4.8 Who are Indigenous Students

Media Attributions

- Fig 2.1: ACS_6712 (Large) © artic_council is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

Introduction

Students enter our space and are free to be who they are – without teaching, answering, debating, dialoguing 500 years of colonization. More physical (and mental) spaces need to be like this.”

– Vanessa McCourt (2018, p. 14)

Identity grounds us, it guides us, and it gives us a foundation of who we are and what we can do. Every day, Indigenous students interact with staff in student services, academic advising, libraries, bookstores, and counselling services. This section considers ways we can ensure that we respect Indigenous identities and provide an environment that is accessible, inclusive, and safe for all students. We look at the diversity of Indigenous students and how their identity is often threatened by stereotypes and myths. We also explore Indigenous ways of knowing and being. To be an ally, it is helpful to understand how Indigenous students’ needs and worldviews differ from other student populations.

Purpose of this section

In this section, we look at how diverse Indigenous post-secondary students are. We also look at how education and experiences can form long-lasting relationships and positive experiences in post-secondary education. Topics include:

- Indigenous student diversity

- Myths that impact Indigenous student experience

- Indigenous ways of knowing and being

This section will take two to four hours for group activities and individual exploration.

Indigenous Student Diversity

Indigenous students attending BC post-secondary institutions represent over 600 distinct First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities from across Canada. Many institutions also recognize Native Americans as Indigenous students. Indigenous student enrolment is increasing, and these students approach post-secondary through two streams:

- High school graduates (in 2015/16 the Ministry of Education reported [PDF][1] 64 percent of Indigenous students completed high school, an increase of 7 percent in the past six years)

- Non-traditional students (mature students without Grade 12 credentials who are upgrading their high school marks)

Indigenous students are also parents and community leaders with a great breadth and depth of life experience. Some students will come to post-secondary institutions confident in who they are as Indigenous people; they have grown up within their culture, understand their language, and are strongly affirmed in their identities. Others, due to systemic impacts of colonization, such as residential schools, the 60s scoop, intergenerational trauma, and lost family histories, will come to post-secondary education in search (or even in denial) of their Indigenous identities. Indigenous identities are further complicated by where students grew up. Whether a student grew up in an urban centre or rural community or off-reserve or on-reserve will have an impact on their Indigenous identity.

Support services within post-secondary institutions

Keeping this diversity in mind, providing culturally relevant support services is critical to Indigenous student success. Many of the post-secondary institutions have either departments or Indigenous academic coordinators or advisors[2] for students to connect and interact throughout their enrolment and completion of programs.

The role of the an Indigenous academic coordinator has not always been easy to define as Janice Simcoe from Camosun College noted in 2002:

From the first days, we realized that the position of First Nations coordinator is a challenging one. It is one thing to say that these positions were supposed to support student success. It was quite another to define what that meant and develop ways to do it. We needed to examine the academic, financial, social, and cultural needs of the students we had been hired to support, and establish or learn ways to help them meet these needs. That was, and continues to be, an extraordinary challenge … Over the years we have evolved. There were only about nine of us at that first gathering. Now there are at least 52 people in the system who have official responsibility to promote First Nations student success. (Ministry of Advanced Education, p. 1-2)

Today Indigenous academic coordinators or advisors support Indigenous student diversity by meeting them where they are at in their cultural and community identity. Students will seek out different things; for instance:

- Students learning more about who they are as an Indigenous person will often seek cultural supports for their personal journey to make a deeper connection to their culture or understand what it means to be Indigenous.

- Students secure in their cultural identity will seek a feeling of community, and make the Indigenous student services department their culturally safe home away from home.

If your campus has an Indigenous student services department, the advisors or coordinators in this department can be a great support for Indigenous students and for anyone wanting advice about Indigenous issues. It’s important to keep in mind that people working in Indigenous student services are often very busy as the holistic services they provide also includes connecting with Indigenous communities; depending upon how many Indigenous advisors and coordinators are in your institution, you may or may not have a delayed response to your requests.

- Ministry of Education Report: http://www.bced.gov.bc.ca/reports/pdfs/ab_hawd/Public.pdf ↵

- The BC Aboriginal Post-Secondary Advisory (BCAPSA) is a network of advisors and coordinators from across the province who provide services and supports to Indigenous students and work with Indigenous communities. ↵

Myths that Impact Indigenous Student Experience

Indigenous students are not always in culturally safe spaces on campus. The concept of cultural safety recognizes that we need to be aware of and challenge unequal power relations at all levels: individual, family, community, and society. The reality is that many Indigenous students experience racial microaggressions daily and this ongoing harm creates feelings of isolation and unwelcomeness. A racial microaggression is a “subtle behaviour that [conveys] hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to persons of marginalized groups” (Shotton, 2017, p. 33). Negative messages are based on myths and stereotypes. Below are a few common misconceptions to dispel as you work with Indigenous students and build your allyship.

Indigenous students get 100 percent free education

Not all Indigenous students receive funding. There is a federal funding program called the Post-Secondary Student Support program,[1] but only status First Nations and Inuit post-secondary students are eligible for funding under this program. This program is underfunded, with little budgetary increase since the mid-1990s. This causes First Nations and Inuit-designated organizations, who administer the annual allotted funds to their membership, to ration who, how, and what is funded. For example, some eligible students will have just their books and supplies paid for while others will get their tuition if they enrol full-time. Some programs may not be eligible for funding, including any continuing education programs and some online programs. For those students who must relocate to attend college or university, costs such as housing, day care, and transportation, are often not covered. Métis and non-status First Nations students are not eligible for Post-Secondary Student Support funding, so they must seek student aid, scholarships, and bursaries. Métis students can also apply to Métis Nation BC for post-secondary funding through its Indigenous Skills and Employment Training Program,[2] which is funded by Employment and Social Development Canada. Moreover, BC First Nations who have signed modern treaty agreements (for example, Nisga’a First Nation, Maa-nulth First Nations, Tsawwassen First Nation, Tla’min First Nation) no longer have access to the Post-Secondary Support Program and may or may not be able to provide post-secondary funding to their members. For more information about funding programs for Indigenous students, please see Appendix B.

Indigenous students are “underprepared”

Not Quite. Many Indigenous students are the first generation of learners to attend a post-secondary institution, so they may not know the processes involved in enrolment, transition, and graduation. Some students may need academic support to transition to the post-secondary classroom (for example, they may require tutors or academic support for numeracy, literacy, and technology); however, many will come fully prepared academically.

Students of mixed ancestry are Métis

Not all “mixed blood” people are Métis. The Métis are members of an Indigenous nation with roots in the North American fur trade. While some of their ancestors are European, the salient characteristic of Métis identity is based on shared histories, cultural practices, and community life. A person is Métis because they are descended from Métis ancestors and recognized by Métis relatives and communities, not because they are of mixed ancestry (Hancock, 2017). For further information, please see the Métis Bibliography [PDF],[3] a supplement developed for the Indigenization Project.

If you’ve met one Indigenous student, you’ve met them all

Not true. Indigenous Peoples’ experiences cannot be homogenized; therefore, each student must be understood in relationship to their cultural identity, diverse spiritual practices, and experiences. For example, not all Indigenous people come from poverty, suffer from violence, or have lived on reserve. Understanding students’ socio-political circumstances is helpful in your role as an ally and service provider as is understanding the effects of colonization, residential schools, and other complex systemic issues facing Indigenous Peoples. However, we should not assume all students come from the same circumstance and that Indigenous people are all harmed.

Indigenous students are “spiritual”

Indigenous students are culturally diverse. Not all Indigenous people have the same spiritual practices. For example, not all Indigenous Peoples take part in smudging ceremonies or pow wows (these are primarily practiced on the prairies), and not all Indigenous people participate in feasts and potlatches (these traditions are practiced by Indigenous Peoples on the Northwest Coast). Spiritual practices are influenced by worldviews, language, and practices. Also, the effects of colonization, such as residential schools, mean some Indigenous students also practice faith-based religions either alongside or separate from their traditional cultural practices. Spirituality must be thought of as diverse as Indigenous Peoples themselves and we can’t make assumptions about what role spirituality plays in an Indigenous person’s life without knowing the individual.

- Post-Secondary Student Support program: https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100033682/1100100033683 ↵

- Indigenous Skills and Employment Training Program: https://www.mnbc.ca/directory/view/342-ministry-of-employment-training ↵

- Métis Bibliography: http://solr.bccampus.ca:8001/bcc/file/c0a932f4-8d79-4d3d-a5d4-3f8c128c0236/1/FINAL%20Metis%20Bibliography%20for%20Indigenization%20Guides%202017.pdf ↵

Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Being

While there is great diversity among Indigenous Peoples, there are also some commonalities in Indigenous worldviews and ways of being. Indigenous worldviews see the whole person (physical, emotional, spiritual, and intellectual) as interconnected to land and in relationship to others (family, communities, nations). This is called a holistic or wholistic view, which is an important aspect of supporting Indigenous students. The Canadian Council of Learning produced State of Aboriginal Learning in Canada: A holistic approach to measuring success [PDF][1] to support diversity of Indigenous knowledges from First Nations, Métis, and Inuit perspectives. Across all three of these perspectives, relationships and connections guide the work of supporting Indigenous students.

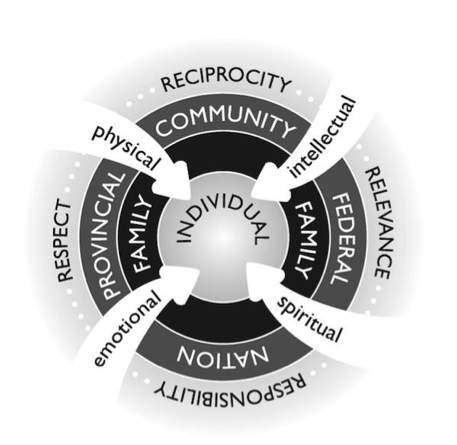

The Indigenous wholistic framework[2] (Figure 2.2 below) illustrates Indigenous values and ways of being and the direct relationship and connection between academic programs and students services in supporting Indigenous students. Kirkness and Barnhardt (1991) first provided post-secondary institutions with the 4Rs to supporting Indigenous students: respecting Indigenous knowledge, responsible relationships, reciprocity, and relevance. This was further elaborated by Pidgeon with the Indigenous wholistic framework, which is just one of many models that have been used to think about the wholistic student experience, particularly Indigenous student success (Pidgeon, 2012, 2016a). This framework is not meant to be a model that treats all Indigenous Peoples as the same but a model to show how the diversity of Indigenous understandings of place, language, and cultures relates to the individual, faculty, and community, both institutional and Indigenous communities within and outside the institution. An Indigenous learner who is balanced in all realms (physical, intellectual, spiritual, emotional) and empowered in terms of who they are as an Indigenous person has their cultural integrity (Tierney & Jun, 2011) not only valued but honoured as they go through their post-secondary journey.

This Indigenous wholistic framework provides guiding principles to ensure post-secondary institutions become accessible, inclusive, safe, and successful places for Indigenous students as follows:

Respect

- Encompasses an understanding of and practicing community protocols.

- Honours Indigenous knowledges and ways of being.

- Considers in a reflective and non-judgmental way what is being seen and heard.

Responsibility

- Is inclusive of students, the institution, and Indigenous communities; also recognizes one’s own connections to various communities.

- Continually seeks to develop and sustain credible relationships with Indigenous communities. It’s important to be seen in the community as both a supporter and a representative of the institution.

- Means understanding the potential impact of one’s motives and intentions on oneself and the community.

- Honours that the integrity of Indigenous people and Indigenous communities must not be undermined or disrespected when working with Indigenous people.

Relevance

- Ensures that curricula, services, and programs are responsive to the needs identified by Indigenous students and communities.

- Involves Indigenous communities in the designing of academic curriculum and student services across the institution to ensure Indigenous knowledge is valued and that the curriculum have culturally appropriate outcomes and assessments.

- Centres meaningful and sustainable community engagement.

Reciprocity

- Shares knowledge throughout the entire educational process; staff create interdepartmental learning and succession planning between colleagues to ensure practices and knowledge are continued. Shared learning embodies the principle of reciprocity.

- Means Indigenous and non-Indigenous people are both learning in process together. Within an educational setting, this may mean staff to student; student to student, faculty to staff; each of these relationships honours the knowledge and gifts that each person brings to the classroom, workplace, and institution.

- Results in all involved within the institution, including the broader Indigenous communities, gain experience in sharing knowledge in a respectful way.

- Views all participants as students and teachers in the process.

Through this model, front-line staff, advisors, and student services professionals can begin to see the depth and breadth of relationships to support the whole student.

Media Attributions

- Fig 2.2: Indigenous wholistic framework © M. Pidgeon is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- State of Aboriginal Learning in Canada: A holistic approach to measuring success: http://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/education2/state_of_aboriginal_learning_in_canada-final_report,_ccl,_2009.pdf ↵

- Pidgeon intentionally uses the “w” in holistic for the Indigenous wholistic framework to reference the whole person. Absolon (2009) and Archibald et al. (1995) also intentionally use the term “wholistic.” ↵

Summary

Sharing the 4Rs as key principles in the Indigenous wholistic framework shows the heart of Indigenous education in that it connects the physical, emotional, spiritual, and intellectual realms of a student to their families, their campus community, their Indigenous communities, and beyond. Awareness of student diversity is decolonizing and debunks popular misconceptions and stereotypes about Indigenous Peoples. This awareness helps lessen the potential for microaggressions, thus creating a culturally safe environment for student success. The following activities are self-reflective and let you compare current ethical practices to Indigenizing your practice.

Activities

Activity 1: Building a wholistic practice

Type: Individual

Time: 1 hour

Looking at the Indigenous wholistic framework and the guiding principles, reflect on the following questions:

- How can you use the 4 Rs (respect, relevance, reciprocity, and responsibility) to better serve and honour the culture of Indigenous students?

- How do you see the physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual needs of Indigenous students and communities being helped (or hindered) at your institution?

- What areas of growth and development can you identify for yourself?

- What ways can you further your professional development? (Who can you turn to for support?

- What resources do you need? What books, workshops, online guides, or communities of practice can help you to gain this knowledge?)

- What aspect of the whole student to do you engage in your practice? How could you engage with the other aspects?

Activity 2: Dispelling stereotypes and addressing microaggressive behaviours

Type: Individual

Time: 1 hour

Watch the two-minute video Wab Kinew Top 5 Stereotypes toward Indigenous Peoples in Canada[1]

Read:

- Lenard Monkman CBC News (2016) “Debunking the myth that all First Nations people receive free post-secondary education.”[2]

- Heather Shotton (2017). “I Thought You’d Call Her White Feather”: Native Women and Racial Microaggressions in Doctoral Education.[3] Journal of American Indian Education, 56(1), 32-54. (Note: you’ll need a JStor institutional account to download this article.)

Questions:

- What are three new ideas about Indigenous student experiences that you have gained from reading the resources and watching the videos?

- What else do you need to know?

- How will you go about to seek answers to these questions?

Activity 3: Working in a culture of support

Type: Group

Time: 1 hour

- Discuss how you would create a culture of support where you can challenge assumptions and biases in the work of your unit.

- Build examples of promising practices at your institution that can help your unit further serve Indigenous students. Consider campus environments, spaces, and cultures; policies; programs; websites; curricula; pedagogies; academic programs; and student services.

- Read the ACPA Ethical Principles and Standards [PDF][4] and create an ethical code of conduct for working with Indigenous students in your unit or program.

- Once your team or unit has developed some ideas on how it can create a culture of support, develop a strategy for sharing reflections on how well you are living up to this ideal, both individually and as a group. Discuss ways you can hold each other accountable for meeting this goal.

Attribution:

“Pulling Together: A Guide for Front-Line Staff, Student Services, and Advisors “ by Ian Cull; Robert L. A. Hancock; Stephanie McKeown; Michelle Pidgeon and Adrienne Vedan is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

References:

-

Wab Kinew Top 5 Stereotypes toward Indigenous Peoples in Canada video: https://youtu.be/20EmLfHTVlw ↵

- “Debunking the myth that all First Nations people receive free post-secondary education http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/debunking-the-myth-that-all-first-nations-people-receive-free-post-secondary-education-1.3414183 ↵

- “I Thought You’d Call Her White Feather”: Native Women and Racial Microaggressions in Doctoral Education: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/jamerindieduc.56.issue-1 ↵

- ACPA Ethical Principles and Standards: http://www.myacpa.org/sites/default/files/Ethical_Principles_Standards.pdf ↵