6 Decolonization and Development

Ian Muldong; Tate Chevolleau; and Ekta Vaghela

Introduction

The term colonialism is defined as “Control by one power over a dependent area or people.” It occurs when one nation invades another, abuses its citizens, and frequently imposes its own cultural norms and language (Blakemore, 2019).

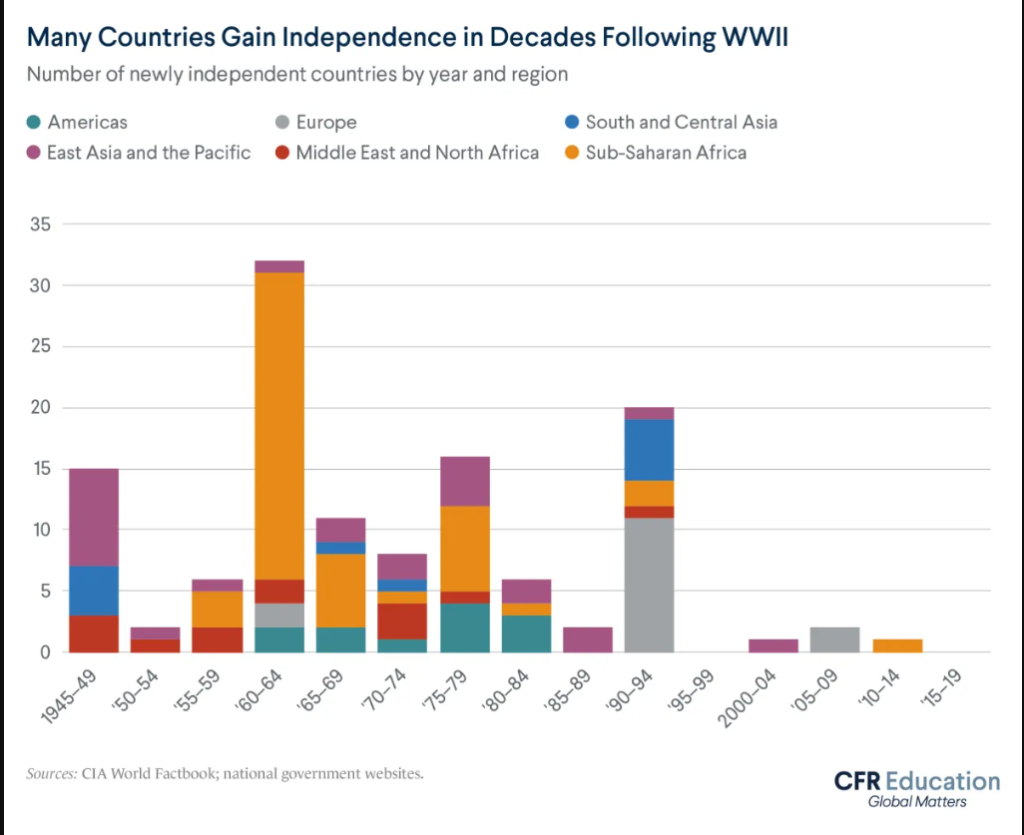

After the Cold War, in 1945, the phrase “third world” was created to describe underdeveloped areas including Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America. In the second half of the twentieth century, non-Western, anti-imperialist, and anti-racist nations that had gained independence from colonial authority and collaborated to fight Cold War alignment began to be known as the Third World, according to Cindy Ewing (2019). Colonialism was pervasive and long-lasting. For instance, more than 80% of the world’s surface was occupied by European empires between 1492 and 1914. Even though many American colonies gained freedom in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a considerable chunk of Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and the Pacific were remained under the sovereignty of the United States, Japan, and Europe in the early twentieth century. However, Third World leaders occasionally split apart along the lines of the greater superpower competition, regional or sectarian conflicts, and diverse objectives for the global order, making it difficult for them to retain their transnational solidarity or the global order.

For example, in order to create the independent nation of Bangladesh, the Bengali-speaking part of Pakistan, which defined itself primarily in terms of religion and came under the influence of military forces, seceded in 1971. India, a secular republic with a 90% Hindu population, inherited a larger amount of industrial and educational resources and was able to retain unity despite the linguistic diversity of its population.

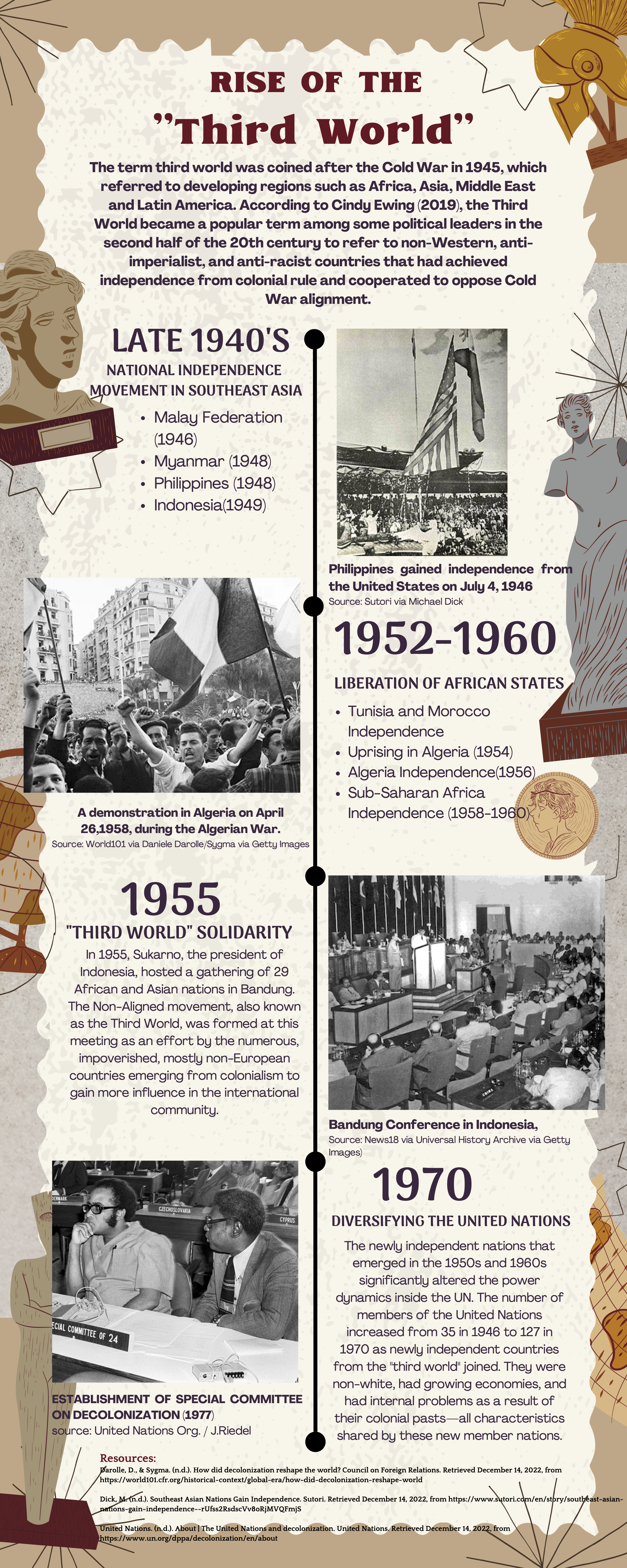

During World War II, the Japanese defeated the British, French, and Dutch armies, giving Southeast Asia a blueprint for how an Asian nation might fight off European oppressors. Following World War II, nationalist movements led to the independence of the Malay Federation (1949), Indonesia (1949), and the Philippines (1948). (1946.)

In the aftermath of World War II, the French government was enthusiastic about maintaining Algeria, which had a substantial French settler population, vineyards, oil and gas deposits, but they granted Tunisia and Morocco their independence between 1952 and 1956. A rebellion in Algeria that started in 1954 was ruthlessly put down by both sides. Nonetheless, the French departed, and Algeria obtained independence in 1962.

African leaders in the French colonies in sub-Saharan Africa were cautious to demand independence because they recognized the importance of the massive French public investment, which totaled billions of dollars, and because they were aware that some of the colonies had gloomy economic prospects. However, the French colonies reclaimed their independence between 1958 and 1960. Decolonization in Africa also frequently featured battles because people of European heritage fought against native Africans in an effort to preserve their personal privileges, control over resources, and political authority.

The new nations also had to deal with important issues in education, such as which language to teach, how to foster a sense of national unity in areas where it was lacking, and how to find rewarding employment for graduates. Rarely were the new countries able to overcome these obstacles, and many of them—even successful ones like South Korea—decided to adopt authoritarian governments.

In 1955, Sukarno—first president of Indonesia—hosted a meeting for twenty-nine African and Asian countries in Bandung which led to the non-aligned movement also known as the Third World. Members of the movement mostly consisted of non-European countries which came from colonialism thus the members sought to gather influence in the international community scene.

The leaders of the so-called Third World countries preferred the name “nonaligned,” but the West did not take it seriously because the movement included communist countries like China and Yugoslavia and was supported by the Soviet Union. The leaders of the movement mostly employed non-alignment as a tactic to secure finance and backing from one or both superpowers.

The newly independent nations that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s significantly altered the power dynamics inside the United Nations (UN). The number of members of the UN increased from thirty-five in 1946 to 127 in 1970 as newly independent countries from the “Third World” joined. They were non-white, had growing economies, and had internal problems as a result of their colonial pasts—all characteristics shared by these new member nations. Due to these circumstances, they periodically clashed with European countries and were skeptical of the political systems, philosophies, and economic institutions that were prevalent on the continent. Additionally, these countries aggressively pushed for the continuance of decolonization, which caused the UN Assembly to routinely take precedence over the Security Council in discussions about self-governance and decolonization. The new countries showed that the colonial age was ending in the eyes of the international world by forcing the UN to adopt resolutions for independence for colonial states and form a special committee on colonialism, even if some countries continued to fight for independence.

The process of postwar decolonization came about as the result of rising liberation movements across the world, as well as competition for global dominance between the Soviet Union and the United States. This period is important because it led to the establishment of organizations like North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the UN, as well as increased foreign intervention and military aid in what would come to be known as third world countries—Guatemala, Korea, Palestine, Algeria, etc. Competing Soviet and American interests led to political violence and separation of territory in places like Korea, and long-term destabilization of government and social services in much of Latin America, Asia, and Africa.

In application to community development work, it is important to understand how the global decolonization efforts of the postwar era impact modern social divisions and systemic inequity. When analyzing the formation of the United Nations, and the ideologically and economically driven efforts toward “decolonization” by global superpowers, we can see on a macro scale the impacts of a “top down” development approach. On this broad scale, colonial values and systems of governance remained in place, and were largely rhetorically reframed to garner optimal international support while tangibly working to extract resources—gas, oil, labor, etc.—from nations who were economically powerless in the face of colonial divestment. When we relate this to local community development work we can see how, no matter the scale, no true liberation can be achieved without true social power and citizen control for the most marginalized and historically disenfranchised members of society.

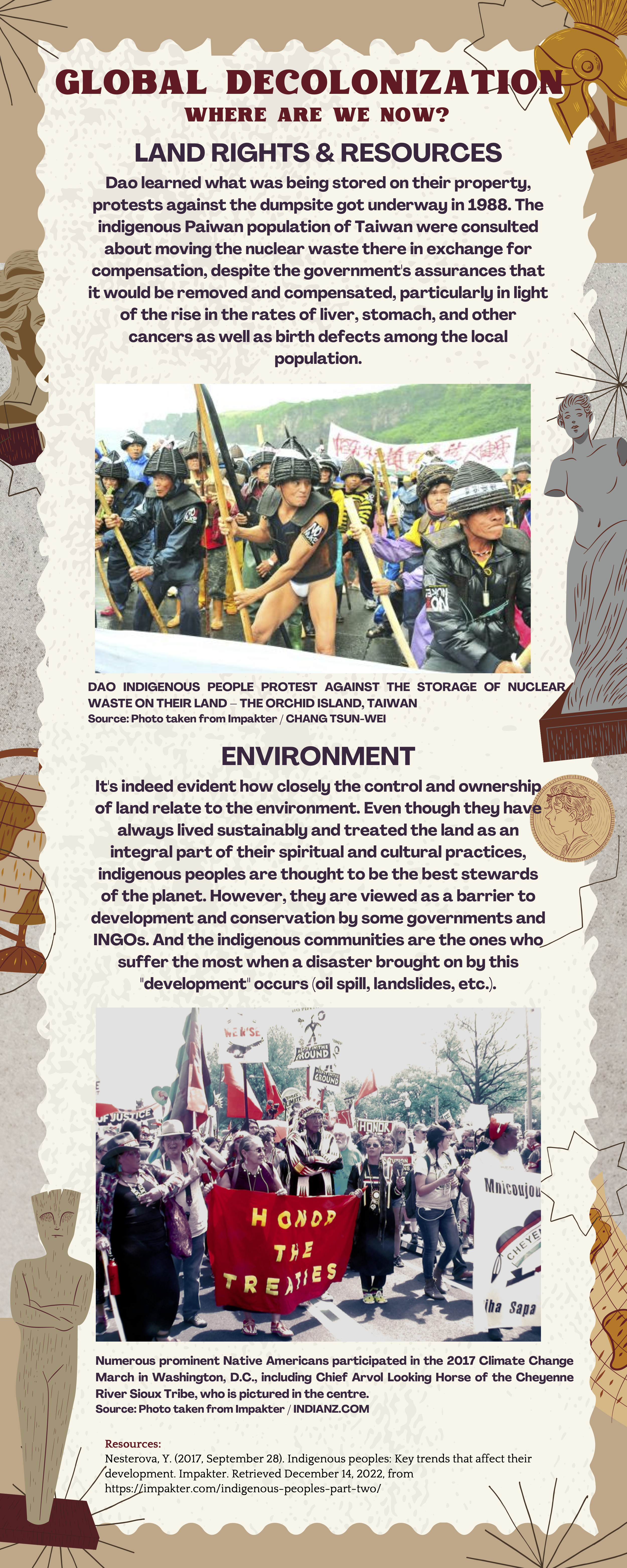

Land Rights & Resources

Dao learned what was being stored on their property, and protests against the dumpsite got underway in 1988. The Indigenous Paiwan population of Taiwan were consulted about moving the nuclear waste there in exchange for compensation, despite the government’s assurances that it would be removed and compensated, particularly in light of the rise in the rates of liver, stomach, and other cancers as well as birth defects among the local population.

Environment

It is indeed evident how closely the control and ownership of land relate to the environment. Even though they have always lived sustainably and treated the land as an integral part of their spiritual and cultural practices, Indigenous peoples are thought to be the best stewards of the planet. However, they are viewed as a barrier to development and conservation by some governments and International non-governmental organizations (INGOs). Indigenous communities are the ones who suffer the most when a disaster brought on by this “development” occurs—oil spill, landslides, etc.

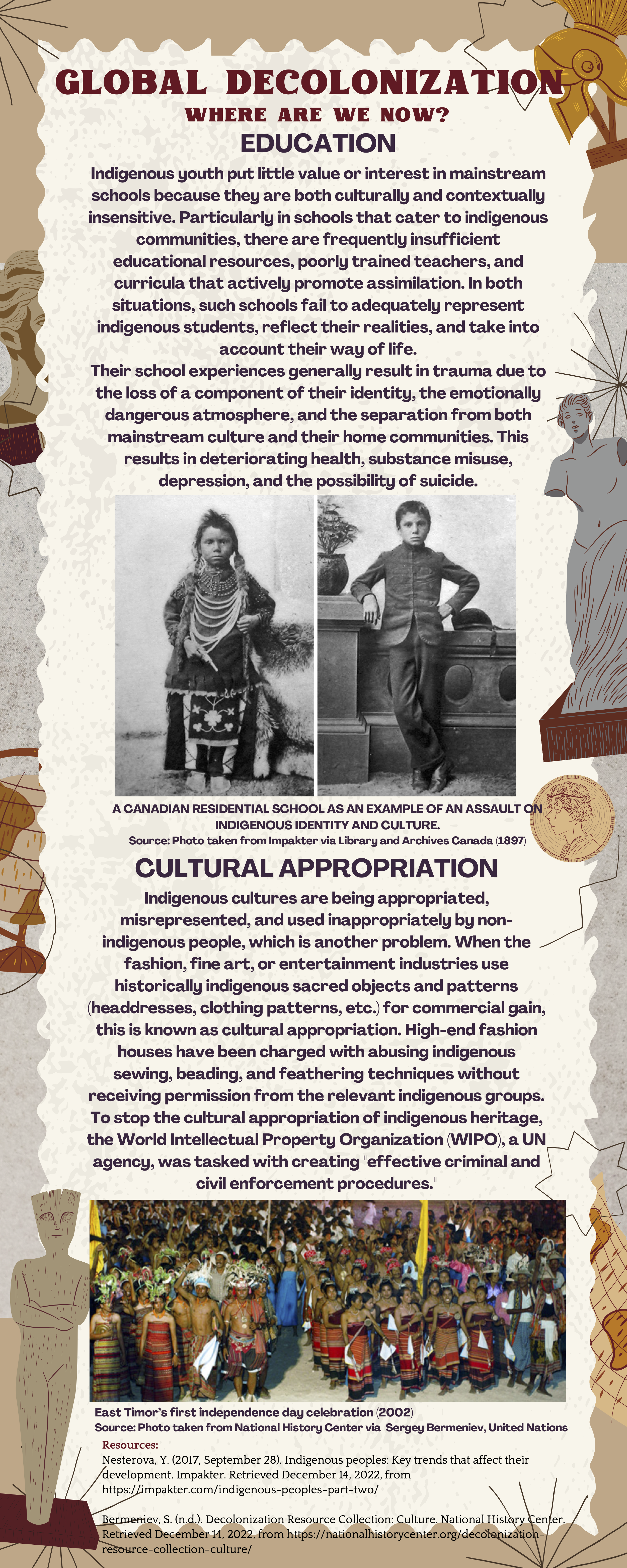

Education

Indigenous youth put little value or interest in mainstream schools because they are both culturally and contextually insensitive. Particularly in schools that cater to Indigenous communities, there are frequently insufficient educational resources, poorly trained teachers, and curricula that actively promote assimilation. In both situations, such schools fail to adequately represent Indigenous students, reflect their realities, and take into account their way of life.

Their school experiences generally result in trauma due to the loss of a component of their identity, the emotionally dangerous atmosphere, and the separation from both mainstream culture and their home communities. This results in deteriorating health, substance misuse, depression, and the possibility of suicide.

Cultural Appropriation

Indigenous cultures are being appropriated, misrepresented, and used inappropriately by non-Indigenous people, which is another problem. When the fashion, fine art, or entertainment industries use historically Indigenous sacred objects and patterns—headdresses, clothing patterns, etc.—for commercial gain, this is known as cultural appropriation. High-end fashion houses have been charged with abusing Indigenous sewing, beading, and feathering techniques without receiving permission from the relevant Indigenous groups.

To stop the cultural appropriation of Indigenous heritage, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), a UN agency, was tasked with creating “effective criminal and civil enforcement procedures.”

Reflective Questions

- Do you know of any communities affected by colonization in your country? How have they resisted?

- Do you think postwar decolonization efforts were effective? Why or why not?

- How do you feel decolonization efforts of the postwar era impact modern social divisions?

Disclaimer

Please note the infographics featured in this chapter are student-created projects and as such include copyrighted material. This work is intended for education purposes and utilizes materials under the guidelines of fair dealing. If you have a concern about the copyright in this image please contact mjohnson@centennialcollege.ca.

References

Bassidj, S., & Hasan, M. (2022). Decolonizing Community Development Practice, Community Development Practice: From Canadian and Global Perspectives. Open Library. Retrieved December 6, 2022, from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/communitydevelopmentpractice/chapter/decolonizing-community-development-practice/

Blakemore, E. (2019, February 19). What is colonialism? National Geographic. Retrieved December 11, 2022. from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/colonialism

Bermeniev, S. (n.d.). Decolonization Resource Collection: Culture. National History Center. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://nationalhistorycenter.org/decolonization-resource-collection-culture/

Council on Foreign Relations. (n.d.). How did decolonization reshape the world? World 101. Retrieved December 6, 2022, from https://world101.cfr.org/historical-context/global-era/how-did-decolonization-reshape-world Darolle, D., & Sygma. (n.d.). A demonstration in Algiers on April 26, 1958, during the Algerian War, a conflict between France and Algerian independence movements from 1954 to 1962 [Photograph]. World 101. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://world101.cfr.org/historical-context/global-era/how-did-decolonization-reshape-world

Dick, M. (n.d.). Southeast Asian Nations gain independence. Sutori. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://www.sutori.com/en/story/southeast-asian-nations-gain-independence–rUfss2RsdscVv8oRjMVQFmjS

Ewing, C. (2019, September 30). The Third World and the United States. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. Retrieved December 6, 2022, from https://oxfordre.com/americanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acr efore-9780199329175-e-755

United Nations. (n.d.). United Nations and decolonization. United Nations. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://www.un.org/dppa/decolonization/en/about

U.S. Department of State. (n.d.). Decolonization of Asia and Africa, 1945–1960. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved December 6, 2022, from https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/asia-and-africa