1.5 Gender, Stigma and Substance Use

When I first started in the divorce, um, when we first separated, I was straight. I was tryin’ to do right. I had the kids in church. And it got so hard, and somebody was always goin’ “well if you did this if you did that,” and I started feelin’ beneath. Uh, when I had the car wreck, I knew one way I could support my kids—I started sellin’ drugs.(1)

Gender, as we discussed is one of the social determinants of health. Have you thought about how gender plays a role in substance use disorders? Researchers suggest there are “environmental, sociocultural and developmental influences” (2) when it comes to sex, gender and substance use. This means how a person is born regarding their biological sex (male or female), as well as how they identify (gender), plays a role in their substance use and in their development of substance use disorders.

Please watch the following video to explore sex, gender and substance use(3).

Sex, Gender and Addiction, by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA/NIH). NIDA grantee Rajita Sinha discusses the importance of considering sex and gender differences while studying the causes and treatment of substance use disorders, including the differences between sex and gender; how stress affects men and women differently, and how various drugs can affect the sexes. Dr. Sinha is a Professor of Neurobiology and Child Study in the Department of Psychiatry at Yale University.

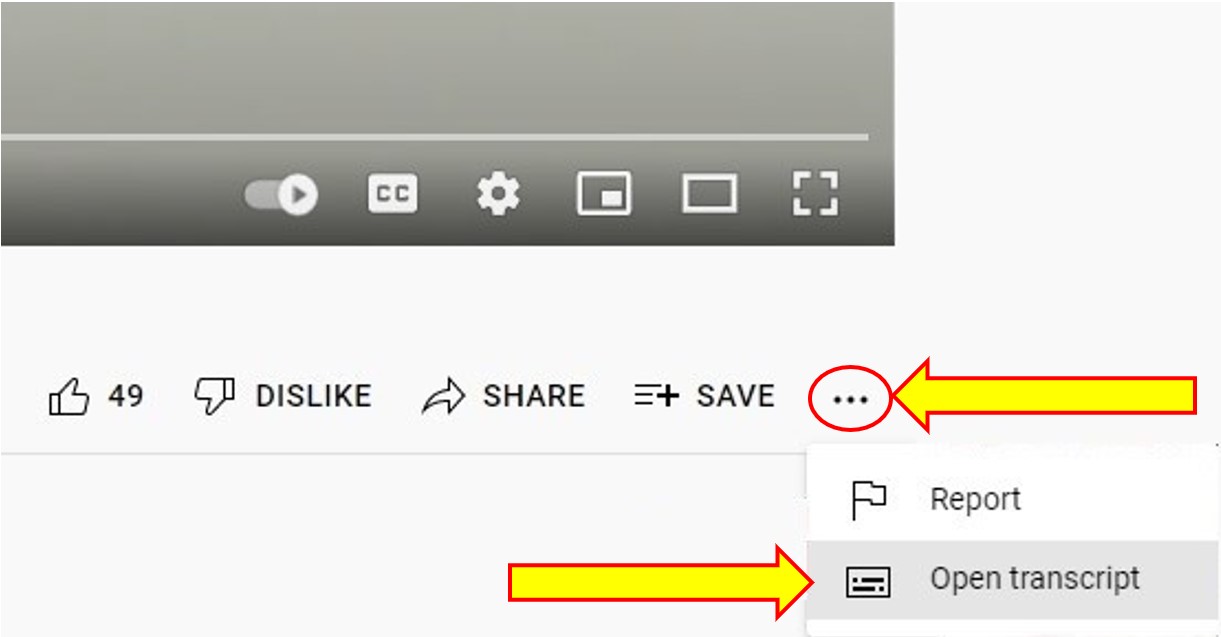

Transcript

Race and gender, as intersections of identity, also play a role in substance use and the development of a substance use disorder. Research suggests substance use disorders do differ by both biological sex and by gender(4). Subsequently, there has been an increase in woman-focused research, as the majority of current treatment supports and services are still misinformed by research with a “male-as-norm” bias. (5)

Review the Table on Sex Differences in Substance Use. This is important to be aware of, as we are exploring the social determinants of health and beginning to tackle racism, sexism, and the stigma associated with substance use.

Food For Thought

- Why do you think we should be aware of sex and gender when discussing substance use?

- What do you think are some issues specific to sex and gender for those who use substances?

Women as a gendered group face greater stigmatization than men for using drugs since they go against the character traits of perceived female identity. The stigma of drug use is also greater for mothers since they are expected to be the caregivers, raise children, and be more family oriented than fathers (6)

What this suggests is society that societal expectations of women result in moral judgments and women are judged for using substances. As Social workers, it is important to be aware of these stigmas and judgments. When we think about women who use substances and those who have a substance use disorder, we must examine our assumptions. We reflect so we can provide non-judgmental services and ensure the research we are using addresses “unexamined assumptions about how women “should” behave” and how these “have influenced research agendas”(7). These assumptions consequently impact availability of evidence-based services and programs for treatment and prevention. How can we We also must be aware that in general, “women report more problems related to health and mental health, as well as more past trauma and abuse (physical and sexual), and experience more sexual problems. Women are more likely to begin using drugs after a specific traumatic event, and to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder”.(8) How can we ensure that a program for women who live with a substance use disorder is the best it can be?

Several years ago, the United Nations developed a list of the issues that are specific to women who have substance use disorders. Of note is the association between substance use disorders and all forms of interpersonal violence (physical, sexual, and emotional) in women’s lives (9). To engage with people who identify as women, Social Service workers must be aware of the following issues:

- Shame and stigma

- Physical and sexual abuse

- Relationship issues

- Fear of losing children

- Fear of losing a partner

- Needing a partner’s permission to obtain treatment

These issues are not solely issues for a Canadian audience, they are worldwide. Based on these issues, the United Nations developed a list of concerns practitioners should address when supporting women with substance use disorders. These include:

- Lack of sex and gender-specific services for women

- Not understanding women’s issues

- Long waiting lists

- Lack of childcare services

- Lack of financial resources

- Lack of clean/sober housing

- Poorly coordinated services (10).

Activities

- Review the UN lists above.

- Brainstorm any missing concerns you think would be important to include.

- Imagine you are providing a program for women with substance use disorders. What would you need to do to ensure your program meets UNODC recommendations?

To support women’s health, Social workers must also address the stigma of women using substances. Rather than provide supportive and well-rounded (“wrap-around”) services, some services may come from a place of moral judgment, which puts women who use substances in a greater position for marginalization and reduced health outcomes. “Women living with a history of substance use and addiction encounter many barriers when trying to access forums that are directly related to their life issues” (11). Women have reported “feeling unsupported and judged” (12) which negatively impacts their mental health and may prevent them from further accessing health care. Being aware of the societal issues related to women and substance use is one area Social workers can make a real difference, through providing not only a judgment-free service, but a service that provides supportive services based on the UNODC recommendations. Gender based services that also support a harm reduction approach and address women’s needs are an important part of a social service workers toolbox.

Activities

- Research harm reduction.

- Why is harm reduction important in providing services to women?

Harm reduction is simply that, reducing the harms that are associated with substance use. Harm reduction in women’s programming should be comprehensive, addressing the issues identified above. For example, when working with women who are pregnant and using substances, some people may want to judge. Please watch the following clip and then answer the questions in the activity below.

Activities

- Research harm reduction.

- Why is harm reduction important in providing services to women?

Harm reduction is simply that, reducing the harms that are associated with substance use. Harm reduction in women’s programming should be comprehensive, addressing the issues identified above. For example, when working with women who are pregnant and using substances, some people may want to judge.

WATCH

Reflections on Practice: Pregnant Users NFB Video – Nettie Wild – 2007 | 1 min NFB Video: Bevel Up-Becky and Liz

Street nurse Caroline Brunt reflects on the challenges she faces when working with pregnant women who use drugs, and the importance of not judging the mother.

Activities

- Brainstorm a list of society’s attitudes towards pregnant women using substances.

- How do you think moms who use substances might be judged by a healthcare provider?

- How do you think moms who use substances might be judged by a workplace or by community services?

- What risks can this lead to?

- How can you support a mom who is using substances or has a substance use disorder?

Women are becoming increasingly at risk for substance use disorders; for example, the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse has suggested women’s use of alcohol has been on the rise since 2004(13). In 2020, “30.5% of women of reproductive age reported consuming alcohol weekly in the past year and 18.3% reported engaging in heavy alcohol consumption” (14).

Food For Thought

- Why do you think women are increasing their substance use?

- Why do we need to know about women’s drinking habits?

- Why do you think women are increasingly at risk of substance use disorders?

There are many issues to be aware of when it comes to gender and substance use. Whether providing support for women who have a substance use disorder or treatment for women’s substance use disorders, Social Service workers must acknowledge the realities of women’s lives, the stigma they face: “women with histories of addiction and incarceration face stigma regarding their roles in society, particularly with regard to their roles as mothers and women” (15) and the high prevalence of violence and other types of abuse (16). Services must be comprehensive, from prevention through to treatment and recovery for women and girls, and should be based on a holistic and woman-centered approach that acknowledges their psychosocial needs(17).

Attribution:

Exploring Substance Use in Canada by Julie Crouse is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, with minor revisions for clarity and ease of use.

References

- Lee, N., & Boeri, M. (2017). Managing stigma: Women drug users and recovery services. Fusio: the Bentley Undergraduate Research Journal, 1(2), 65–94. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6103317/

- Becker, J. B., McClellan, M. L., & Reed, B. G. (2017). Sex differences, gender, and addiction. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 95(1-2), 136–147. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.23963

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2019). Sex, gender and addiction. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nP–FR198Cc

- Becker, J. B., McClellan, M. L., & Reed, B. G. (2016). Sociocultural context for sex differences in addiction. Addiction Biology, 21(5), 1052-1059. https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12383

- Kruk, E., & Sandberg, K. (2013). A home for body and soul: substance using women in recovery. Harm reduction journal, 10, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-10-39

- Lee, N., & Boeri, M. (2017). Managing stigma: Women drug users and recovery services. Fusio: the Bentley Undergraduate Research Journal, 1(2), 65–94. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6103317/

- Becker, J. B., McClellan, M. L., & Reed, B. G. (2017). Sex differences, gender, and addiction. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 95(1-2), 136–147. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.23963

- Kruk, E., & Sandberg, K. (2013). A home for body and soul: substance using women in recovery. Harm reduction journal, 10, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-10-39

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2018). Women and drugs; drug use, drug supply and their consequences. https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018/prelaunch/WDR18_Booklet_5_WOMEN.pdf

- Ibid.

- Paivinen, H., & Bade, S. (2008). Voice: Challenging the stigma of addiction -a nursing perspective. International Journal of Drug Policy, 19(3), 214-219 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.02.011

- Eggertson, L. (2013). Stigma, a major barrier to treatment for pregnant women with addictions: Canadian Medical Association Journal, 185(18), 1562. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-4653

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. (2004). Girls, women and substance use. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-05/ccsa-011142-2005.pdf

- Varin, M., Palladino, E., Hill MacEachern, K., Belzak, L. & Baker, M. M. (2021). At a glance: Prevalance of alcohol use among women of reproductive age in Canada. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada Journal, 41(9), 267-272. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.41.9.04

- Gunn, A. J., & Canada, K. E. (2015). Intra-group stigma: Examining peer relationships among women in recovery for addictions. Drugs, 22(3), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2015.1021241

- Covington, S. (2008). Women and addiction: A trauma-informed approach. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 40(Sup5), 377-385. https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12383

- Covington, S. (2008). Women and addiction: A trauma-informed approach. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 40(Sup5), 377-385. https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12383