1.6 Fragaria Virginiana

Alexa Drouillard

Fragaria Virginiana

Author: Alexa Drouillard

1. Plant Description

Fragaria virginiana is also known as the wild strawberry. It belongs to the Rosaceae family. The plant is perennial and herbaceous (Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, n.d.). It is native but not unique to the Carolinian zone; it’s found in southern Canada (including the Carolinian zone) and throughout the USA.

2. Identification

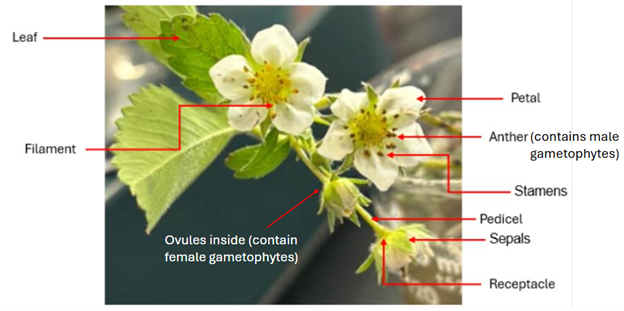

This plant has a few distinguishing characteristics that make it identifiable. It hugs the ground, growing between 5 and 10 cm tall (Ontario Wildflowers, n.d.). It has hairy leaf petioles about 15 cm long and a hairy flower stalk. Each petiole has one trifoliate leaf, and every flower has five white petals (Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, n.d).

The wood strawberry, Fragaria vesca, is similar in appearance but can be differentiated in a few ways. The sepals of F. vesca are turned away from the fruit, while in F. virginiana they turn inward (Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, n.d.). F. virginiana flowers grow at the same height as the leaves, while F. vesca flowers sit above the leaves (Ontario Wildflowers, n.d.).

3. Cultivation

F. virginiana is available to home gardeners and is not difficult to grow at home. The plant can often be purchased at nurseries specializing in native plants. F. virginiana should be planted in the spring or fall to avoid frost. They need 4-6 hours of sunlight per day and should be planted about 30cm apart. Sandy soil is the best option for the wild strawberries, and they only need to be watered at extremely hot temperatures (Gillette, 2024).

4. Cultural Use

Wild strawberries have been used for a long time by indigenous peoples in North America. The fruit was a part of their diet, and the leaves were sometimes used to make tea. It was also a common strategy to plant wild strawberries to attract wildlife. Wild strawberries also had medicinal uses, such as being used to treat burns (Kim et al., 2012). They were also used to treat heart and stomach ailments (University of Alberta Library, n.d.).

5. Life Cycle

Development: The plant begins to form buds in autumn, and the flower bud becomes visible around mid-April. The plant begins to flower in late May, and the fruit ripens from late June to July (University of Alberta Library, n.d.).

Embryogenesis: F. virginiana is octoploid, meaning eight sets of chromosomes (2n = 56) (University of Alberta Library, n.d.).

Germination: F. virginiana has about a 70% germination rate after 30 days, based on data collected from both fresh and year-old seeds from northeastern Alberta (University of Alberta Library, n.d.). Germination occurs at 21°C (Garry Oak Ecosystems Recovery Team, 2025).

Seed Development: The seeds are round, tear-shaped, and about 1mm long (University of Alberta Library, n.d.). What we commonly perceive as the “seeds” of a strawberry are actually the plant’s ovaries, which each contain a single seed inside (Deng & Marshall, n.d.).

Leaf Arrangement: Each petiole contains one set of trifoliate leaves. The leaves are green, oval-shaped, with toothed edges. On average, leaves are about 7cm long and 4cm wide (Deng & Marshall, n.d.). There is one leaf per node along the stem (Fragaria virginiana – common strawberry).

Reproduction: The main way F. virginiana reproduces is by runners, which are stems that grow along the soil surface and produce new roots and plants from the buds (Deng & Marshall, n.d.). Seeds are dispersed by birds and mammals, while wild strawberries are pollinated by bees, flies, and ants (University of Alberta Library, n.d.).

Evolution: F. virginiana was hybridized with Fragaria chiloensis, a type of strawberry from Chile, about 250 years ago in France to create the commercial strawberry that is sold worldwide (Gündüz, n.d.).

6. Anatomy & Physiology

Tissues: A unique tissue in F. virginiana is the receptacle, which is the tissue underneath the sepals that turns into the fleshy red tissue of the berry. Strawberries differ from many plants because the “fruit” that is eaten is actually swollen receptacle tissue, and not fruit derived from a single ovary (Shahan et al, 2019).

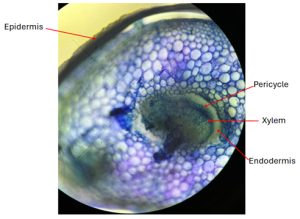

Transport: A study revealed that CO₂ concentrations for optimum photosynthesis in strawberries are about 600 ppm. Concentrations of 750 ppm were found to be too high, leading to nutrient deficiency (Keutgen et al.,1997).

Phytohormones / Defences: The Strawberry Mottle Virus (SMoV) is the most common virus in F. virginiana, and all Fragaria species are susceptible. Infected plants can sometimes be symptomless, making detection difficult. Symptoms include mottle, ringspot, yellowing, leaf distortion, and reduced fruit yield/size (Moyer, C. et al). Strawberries defend themselves with receptors that detect pathogens and trigger responses such as cell wall reinforcement and production of reactive oxygen species (Amil-Ruiz et al., 2011).

References

Amil-Ruiz, F., Blanco-Portales, R., Muñoz-Blanco, J., & Caballero, J. L. (2011, November). The strawberry plant defense mechanism: A molecular review. Plant and Cell Physiology, 52(11), 1873-1903. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcr136

Deng, W., & Marshall, C. (n.d.). Fragaria virginiana (Wild Strawberry), Rosaceae. Lake Forest College. https://www.lakeforest.edu/academics/majors-and-minors/environmental-studies/fragaria_virginiana_%28wild-strawberry%29-rosaceae

Kim, G., Szorad, E., Chen, E., Linney, D., & Laakmann, A. (2012, November). The wild strawberry: A sacred purifier. The Good Food World. https://www.goodfoodworld.com/2012/11/the-wild-strawberry-a-sacred-purifier/

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. (n.d.). Fragaria virginiana. https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=frvi

Garry Oak Ecosystems Recovery Team. (2025, September 16). Fragaria virginiana. Garry Oak Ecosystems Recovery Team. https://goert.ca/species/fragaria-virginiana

Gillette, B. (2024, August 7). How to grow and care for wild strawberry (fragaria virginiana). The Spruce. https://www.thespruce.com/wild-strawberry-care-guide-7229743

Gündüz, K. (n.d.). Fragaria virginiana [Overview]. ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/fragaria-virginiana

Keutgen, N., Chen, K., & Lenz, F. (1997). Responses of strawberry leaf photosynthesis, chlorophyll fluorescence and macronutrient contents to elevated CO₂. Journal of Plant Physiology, 150(4), 395–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0176-1617(97)80088-0

Ontario Wildflowers. (n.d.). Wild Strawberry Fragaria virginiana. Ontario Wildflowers. https://ontariowildflowers.com/main/species.php?id=679

Shahan, R., Li, D., & Liu, Z. (2019). Identification of genes preferentially expressed in wild strawberry receptacle fruit and demonstration of their promoter activities. Horticulture Research, 6(50). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-019-0134-6

University of Alberta. (n.d.). ERA: Education and Research Archive. University of Alberta. https://era.library.ualberta.ca