5

Section one: The fundamentals

A)

Exercise 1: Notebook Prompt

Many of you are likely familiar with the concept of “ability inequity,” which the authors of this article define as “an unjust or unfair (a) ‘distribution of access to and protection from abilities generated through human interventions’ or (b) ‘judgment of abilities intrinsic to biological structures such as the human body’.”

However, they go on to identify the following “ability concepts” that are less familiar:

1) ability security (one is able to live a decent life with whatever set of abilities one has)

2) ability identity security (to be able to be at ease with ones abilities)

How prevalent are these forms of security among disabled people you know? Or, if you identify as a disabled person, would you say your social surroundings and community foster and support these kinds of security? Furthermore, while the focus of the article is on Kinesiology programs, it is also important to reflect on how academia in general accommodates for disability. If you feel comfortable answering this question, what has been your experience of postsecondary education to date?

| Question 1 response:

I don’t identify as a “disabled” individual physically, but I have been diagnosed with a Learning Disorder (to which I have an IEP for) as well as ADHD and GAD. These intellectual “disabilities” hinder by ability to do schoolwork, organize tasks and function overall in everyday life. I would say Trent University and the scholastic environment in general does generally accommodate my needs sufficiently. I have more time to write tests, I can receive class notes for lectures, and I get to write assessments in a quiet, unstimulating room. I do want to note, however, that whilst these accommodations are increasing and the school system seems to be broadening its scope in education delivery methods, the traditional model of academia is extremely limiting in its ability to reach and challenge the minds of neurodivergent individuals. For example, I struggle with auditory learning, so attending lectures for three hours at a time and processing complex topics has been historically challenging for me and others. Additionally, as someone who struggles to keep up with a traditional five-course load, prescribing additional readings to support topics I don’t understand in lecture doesn’t enhance my understanding more than it adds increasing stress and confusion to my learning journey. Again, having an increasing number of courses being delivered in a multitude of mediums, and the incorporation of more kinesthetic/visual aids to enhance topic delivery has been extremely helpful for me and other neurodivergent peers. |

Exercise 2: Implicit Bias Test

Did anything surprise you about the results of the test? Please share if you’re comfortable OR comment on the usefulness of these kinds of tests more generally.

| I would rather not share my results of the test. However, I found myself strongly associating “good” with “abled people” and “bad” with “disabled people” when categorizing the pictograms. Unfortunately, this is the bias society has created by strongly catering infrastructure, modern-day industrial systems, academics and educational systems to neuro-normative and non-disabled people. This test revealed the true existence of a bias I and other hold towards disabled people, considering disability to be ultimately a negative phenomenon rather than an opportunity for innovation and modern-day solutions.

|

B) Keywords

Exercise 3:

Add the keyword you contributed to padlet and briefly (50 words max) explain its importance to you.

|

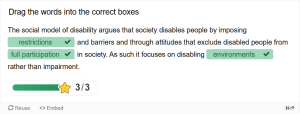

The social model prioritizes the individual as being capable of partaking in aspects of athletics and recreation, on the terms that society is willing and able to accommodate them. The model makes a point of differentiating disability and impairment, which emphasizes capability vs. structural limitations imposed on impaired individuals. The social model analyses the causation of impaired people being unable to participate to the fault of society and its inability to accommodate rather than the fault of the individual for being born different. |

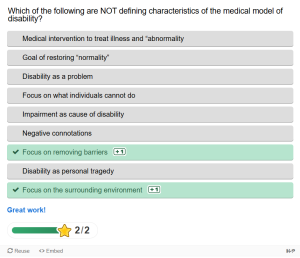

B) On Disability

Exercise 4: Complete the Activities

Exercise 5: Notebook Prompt

What do Fitzgerald and Long identify as barriers to inclusion and how might these apply to sport in particular?

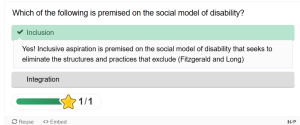

Barriers to inclusion as outlined in the article by Fitzgerald and Long, as discovered by Rankin (2012) include categories of logistical, psychological and physical (Rankin, 2012 as cited in Fitzgerald & Long, 2017). Logistical and physical barriers exclude impaired individuals on an external basis, and include factors such as cost, structural/environmental factors and transportation options (Fitzgerald & Long, 2017). The Arts Council of Northern Ireland (2007) outlined the “invisibility of disability” which relates to the lack of representation of diverse bodies and abilities (Ireland, 2007 as cited in Fitzgerald & Long, 2017). These barriers apply to sport because they project a persona of helplessness and limitation to individuals wanting to partake in sport. Impaired individuals will begin to internalize the ideology that they are the problem, and that the lack of representation on the media is acceptable and simply “the way it is”. This prevents progression of innovative solutions to creating more accessible environments because, by accepting the way our society is currently setup, we refuse to create inclusive change.

C) Inclusion, Integration, Separation

Exercise 6: Complete the Activities

Exercise 7: Notebook Prompt

Choose ONE of the three questions Fitzgerald and Long argue disability sport needs to address and record your thoughts in your Notebook.

- Should sport be grouped by ability or disability?

- Is sport for participation or competition?

- Should sport competitions be integrated?

| Sports are, in my opinion, for participation in a recreational level and competition for an advanced level. For example, entry-level soccer teams are certainly for participation and enhance child development in abilities to socialize, improve endurance and learn how to participate in teamwork. However, as levels advance with age and ability, competition becomes the forefront of the experience if you continue to increase your skill level. However, nobody can reach these competitive levels by first participating at an entry-level where competition is much less important than skill building. Therefore, participation is what I consider the initiation of sports to encompass, whereas competition becomes more prevalent, victory more motivating, as advancement increases. In the instance of disability, competition is just as important and motivating, because at the end of the day, sports are inherently unfair, but defying the odds and creating victorious feat makes these activities all the more exciting. |

Part Two: Making Connections

A) Gender, Sport and Disability

Exercise 8: Complete the Activity

The paradox that sportswomen habitually face (as the authors observe, this isn’t confined to disabled sportswomen) involves the expectation they will be successful in a ‘masculine’ environment while complying with femininity norms in order to be recognized as a woman.

True or false?

TRUE.

Take a moment to reflect on this paradox below (optional).

| Women are expected to conform to a double standard, which is being athletic whilst still being feminine. Traditional feminine ideals revolve around submission, quietness, domestication and subdue behavior, all of which supresses the energy, passion and toughness required to play sports. Therefore, society forces women to still take on a sexualized, submissive and delicate role in sports by preventing participation in true contact sports, forcing them to dress in sexualized outfits and making preference to women partaking in “showcase” sports (i.e. figure skating or dance) rather than aggressive sports (i.e. football). These gendered norms infiltrate society to the point where we don’t notice their impact on women participating in sports, however, many elite athletes face these stigmatizations and role expectations every day. |

B) Masculinity, Disability, and Murderball

Exercise 9: Notebook/Padlet Prompt

Watch the film, Murderball and respond to the question in the padlet below (you will have an opportunity to return to the film at the end of this module).

The authors of “Cripping Sport and Physical Activity: An Intersectional Approach to Gender and Disability” observe that the “gendered performance of the wheelchair rugby players can…be interpreted as a form of resistance to marginalized masculinity” (332) but also point out that it may reinforce “ableist norms of masculinity.” After viewing the film, which argument do you agree with?

a) Murderball celebrates a kind of resistance to marginalized masculinity

| Murderball reinforces ableist norms of masculinity in a convoluted, indirect manner.

Strength, endurance, toughness and athleticism are seen as fundamental pillars to traditional norms of masculinity. Though a film like Murderball is expected to disband these ideals, it subtly reinforces gender ideology in numerous ways. For example, the hypermasculinity, as described by Lindemann and Cherney (2008), is frequently portrayed in Murderball as a means to overcompensate the characters’ physical impairments, which reinforces the idea that such impairments act to reduce masculinity. Not only are these ideals reinstated during sports play, but the film forces these characters to behave hyper-masculine in their lives outside of the court such as through dominance-seeking behaviors. Additionally, the male-centered narrative of the film further portrays the loss of physical ability to only be a masculine issue, being that the loss of dominance and power is more detrimental to men. To truly disband these ideologies, it would have been beneficial for the film to also follow the lives of disabled female athletes, to contrast the experiences and drive home the sense of independence, power and benefit derived from sports participation. |

Section Three: Taking a Shot

A) Resistance

B) Calling out Supercrip

Exercise 10: Mini Assignment (worth 5% in addition to the module grade)

1) Do you agree with the critique of the “supercrip” narrative in this video? Why or why not? Find an example of the “supercrip” Paralympian in the 2024 Paris Paralympics or Special Olympics coverage and explain how it works.

| The “superclip narrative” depicts paralympic sports’ experience as a platform for overcoming their disabilities, rather than emphasizing the sport or athlete as a standalone phenomenon. It tends to overemphasize the experience of impairment rather than the true athleticism and dedication involved in sports performance. I believe the video “We’re the Superhumans” reinforces superchip narratives because the focus is on the disability of athletes being transformed or overcome through participation in sports, while it lacks acknowledgement of both the struggles and the diverse ranges of disability. Additionally, the narratives provided in this video add a guilt-factor to disabled individuals, as though by not being an elite paralympic athlete, they are “giving in” to their impairments and letting it dictate their life when they should be instead “defying the odds” and “proving everybody wrong”. In the 2024 Paris Paralympics, it was found that over half (59%) of viewers watched to see these athletes defy odds regarding their abilities, while only 37% of surveyed respondents watched to see genuine fearsome competition (Singhal, 2024). This statistic reinforced the superclip narrative by reinforcing the Paralympics as a platform for inspiration rather than being worthy of genuine competition and interest. This almost creates a pity factor stigmatization, driving home the fact that viewers see the Paralympics as a catalyst for inspiration derived from personal bias.

Link to article: https://medium.com/design-bootcamp/redefining-excellence-the-campaign-to-shift-perceptions-of-paralympians-487d6c6132e8 |

2) Does the film Murderball play into the supercrip narrative in your opinion? How does gender inform supercrip (read this blog for some ideas)?

| Murderball certainly plays into the superclip narrative. By reinforcing the “inspiration porn” (Stella Young, as cited in Mattlin, 2022) that forcefully guides able-bodied individuals to follow or show interest in paralympic sports , Murderball too creates uncharacteristically high standards for impaired individuals to reach in order to gain any sort of acceptance, acknowledgement and broadcasting. This puts undue pressure on non-athlete disabled people, who may enjoy a more subdue existence, and silencing those who are not out to prove anything extravagant to feel worthy. Gender-based narratives in Murderball also inform superclip by, again, forcing the belief that disability is a predominantly a male issue, or is felt more significantly by men, because loss of typical physical abilities affect men more. The lack of female presence and portrayal of disabled female experience in the documentary heighten this gender-based superclip by suggesting that athleticism is a way to overcome a loss of dominance for males only, and that retaining this control through participation in sports is more characteristically male behavior. It almost seems to suggest that disabled femineity is more acceptable than male impairment because females don’t have a strong enough desire to prove their ability to overcome hurdles through athleticism. Thus, disabled females are supposed to act more submissive or victimized as the result of their impairment, while men are expected to train tremendously to prove control over their impairments. |