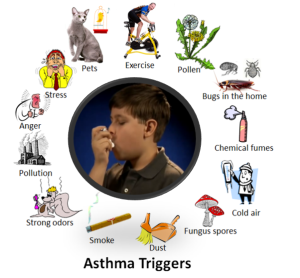

Sometimes asthma symptoms are mild and go away on their own or after minimal treatment with asthma medicine. Other times, symptoms continue to get worse. When symptoms get more intense and/or more symptoms occur, you’re having an asthma attack. Asthma attacks also are called flare-ups or exacerbations.

Figure 14.11: The different things that can trigger asthma. (Image by 7mike5000 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Image modified by adding content from a video by the CDC which is in the public domain)

Treating symptoms when you first notice them is important. This will help prevent the symptoms from worsening and causing a severe asthma attack. Severe asthma attacks may require emergency care, and they can be fatal. Asthma has no cure. Even when you feel fine, you still have the disease and it can flare up at any time.

However, with today’s knowledge and treatments, most people who have asthma are able to manage the disease. They have few, if any, symptoms. They can live normal, active lives and sleep through the night without interruption from asthma. If you have asthma, you can take an active role in managing the disease. For successful, thorough, and ongoing treatment, build strong partnerships with your doctor and other health care providers.

childhood stress

Take a moment to think about how you deal with and how stress affects you. Now think about what the impact of stress may have on a child and their development.

Of course, children experience stress and different types of stressors differently. Not all stress is bad. Normal, everyday stress can provide an opportunity for young children to build coping skills and poses little risk to development. Even more long-lasting stressful events such as changing schools or losing a loved one can be managed fairly well. But children who experience toxic stress or who live in extremely stressful situations of abuse over long periods of time can suffer long-lasting effects. The structures in the midbrain or limbic system such as the hippocampus and amygdala can be vulnerable to prolonged stress during early childhood (Middlebrooks and Audage, 2008, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). High levels of the stress hormone cortisol can reduce the size of the hippocampus and effect the child’s memory abilities. Stress hormones can also reduce immunity to disease. If the brain is exposed to long periods of severe stress it can develop a low threshold making the child hypersensitive to stress in the future. Whatever the effects of stress, it can be minimized if a child learns to deal with stressors and develop coping strategies with the support of caring adults. It’s easy to know when your child has a fever or other physical symptoms. However, a child’s mental health problems may be harder to identify.

When You Have a Concern About a CHIld. What’s in a label?

Children are continually evaluated as they enter and progress through childcare and school. If a child is showing a need, they should be assessed by a qualified professional who would make a recommendation or diagnosis of the child and give the type of instruction, resources, accommodations, and support that they should receive.

Ideally, a proper diagnosis or label is extremely beneficial for children who have education, social, emotional or developmental needs. Once their difficulty, disorder, or disability is labeled then the child will receive the help they need from parents, educators, and any other professional who will work as a team to meet the student’s individual goals and needs.

However, it’s important to consider that children that are labeled without proper support and accommodations or worse they may be misdiagnoses will have negative consequences. A label can also influence the child’s self-concept, for example, if a child is misdiagnosed as having a learning disability; the child, teachers, and family member interpret their actions through the lens of that label. Labels are powerful and can be good for the child or they can be detrimental for their development all depending on the accuracy of the label and if they are accurately applied.

A team of people who include parents, teachers, educational advocates and any other support staff will look at the child’s evaluation assessment to develop an Individual Education Plan (IEP). The team will discuss the diagnosis, recommendations, and the accommodations and/or modifications. A decision will be made regarding what is best for the child. This is the time when parents or caregivers decide if they would like to follow this plan or they can dispute any part of the process. During meetings to develop the IEP, the team is able to voice concerns and questions. Parents may feel empowered when they leave these meetings. They feel as if they are a part of the team and that they know what, when, why and how their child will be helped.

Summary

- Patterns of physical growth.

- Nutritional needs.

- Causes of obesity and the negative consequences of excessive weight gain.

- Challenges to physical health including vision, hearing, oral health, diabetes, asthma and childhood stress.

References

Asthma Canada. (n.d.). Asthma at school. Retrieved from https://asthma.ca/get-help/asthma-in-children/asthma-at-school/

Childhood Obesity Foundation. (n.d.). Is my child a healthy weight? Retrieved from https://childhoodobesityfoundation.ca/child-healthy-weight/

Children First Canada. (2020). 5 Eye-opening ways kids are affected by food insecurity. Retrieved from https://childrenfirstcanada.org/blog/5-eye-opening-ways-kids-are-affected-by-food-insecurity/

CSEP. (2021). 24 Hour movement guidelines: Children (5-11) and youth (12-18). Retrieved from https://csepguidelines.ca/guidelines/children-youth/

Dieticians of Canada. (2021). Dieticians take action on household food insecurity. Retrieved from https://www.dietitians.ca/foodinsecurity

Dieticians of Canada. (2014a). WHO growth charts for Canada: Boys. Retrieved from https://www.dietitians.ca/DietitiansOfCanada/media/Documents/WHO%20Growth%20Charts/Set-2-HFA-WFA_2-19_BOYS_SET-2_EN.pdf

Dieticians of Canada. (2014b). WHO growth charts for Canada: Girls. Retrieved from https://www.dietitians.ca/DietitiansOfCanada/media/Documents/WHO%20Growth%20Charts/Set-2-HFA-WFA_2-19_GIRLS_SET-2_EN.pdf

Findlay, S., Pinzon, J., Taddeo., D & , Katzman, D. (2010). Early onset eating disorders. Retrieved from https://cps.ca/documents/position/anorexia-nervosa-family-based-treatment

Government of Canada. (2019). Childhood obesity. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/childhood-obesity/childhood-obesity.html

Government of Canada. (2020). Canada food guide: Healthy food choices. Retrieved from https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/healthy-food-choices/

Government of Ontario. (2021). Services covered by Healthy Smiles Ontario. Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/page/services-covered-by-healthy-smiles-ontario

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). Excerpts from “Elect”. Retrieved from https://www.dufferincounty.ca/sites/default/files/rtb/Excerpts-from-Early-Learning-for-Every-Child-Today.pdf

PROOF. (2021). Household food insecurity in Canada. Retrieved from https://proof.utoronto.ca/food-insecurity/