4.6 Indigenous Approaches & Decolonizing Community Development Practice

Indigenous Approaches

I would like to acknowledge the individuals and organizations that shared their knowledge to help us learn about the history of Indigenous people in Canada. Please bring openness and respect to this learning.

This section will focus on healing that has happened and is happening in Indigenous communities in the context of substance use. Here is what we know: the Canadian Government has systemically and continuously tried to eradicate Indigenous groups across North America, devalued their stories and cultural practices (1). The Canadian Government, under the Indian Act, forced generations of trauma upon individuals and communities; we must acknowledge and understand this as “to understand the Aboriginal perspective there needs to be recognition of the effects of colonization” (2).

Indigenous people are strong and resilient (3). According to McIvor et al. (4), Aboriginal communities have asserted “that their language and culture is at the heart of what makes them unique and what has kept them alive in the face of more than 150 years of colonial rule” (5). By understanding the ways Indigenous communities have responded to colonization and ongoing health concerns in this context, substance use may help non-Indigenous practitioners understand Indigenous practices. Of key importance is the understanding that “health” goes beyond the western ideal of physical and mental health; Indigenous health is “understood as one of a harmonious relationship within the whole person, including mind, body, emotion, and spirit” (6). By knowing and respecting this worldview, Social worker practitioners may begin to explore the ways they can learn from Indigenous communities.

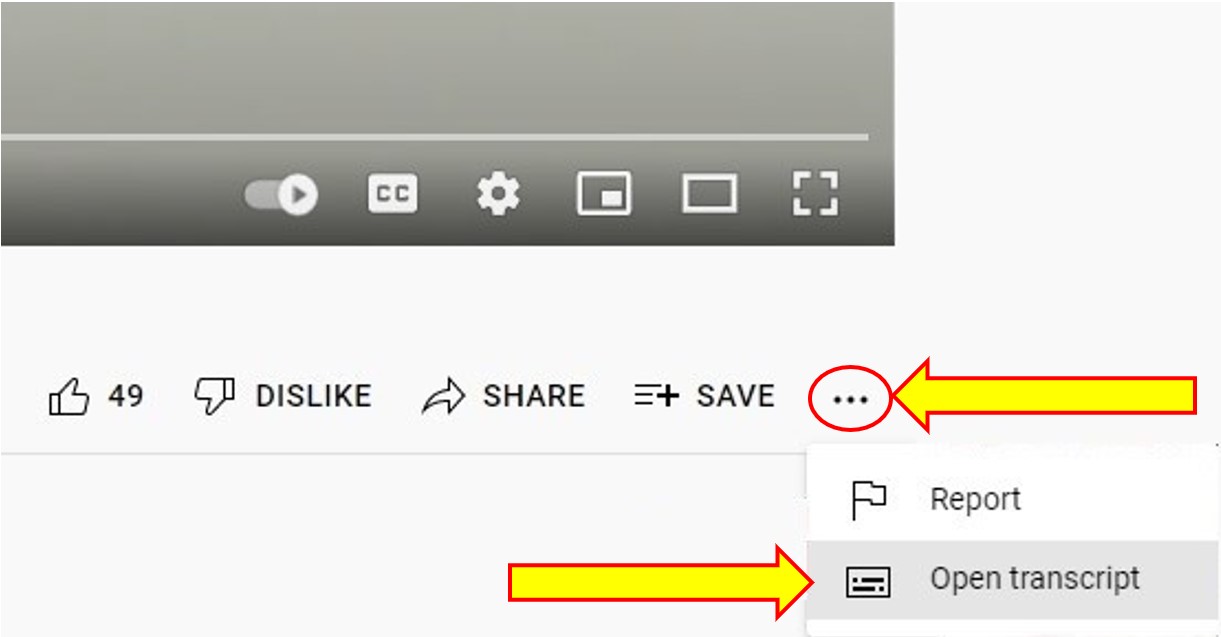

What non-Indigenous Canadians need to know. By TVO Today Docs. Eddy Robinson is an educator on Indigenous issues. In this web series called “First Things First,” Robinson explains why asking “How Can I Help?” is not the right question.(7)

Transcript

Indigenous Canadians who use substances have some of the highest rates of substance use disorders in Canada because of inter-generational trauma and colonization (8). Substance use is not unique to Indigenous groups and many individuals and communities are addressing their substance use using culture as intervention and treatment.

Most Indigenous scholars proposed that the wellness of an Aboriginal community can only be adequately measured from within an Indigenous knowledge framework that is holistic, inclusive, and respectful of the balance between the spiritual, emotional, physical, and social realms of life. (9)

Some groups may solely use culture and traditional methods, some may use Western treatment and sometimes individuals and groups use a blending of the two. This blending could be seen as utilizing a two-eyed seeing approach, a concept developed by Elder Albert Marshall which he suggested one uses the strengths of Indigenous knowledge and the strengths of Western knowledge so one may come to see the world more comprehensively and for the benefit of all (10). Evidence is clear: culture is a foundation of Indigenous health, from prevention initiatives to healing from substance use and trauma (11).

In Nova Scotia, there are some services provided to Indigenous people in Indigenous communities that use a two-eyed seeing approach. For example, Eagle Nest Recovery House in Sipekne’katik First Nation, Nova Scotia provides “best practices and community based culturally relevant programs which are delivered by certified addictions counsellors” (12).

Activities

- Research two-eyed seeing(13)

- How can two-eyed seeing help you as a Social worker?

- Can two-eyed seeing be used beyond an Indigenous lens? How?

- How can you ensure cultural respect/responsiveness when learning about Indigenous treatments?

It is important to reiterate that each Indigenous group in Canada is unique, and not all interventions would be appropriate. The culture-based intervention and healing may include any or all of spirit, ceremonies, language, values and beliefs, stories and songs, land-based activities, food, relations, nature, and history, among others.

For More Information:

The Medicine Wheel

What is a medicine wheel? McCormick (16) provides the following overview of the medicine wheel:

The Aboriginal medicine wheel is perhaps the best representation of an Aboriginal world-view related to healing. The medicine wheel describes the separate dimensions of the self– mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual – as equal and as parts of a larger whole. The medicine wheel represents the balance that exists between all things. Traditional Aboriginal healing incorporates the physical, social, psychological, and spiritual being. (17) (18)

The medicine wheel has many iterations and is used differently by different practitioners as noted by Jeff Ward in the video below(19). It is important to note that the teachings of the medicine wheel can be used as part of a two-eyed seeing approach to health.

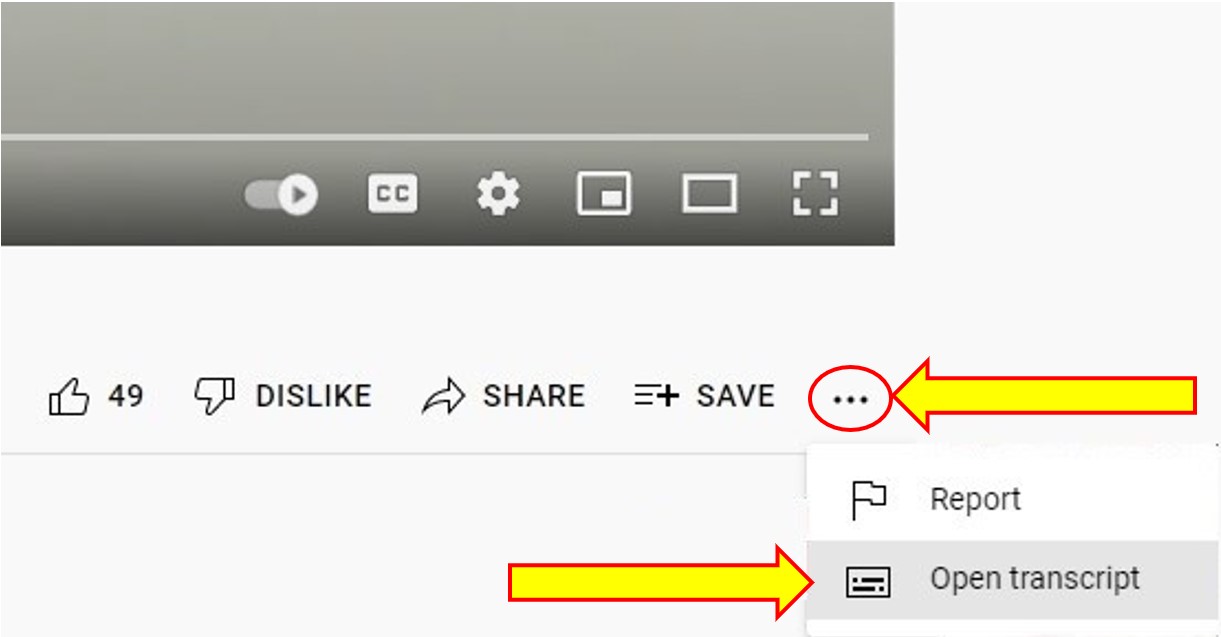

What is the Medicine Wheel? Teachings by Jeff Ward. By The Preservation Project. Jeff Ward, From Membertou, First Nation teaches us some lessons about the Medicine Wheel.(19)

Transcript

Food For Thought

- How can you learn more about medicine wheels?

- Where can you go for culturally appropriate information?

- How can you incorporate the medicine wheel into your life? Your work?

Elders

What is an Elder? The term Elder “refers to someone who has attained a high degree of understanding of First Nation, Métis, or Inuit history, traditional teachings, ceremonies, and healing practices” (20) and is not defined by their age. Elders do not belong to just one family, they are part of the community, and respect should be given to Elders from all, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. Elders have a revered place among Indigenous communities in Canada. “Elders were the carriers of knowledge of both physical and spiritual reality and that they have been educated through the oral tradition” (21). The role of Elders in Indigenous communities cannot be stressed enough. They are the keepers of knowledge and are honoured and respected.

Please watch the video below to deepen your understanding of Elders(22).

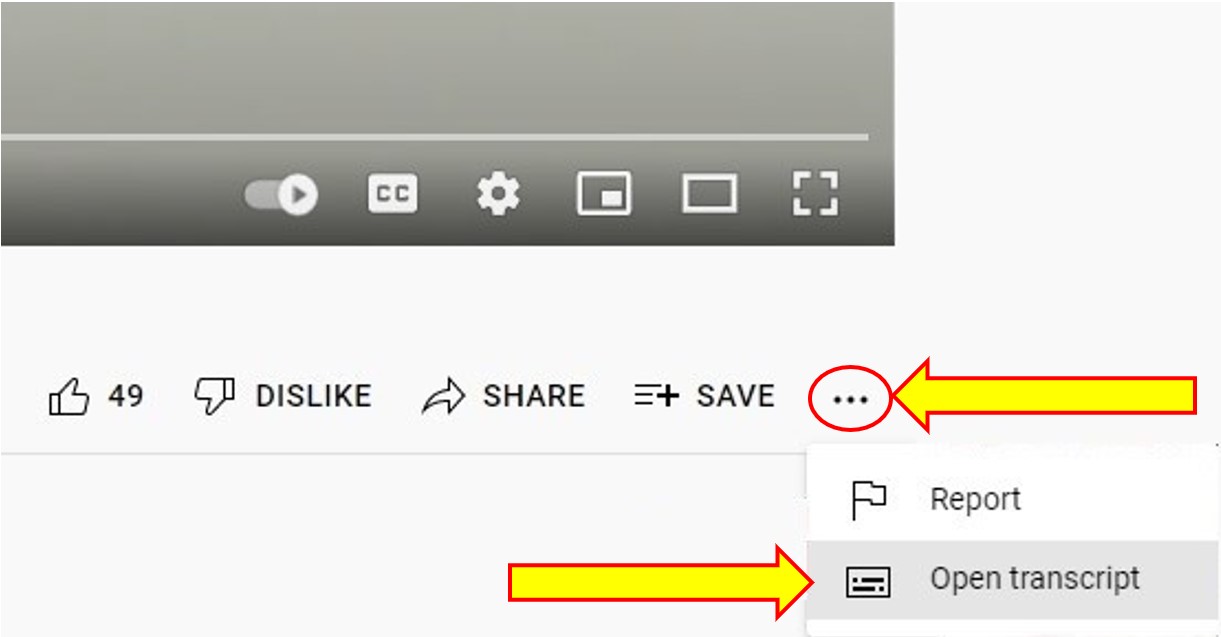

The Elders: Getting to know some of the most honoured members of First Nation. By CBC/Radio-Canada. Elders from Mi’kmaw, Wolastoqi and Peskotomuhkati communities shared their stories for this five-part weekly series.

Transcript

Food For Thought

- What did you learn about Elders?

- What would you like to know more about?

Land based treatment

Nature is a powerful force and how we engage with nature depends on many factors, where we live, access to wilderness, finances, ability, safety and more. One of the social determinants of health is environment; consequently, where we live plays a role in our health. The earth takes care of us, it is where we build our homes, grow/hunt/fish our food, drink our water, and we live, work, and play on the land.

Food For Thought

- Have you ever taken a walk in a forest? A beach? Your neighbourhood?

- What did it feel like? Were you present in this moment?

Taking time to honour the earth is important, and Indigenous communities have a deep sacred relationship with the land, with the earth. The land plays a critical role in substance use treatment for Indigenous people. Carrier Sekani Family Services “offers a land-based healing program that uses culture and the natural environment to encourage its participants to return to their First Nations’ culture to assist in combating addiction (23), Utilizing the land allows a path to healing for communities who have been removed from the land and traditional teaching due to colonization. This type of programming includes both traditional teachings as well as Western interventions, utilizing the concept of two-eyed seeing which honours the best of Indigenous and non-Indigenous treatment philosophies and interventions.

READ

The Carrier Sekani Family Services Addictions Recovery Program wepage for an example of a First Nations approach to addiction recovery(23).

Smudging

What is smudging? The smoke from burning sweet grass, cedar, or sage, is brushed toward one’s body to cleanse the spirit. The smudging is usually done before a person involves themselves in a traditional ceremony (24).

Watch The Seven Sacred Teachings with Dr. Lottie Johnson via Vimeo.

LISTEN

Did you know that NSCC has smudging rooms on all of the campuses? NSCC establishes smudging rooms at all campuses via CBC NS.

Food For Thought

Watch the CBC news video: NSCC establishes smudging rooms at all campuses

-

- Did you know that NSCC has smudging rooms on all of the campuses?

- Have you ever seen smudging?

- Have you ever participated in a smudge?

- What did that feel like?

Sharing circles have an important role in Indigenous healing. They are “an Indigenous method used to explore a topic (e.g. health) and co-create solutions (e.g. how to restore balance) in a safe and protected space where each individual’s thoughts, experiences, feelings and ideas are respected”.(25)

READ:

To learn more about sharing circles read Sharing Circles by a blog post by Raven on her Silence of the Season website.

Drumming

Excerpt from “Interview with Morning Star River Singers” November 7, 2004, Toronto, ON(26)

The drum is circular; Mother Earth is circular and that’s what that drum represents. It represents Mother Earth. When the singers sound the drum that is the heartbeat of Mother Earth and we give thanks for everything that she gives us. She has been taking care of us from the beginning of time, taking care of us with food, water, medicine, everything. She has never turned her back on us. So when the singers are sounding that drum and the dancers are coming around that drum, they are dancing in time with that drum to show that connection to her. While they are dancing they are thinking about those things that Mother Earth provides for us, but as well they are thinking about all their friends and family that have helped them along the way in their life. Every one of us has been through trying times and we needed our relatives for support. We need our friends for support and they’ve been there for us no matter how down we have been; they have been there for us. So we need to acknowledge and remember all those people because that drum there represents life, represents all of the seasons, represents all of those things – like the medicine wheel teachings on that drum.

Brian Knockwood of Sipekne’katik First Nation is a local drum maker who has been making drums for more than two decades.

READ

Learn more about Brian and how he uses drumming in his work as a substance use counsellor.

Activities

- Choose one of the following films about Indigenous drumming.

- What stood out for you? Why?

- Have you ever experienced drumming?

- What about taking photographs when people are drumming?

- When does drumming happen?

- Can anyone participate in drumming?

- How does drumming help heal?

Substance use treatment centres for First Nations and Inuit

First Nations communities with problematic substance use challenges have access to services funded by the Government of Canada.

For information on residential treatment programs, contact a treatment centre near you. You can also contact your local regional office at the number provided below.

For information on community-based prevention programs, contact your community nursing station, health centre, band council or local regional office.

Attribution

Exploring Substance Use in Canada by Julie Crouse is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Changes include adding material.

WHAT IS DECOLONIZATION? WHY DOES IT MATTER?

TOPICS:

- What Is Decolonization? Why Does It Matter?

- Indigenization

Pulling Together: A Guide for Front-Line Staff, Student Services, and Advisors by Ian Cull; Robert L. A. Hancock; Stephanie McKeown; Michelle Pidgeon; and Adrienne Vedan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

If we want to challenge social injustice and contribute to systemic change, we need to understand and integrate concepts of decolonization and Indigenization in community practice in an intentional and ongoing way.

Decolonization is the process of deconstructing colonial ideologies that claim the superiority and privilege of Western thought and approaches (Cull et al., 2018). On the one hand, decolonization involves dismantling structures that perpetuate the status quo and address unbalanced power dynamics. On the other hand, decolonization involves valuing and revitalizing Indigenous knowledges and approaches, and challenging settler biases and assumptions that have impacted Indigenous ways of being (Cull et al., 2018).

“Decolonization doesn’t have a synonym” (Tuck & Yang, 2012, p. 3). While unquestionably connected to human rights and social justice, it is not a substitute for these concepts (Ritskes, 2012). Specifically, decolonizing demands a centering of Indigenous ways of knowing and being, Indigenous Land, and Indigenous sovereignty.

Video: DECOLONIZED EDUCATION EXPLAINED IN SIMPLE TERMS

Source: YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xestqqmz600

The physical and mental aspects of decolonization apply equally to Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities (Gray, Coates, Yellow Bird, & Hetherington, 2016).

For non-Indigenous people, decolonization is the process of critically examining your beliefs about Indigenous Peoples and cultures by learning about yourself in relationship to the Land and communities where you live and the people with whom you interact.

We work in systems that perpetuate colonial ideals and privilege Western ways of being and doing. For example, many community services use forms and procedures instead of first initiating relationships with community members. This is a colonial process that tends to create environments of exclusion rather than inclusion.

Q – What other community practices and approaches can you think of that are rooted in colonial ways of thinking and doing?

Decolonization is an ongoing process that requires all of us to be collectively involved and responsible. Decolonizing our institutions means we create spaces that are inclusive, respectful, and honour Indigenous Peoples.

(Adapted from Decolonization and Indigenization)

Video: Ted Talk – Decolonization is for Everyone

SOURCE: YOUTUBE, HTTPS://YOUTU.BE/QP9X1NNCWNY

INDIGENIZATION

Pulling Together: A Guide for Front-Line Staff, Student Services, and Advisors by Ian Cull; Robert L. A. Hancock; Stephanie McKeown; Michelle Pidgeon; and Adrienne Vedan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Indigenization is a collaborative process of naturalizing Indigenous intent, interactions, and processes and making them evident to transform spaces, places, and hearts. In the context of community development practice, this involves including Indigenous perspectives and approaches to the benefit of all community members (Cull et al., 2018)

Indigenization seeks a fundamental shift in the ways that communities:

- Include Indigenous perspectives, values, and cultural understandings in daily practices

- Position Indigenous ways of knowing at the heart of community development work

- Integrate cultural protocols and practices in the operations of our organizations

Indigenization values sustainable and respectful relationships with First Nation, Métis, and Inuit communities, Elders, and organizations. When Indigenization is practiced at the community level, Indigenous Peoples see themselves represented, respected, and valued and all community members benefit. We all gain a richer understanding of the world and of our specific location in the world through an awareness of Indigenous knowledges and perspectives. Indigenization also contributes to a more just world, creating a shared understanding that opens the way toward reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. It also counters the impacts of colonization by upending a system of thinking that has typically discounted Indigenous knowledge and history.

Indigenization, like decolonization, is an ongoing process, one that will shape and evolve over time.

Starting With Ourselves: Good Intentions Are Not Enough

Good intentions are not enough for community development work. Our work must be grounded in anti-oppressive, anti-racist, and decolonizing practices and relations; otherwise, we risk repeating harmful mistakes of the past.

It is our responsibility to question the ways in which we show up in communities, the space we take up, the power and privilege we have been afforded, and how we (knowingly or unknowingly) perpetuate systemic oppressions and settler-colonialism while engaged in community work.

Reflection Questions:

If you are a settler on this Land, it is your responsibility to reflect on how you have benefitted (and continue to benefit from) the ongoing devastation and genocide of Indigenous Peoples as a result of colonialism. How have you been complicit in upholding these colonial systems of oppression? Who are you accountable to?

A Shift In Perspective and Power

Indigenous Worldviews on working with communities are valuable for all community and social service workers. Decolonizing our practice requires an ongoing commitment to learning and unlearning; to critical thinking; and to inviting uncomfortable questions that interrogate and challenge accepted knowledge and ways of thinking.

Decolonizing community practice requires an intentional shift in perspective and power from working for a community to working with a community.

“If you come here to help me, you’re wasting your time. If you come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” – Lilla Watson

As outlined in the Seven Sacred Teachings, the value of humility is critical in reminding us that we are merely one small piece of the bigger puzzle. Nobody is an expert on other people’s lives. Adopting a stance of “not-knowing”, humility, openness, and curiosity, together with a willingness to be held accountable by the communities we serve, are key ingredients for this work.

Change does not happen overnight. Social change takes intentional, ongoing, consistent actions from individuals, groups, and communities. We must look to – and listen to – Indigenous Peoples throughout the process.

Taking Action

We would like to acknowledge that this resource would not have been possible without the work of Indigenous scholars, who have been researching and writing in this field for decades.

When learning about settler colonialism and working in communities:

- Do not act out of guilt, but rather out of a genuine interest in challenging the larger oppressive power structures.

- Understand that [you] are secondary to the Indigenous Peoples that [you] are working with and that [you] seek to serve. [You] and [your] needs must take a back seat;

– Lynn Gehl, “My Ally Bill of Responsibilities.” - Accept that you will make mistakes and upset people as you learn.

- Take responsibility for your own learning. Where do you live? Whose Land are you on? Are you on unceded Land? Are you on Treaty Land? Learn what your responsibilities are and how you can act in solidarity with Indigenous Peoples in your community.

Some preliminary steps for settlers in decolonizing community development practice can be found here at the Community Development Learning Initiative.

To get started with your (un)learning journey, check out this database of anti-racism and decolonization resources.

KEY TAKEAWAYS AND FEEDBACK

We want to learn your key takeaways and feedback on this chapter.

Your participation is highly appreciated. It will help us to enhance the quality of Community Development Practice and connect with you to offer support. To write your feedback, please click on Your Feedback Matters.

Thank you!

Attribution:

Community Development Practice: From Canadian and Global Perspectives by Sama Bassidj, MSW, RSW is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

REFERENCES

- Smith, M. (2021). Things transformed: Inalienability, Indigenous storytelling, and the quest to recover from addiction. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 39(2), 160-174. https://doi-org.libproxy.stfx.ca/10.1080/07347324.2020.1776183

- MacKenzie, B., & Morrissette, V. (2002). Social work practice with Canadians of Aboriginal background: Guidelines for respectful social work. In J. R. Graham & A. Al-Krenawi (Eds.), Multicultural social work in Canada: Working with diverse ethno-racial communities (pp. 251-279). Oxford University Press.

- Kirmayer, L. J., Dandeneau, S., Marshall, E. Kahentonni Phillips, M., & Williamson, K. J. (2011). Rethinking resilience from Indigenous perspectives. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(4), 84–91. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/070674371105600203

- McIvor, O., Napoleon, A., & Dickie, K. (2009). Language and culture as protective factors for at-risk communities. Journal of Aboriginal Health, 5, 6-25. https://doi.org/10.18357\/ijih51200912327

- Ibid, p. 6

- Rowan, M., Poole, N., Shea, B., Gone, J. P., Mykota, D., Farag, M., Hopkins, C., Hall, L., Mushquash, C., & Dell, C. (2014). Cultural interventions to treat addictions in Indigenous populations: Findings from a scoping study. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention and Policy, 9, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-9-34

- Two Docs. (2019, April 2). What non Indigenous Canadians need to know. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b1E-3Hb1-WA

- Niccols, A., Dell, C. A., & Clarke, S. (2010). Treatment issues for Aboriginal mothers with substance use problems and their children. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 8(2), 320–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-009-9255-8

- Marsh, T. N., Coholic, D., Cote-Meek, S., & Najavits, L. (2015). Blending Aboriginal and Western healing methods to treat intergenerational trauma with substance use disorder in Aboriginal peoples who live in Northeastern Ontario, Canada. Harm Reduction Journal, 12(14). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-015-0046-1

- Institute for Integrative Science and Health. (n.d.) Guiding principles (Two-eyed seeing). http://www.integrativescience.ca/Principles/TwoEyedSeeing/

- Chong, J., Fortier, Y., & Morris, T. L. (2009). Cultural practices and spiritual development for women in a Native American alcohol and drug treatment program. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 8(3), 261–282. https://doi-org.libproxy.stfx.ca/10.1080/15332640903110450

- Native Alcohol and Drug Abuse Counselling Association of Nova Scotia. (2021). Eagle Nest Recovery, (para.1). http://www.nadaca.ca/in-patient-treatment-centres/eagles-nest/

- Guiding Principles (Two Eyed Seeing) | Integrative Science. (n.d.). http://www.integrativescience.ca/Principles/TwoEyedSeeing/

- Traditional Wellness and Healing. (n.d.-c). https://www.fnha.ca/what-we-do/health-system/traditional-wellness-and-healing

- What is Cultural Competency? – AFN It’s Our Time Toolkit. (n.d.). AFN It’s Our Time Toolkit – AFN Toolkit. https://education.afn.ca/afntoolkit/web-modules/plain-talk-8-cultural-competency/what-is-cultural-competency/

- McCormick, R. (2009). Aboriginal approaches to counselling. In L. Kirmayer & G. Valaskakis (Eds.), Healing traditions: The mental health of aboriginal peoples in Canada (pp. 337–354). UBC Press.

- Kirmayer, L. J., Dandeneau, S., Marshall, E. Kahentonni Phillips, M., & Williamson, K. J. (2011). Rethinking resilience from Indigenous perspectives. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(4), 84–91. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/070674371105600203

- McCormick, R. (2009). Aboriginal approaches to counselling. In L. Kirmayer & G. Valaskakis (Eds.), Healing traditions: The mental health of aboriginal peoples in Canada (pp. 337–354). UBC Press.

- The Preservation Project. (2019, July 15). What is the Medicine Wheel? Teachings by Jeff Ward. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bSw0s8rcuSg

- University of Toronto. (2019, Jan. 4). Elders (para. 1). https://www.oise.utoronto.ca/deepeningknowledge/Teacher_Resources/Curriculum_Resources_(by_subjects)/Social_Sciences_and_Humanities/Elders.html

- Marsh, T. N., Coholic, D., Cote-Meek, S., & Najavits, L. (2015). Blending Aboriginal and Western healing methods to treat intergenerational trauma with substance use disorder in Aboriginal peoples who live in Northeastern Ontario, Canada. Harm Reduction Journal, 12(14). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-015-0046-1

- CBC News. (2021, June, 21). The Elders: Getting to know some of the most honoured members of First Nation communities. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zhVnWwzzeRE

- Carrier Sekani Family Services. (2021). Addictions recovery program, (para. 5). https://www.csfs.org/services/addictions-recovery-program

- Cape Breton University. (2021). Oral histories. https://www.cbu.ca/indigenous-affairs/mikmaq-resource-centre/mikmaq-resource-guide/essays/oral-histories/

- Rothe J. P., Ozegovic, D., & Carroll L. J. (2009). Innovation in qualitative interviews: “Sharing Circles” in a First Nations community. Injury Prevention: Journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention, 15, 334-340. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1780953722?pq-origsite=primo&accountid=13803

- Transcript from the video interview is reproduced in the document: Government of Nova Scotia. (2021). Explore music 8: Voices of the drum. https://curriculum.novascotia.ca/sites/default/files/documents/resource-files/Explore%20Music%208%20Voices%20of%20the%20Drum.pdf

- Perley, L. (2020, January 27). The healing powers of a hand drum. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/brian-knockwood-wabanaki-drum-maker-1.5391447

- National Film Board of Canada. (2007). First Stories – His Guidance (Okiskinotahewewin). https://www.nfb.ca/film/first_stories_his_guidance_okiskinotahewewin/

- National Film Board of Canada. (1987). Poundmaker’s Lodge: A Healing Place. https://www.nfb.ca/film/poundmakers_lodge_healing_place/

Cull, I., Hancock, R., McKeown, S., Pidgeon, M., & Vedan, A. (2018). Pulling Together: A Guide for Front-Line Staff, Student Services, and Advisors. https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationfrontlineworkers/

Ritskes, E. (2012). What is Decolonization and Why Does It Matter? https://intercontinentalcry.org/what-is-decolonization-and-why-does-it-matter/

Gray, M., Coates, J., Yellow Bird, M., & Hetherington, T. (2016). In Gray M. (Ed.), Decolonizing social work. Ashgate Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315576206

Tuck, E. & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1-40.