1.10 Liriodendron tulipifera

Julia Hallam

Liriodendron tulipifera

Liriodendron tulipifera

Author: Julia Hallam

1. Plant Description

Liriodendron tulipifera is also known as Tulip Tree, Tulip Poplar, or Yellow Poplar because of its tulip-like flowers in the spring (Smith, n.d.). It is commonly mistaken for a poplar species, as the leaves have long stems (petioles) that make the leaves dance and flutter like poplar species are known for (Lauritzen, 2023). The tulip tree, however, is a member of the magnolia family and is a deciduous angiosperm (Smith, n.d.). It is a facilitative upland plant that is most often found in non-wetland locations (Lauritzen, 2023). Tulip trees have tall and mostly straight trunks with little to no branching on the lower half of the tree, often 15 m or more above the ground (Lauritzen, 2023). The tulip tree is a perennial tree native to eastern North America and can grow upwards of 30-50 meters tall (University of Guelph Arboretum, n.d.).

2. Identification

Liriodendron tulipifera is found in the Carolinian zone in Ontario along the South shore of Lake Huron, the North shore of Lake Erie, and in the Niagara Peninsula (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, 2014). Tulip trees are also native to the Eastern United States (Beck, 1990).

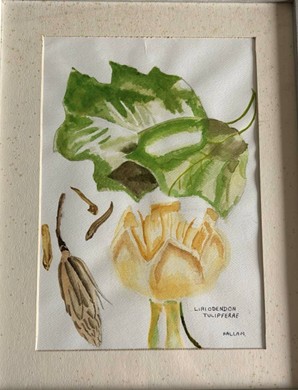

Tulip trees are tall, fast-growing trees that can reach approximately 25-35 meters in height, and their trunks can reach 50-160 cm in diameter (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, 2014). Their leaves are large and flat, with four pointed lobes and a light green colour, approximately 7-12 cm in length (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, 2014). Liriodendron tulipifera leaves have alternate growth and have long petioles (Lauritzen, 2023). These leaves are shown below in Figures 2 and 7.

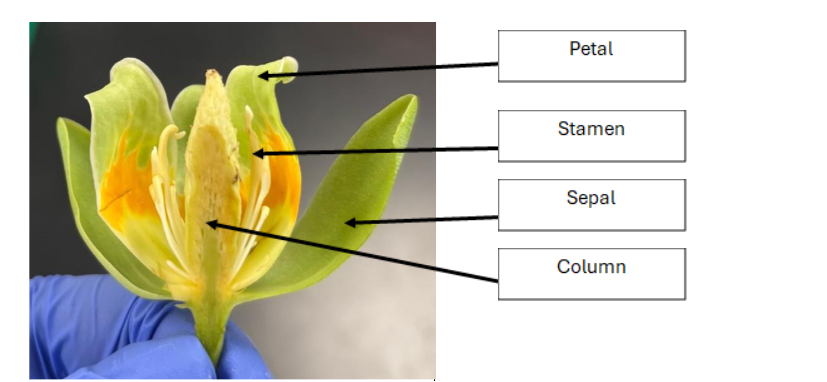

Tulip trees flower in mid to late spring with singular tulip-shaped flowers that have six petals. The petals are light green in colour with a band of bright orange in the middle and a pale-yellow base. These trees flower for the first time between the ages of 15 and 20 and will continue to flower for upwards of 200 years in the right conditions (Beck, 1990). These flowers are shown below in figures 1.10.2 A & B.

3. Cultivation Information

Tulip trees need full sun and deep, rich, and moist soil as they have roots that spread widely and grow deeply to accommodate their fast growth (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, 2014). Partial shading may be required if the tree is planted in a dry area to prevent drought stress (Lauritzen, 2023). Because of this, they require a lot of moisture in the summer and grow best in sandy loam or sand (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, 2014). Tulip trees are most often grown from seed or propagated from softwood cuttings and stump sprouts (Lauritzen, 2023). Seeds require cold stratification for 60-90 days in order to germinate (Lauritzen, 2023). This can be done at home by planting them in moist sand or peat in a container that is refrigerated for 70-90 days at 0-10 °C.

4. Indigenous Knowledge/Cultural history

Since Tulip trees grow fast and relatively straight, their wood is often used for woodworking for making furniture, plywood, siding, and construction lumber (Merkle et al., 1993). Traditionally, the bark of the Tulip tree was used by First Nation people of North America as a tonic, a fever-reducing medicine, and to treat malaria (Quassinti et al., 2019). This tree is mostly used as an ornamental tree now; however, its large foliage and flowers are desired by landscapers (Quassinti et al., 2019). The medicinal properties of the essential oils created using plant matter from the Tulip tree have been studied and linked with the potential for Tulip tree derivatives as anticancer drugs; however, further research is still being completed (Quassinti et al., 2019).

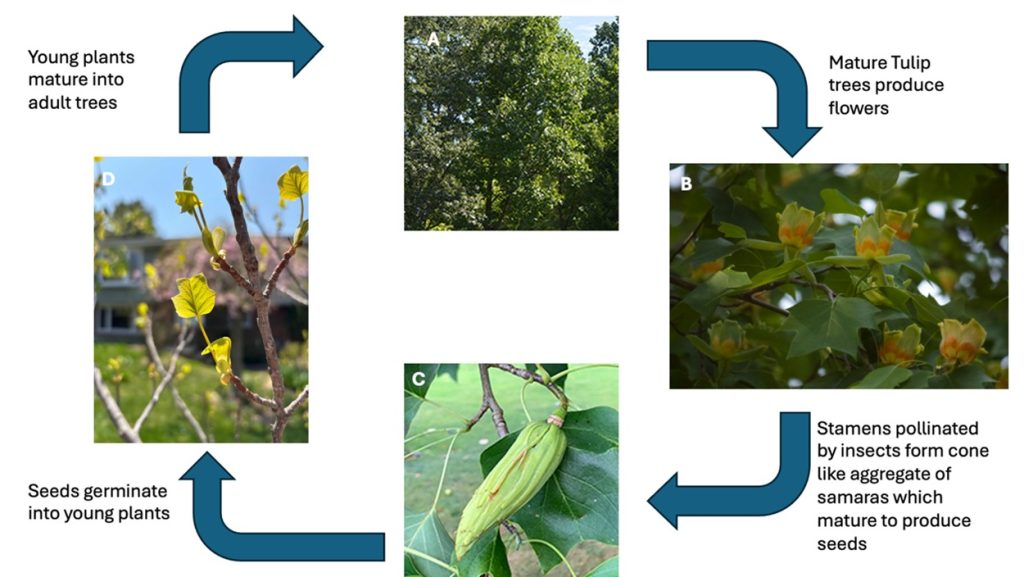

5. Life Cycle

Tulip Tree seeds must overwinter in natural or simulated conditions to overcome their natural dormancy and germinate (Beck, 1990). The seeds also require adequate moisture and a suitable seedbed of mineral soils or well-decomposed organic matter (Beck, 1990). Once overwintered, the seeds germinate and grow into young plants that have a deep taproot (Beck, 1990).

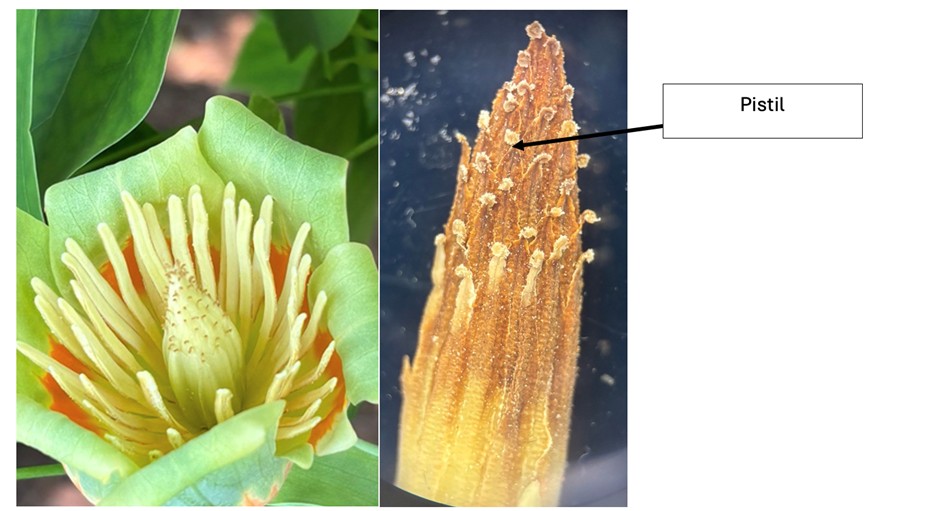

They flower for the first time after 15-20 years of growth, between April and June, and are pollinated while the stamens are still light coloured by insects or their own pollen (Beck, 1990). The flowers have many stamens in a single flower (20-50), and a single yellow style and a central stigma, which will develop into a brown cone-like aggregate of samaras, each samara a single seed with one wing of papery tissue that aids in dispersal (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2014). This is shown in Figure 4 below. Pollen from insects is brought to the stigmas by pollinators such as flies, bees, and beetles, mostly, with birds such as hummingbirds occasionally acting as pollinators (Beck, 1990). Tulip trees flower for 2-6 weeks, depending on weather and maturity; however, the column of each flower is only open to receive pollen for 12-24 daylight hours (Beck, 1990). Their flowers produce nectar on the orange strip of colour to attract pollinators, as shown in Figure 7 below, and on the tips of the petals (Liu et al, 2019). The seeds ripen and mature in the fall and drop from the tree to be dispersed by wind during fall and winter (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2014). Tulip trees produce a lot of seeds each year; however, they only have a viability of ~5-20% (Beck, 1990).

6. Anatomy and Physiology

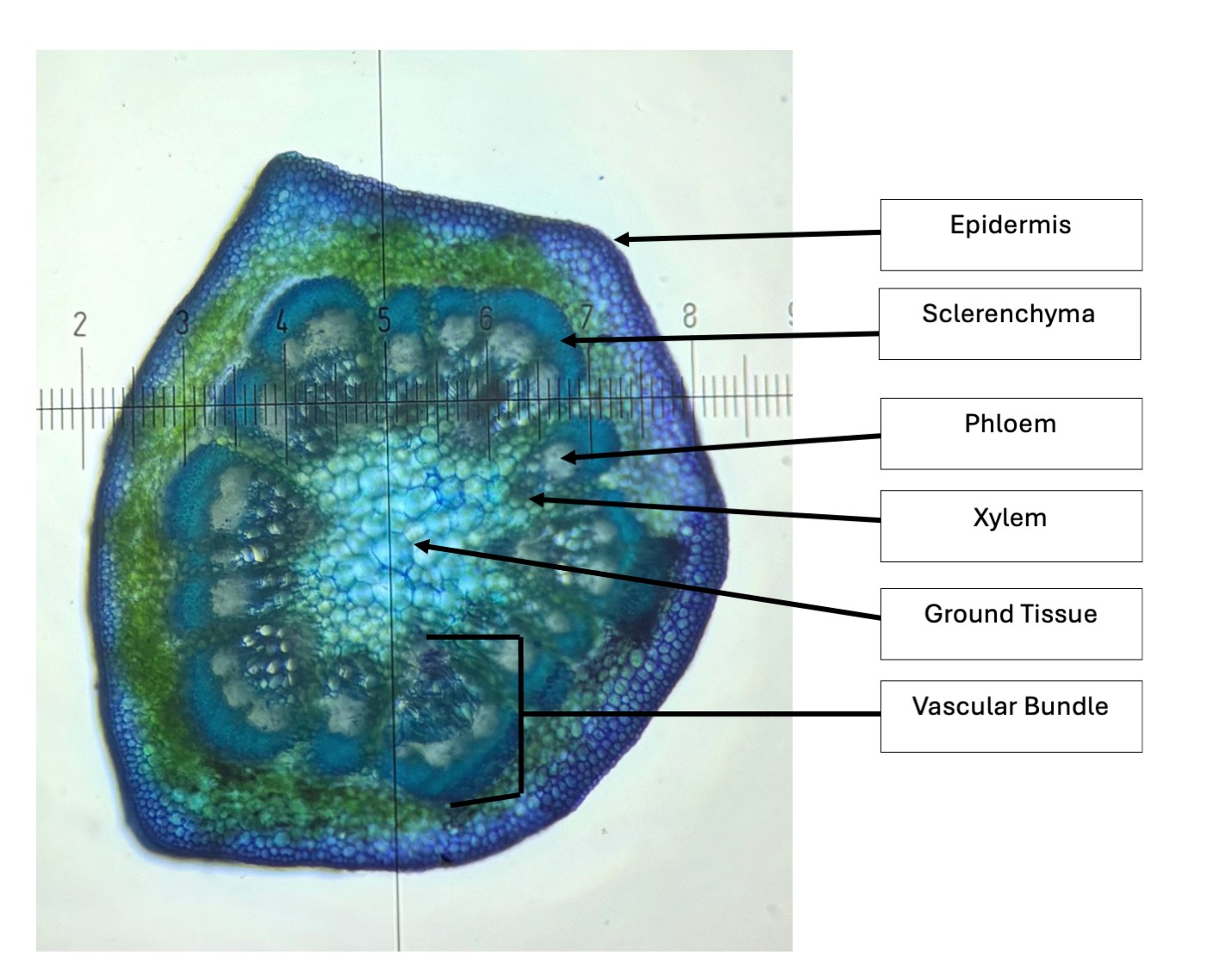

A study on the Liriodendron tulipifera species found that in arid climates, some Tulip trees had sun leaves and shade leaves of different compositions (Akinshina et al., 2020). These sun leaves contained around 20-30% more chlorophyll than the shade leaves, and the sun leaves were smaller, had a thicker cuticle to prevent water loss, and the cells in the parenchyma were larger on average (Akinshina et al., 2020). These adaptations prevented overheating of the leaves while also preventing water loss. The sun leaves were found to have larger and more numerous stomata and vascular bundles to aid in transpiration when water was plentiful (Akinshina et al., 2020). Figure 9 below shows the cross-section of a petiole containing these tissues for a better understanding.

Tulip trees have a relatively high stress resistance to biotic and abiotic stressors; however, they do still respond to mechanical stress by producing tension wood (Jin & Kwon, 2009). Tension wood is formed in response to the stem of a woody plant being bent or disturbed from its natural upright position (Jin & Kwon, 2009). It modifies the secondary wall structure in angiosperms to reduce the size and frequency, and is often characterized by a gelatinous layer in the fibres (Jin & Kwon, 2009). The study found that two-year-old Tulip tree plants showed tension wood formation after both 7 and 14 days of mechanical bending; however, the gelatinous layer usually present in angiosperm fibres was absent despite the reduced production of lignin in the xylem cells (Jin & Kwon, 2009).

7. Summary

Tulip trees are fast-growing, deciduous trees that make a beautiful addition to any yard or park in the Carolinian zone.

References

Akinshina, N. G., Duschanova, G. M., & Toderich, K. N. (2020). Xeromorphic features of the leaves of Liriodendron tulipifera L. (Magnoliaceae) in the arid climate of Central Asia. Moscow University Biological Sciences Bulletin, 75(4), 212–217. https://doi.org/10.3103/S0096392520040021

Beck, D. E. (1990). Liriodendron tulipifera L. In R. M. Burns & B. H. Honkala (Tech. coords.), Silvics of North America: Vol. 2. Hardwoods (Agriculture Handbook 654, pp. 406–416). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_2/liriodendron/tulipifera.htm

Jin, H., & Kwon, M. (2009). Mechanical bending-induced tension wood formation with reduced lignin biosynthesis in Liriodendron tulipifera. Journal of Wood Science, 55(5), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10086-009-1053-1

Lauritzen, J. E. (2023). Plant guide for tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Rose Lake Plant Materials Center. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/plantmaterials/mipmcpg14104.pdf

Liu, H., Ma, J., & Li, H. (2019). Transcriptomic and microstructural analyses in Liriodendron tulipifera Linn. reveal candidate genes involved in nectary development and nectar secretion. BMC Plant Biology, 19, Article 531. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-2140-0

Merkle, S. A., Wilde, H. D., & Sommer, H. E. (1993). In vitro culture of Liriodendron tulipifera. In M. R. Ahuja (Ed.), Micropropagation of woody plants (pp. 303–320). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-8116-5_17

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. (2014). Tulip tree. Government of Ontario. https://www.ontario.ca/page/tulip-tree

Oregon State University. (n.d.). Liriodendron tulipifera. OSU Landscape Plants. https://landscapeplants.oregonstate.edu/plants/liriodendron-tulipifera

Quassinti, L., Maggi, F., Ortolani, F., Lupidi, G., Petrelli, D., Vitali, L. A., Miano, A., & Bramucci, M. (2019). Exploring new applications of tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera L.): Leaf essential oil as apoptotic agent for human glioblastoma. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26, 30485–30497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-06217-4

Smith, A. (2021, October 28). Inside the collections – HOCU 6162. U.S. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/inside-the-collections-hocu-6262.htm

University of Guelph Arboretum. (n.d.). Tulip tree – Liriodendron tulipifera. https://arboretum.uoguelph.ca/thingstosee/trees/tuliptree