34 6.2 The Bohr Model

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the Bohr model of the hydrogen atom

- Use the Rydberg equation to calculate energies of light emitted or absorbed by hydrogen atoms

Following the work of Ernest Rutherford and his colleagues in the early twentieth century, the picture of atoms consisting of tiny dense nuclei surrounded by lighter and even tinier electrons continually moving about the nucleus was well established. This picture was called the planetary model, since it pictured the atom as a miniature “solar system” with the electrons orbiting the nucleus like planets orbiting the sun. The simplest atom is hydrogen, consisting of a single proton as the nucleus about which a single electron moves. The electrostatic force attracting the electron to the proton depends only on the distance between the two particles. The electrostatic force has the same form as the gravitational force between two mass particles except that the electrostatic force depends on the magnitudes of the charges on the particles (+1 for the proton and −1 for the electron) instead of the magnitudes of the particle masses that govern the gravitational force. Since forces can be derived from potentials, it is convenient to work with potentials instead, since they are forms of energy. The electrostatic potential is also called the Coulomb potential. Because the electrostatic potential has the same form as the gravitational potential, according to classical mechanics, the equations of motion should be similar, with the electron moving around the nucleus in circular or elliptical orbits (hence the label “planetary” model of the atom). Potentials of the form V(r) that depend only on the radial distance r are known as central potentials. Central potentials have spherical symmetry, and so rather than specifying the position of the electron in the usual Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z), it is more convenient to use polar spherical coordinates centered at the nucleus, consisting of a linear coordinate r and two angular coordinates, usually specified by the Greek letters theta (θ) and phi (Φ). These coordinates are similar to the ones used in GPS devices and most smart phones that track positions on our (nearly) spherical earth, with the two angular coordinates specified by the latitude and longitude, and the linear coordinate specified by sea-level elevation. Because of the spherical symmetry of central potentials, the energy and angular momentum of the classical hydrogen atom are constants, and the orbits are constrained to lie in a plane like the planets orbiting the sun. This classical mechanics description of the atom is incomplete, however, since an electron moving in an elliptical orbit would be accelerating (by changing direction) and, according to classical electromagnetism, it should continuously emit electromagnetic radiation. This loss in orbital energy should result in the electron’s orbit getting continually smaller until it spirals into the nucleus, implying that atoms are inherently unstable.

In 1913, Niels Bohr attempted to resolve the atomic paradox by ignoring classical electromagnetism’s prediction that the orbiting electron in hydrogen would continuously emit light. Instead, he incorporated into the classical mechanics description of the atom Planck’s ideas of quantization and Einstein’s finding that light consists of photons whose energy is proportional to their frequency. Bohr assumed that the electron orbiting the nucleus would not normally emit any radiation (the stationary state hypothesis), but it would emit or absorb a photon if it moved to a different orbit. The energy absorbed or emitted would reflect differences in the orbital energies according to this equation:

In this equation, h is Planck’s constant and Ei and Ef are the initial and final orbital energies, respectively. The absolute value of the energy difference is used, since frequencies and wavelengths are always positive. Instead of allowing for continuous values for the angular momentum, energy, and orbit radius, Bohr assumed that only discrete values for these could occur (actually, quantizing any one of these would imply that the other two are also quantized). Bohr’s expression for the quantized energies is:

In this expression, k is a constant comprising fundamental constants such as the electron mass and charge and Planck’s constant. Inserting the expression for the orbit energies into the equation for ΔE gives

or

which is identical to the Rydberg equation for . When Bohr calculated his theoretical value for the Rydberg constant,

, and compared it with the experimentally accepted value, he got excellent agreement. Since the Rydberg constant was one of the most precisely measured constants at that time, this level of agreement was astonishing and meant that Bohr’s model was taken seriously, despite the many assumptions that Bohr needed to derive it.

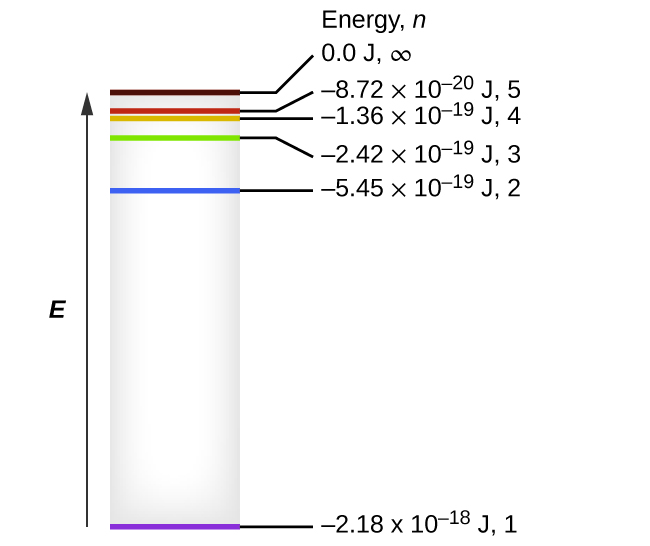

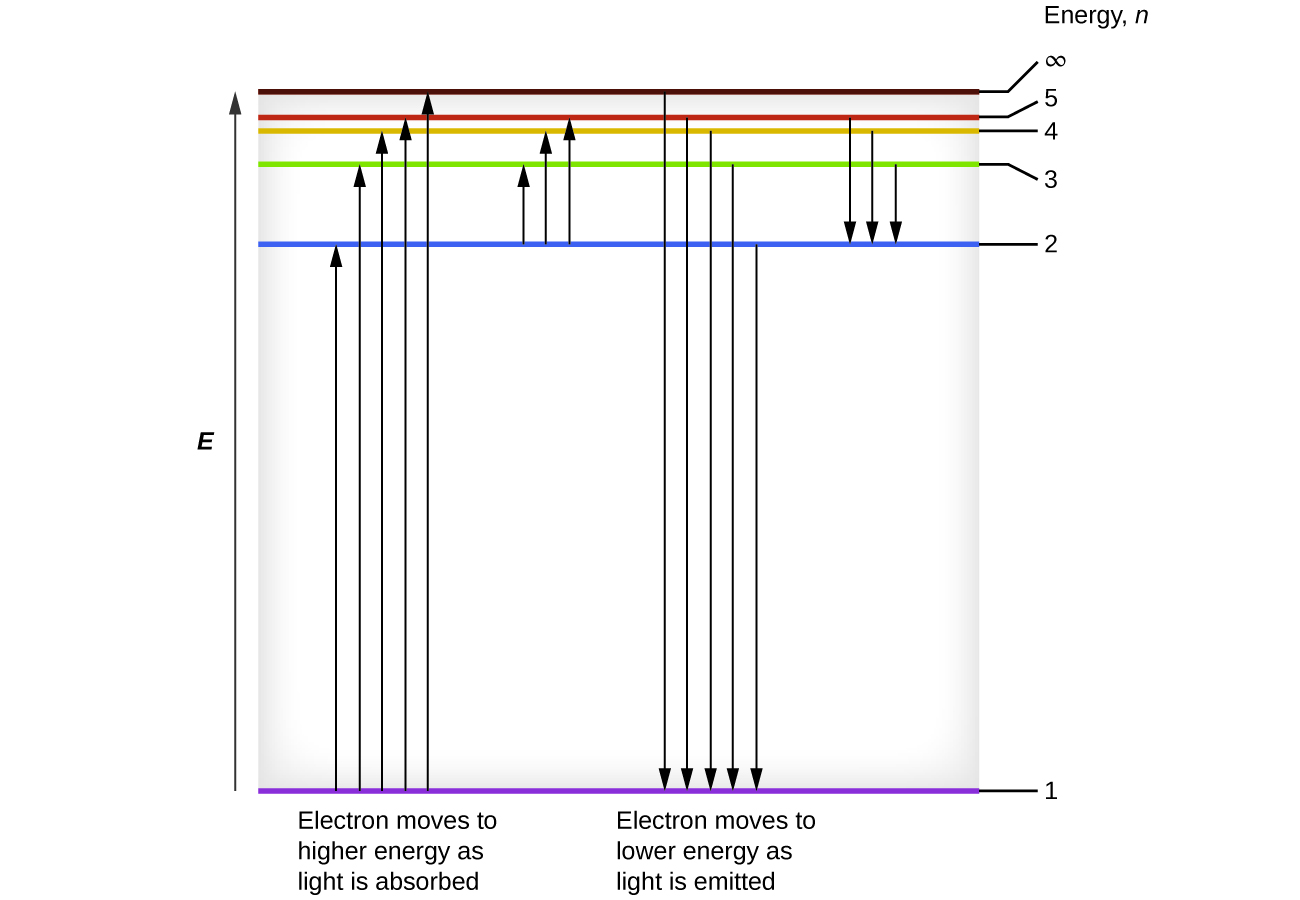

The lowest few energy levels are shown in Figure 1. One of the fundamental laws of physics is that matter is most stable with the lowest possible energy. Thus, the electron in a hydrogen atom usually moves in the n = 1 orbit, the orbit in which it has the lowest energy. When the electron is in this lowest energy orbit, the atom is said to be in its ground electronic state (or simply ground state). If the atom receives energy from an outside source, it is possible for the electron to move to an orbit with a higher n value and the atom is now in an excited electronic state (or simply an excited state) with a higher energy. When an electron transitions from an excited state (higher energy orbit) to a less excited state, or ground state, the difference in energy is emitted as a photon. Similarly, if a photon is absorbed by an atom, the energy of the photon moves an electron from a lower energy orbit up to a more excited one. We can relate the energy of electrons in atoms to what we learned previously about energy. The law of conservation of energy says that we can neither create nor destroy energy. Thus, if a certain amount of external energy is required to excite an electron from one energy level to another, that same amount of energy will be liberated when the electron returns to its initial state (Figure 2). In effect, an atom can “store” energy by using it to promote an electron to a state with a higher energy and release it when the electron returns to a lower state. The energy can be released as one quantum of energy, as the electron returns to its ground state (say, from n = 5 to n = 1), or it can be released as two or more smaller quanta as the electron falls to an intermediate state, then to the ground state (say, from n = 5 to n = 4, emitting one quantum, then to n = 1, emitting a second quantum).

Since Bohr’s model involved only a single electron, it could also be applied to the single electron ions He+, Li2+, Be3+, and so forth, which differ from hydrogen only in their nuclear charges, and so one-electron atoms and ions are collectively referred to as hydrogen-like atoms. The energy expression for hydrogen-like atoms is a generalization of the hydrogen atom energy, in which Z is the nuclear charge (+1 for hydrogen, +2 for He, +3 for Li, and so on) and k has a value of 2.179 × 10–18 J.

The sizes of the circular orbits for hydrogen-like atoms are given in terms of their radii by the following expression, in which α0α0 is a constant called the Bohr radius, with a value of 5.292 × 10−11 m:

The equation also shows us that as the electron’s energy increases (as n increases), the electron is found at greater distances from the nucleus. This is implied by the inverse dependence on r in the Coulomb potential, since, as the electron moves away from the nucleus, the electrostatic attraction between it and the nucleus decreases, and it is held less tightly in the atom. Note that as n gets larger and the orbits get larger, their energies get closer to zero, and so the limits , and

imply that E = 0 corresponds to the ionization limit where the electron is completely removed from the nucleus. Thus, for hydrogen in the ground state n = 1, the ionization energy would be:

With three extremely puzzling paradoxes now solved (blackbody radiation, the photoelectric effect, and the hydrogen atom), and all involving Planck’s constant in a fundamental manner, it became clear to most physicists at that time that the classical theories that worked so well in the macroscopic world were fundamentally flawed and could not be extended down into the microscopic domain of atoms and molecules. Unfortunately, despite Bohr’s remarkable achievement in deriving a theoretical expression for the Rydberg constant, he was unable to extend his theory to the next simplest atom, He, which only has two electrons. Bohr’s model was severely flawed, since it was still based on the classical mechanics notion of precise orbits, a concept that was later found to be untenable in the microscopic domain, when a proper model of quantum mechanics was developed to supersede classical mechanics.

Example 1

Calculating the Energy of an Electron in a Bohr Orbit

Early researchers were very excited when they were able to predict the energy of an electron at a particular distance from the nucleus in a hydrogen atom. If a spark promotes the electron in a hydrogen atom into an orbit with n = 3, what is the calculated energy, in joules, of the electron?

Solution

The energy of the electron is given by this equation:

The atomic number, Z, of hydrogen is 1; k = 2.179 × 10–18 J; and the electron is characterized by an n value of 3. Thus,

Check Your Learning

The electron in Figure 2 is promoted even further to an orbit with n = 6. What is its new energy?

Answer:

−6.053 × 10–20 J

Figure 2. The horizontal lines show the relative energy of orbits in the Bohr model of the hydrogen atom, and the vertical arrows depict the energy of photons absorbed (left) or emitted (right) as electrons move between these orbits.

Example 2

Calculating the Energy and Wavelength of Electron Transitions in a One–electron (Bohr) System

What is the energy (in joules) and the wavelength (in meters) of the line in the spectrum of hydrogen that represents the movement of an electron from Bohr orbit with n = 4 to the orbit with n = 6? In what part of the electromagnetic spectrum do we find this radiation?

Solution

In this case, the electron starts out with n = 4, so n1 = 4. It comes to rest in the n = 6 orbit, so n2 = 6. The difference in energy between the two states is given by this expression:

This energy difference is positive, indicating a photon enters the system (is absorbed) to excite the electron from the n = 4 orbit up to the n = 6 orbit. The wavelength of a photon with this energy is found by the expression . Rearrangement gives:

From Figure 2 in Chapter 6.1 Electromagnetic Energy, we can see that this wavelength is found in the infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Check Your Learning

What is the energy in joules and the wavelength in meters of the photon produced when an electron falls from the n = 5 to the n = 3 level in a He+ ion (Z = 2 for He+)?

Answer:

6.198 × 10–19 J; 3.205 × 10−7 m

Bohr’s model of the hydrogen atom provides insight into the behavior of matter at the microscopic level, but it is does not account for electron–electron interactions in atoms with more than one electron. It does introduce several important features of all models used to describe the distribution of electrons in an atom. These features include the following:

- The energies of electrons (energy levels) in an atom are quantized, described by quantum numbers: integer numbers having only specific allowed value and used to characterize the arrangement of electrons in an atom.

- An electron’s energy increases with increasing distance from the nucleus.

- The discrete energies (lines) in the spectra of the elements result from quantized electronic energies.

Of these features, the most important is the postulate of quantized energy levels for an electron in an atom. As a consequence, the model laid the foundation for the quantum mechanical model of the atom. Bohr won a Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions to our understanding of the structure of atoms and how that is related to line spectra emissions.

Key Concepts and Summary

Bohr incorporated Planck’s and Einstein’s quantization ideas into a model of the hydrogen atom that resolved the paradox of atom stability and discrete spectra. The Bohr model of the hydrogen atom explains the connection between the quantization of photons and the quantized emission from atoms. Bohr described the hydrogen atom in terms of an electron moving in a circular orbit about a nucleus. He postulated that the electron was restricted to certain orbits characterized by discrete energies. Transitions between these allowed orbits result in the absorption or emission of photons. When an electron moves from a higher-energy orbit to a more stable one, energy is emitted in the form of a photon. To move an electron from a stable orbit to a more excited one, a photon of energy must be absorbed. Using the Bohr model, we can calculate the energy of an electron and the radius of its orbit in any one-electron system.

Key Equations

Chemistry End of Chapter Exercises

- Why is the electron in a Bohr hydrogen atom bound less tightly when it has a quantum number of 3 than when it has a quantum number of 1?

- What does it mean to say that the energy of the electrons in an atom is quantized?

- Using the Bohr model, determine the energy, in joules, necessary to ionize a ground-state hydrogen atom. Show your calculations.

- The electron volt (eV) is a convenient unit of energy for expressing atomic-scale energies. It is the amount of energy that an electron gains when subjected to a potential of 1 volt; 1 eV = 1.602 × 10–19 J. Using the Bohr model, determine the energy, in electron volts, of the photon produced when an electron in a hydrogen atom moves from the orbit with n = 5 to the orbit with n = 2. Show your calculations.

- Using the Bohr model, determine the lowest possible energy, in joules, for the electron in the Li2+ ion.

- Using the Bohr model, determine the lowest possible energy for the electron in the He+ ion.

- Using the Bohr model, determine the energy of an electron with n = 6 in a hydrogen atom.

- Using the Bohr model, determine the energy of an electron with n = 8 in a hydrogen atom.

- How far from the nucleus in angstroms (1 angstrom = 1 × 10–10 m) is the electron in a hydrogen atom if it has an energy of –8.72 × 10–20 J?

- What is the radius, in angstroms, of the orbital of an electron with n = 8 in a hydrogen atom?

- Using the Bohr model, determine the energy in joules of the photon produced when an electron in a He+ ion moves from the orbit with n = 5 to the orbit with n = 2.

- Using the Bohr model, determine the energy in joules of the photon produced when an electron in a Li2+ ion moves from the orbit with n = 2 to the orbit with n = 1.

- Consider a large number of hydrogen atoms with electrons randomly distributed in the n = 1, 2, 3, and 4 orbits.

(a) How many different wavelengths of light are emitted by these atoms as the electrons fall into lower-energy orbitals?

(b) Calculate the lowest and highest energies of light produced by the transitions described in part (a).

(c) Calculate the frequencies and wavelengths of the light produced by the transitions described in part (b).

- How are the Bohr model and the Rutherford model of the atom similar? How are they different?

- The spectra of hydrogen and of calcium are shown in Figure 12 in Chapter 6.1 Electromagnetic Energy. What causes the lines in these spectra? Why are the colors of the lines different? Suggest a reason for the observation that the spectrum of calcium is more complicated than the spectrum of hydrogen.

Glossary

- Bohr’s model of the hydrogen atom

- structural model in which an electron moves around the nucleus only in circular orbits, each with a specific allowed radius; the orbiting electron does not normally emit electromagnetic radiation, but does so when changing from one orbit to another.

- excited state

- state having an energy greater than the ground-state energy

- ground state

- state in which the electrons in an atom, ion, or molecule have the lowest energy possible

- quantum number

- integer number having only specific allowed values and used to characterize the arrangement of electrons in an atom

Solutions

2. Quantized energy means that the electrons can possess only certain discrete energy values; values between those quantized values are not permitted.

4.

6. −8.716 × 10−18 J

8. −3.405 × 10−20 J

10. 33.9 Å

12. 1.471 × 10−17 J

14. Both involve a relatively heavy nucleus with electrons moving around it, although strictly speaking, the Bohr model works only for one-electron atoms or ions. According to classical mechanics, the Rutherford model predicts a miniature “solar system” with electrons moving about the nucleus in circular or elliptical orbits that are confined to planes. If the requirements of classical electromagnetic theory that electrons in such orbits would emit electromagnetic radiation are ignored, such atoms would be stable, having constant energy and angular momentum, but would not emit any visible light (contrary to observation). If classical electromagnetic theory is applied, then the Rutherford atom would emit electromagnetic radiation of continually increasing frequency (contrary to the observed discrete spectra), thereby losing energy until the atom collapsed in an absurdly short time (contrary to the observed long-term stability of atoms). The Bohr model retains the classical mechanics view of circular orbits confined to planes having constant energy and angular momentum, but restricts these to quantized values dependent on a single quantum number, n. The orbiting electron in Bohr’s model is assumed not to emit any electromagnetic radiation while moving about the nucleus in its stationary orbits, but the atom can emit or absorb electromagnetic radiation when the electron changes from one orbit to another. Because of the quantized orbits, such “quantum jumps” will produce discrete spectra, in agreement with observations.