2 Constructing gender bias through EFL textbooks: An analysis of representations in the Chinese context. Are our textbooks teaching gender stereotypes?

Xin Pang

Xin’s video reflection about the Capstone Project

Uncovering gender messages in EFL materials

Textbooks not only shape language instruction but also serve as instruments of ideological transmission (Çağlak, 2025). But what if the materials we rely on every day are silently reinforcing outdated gender roles (Clark, 2016; Song & Xiong, 2022)?

This post draws on my Capstone Project, which investigates how gender is represented in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) textbooks used in Chinese primary schools. It focuses on both textual and visual aspects, including the frequency of character visibility, role assignments and related activities. In addition, it also considers how these representations align with broader educational expectations in China and briefly describes the role of teachers in mediating the content of textbooks.

This project aims to extend existing research by analyzing how gender is constructed in EFL textbooks commonly used by Chinese primary school students. The study is guided by the research question – How is gender represented in commonly used EFL textbooks for young learners in China? – and one sub-question – What patterns and proportions of gender representation (in both texts and visuals) are found in these textbooks?

Textbooks are more than just about language learning

In the Chinese context, EFL textbooks go beyond simply teaching language. They carry an additional responsibility of shaping students’ values, behaviours, and perceptions of the world. This makes them powerful tools for transmitting not only linguistic knowledge but also broader social and cultural messages, including ideas about gender.

Several key points illustrate why this matters:

- EFL Textbooks in China are approved by the government and follow national curriculum standards (Huang & Liu, 2024).

- Both teachers and students view textbooks as the definitive authority for learning, relying on them to define correct knowledge and acceptable behavior (Lee, 2014, 2018).

- What textbooks show helps shape gender beliefs by presenting models of behaviour, values, and social norms (Foroutan, 2012; Wiraningsih et al., 2025).

- Younger learners are still developing their social identities and may not have enough critical skills to question information in everyday learning materials.

Understanding these points helps explain why examining gender representation in textbooks is essential. The next section outlines the textbook chosen for this study and the analytical framework used to explore how gender is represented.

Textbook Selection and Analysis Framework

This study focuses on the New Standard English (Grade 5, Book 2) textbook, published by the Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press (FLTRP) in 2013 (hereafter referred to as NSE). Designed in line with the national curriculum and widely adopted in Chinese primary schools, the NSE integrates diverse activities, promotes self-directed learning, and follows task-based teaching methodologies (Yuan, 2018). Given its influence and alignment with the 2022 English curriculum standards (Luan, 2022), it offers a meaningful context for examining gender representation.

Unit 1 (13 pages) was chosen because it presents varied roles and daily scenarios suitable for analyzing gender visibility and role assignment. The unit is generally addressed at the start of the second semester, a formative stage for Grade 5 students (aged 10 – 11) when they begin using English in more structured and communicative ways (NSE, 2013).

Inspired by Song and Xiong (2022) and Zhang et al. (2022), this study uses a qualitative content analysis approach (Krippendorff, 2019) to examine both textual and visual elements. Three dimensions guide the analysis:

- Character visibility: frequency of male and female appearances;

- Role assignment: occupations, family roles, or social positions;

- Activity types: domains such as physical, academic, family-oriented, or social tasks.

This study adopts an accessible, descriptive approach to compare male and female representations across text and image, aiming to determine whether they are portrayed equally and, if not, to identify emerging patterns.

What I found

Even in such a short unit, several clear patterns have stood out.

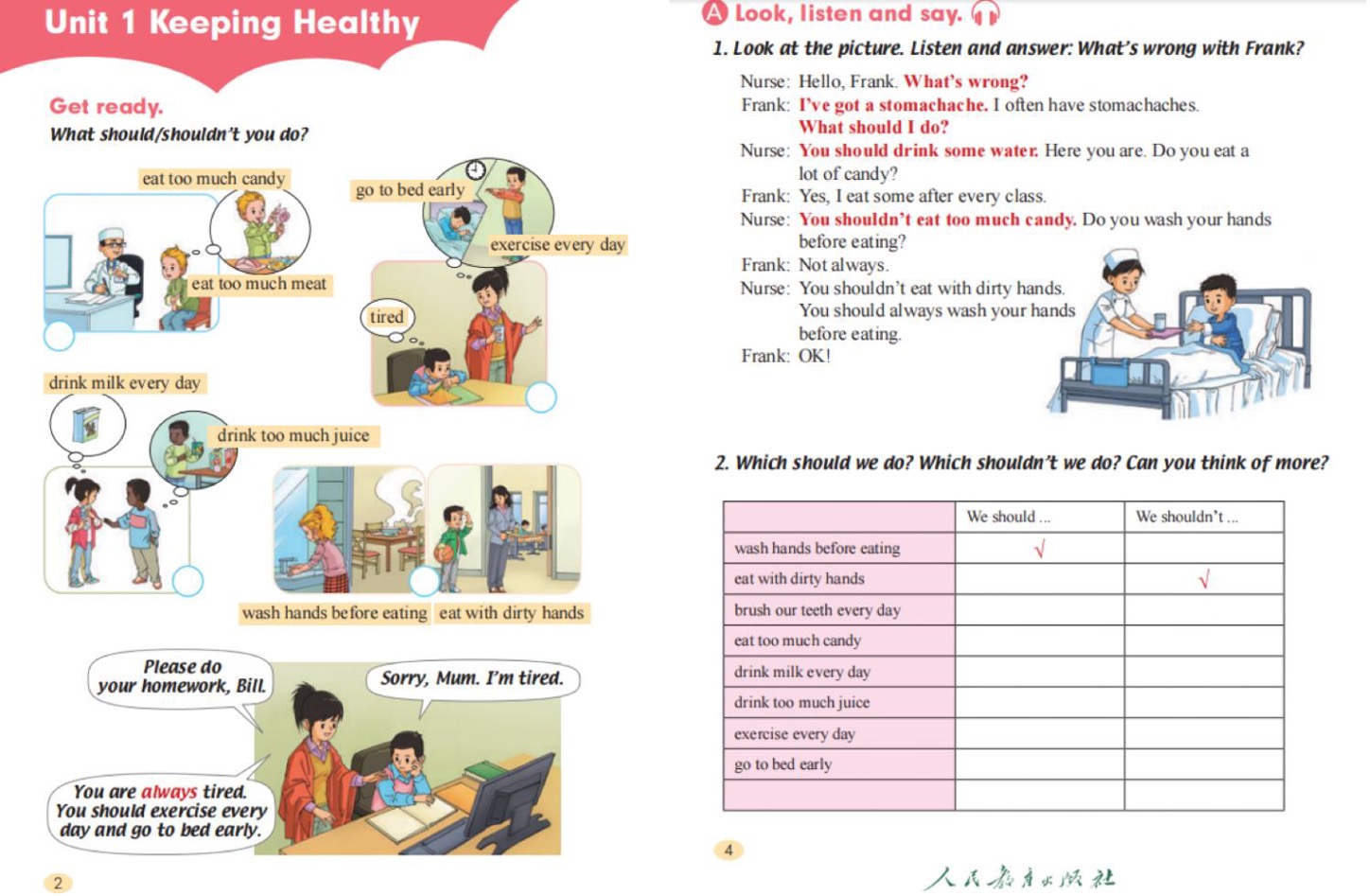

- Male dominance in active roles

As can be seen in Figure 1, men are shown as doctors and in roles typically associated with expertise and public authority. In contrast, women are mostly depicted as mothers, teachers, or nurses – the roles that support or guide others, rather than lead.

As shown in Figure 2, a hungry boy wants to eat immediately, but his mother reminds him to wash his hands, again casting the female as a moral guide. Such scenes may lead young learners to see adult men as authority figures, boys as casual or mischievous, and women as caring enforcers of social norms, shaping early ideas of gender roles in both private and public life.

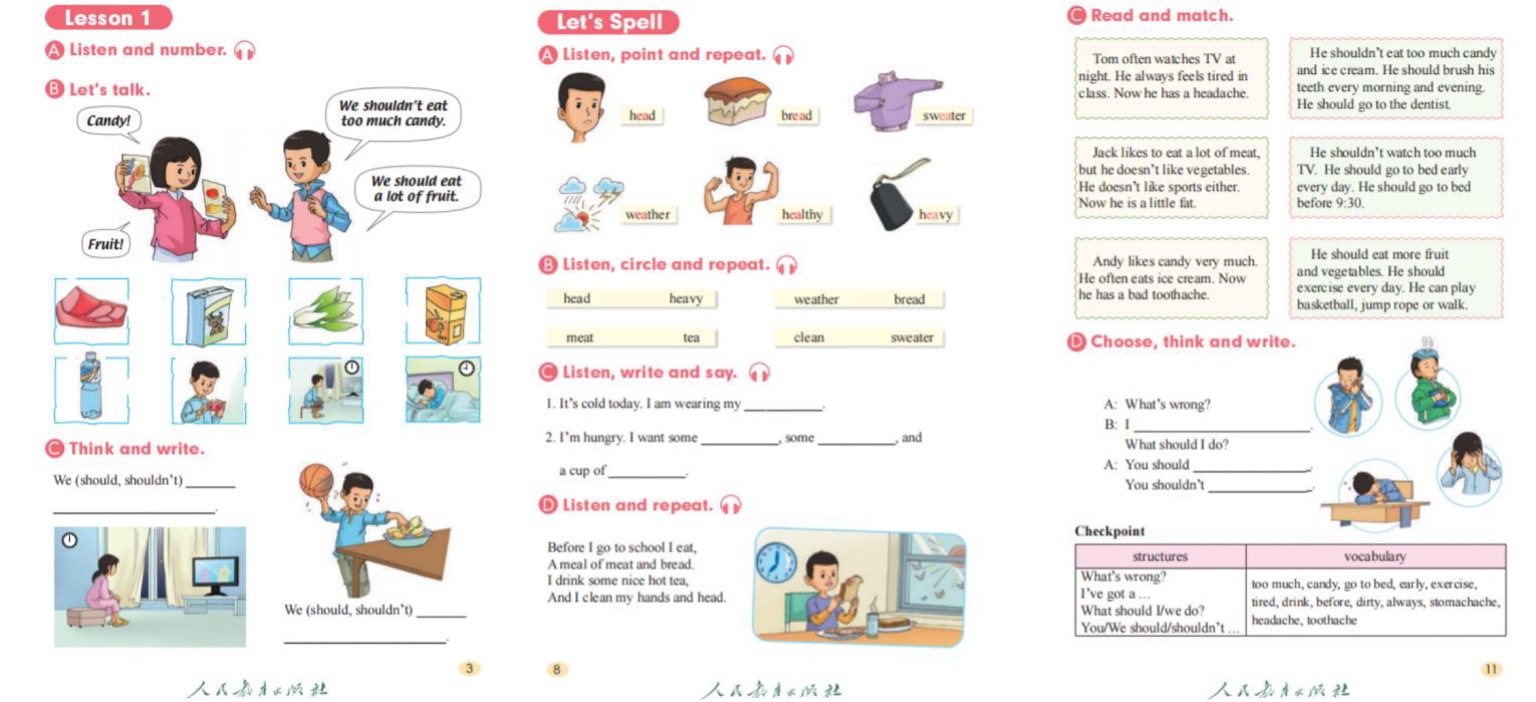

- Boys as the language models

Considering reading and grammar exercises, male characters are used more often as the “default” examples whereas female characters are either secondary or absent altogether.

As shown in Figure 3, the “Let’s read” section features two letters – one is from a boy to a girl, and the other is from a girl to a boy. However, the follow-up comprehension chart includes only the sentence structures that begin with “He”, centering on the male character as the linguistic model.

Similarly, as can be seen in Figure 4, across practice activities on pages 3, 8, and 11, the images accompanying neutral or non-gendered tasks (where gender should not be relevant) almost exclusively depict male characters. On page 11 in particular, all example sentences use male names such as Tom, Jack, and Andy as subjects. This visual and textual consistency subtly positions boys as normative participants in tasks, reinforcing the notion that boys are the default primary actors or speakers in various situations, while the presence of the opposite gender is implicitly sidelined or rendered invisible.

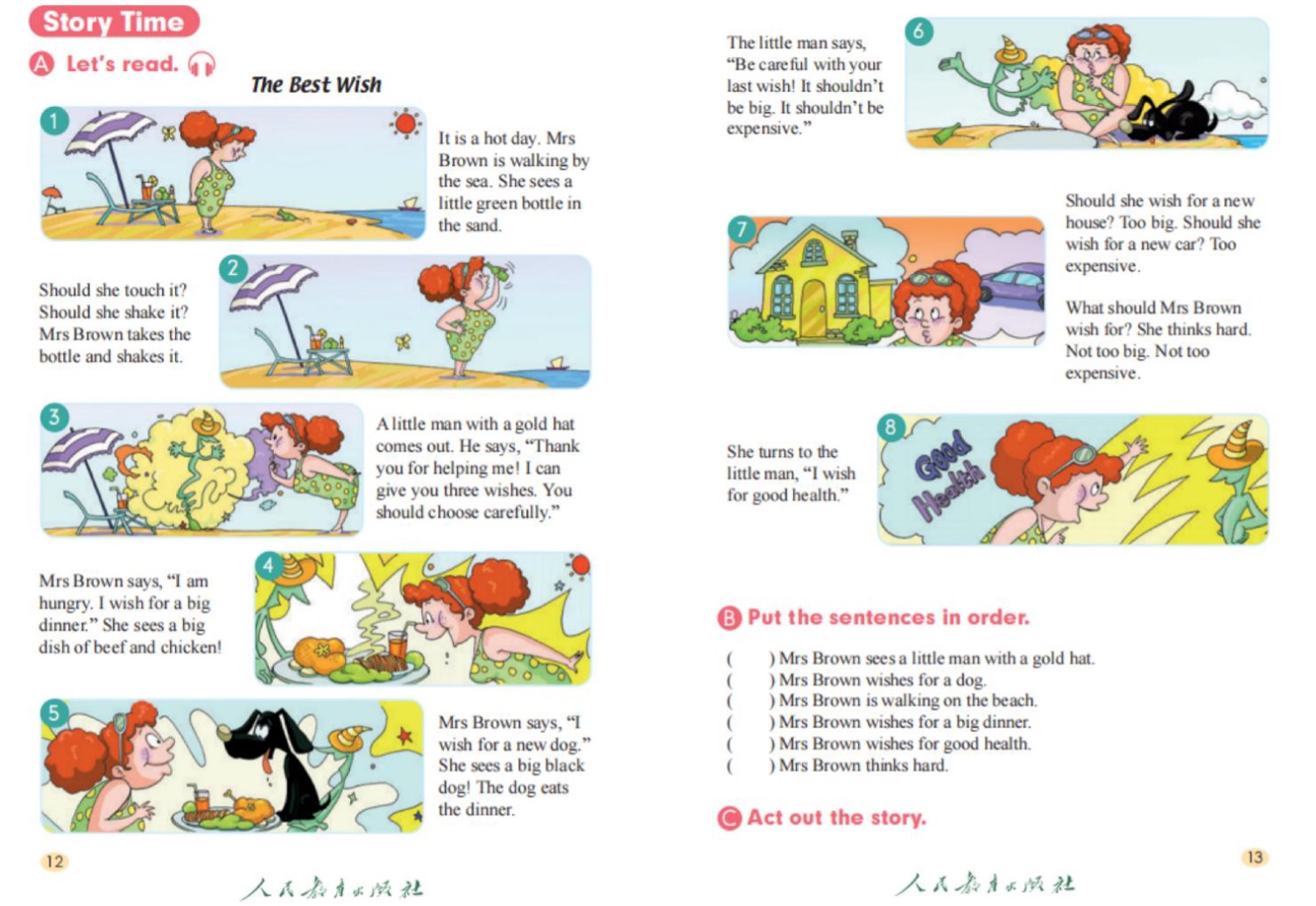

- Limited female agency

Girls rarely appear alone or as main actors in storylines. As can be seen in Figure 5, the only female-led story, in “Story Time,” features Mrs. Brown, identified only by her marital status, reinforcing how women are framed relationally rather than independently. This highlights the consistent underrepresentation of female agency in both text and image.

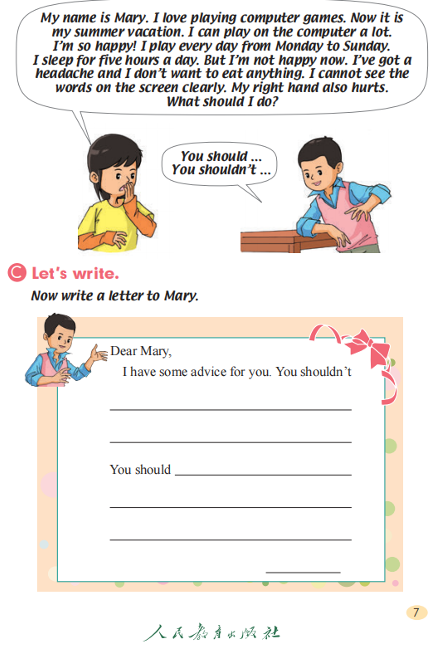

There was, however, a small exception to this. As shown in Figure 6, a girl says she enjoys video games, which challenges the exiting stereotype of girls generally not engaging in such past time activities. Still, this moment is isolated and not reinforced elsewhere in the unit.

While none of these representations seem offensive on their own, the repetition of these patterns sends strong, silent messages (Widodo, 2018). For example, men are active, central, and professional, while women are supportive, moral, and quiet.

Shaping beliefs through textbooks

The findings discussed above highlight that textbooks do far more than present language content. In China, government-approved English textbooks teach not only language but also moral guidance and humanistic values, reflecting a broader ideological role (Ministry of Education, 2011, cited in Zhang et al., 2022). When children are repeatedly exposed to patterns in which boys take action while girls support or observe, they may begin to see these divisions as “normal” or “expected.” Over time, such messages can shape how students, especially girls, view their own potential both inside and outside the classroom.

Given this influence, textbooks are critical to how the curriculum is implemented, but their actual impact depends greatly on how teachers interpret and use them (Fan et al., 2025). If teachers actively notice and challenge stereotypes, they can help students build more balanced perspectives. Conversely, if these biases are not challenged, they may become firmly rooted in students’ minds.

Conclusion

This study examined gender representation in the New Standard English (Grade 5, Book 2) textbook used in China’s EFL classrooms, focusing on character visibility, role assignments, and activities.

The analysis showed a consistent male-dominant pattern: men appeared more often, took varied and active roles, and were default subjects in language tasks, while women were mainly caregivers, moral guides, or passive observers with few independent roles. Such persistent biases can subtly shape students’ views of social roles during key stages of identity development.

Future research could examine more textbooks, different grade levels, and include classroom observations to see how teachers address these messages; long-term studies could address how repeated exposure influences gender perceptions.

In the meantime, teachers might want to consider and/or reflect on the following key questions when it comes gender representation in the materials they use:

- To what extent are the materials they use influence learners’ perceptions of gender?

- Are their classroom practices unconsciously reinforcing the gender biases in the materials, or are they actively challenging them?

- How can students be naturally guided to keep thinking critically about the examples in the activities in their language learning?

After all, real-life examples and activities are an integral part of language learning. By reflecting on these questions, language teachers will be able to move towards a more forward-thinking and critical pedagogy that promotes gender equality in the classroom and helps students to develop a more balanced and respectful view of their social roles.

References

Çağlak, I. (2025). Gender Representation and Sexism in International Language Coursebooks for Tertiary Education. Journal of Language Teaching and Learning, 15(1), 20-45. Retrieved from https://www.jltl.com.tr/index.php/jltl/article/view/727

Clark, I. (2016). A Qualitative Analytic Case Study of Subliminal Gender Bias in Japanese ELTs. SAGE Open, 6(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016653437

Fan, L., Wijayanti, D., Meng, D., Li, K., & Mailizar, M. (2025). The role of textbooks in the implementation of curriculum development: a comparative study through the lens of Chinese and Indonesian teachers’ views. ZDM. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-025-01692-1

Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. (2013). English (Grade 5, Book 2) – Starting from Grade 1. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Foroutan, Y. (2012). Gender representation in school textbooks in Iran: The place of languages. Current Sociology, 60(6), 771–787. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392112459744

Huang, P., & Liu, X. (2024). Challenging gender stereotypes: representations of gender through social interactions in English learning textbooks. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), Article 819. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03293-x

Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071878781

Lee, J. F. K. (2014). Gender representation in Hong Kong primary school ELT textbooks – a comparative study. Gender and Education, 26(4), 356–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2014.916400

Lee, J. F. K. (2018). Gender representation in Japanese EFL textbooks — A corpus study. Gender and Education, 30(3), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2016.1214690

Luan, Y. (2022). Exploration of moral education strategies in primary school English based on unit-integrated instruction: A case study of Module 7, Grade 6, Waiyan Edition (Grade 1 Start) [In Chinese]. Research on Primary and Secondary School Teaching, 23(5), 25–30. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-5728.2022.05.005

Song, Z., & Xiong, T. (2022). A comparative study of the visual representation of gender in two series of secondary English as a foreign language textbooks in China. In T. Xiong, D. Feng, & G. Hu (Eds.), Cultural knowledge and values in English language teaching materials (pp. 95–115). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1935-0_5

Widodo, H. P. (2018). A critical micro-semiotic analysis of values depicted in the Indonesian Ministry of National Education-endorsed secondary school English textbook. In H. P. Widodo, M. R. Perfecto, L. V. Canh, & A. Buripakdi (Eds.), Situating moral and cultural values in ELT materials: The Southeast Asian context (Vol. 9, pp. 131–152). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63677-1_8

Wiraningsih, P., Suwastini, N. K. A., & Padmadewi, N. N. (2025). Gendered pictorial in Indonesian EFL textbook “When English rings the bells”. International Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn), 19(2), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.11591/edulearn.v19i2.21474

Yuan, W. (2018). A comparative study of PEP and FLTRP English textbooks in Chinese primary schools: Based on teachers as users [Master’s thesis, Qinghai Normal University]. CNKI. https://doi.org/10.7666/d.D01594797

Zhang, L., Zhang, Y., & Cao, R. (2022). “Can we stop cleaning the house and make some food, Mum?”: A critical investigation of gender representation in China’s English textbooks. Linguistics and Education, 69(Complete). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2022.101058

Media Attributions

- Figure 1 – NSE, 2013, pp. 2 and 4

- Figure 2 – NSE, 2013, p. 10

- Figure 3 – NSE, 2013, p. 6

- Figure 4 – NSE, 2013, pp. 3, 8, and 11

- Figure 5 – NSE, 2013, pp. 12-13

- Figure 6 – NSE, 2013, p. 7