4.7 Understanding Decolonization, Indigenization, and Reconciliation

Reconciliation requires constructive action on addressing the ongoing legacies of colonialism that have had destructive impacts on Aboriginal peoples’ education, cultures and languages, health, child welfare, the administration of justice, and economic opportunities and prosperity. (2015, p. 3)

We all have a role to play. As noted by Universities Canada, “[h]igher education offers great potential for reconciliation and a renewed relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada.” (2015) Similarly, Colleges and Institutions Canada notes that “Indigenous education will strengthen colleges’ and institutes’ contribution to improving the lives of learners and communities.” (2015) These guides provide a way for all faculty and staff to Indigenize their practice in post-secondary education.

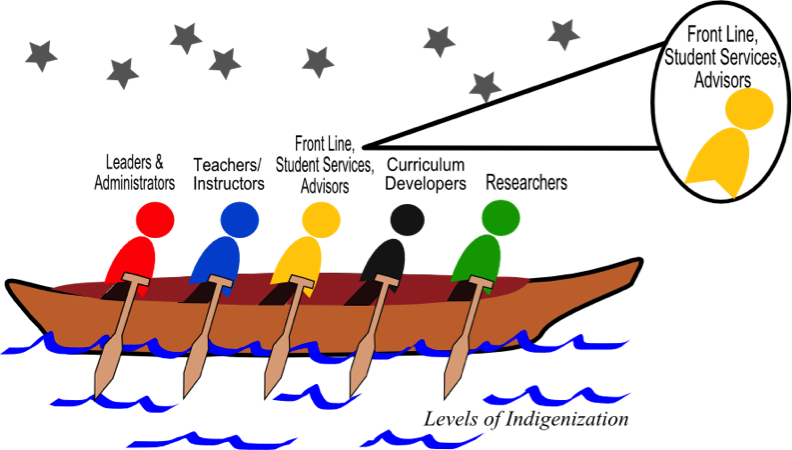

The Indigenization Project can be described as an evolving story of how diverse people can journey forward in a canoe (Fig 0.1). In Indigenous methodology, stories emphasize our relationships with our environment, our communities, and with each other. To stay on course, we are guided by the stars in the sky, with each star a project principle: deliver holistically, learn from one another, work together, share strengths, value collaboration, deepen the learning, engage respectfully, and learn to work in discomfort. As we look ahead, we do not forget our past.

The canoe holds Indigenous Peoples and the key people in post-secondary education whose roles support, lead, and build Indigenization. Our combined strengths give us balance and the ability to steer and paddle in unison as we sit side by side. The paddles are the open resources. As we learn to pull together, we understand that our shared knowledge makes us stronger and makes us one.

The perpetual motion and depth of water reflects the evolving process of Indigenization. Indigenization is relational and collaborative and involves various levels of transformation, from inclusion and integration to infusion of Indigenous perspectives and approaches in education. As we learn together, we ask new questions, so we continue our journey with curiosity and optimism, always looking for new stories to share.

We hope these guides support you in your learning journey. As open education resources they can be adapted to fit local context, in collaboration with Indigenous Peoples who connect with and advise your institution. We expect that as more educators use and revise these guides, they will evolve over time.

How to use and adapt this information

We explore relationships between the institution, students, and Indigenous communities. These relationships are interconnected and are guided by shared values of Indigenization to both improve the educational and employment experiences of all students, faculty, and staff across the institutions. It also explores how Elders, Indigenous community members, and community education partners are heard and included in the educational experience. This guide reflects a holistic way to serve Indigenous students.

Media Attributions

- Fig 1.0 First Peoples House University of Victoria © US Embassy Canada is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

Introduction to Working with Indigenous

As a staff member working in the front lines of a public post-secondary institution, you spend key moments with Indigenous students as they prepare to enroll, look for assistance and services during their time in programs, and seek information for transition between programs and institutions. While service to students is paramount, there are critical times when you also:

- Help Indigenous students feel a sense of welcoming and belonging

- Share information to best inform their choices

- Support their capacity to navigate the necessary systems

- Refer them to supports that are culturally and situation specific

- Help them move to the next stages of learning to meet their vision of success

- Show compassion and actively listen during interactions

- Support students so they feel confident to move onward

Since the release of the 1990 Green Report,[1] public post-secondary institutions across the province have sought to transform systems and processes to be inclusive and respect the diverse needs of Indigenous students and community educational partners. This strategy has also spread across the country; Colleges and Institutes Canada initiated the Indigenous Education Protocol[2] in 2014 and in 2015, Universities Canada released Principles on Indigenous Education[3] to support institutional structures and approaches to support Indigenous self-determination and strengthen relationships.

Many Indigenous students are first-generation learners at post-secondary institutions, and their interactions with front-line staff and service providers inform how they share their experience with their family and community. One negative experience can cause harm and mistrust. Positive experiences help Indigenous students feel respected and help to build their trust with staff and faculty. This can lead to future generations wanting to further their post-secondary education. This guide is an opportunity for you to better understand Indigenous students and to figure out ways both you and your area or department can work to ensure supportive student experiences. By pulling together we can facilitate student success and contribute to long-term improvements for all Indigenous students and communities.

- The “Green Report” is the Report of the Provincial Advisory Committee on Post-Secondary Education for Native Learners. It provided a comprehensive look at Indigenous training needs in post-secondary education and its 21 recommendations ranged from developing Indigenous advisory boards to providing culturally relevant student services for Indigenous students. ↵

- Indigenous Education Protocol: https://www.collegesinstitutes.ca/policyfocus/indigenous-learners/protocol/ ↵

- Principles on Indigenous Education: https://www.univcan.ca/media-room/media-releases/universities-canada-principles-on-indigenous-education/ ↵

Culture is based on beliefs, values, economic status, perceptions, and actions and is influenced from what you learned from your family, your community, and society. Intercultural learning is a way to hold more than one view in an equitable way. How you perceive other cultures and the ability to view from a different culture takes personal reflection, education, and conscious effort. While there is no way you can totally understand another’s culture, you can be aware of your own culture and your position in a growing relationship.

As you work through this section, take a moment to reflect on the following questions:

- What do you hold as important when you work with students?

- Do you sometimes not understand why an interaction with a student goes the way it does? Is it because of miscommunication or a cultural misconnection?

- Do you take the time to try to see a situation from another viewpoint?

Purpose of this section

This section is intended to help you develop an understanding of the meaning and importance of Indigenization, decolonization, and reconciliation, and how you can participate in Indigenization at your institution. We explore the following topics:

- Decolonizing and Indigenizing as an unlearning and relearning process

- Pathways toward reconciliation

- Becoming an ally

This section can take up to two hours to complete.

Note: The sections “Decolonization and Indigenization,” “Pathways Toward Reconciliation,” and “Becoming an Ally” include information that was originally used in the Curriculum Developers Guide.

Decolonization and Indigenization

If we want to contribute to systemic change, we need to understand the concepts of decolonization, Indigenization, and reconciliation.

Decolonization

Decolonization is the process of deconstructing colonial ideologies of the superiority and privilege of Western thought and approaches. On the one hand, decolonization involves dismantling structures that perpetuate the status quo and addressing unbalanced power dynamics. On the other hand, decolonization involves valuing and revitalizing Indigenous knowledge and approaches and weeding out settler biases or assumptions that have impacted Indigenous ways of being. For non-Indigenous people, decolonization is the process of examining your beliefs about Indigenous Peoples and culture by learning about yourself in relationship to the communities where you live and the people with whom you interact.

We work in systems that perpetuate colonial ideals and privilege Western ways of doing. For example, many student services use forms and procedures instead of first initiating relationships with students. This is a colonial process that excludes rather than includes. Also, how libraries catalogue knowledge is Western and colonial.

Decolonization is an ongoing process that requires all of us to be collectively involved and responsible. Decolonizing our institutions means we create spaces that are inclusive, respectful, and honour Indigenous Peoples.

The call for decolonizing education and including Indigenous ways of knowing and being in education was first articulated in 1972 in “Indian control of Indian education” [PDF][1] by the National Indian Brotherhood (now the Assembly of First Nations).

“We want education to give our children the knowledge to understand and be proud of themselves and the knowledge to understand the world around them.” (p. 1)

Indigenization

Indigenization is a collaborative process of naturalizing Indigenous intent, interactions, and processes and making them evident to transform spaces, places, and hearts. In the context of post-secondary education, this involves including Indigenous perspectives and approaches. Indigenization benefits not only Indigenous students but all students, teachers, staff members, and community members involved or impacted by Indigenization.

Indigenization seeks not only relevant programs and support services but also a fundamental shift in the ways that institutions:

- Include Indigenous perspectives, values, and cultural understandings in policies and daily practices.

- Position Indigenous ways of knowing at the heart of the institution, which then informs all the work that we do.

- Include cultural protocols and practices in the operations of our institutions.

Indigenization values sustainable and respectful relationships with First Nation, Métis, and Inuit communities, Elders, and organizations. When Indigenization is practiced at an institution, Indigenous people see themselves represented, respected, and valued and all students benefit. Indigenization, like decolonization, is an ongoing process, one that will shape and evolve over time.

Indigenization is not an “Indigenous issue,” and it is not undertaken solely to benefit Indigenous students. Indigenization benefits everyone; we all gain a richer understanding of the world and of our specific location in the world through awareness of Indigenous knowledge and perspectives. Indigenization also contributes to a more just world, creating a shared understanding that opens the way toward reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. It also counters the impacts of colonization by upending a system of thinking that has typically discounted Indigenous knowledge and history.

- Indian control of Indian education: http://www.oneca.com/IndianControlofIndianEducation.pdf ↵

Decolonizing and Indigenizing as an Unlearning and Relearning Process

Recognizing the historical and contemporary colonial systems and practices within our educational institutions and broader society requires all of us to self-reflect and think about the impact of colonization. It also requires us to help influence change in the broader systems and societies within which we operate. “[I]nstitutional reform must be undertaken on multiple levels, by all peoples in the academic community, and result in a dramatically different structure, relationships, goals, and outcomes” (Pete, 2016, p. 81). We must go beyond having “decolonization as a metaphor” (Tuck & Yang, 2012) but as conscious, living part of our lives.

Working together encourages us to think of decolonization as a reciprocal partnership required for Indigenous people to participate meaningfully in the opportunities offered by our institutions. This means examining how students come in to institutions, how they move throughout the supports, and how to support positive transformation and self-determination.

Pathways Toward Reconciliation

Reconciliation is not an Aboriginal problem – it involves all of us.

– Chief Justice Murray Sinclair (CBC, 2015)

Reconciliation

Reconciliation is about addressing past wrongs done to Indigenous Peoples, making amends, and improving relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to create a better future for all.

The work of Indigenization is a growing focus in this era of reconciliation, which has been driven forward by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), a multi-year investigation of the residential school system. The TRC gathered information in a variety of ways about the historical and contemporary injustices toward Indigenous Peoples from across the nation. The release of the Honouring the Truth, Reconciling the Future: Summary of Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in June of 2015 marked an important moment in the history of Canada. In the context of reconciliation, Indigenization is one way in which we can contribute to working toward a stronger shared future as Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

The report, with its 94 Calls to Action, emphasizes the need for education to play a key role in service of justice and resurgence of Indigenous Peoples, and Indigenous communities are looking at post-secondary institutions to be leaders in responding to the TRC Calls to Action and in working to support Indigenous education in meaningful, concrete, and sustainable ways. Essential to this work is placing Indigenous perspectives at the centre of the work being done, or, as Marie Battiste has said, “Nothing about us without us” (quoted in Cote-Meek, 2017). It means we are moving towards processes of truth and reconciliation and transforming the educational system into spaces that are inclusive, respectful, and honour Indigenous people.

Given the colonial context of Canadian education, there is work to be done to decolonize our policies and practices to de-centre Western approaches and being to re-centre Indigenous ways of knowing, being, learning, and teaching. Mindful of the need for truth and reconciliation, this work is guided by a relatively straightforward question:

Are we making the institution a better place for those who come after us?

While the recent context of reconciliation has brought new levels of attention to this work, we acknowledge the long history of Indigenous faculty and staff and allies in supporting Indigenous students and advocating for change within institutions, and respectfully working to empower Indigenous communities.

Moving Forward, Reconciling Intent, Purpose, and Practice

Moving forward means ongoing self-reflection and assessment of one’s own individual roles and responsibilities to supporting Indigenous students, and the following sections will guide you through this process. Moving forward also must come with clear financial and human resources support to provide ongoing professional development opportunities and targeted hiring practices.

When surveyed, BC Aboriginal post-secondary coordinators indicated that hiring Indigenous people in student services and other front-line services as the most supportive way to help with Indigenization in an institution.

Front-line services also require a way to transform institutional culture so the values of Indigenization continue. Too often, champions who initiate Indigenized practices and relationships are recognized as innovators to the department and institution; very rarely do these practices and relationships become common procedure or guiding policy. When the champion retires or changes jobs, the practice and relationship ceases. Staff engaging in this decolonizing, Indigenizing, and reconciliation practice need to be supported in their intentions, and they need to have space and time to discuss the challenges and celebrate areas of growth and success.

Becoming an ally

Acknowledging the overt and systemic forms of racism and discrimination within public post-secondary institutions is a core part of decolonization. It’s also important to understand that by shifting individual mindsets and practices, we can make structural changes in institutional cultures, policies, and programs, thus Indigenizing the institution and ourselves. Becoming an ally is an important practice that addresses how to do this.

An ally is someone from a privileged group who is aware of how oppression works and struggles alongside members of an oppressed group to take action to end oppression. Anne Bishop explains:

Allies are people who recognize the unearned privilege they receive from society’s patterns of injustice and take responsibility for changing these patterns. Allies include men who work to end sexism, white people who work to end racism, heterosexual people who work to end heterosexism, able-bodied people who work to end ableism, and so on. Part of becoming an ally is also recognizing one’s own experience of oppression. For example, a white woman can learn from her experience of sexism and apply it in becoming an ally to people of colour, or a person who grew up in poverty can learn from that experience how to respect others’ feelings of helplessness because of a disability.

If you are a non-Indigenous person engaged in the work of Indigenization, you can better understand your role in this movement as being an ally to Indigenous people. An ally:

- does not put their own needs, interests, and goals ahead of the Indigenous people they are working with.

- has self-awareness of their own identity, privilege, and role in challenging oppression.

- is engaged in continual learning and reflection about Indigenous cultures and history.

Summary

Positioning yourself to support the transformation of services and supports for to Indigenous students and Indigenous communities is guided by national processes, provincial priorities, and relationships in your region. Together we can look at how to create an opportunity for privileging Indigenous ways of doing and being to better serve and support Indigenous students and communities at our institutions.

Activities

Activity 1: Locate yourself

Type: Individual

Time: 30 minutes

After reading this section, consider the following questions:

- How does your personal background and identity impact your knowledge and experience of Indigenous Peoples?

- What is your current relationship to Indigenous Peoples?

- What changes do you want to make in my relationship to Indigenous Peoples?

- How do you view your role in Indigenization at your institution?

Activity 2: Journey towards decolonization

Type: Individual

Time: 30 minutes

Watch this five-minute video entitled Keep Calm and Decolonize. Walking is Medicine.[1] Legendary filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin shares a story of decolonization from the Nishiyuu walkers.

- Why is it important to have decolonization as part of our work in responding to the TRC’s Calls to Action?

- What work can you undertake to decolonize your practice and views?

Activity 3: Building allyship

Type: Individual

Time: 1 hour

Read the following three blog entries:

Overcoming the Fear of Being Called a Racist: White Student Affairs Professionals Working for Racial Liberation[3]

White People Owning our Whiteness & Resistance[4]

- What are three intentional practices you could engage in to build/enrich ally relationships with Indigenous colleagues, faculty, Elders, students, and community members?

- What is the current representation of Indigenous educational leadership and staff at your institution? In your department?

Attribution:

“Pulling Together: A Guide for Front-Line Staff, Student Services, and Advisors “ by Ian Cull; Robert L. A. Hancock; Stephanie McKeown; Michelle Pidgeon and Adrienne Vedan is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Reference:

- Keep Calm and Decolonize. Walking is Medicine video: https://youtu.be/qxDFtIDliAg

- Becoming an Ally: https://web.archive.org/web/20180129135300/http://becominganally.ca/Becoming_an_Ally/Home.html

- Overcoming the Fear of Being Called a Racist: https://web.archive.org/web/20200106060858/http://convention.myacpa.org/houston2018/overcoming-fear/

- White People Owning our Whiteness & Resistance: https://web.archive.org/web/20201127112311/http://convention.myacpa.org/houston2018/white-people-owning-whiteness-resistance/