Chapter 7: Global Business

Chapter 7 Learning Outcomes

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain why nations and companies participate in international trade and how they measure that trade.

- Describe the concepts of absolute and comparative advantage.

- Describe how companies can enter foreign markets through importing and exporting.

- Explain why a business might opt for outsourcing and contract manufacturing in foreign countries.

- Explain how companies enter the international market through licensing agreements or franchises.

- Explain how strategic alliances and joint ventures differ in structure, commitment, and goals.

- Explain why a company might make a direct investment in operations conducted in another country.

- Describe how companies reduce costs through contract manufacturing and outsourcing.

- Explain how cultural, economic, legal, and political differences between countries create challenges to successful business dealings.

- Discuss the various initiatives designed to reduce international trade barriers and promote free trade.

The Globalization of Business

Globalization is the process of increasing economic and social integration between countries, and the increased flow of goods, services, and people across borders.

Do you wear Nike shoes or Timberland boots? Listen to Beyoncé, Pitbull, Twenty One Pilots, or The Neighborhood on Spotify? If you answered yes to either of these questions, you’re a global business customer. Both Nike and Timberland manufacture most of their products overseas. Spotify is a Swedish enterprise.

Take an imaginary walk down Orchard Road, the most fashionable shopping area in Singapore. You’ll pass department stores such as Tokyo-based Takashimaya and London’s very British Marks & Spencer, both filled with such well-known international labels as Ralph Lauren, Polo, Burberry, and Chanel. If you need a break, you can also stop for a latte at Seattle-based Starbucks.

When you’re in the Chinese capital of Beijing, don’t miss Tiananmen Square. Parked in front of the Great Hall of the People, the seat of the Chinese government, are fleets of black Buicks, cars made by General Motors in Flint, Michigan. If you’re adventurous enough to find yourself in Faisalabad, a medium-sized city in Pakistan, you’ll see Hamdard University, located in a refurbished hotel. Step inside its computer labs, and the sensation of being in a faraway place will likely disappear when you recognize the familiar Microsoft flag on the computer screen—the same one emblazoned on screens in Microsoft’s hometown of Seattle and just about everywhere else on the planet.

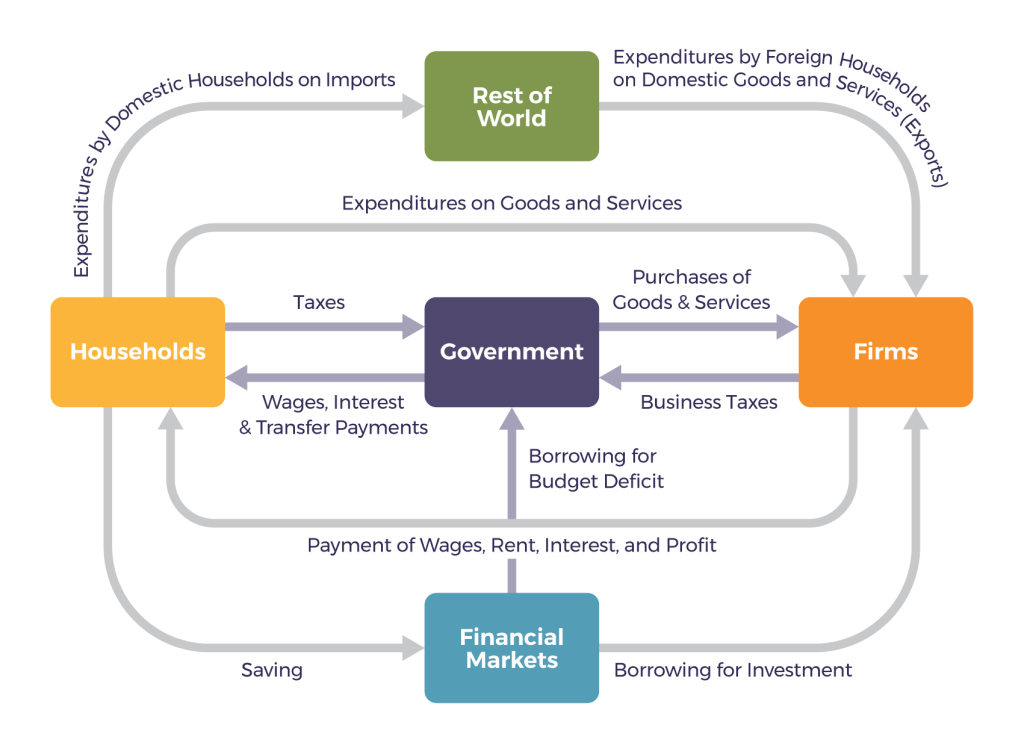

The globalization of business is bound to affect you. Not only will you buy products manufactured overseas, but it’s likely that you’ll meet and work with individuals from various countries and cultures as customers, suppliers, colleagues, employees, or employers. The bottom line is that the globalization of world commerce has an impact on all of us ~ as evidenced in Figure 7.1 below, The Expanded Circular Flow Model. Therefore, it makes sense to learn more about how globalization works.

Never has business spanned the globe the way it does today, and will continue to do in the future. But why is international business important? Why do companies and nations engage in international trade? What strategies do they employ in the global marketplace? How do governments and international agencies promote and regulate international trade? These questions and others will be addressed in this chapter. Let’s start by looking at the more specific reasons why companies and nations engage in international trade.

Why Do Nations Trade?

Nations trade to capitalize on their unique advantages and to foster economic growth, enhance living standards, and build relationships with other countries. Trade allows countries to access products and services they cannot produce efficiently or lack altogether, enhancing consumer choice and quality of life. Tropical fruits are imported by colder countries like Canada because they cannot be grown domestically. By producing for export, businesses can achieve economies of scale, lowering production costs and making goods more affordable domestically and abroad. Automotive manufacturers in Germany produce vehicles on a large scale, selling them globally. Trade fosters innovation and the spread of new technologies, ideas, and practices, driving development and competitive advantage. Collaboration in international technology markets has accelerated advancements in renewable energy. Trade builds interdependence, reducing the likelihood of conflicts and fostering diplomatic relations. For example, the European Union promotes trade among its member states to strengthen regional stability and cooperation. Exporting goods and services generates income, creating jobs and boosting the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The export of oil and gas has been a significant contributor to Canada’s economic growth.

Why does Canada import automobiles, steel, digital phones, and apparel from other countries? Why don’t we just make them ourselves? Why do other countries buy wheat, chemicals, machinery, and lumber products from us? Because no national economy produces all the goods and services that its people need. Countries are importers when they buy goods and services from other countries; when they sell products to other nations, they’re exporters. In 2023, the total value of world trade in merchandise and commercial services was $30.5 trillion, a 2% decrease from the previous year. This was due to a 5% decline in the value of goods trade, while the value of services trade increased by 9%. The World Trade Organization (WTO) projects that the volume of world merchandise trade will grow by 0.8% in 2023 and 3.3% in 2024.[1]

Factors that have impacted trade in recent years include:[2]

- The war in Ukraine

- High inflation

- Tightening monetary policy in major economies

- High energy prices

- Rising interest rates

- Geopolitical tensions

- Food and energy insecurity

- Increased risk of financial instability

- High levels of external debt

Absolute and Comparative Advantage

To understand why certain countries import or export specific products, you need to realize that every country (or region) cannot produce the same products. The cost of labour, the availability of natural resources, and the level of know-how vary greatly around the world. Most economists use the concepts of absolute advantage and comparative advantage to explain why countries import some products and export others.

Absolute Advantage

A nation has an absolute advantage if, (1) it’s the only source of a particular product, or (2) it can make more of a product using fewer resources than other countries. Because of climate and soil conditions, for example, France had an absolute advantage in wine making until its dominance of worldwide wine production was challenged by the growing wine industries in Italy, Spain, the United States, and, more recently, Canada. Unless an absolute advantage is based on some limited natural resource, it seldom lasts. That’s why there are few, if any, examples of absolute advantage in the world today.

Comparative Advantage

When a country decides to specialize in a particular product, it must sacrifice the production of another product (opportunity costs). Countries benefit from specialization—focusing on what they do best, and trading the output to other countries for what those countries do best. Canada’s top export destinations are the United States, China, and the United Kingdom. In 2023, the United States was the destination for 76% of Canada’s exports.[3]

Canada’s energy exports make up 22% of its total exports. In 2023, the top exports in this category were mineral fuels, oils, and distillation products. Cars and parts are one of Canada’s biggest exports, making up 19% of its total exports. In 2023, the top exports in this category were vehicles other than railway and tramway. Consumer goods make up 12% of Canada’s total exports. Canada exports a variety of minerals, including potash, metallurgical coal, and diamonds. In 2022, Canada was the world’s biggest exporter of potash. Canada also exports machinery, nuclear reactors, boilers, pearls, precious stones, metals, and coins.[4]

The United States, for instance, is increasingly an exporter of knowledge-based products, such as software, movies, music, and professional services (management consulting, financial services, and so forth). America’s colleges and universities, therefore, are a source of comparative advantage, and students from all over the world come to the United States for the world’s best higher-education system. France and Italy are centers for fashion and luxury goods and are leading exporters of wine, perfume, and designer clothing. Japan’s engineering expertise has given it an edge in such fields as automobiles and consumer electronics. And with large numbers of highly skilled graduates in technology, India has become the world’s leader in low-cost, computer-software engineering.

How can we predict, for any given country, which products will be made and sold at home, which will be imported, and which will be exported? This question can be answered by looking at the concept of comparative advantage, which exists when a country can produce a product at a lower opportunity cost compared to another nation. But what’s an opportunity cost?

Opportunity costs

Since resources are limited, every time you make a choice about how to use them, you are also choosing to forego other options. Economists use the term opportunity cost to indicate what must be given up to obtain something that is desired. A fundamental principle of economics is that every choice has an opportunity cost.

- If you sleep through your economics class (not recommended, by the way), the opportunity cost is the learning you miss.

- If you spend your income on video games, you cannot spend it on movies.

- If you choose to marry one person, you give up the opportunity to marry anyone else.

In short, opportunity cost is all around us. The idea behind opportunity cost is that the cost of one item is the lost opportunity to do or consume something else; in short, opportunity cost is the value of the next best alternative. Since people and businesses must choose, they inevitably face trade-offs in which they must give up things they desire to get other things they desire more.

Opportunity Cost and Individual Decisions

In some cases, recognizing the opportunity cost can alter personal behaviour. Imagine, for example, that you spend $10 on lunch every day at work. You may know perfectly well that bringing lunch from home would cost only $3 a day, so the opportunity cost of buying lunch at the restaurant is $7 each day (that is, the $10 that buying lunch costs minus the $3 your lunch from home would cost). Ten dollars each day does not seem to be that much. However, if you project what that adds up to in a year—250 workdays a year × $10 per day equals $2 500—it is the cost, perhaps, of a decent vacation. If the opportunity cost were described as “a nice vacation” instead of “$10 a day,” you might make different choices.

Opportunity Cost and Societal Decisions

Opportunity cost also comes into play with societal decisions. Universal health care in the U.S. would be nice, but the opportunity cost of such a decision would be less housing, environmental protection, or national defense. These trade-offs also arise with government policies. For example, after the terrorist plane hijackings on September 11, 2001, many proposals, such as the following, were made to improve air travel safety:

- The federal government could provide armed “sky marshals” who would travel inconspicuously with the rest of the passengers. The cost of having a sky marshal on every flight would be roughly $3 billion per year.

- Retrofitting all U.S. planes with reinforced cockpit doors to make it harder for terrorists to take over the plane would have a price tag of $450 million.

- Buying more sophisticated security equipment for airports, like three-dimensional baggage scanners and cameras linked to face-recognition software, would cost another $2 billion.

Lost time can be a significant component of opportunity cost.

However, the single biggest cost of greater airline security does not involve money. It is the opportunity cost of additional waiting time at the airport. According to the United States Department of Transportation, more than 800 million passengers took plane trips in the United States in 2012. Since the 9/11 hijackings, security screening has become more intensive, and consequently, the procedure takes longer than in the past. Say that, on average, each air passenger spends an extra 30 minutes in the airport per trip. Economists commonly place a value on time to convert an opportunity cost in time into a monetary figure. Because many air travelers are relatively highly paid business people, conservative estimates set the average “price of time” for air travelers at $20 per hour. Accordingly, the opportunity cost of delays in airports could be as much as 800 million (passengers) × 0.5 hours × $20/hour, or $8 billion per year. The opportunity costs of waiting time can be just as substantial as costs involving direct spending.

Measuring Trade Between Nations

To evaluate the nature and consequences of its international trade, a nation looks at two key indicators: the balance of trade and balance of payments.

Balance of Trade

A country’s balance of trade is calculated by subtracting the value of its imports from the value of its exports. If a country sells more products than it buys, it has a favourable balance, called a trade surplus. If it buys more than it sells, it has an unfavourable balance, or a trade deficit.

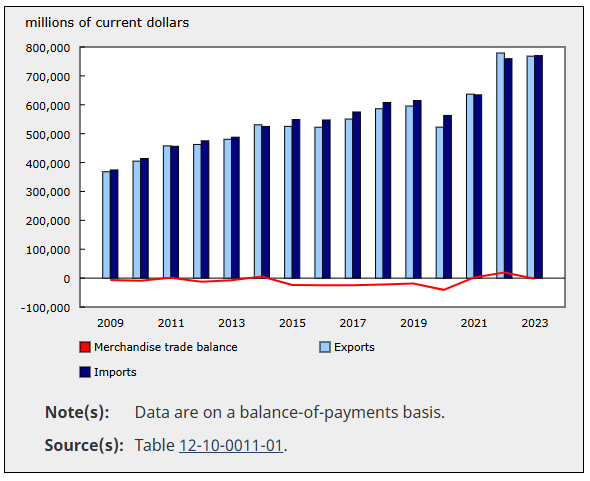

In 2023, the value of Canada’s annual merchandise exports decreased 1.4% to $768.2 billion, while the value of annual imports rose 1.4% to $770.2 billion.[5] Between 1980 and 2008, Canada recorded a positive trade balance every year, except 1991 and 1992. From 2009 onwards, the trade balance shifted to a deficit. In 2021, it switched again to a trade surplus, with energy products making the largest share of exports (Refer to Figure 7.2). The United States remains the country’s biggest trading partner.[6] Other countries, such as China and Taiwan, which manufacture high volumes for export, have large trade surpluses because they sell far more goods overseas than they buy.

Deficits

A nation's deficit is when a government spends more money than it receives in revenue over a period of time. This can be due to a number of factors, including excessive spending or borrowing. A nation’s deficit can be an indicator of its financial health and economic situation.

Are trade deficits a bad thing? Not necessarily. They can be positive if a country’s economy is strong enough both to keep growing and to generate the jobs and incomes that permit its citizens to buy the best the world has to offer. That was certainly the case in Canada in the 1990s and early 2000s. Some experts, however, are alarmed by trade deficits. Investment guru Warren Buffett, for example, cautions that no country can continuously sustain large and burgeoning trade deficits. Why not? Because creditor nations will eventually stop taking IOUs from debtor nations, and when that happens, the national spending spree will have to cease. “A nation’s credit card,” he warns, “charges truly breathtaking amounts. But that card’s credit line is not limitless”.[7]

Surpluses

A country has a trade surplus when it sells more to other countries than it buys from them. It’s the opposite of a trade deficit. A surplus can lead to economic growth and employment, but it can also cause higher prices, interest rates, and a more expensive currency.

Trade surpluses aren’t necessarily good for a nation’s consumers. For example, Japan’s export-fueled economy produced high economic growth in the 1970s and 1980s but most domestically made consumer goods were priced at artificially high levels inside Japan itself, so high that many Japanese traveled overseas to buy the electronics and other high-quality goods on which Japanese trade was dependent.

CD players and televisions were significantly cheaper in Honolulu or Los Angeles than in Tokyo. How did this situation come about? Though Japan manufactures a variety of goods, many of them are made for export. To secure shares in international markets, Japan prices its exported goods competitively. Inside Japan, because competition is limited, producers can put artificially high prices on Japanese-made goods. Due to several factors (high demand for a limited supply of imported goods, high shipping and distribution costs, and other costs incurred by importers in a nation that tends to protect its own industries), imported goods are also expensive.[8]

Today, Japan may not be as expensive as you think. While prices for certain goods and services are generally higher than you’d find in countries like China, Thailand, and Vietnam, on the whole, you might discover that costs are lower than in places such as Singapore, Australia, and Scandinavia.[9]

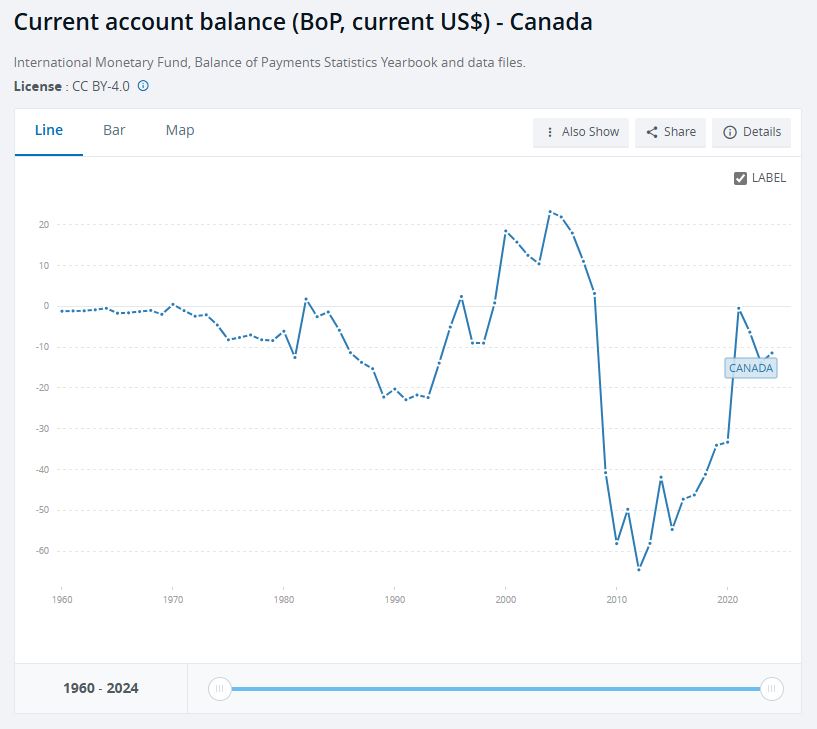

Balance of Payments

The second key measure of the effectiveness of international trade is balance of payments: the difference, over a period of time, between the total flow of money coming into a country and the total flow of money going out. As in its balance of trade, the biggest factor in a country’s balance of payments is the money that flows as a result of imports and exports. But the balance of payments includes other cash inflows and outflows, such as cash received from or paid for foreign investment, loans, tourism, military expenditures, and foreign aid. For example, if a Canadian company buys some real estate in a foreign country, that investment counts in the Canadian balance of payments, but not in its balance of trade, which measures only import and export transactions. In the long run, having an unfavorable balance of payments can negatively affect the stability of a country’s currency. Canada has experienced unfavorable balances of payments since the turn of the century, which has forced the government to cover its debt by borrowing from other countries.

The balance of payments records an economy’s transactions with the rest of the world. Balance of payments accounts are divided into two groups: the current account, which records transactions in goods, services, primary income, and secondary income, and the capital and financial account, which records capital transfers, acquisition or disposal of nonproduced, nonfinancial assets, and transactions in financial assets and liabilities. [10]

Refer to Figure 7.3, Statistics Canada chart to review Canada’s current account balance throughout the years 1960-2024. In Canada, a positive current account balance indicates that the country is exporting more than it imports, while a negative current account balance means the opposite. The Statistics Canada website provides the most current statistics for various key measures. For example, below are a few of the 2024 balance of payments statistics.

For the year 2024, the current account balance posted a $15.6 billion deficit, a narrowing of $2.8 billion compared with 2023. The reduction of the deficit was largely due to the investment income surplus increasing from $0.7 billion in 2023 to $8.4 billion in 2024, as higher profits earned by Canadian investors abroad outpaced payments.[11]

The trade in goods deficit widened from $0.6 billion in 2023 to $6.9 billion in 2024. Total imports of goods rose 1.9% to reach $785.4 billion in 2024 on widespread increases led by consumer goods (+$7.6 billion), moderated by lower imports of energy products (-$5.5 billion).[12]

Total exports of goods increased 1.1% to reach $778.6 billion in 2024. Higher exports of metal products (+$10.4 billion), mainly gold, and consumer goods (+$5.4 billion) were partially offset by lower exports of motor vehicles and parts (-$7.3 billion). Within the energy products category, exports of crude oil (+$8.3 billion) increased significantly in 2024, following the completion of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project in May, but were partially offset by lower exports of natural gas (-$5.0 billion).[13]

Below are a few interesting facts about who owes money to whom:

- Canada’s national debt is the combined debt of all three levels of government: federal, provincial, and territorial. The federal debt (the difference between total liabilities and total assets) stood at $1,236.2 billion as of March 31, 2024. The federal debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratio was 42.1 per cent, up from 41.1 per cent in the previous year. The government remains committed to its fiscal anchor of reducing the federal debt as a share of the economy over the medium term.[14]

- As of 2021, China owed Canada $371 million in loans it incurred decades ago, and is not expected to repay them in full until 2045.[15]

- As of 2024, Pakistan owed China $26.6 billion for money borrowed for infrastructure and energy projects.[16]

- The United States boasts both the world’s biggest national debt in terms of dollar amount and its largest economy, which translates to a debt-to-GDP ratio of approximately 121.31%. The United States’ government’s spending exceeds its income most years, and the US has not had a budget surplus since 2001.[17]

- Japan, China, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and Luxembourg own the most U.S. debt, in that order.[18]

Opportunities in International Business

The fact that nations exchange billions of dollars in goods and services each year demonstrates that international trade makes good economic sense. For a company wishing to expand beyond national borders, there are a variety of ways it can get involved in international business. Let’s take a closer look at the more popular ones.

Importing and Exporting

Importing (buying products overseas and reselling them in one’s own country) and exporting (selling domestic products to foreign customers) are the oldest and most prevalent forms of international trade. For many companies, importing is the primary link to the global market. American food and beverage wholesalers, for instance, import for resale in U.S. supermarkets the bottled waters Evian and Fiji from their sources in the French Alps and the Fiji Islands, respectively.[19] Other companies get into the global arena by identifying an international market for their products and becoming exporters. The Chinese, for instance, are fond of fast foods cooked in soybean oil. They also have an increasing appetite for meat, therefore, they need high-protein soybeans to raise livestock. The United States exported $15.06 billion worth of soybeans to China in 2023, making it the top destination for US soybean exports.[20]

A few reasons why companies may engage in importing include:

- Importing to reduce costs as importing may be more affordable than producing the same product locally.

- Importing new products before competitors in an attempt to become a leader in the industry.

- Importing the products that are not core to the business will allow a business to specialize. For example, companies can specialize in a part of a good, such as producing just brake pads for cars, and rely on other companies or countries for the rest.

- Importing increases competition for domestic products. Companies may import products from other countries to compete with other businesses selling domestic products.

A few reasons why companies may engage in exporting include:

- Exporting can help a company reach new markets or expand in existing markets and increase sales and profits.

- Exporting can spread business risk by diversifying into multiple markets instead of one domestic market.

- Exporting can improve a company’s competitiveness against both domestic and international competitors.

- Exporting can lead to enhanced innovation and the acquisition of new skills.

- Exporting can help boost a company’s profile and credibility.

- Exporting may allow a company to take advantage of trade agreements with reduced trade barriers.

- Exporting can help a company manage seasonal product use and market fluctuations.

- Exporting may allow a company to take advantage of exchange rates, depending on which currency is at a higher rate.

When goods are shipped from one country to another, they must go through customs. Customs is the process of declaring and paying taxes on imported goods. All countries have different regulations for what can and cannot be imported. Some items, such as drugs or weapons, are prohibited because they are dangerous. Other items, such as used tires or chemicals, are restricted because they may harm the environment. The purpose of customs is to protect a country’s economy, environment, jobs, and residents.

Licensing and Franchising

A company that wants to get into an international market quickly while taking only limited financial and legal risks might consider licensing agreements with foreign companies. An international licensing agreement allows a foreign company (the licensee) to sell the products of a producer (the licensor) or to use its intellectual property (such as patents, trademarks, copyrights) in exchange for what is known as royalty fees. Here’s how it works: You own a company in Canada that sells coffee-flavored popcorn. You’re sure that your product would be a big hit in Japan, but you don’t have the resources to set up a factory or sales office in that country. You can’t make the popcorn here and ship it to Japan because it would get stale. So, you enter a licensing agreement with a Japanese company that allows your licensee to manufacture coffee-flavored popcorn using your special process and to sell it in Japan under your brand name. In exchange, the Japanese licensee would pay you a royalty fee – perhaps a percentage of each sale or a fixed amount per unit.

The best way to understand licensing is to think about something that a company owns that they agree to sell to another company to use, either locally or globally. For example, Lego, a company that produces building block toys, had to get a license from companies like Disney when they wanted to create their Star Wars Lego sets.

Another popular way to expand overseas is to sell franchises. Under an international franchise agreement, a company (the franchiser) grants a foreign company (the franchisee) the right to use its brand name and to sell its products or services. The franchisee is responsible for all operations but agrees to operate according to a business model established by the franchiser. In turn, the franchiser usually provides advertising, training, and new-product assistance. Franchising is a natural form of global expansion for companies that operate domestically according to a franchise model, including restaurant chains, such as McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken, and hotel chains, such as Holiday Inn and Best Western. Unlike franchising in the franchisor’s home country, where the franchisor grants the franchisee a license to use the marketing, branding and operations of the franchisor, international franchising usually involves selling the franchise rights to a third party to operate as the master franchisee in that area, giving them the rights to open company-owned outlets and sub-franchise in the country or region.[21]

Contract Manufacturing and Outsourcing

Canadian companies are increasingly drawing on a vast supply of relatively inexpensive skilled labour to perform various business services, such as software development, accounting, and claims processing. This is known as outsourcing. In contrast, contract manufacturing is a specific type of outsourcing related specifically to products when two parties sign a contract manufacturing agreement.

Because of high domestic labour costs, many U.S. and Canadian companies manufacture their products in countries where labour costs are lower. This arrangement is called international contract manufacturing, a form of outsourcing. A domestic company might contract with a local company in a foreign country to manufacture one of its products. It will, however, retain control of product design and development and put its own label on the finished product. Contract manufacturing is quite common in the U.S. apparel business, with most American brands being made in a number of Asian countries, including China, Vietnam, Indonesia, and India.[22]

Thanks to twenty-first-century information technology, non-manufacturing functions can also be outsourced to nations with lower labour costs. Canadian companies are increasingly drawing on a vast supply of relatively inexpensive skilled labour to perform various business services, such as software development, accounting, and claims processing. With a large, well-educated population with English language skills, India has become a centre for software development and customer call centres. In the case of India, as you can see in the graph below, the attraction is not only a large pool of knowledge workers but also significantly lower wages.[23]

Strategic Alliances and Joint Ventures

A strategic alliance is an agreement between two companies (or a company and a nation) to pool resources in order to achieve business goals that benefit both partners. A strategic alliance and a joint venture are both collaborative business arrangements between companies, but they differ in structure, commitment, and goals.

Strategic Alliance

What if a company wants to do business in a foreign country but lacks the expertise or resources? Or what if the target nation’s government doesn’t allow foreign companies to operate within its borders unless it has a local partner? In these cases, a firm might enter a strategic alliance with a local company or even with the government itself.

A strategic alliance is an agreement between two companies (or a company and a nation) to pool resources to achieve business goals that benefit both partners. Alliances range in scope from informal cooperative agreements to joint ventures— alliances in which the partners fund a separate entity (perhaps a partnership or a corporation) to manage their joint operation.

An alliance can serve a number of purposes:

- Enhancing marketing efforts

- Building sales and market share

- Improving products

- Reducing production and distribution costs

- Sharing technology

- Sharing risks

With a strategic alliance, companies remain legally independent and the focus is on sharing resources, knowledge, and access to markets. The agreement is typically less binding and easier to dissolve compared to a joint venture. An example of a strategic alliance is Starbucks and PepsiCo partnering to market and distribute Starbucks-branded ready-to-drink beverages globally. Strategic alliances are used to enter new markets, share technological expertise, or achieve cost efficiencies without significant financial or operational commitment.

A few examples of a strategic equity alliance (one company buys equity in the other, or both buy equity in each other) are:

- One prominent example of a successful strategic partnership is the partnership between Apple and Nike. This collaboration brought together Apple’s technological expertise and Nike’s extensive knowledge in sports and fitness. Through this partnership, they created the Nike+ iPod, a product that revolutionized the way people track their workouts using their iPod and Nike shoes.[24]

- Tesla and Panasonic formed a strategic alliance to build Tesla’s Gigafactory, a large-scale battery manufacturing plant in the United States. This collaboration focuses on producing lithium-ion batteries to support Tesla’s electric vehicles (EVs) and energy storage products. Under the agreement, Tesla manages the land, buildings, and utilities for the Gigafactory, while Panasonic manufactures and supplies cylindrical lithium-ion cells. Panasonic also invests in equipment and machinery for production. By co-locating suppliers and optimizing manufacturing processes, this partnership aims to reduce battery costs through economies of scale. The Gigafactory’s output supports Tesla’s goal of producing mass-market EVs, such as the Model 3, and lowering energy storage costs across applications. The alliance highlights the strategic benefit of combining Tesla’s EV expertise with Panasonic’s battery technology to advance sustainable energy solutions and the EV market.[25]

- A non-equity strategic alliance is when two companies share resources and proprietary information. An example of this is between Kroger and Starbucks; any time you shop at the grocery chain, there’s a Starbucks stand near the door.[26]

Joint Venture

A joint venture involves two or more companies forming a new, independent legal entity to pursue a specific business objective or project. The companies share ownership, profits, risks, and governance in the newly created entity. This typically involves significant capital investment and a long-term commitment. The joint venture ends when the project or objective is completed unless extended by the parties. An example of a joint venture is Sony Ericsson, which was the resulting company formed by Sony and Ericsson to produce mobile phones (eventually acquired by Sony). Another prime example of a joint venture is the partnership between NASA and Google, which created the business Google Earth. Another example is SIA and TATA, which ventured into forming Vistara Airlines out of India. Joint ventures are used when there are large-scale, resource-intensive projects, entering highly regulated markets, or pooling expertise for mutual benefit. Refer to Table 7.1 for a comparison of the key differences between strategic alliances and joint ventures.

| Aspect | Strategic Alliance | Joint Venture |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Structure | No new entity formed | New independent entity created |

| Commitment | Flexible and less binding | Long-term and formal commitment |

| Risk and Control | Risks and control are individual | Shared risks, profits, and governance |

| Duration | Typically short to medium term | Often long-term |

| Examples | Co-branding agreements, research collaborations | Infrastructure projects, product development partnerships |

Foreign Direct Investment and Subsidiaries

Foreign Direct Investment

Many of the approaches to global expansion that we’ve discussed so far allow companies to participate in international markets without investing in foreign plants and facilities. As markets expand, however, a firm might decide to enhance its competitive advantage by making a direct investment in operations conducted in another country. Foreign direct investment (FDI) refers to the formal establishment of business operations on foreign soil—the building of factories, sales offices, and distribution networks to serve local markets in a nation other than the company’s home country. On the other hand, offshoring occurs when facilities in a foreign country replace Canadian manufacturing facilities and are used to produce goods that will be sent back to Canada for sale.

FDI is generally the most expensive commitment that a firm can make to an overseas market, and it’s typically driven by the size and attractiveness of the target market. For example, German and Japanese automakers, such as BMW, Mercedes, Toyota, and Honda, have made serious commitments to the U.S. market: most of the cars and trucks that they build in plants in the South and Midwest are destined for sale in the United States.

Subsidiary

A common form of FDI is the foreign subsidiary: an independent company owned by a foreign firm (called the parent). This approach to going international not only gives the parent company full access to local markets but also exempts it from any laws or regulations that may hamper the activities of foreign firms. The parent company has tight control over the operations of a subsidiary, but while senior managers from the parent company often oversee operations, many managers and employees are citizens of the host country. Not surprisingly, most very large firms have foreign subsidiaries. IBM and Coca-Cola, for example, have both had success in the Japanese market through their foreign subsidiaries (IBM-Japan and Coca-Cola–Japan). FDI goes in the other direction, too, and many companies operating in the United States are subsidiaries of foreign firms. Gerber Products, for example, is a subsidiary of the Swiss company Novartis, while Stop & Shop and Giant Food Stores belong to the Dutch company Royal Ahold. Where does most FDI capital end up? The graph below provides an overview of amounts, destinations (high to low income countries), and trends.

Foreign Acquisition

Walmart Example of Both FDI And Subsidiary

The acquisition of a foreign company by a domestic company is considered a form of foreign direct investment (FDI). When a company based in one country acquires a substantial ownership stake (typically 10% or more) in a business located in another country, it qualifies as FDI. The key feature of FDI is that it involves not only capital transfer but also control or significant influence over the foreign entity’s operations.

Walmart and Flipkart formed a significant business relationship when Walmart acquired a 77% majority stake in Flipkart for $16 billion in 2018. This move marked Walmart’s entry into India’s burgeoning e-commerce market, which is among the fastest-growing in the world. However, this is not a joint venture but rather an acquisition, as Walmart gained control of Flipkart while maintaining the existing brand and operations of the Indian company.

Flipkart is a leading e-commerce platform in India, and the acquisition allowed Walmart to establish a foothold in India’s online retail market to compete against Amazon. Walmart leveraged Flipkart’s extensive logistics network, while also applying its own expertise to enhance supply chain efficiency and improve customer satisfaction. Flipkart benefited from Walmart’s resources and global reach, including its financial strength and technological capabilities, while Walmart tapped into Flipkart’s local market expertise and established customer base. Walmart had to navigate India’s restrictions on foreign direct investment in multi-brand retail. The deal was structured to comply with these laws, ensuring Flipkart’s operations could continue while adapting to regulatory requirements. This acquisition highlights how multinational corporations like Walmart strategically invest in emerging markets, often through partnerships or acquisitions, rather than joint ventures. The success of such strategies hinges on aligning operational strengths, navigating local regulations, and meeting competitive challenges.[27]

Walmart’s investment in Flipkart qualifies as foreign direct investment (FDI) because it involved Walmart acquiring a controlling 77% stake in Flipkart, an Indian company, for $16 billion. This type of investment is categorized as FDI since it entails a direct investment by a foreign company (Walmart, based in the United States) into a business operating in another country (Flipkart in India). Walmart’s majority stake gives it control over Flipkart’s operations and strategic direction, characteristic of FDI.

Following the acquisition, Flipkart operates as a subsidiary of Walmart, meaning Walmart owns the company while Flipkart continues to function under its own brand and management in the local market. The deal exemplifies Walmart’s strategic move to enter India’s growing e-commerce sector and highlights the nature of FDI as a tool to penetrate foreign markets. This arrangement combines the principles of FDI with subsidiary operations, allowing Walmart to benefit from Flipkart’s established local presence while providing Flipkart with resources and expertise to expand its market share further.[28]

These strategies have been employed successfully in global business. But success in international business involves more than finding the best way to reach international markets. Global business is a complex, risky endeavor. Over time, many large companies reach the point of becoming truly multinational.

Foreign Mergers

A strategic alliance with a foreign company is not the same as a merger. These two concepts involve different types of business relationships and commitments. A strategic alliance is a formal agreement between two or more companies to collaborate and leverage each other’s resources, expertise, or market presence without forming a new legal entity or transferring ownership. A merger involves two or more companies combining to form a single new entity, often with shared ownership, resources, and management. In a merger, ownership and control are consolidated. It involves permanent restructuring. Often, one company may dissolve into the other, or both may dissolve into a newly formed entity. A strategic alliance focuses on mutual benefit without ownership transfer, while a merger represents a deeper level of integration where the entities combine to form a single organization.

A well-known example of a domestic company merging with a foreign company is the merger between Vodafone Group, based in the UK, and Idea Cellular, an Indian telecom provider. This merger created Vodafone Idea Limited, a major player in India’s telecommunications market. The merger combined the resources and market strengths of both companies to enhance competitive positioning and operational efficiencies in a rapidly evolving market. This type of cross-border merger is complex, involving regulatory approvals, alignment of corporate strategies, and integration of operations across different legal and cultural environments. These collaborations are essential for companies looking to expand their global footprint and leverage each other’s strengths in their respective markets.

Both mergers and joint ventures facilitate collaboration, but they differ significantly in purpose, scope, and legal integration.

Refer to Table 7.2 for a comparison of the key differences between strategic alliances, joint ventures, and mergers.

| Aspect | Strategic Alliance | Joint Venture | Merger |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legal Structure | No new entity created; companies remain separate | Companies remain separate | Companies combine into a single entity |

| Ownership | Independent ownership remains intact | Shared control over the joint project, not the company | Ownership is shared in the new entity |

| Control | Each company retains control over its operations | Shared risks, profits, and governance of the project, not the company | Control is unified under the merged company |

| Commitment | Collaboration is often flexible and limited | Project-based and temporary | The commitment is permanent and comprehensive |

Multinational Corporations

A company that operates in many countries is called a multinational corporation (MNC). According to Fortune’s Global 500 2024 rankings, Walmart is the world’s largest company by revenue for the 11th year in a row, with almost $648 billion in revenue in 2024. Walmart also has the most employees of any company in the world.[29] Microsoft is one of the most profitable companies in the world, along with Apple and Alphabet. As of June 2024, Apple was the most profitable company in the world, with a net income of $100 billion. Apple was also one of the companies with the largest corporate annual earnings of all time in 2021 and 2022.

Many MNCs have made themselves more sensitive to local market conditions by decentralizing their decision-making while still maintaining a fair amount of control. Today, fewer managers are dispatched from headquarters; MNCs depend instead on local talent. Not only does a decentralized organization speed up and improve decision-making, but it also allows an MNC to project the image of a local company. IBM, for instance, has been quite successful in the Japanese market because local customers and suppliers perceive it as a Japanese company. Crucial to this perception is the fact that the vast majority of IBM’s Tokyo employees, including top leadership, are Japanese nationals.[30]

Some MNCs standardize their products globally, while others adapt their products to the local region they operate within. Standardization delivers a single unified product that sits comfortably in all markets. Standardization allows manufacturers to keep costs down using one set of manufacturing tools and the same packaging, creating a truly global product in the process. Production is more straightforward with only one set of options, as opposed to multiple versions of the same product creating considerable additional costs; conversely, waste is also kept to a minimum. Compared to alternative versions that appeal directly to local users, standardized products have a mass-market appeal, ideal for travelers who can immediately appreciate what they’re getting wherever they acquire it.[31]

Here are a few examples of product standardization in foreign markets:[32]

- Sporting manufacturers, such as Nike and Adidas, retain global standardization across global markets with strict branding, marketing, and product themes remaining the same throughout. However, the sports and teams they sponsor and supply locally in each region are culturally considered to match the brand’s values and the product’s sales potential.

- Red Bull, despite its Austrian roots, with its typically European style, remains almost untouched across its international markets. It retains the same packaging, product size, and branding throughout to stay instantly recognizable. And with its prime marketing tactic supporting every type of extreme, high-energy sports, it’s market-appropriate across the masses too.

MNCs often adopt the approach encapsulated in the motto “Think globally, act locally”. They often adjust their operations, products, marketing, and distribution to mesh with the environments of the countries in which they operate. Because they understand that a “one-size-fits-all” mentality doesn’t make good business sense when they’re trying to sell products in different markets, they’re willing to accommodate cultural and economic differences. Adaptation delivers a modified version of the product (may also modify promotional strategy and pricing) that considers local requirements, culturally and legally. Increasingly, MNCs supplement their mainstream product line with products designed for local markets.

Here are a few examples of product adaptation in foreign markets:

- Coca-Cola, for example, sells a coffee alternative and citrus-juice drinks developed specifically for the Japanese market.[33]

- McDonald’s adapts its menu for many global markets, retaining the same branding throughout yet bolstering the phrase ‘glocal’ through regional changes so you can enjoy Chicken McArabia in the Middle East, McSpaghetti in the Philippines, and Macarons in France.[34]

- Domino’s Pizza changed its toppings preferentially for local diners. They played to the popular diets of seafood and fish in Asia and curries in India.[35]

- Dunkin’ Donuts amends its menus to cater to each of the 36 countries where it operates. You might not instantly warm to the idea of a dry pork and seaweed donut, but they’re all the rage in China.[36]

- P&G Diapers completely remodelled its product when moving into alternative local markets. Their research into local markets found that many features weren’t considered necessary in poorer countries, and the price seemed to be the critical factor. So, by amending packaging and product materials, they managed to match the price point (to the same as a single egg) without damaging the brand.[37]

Self-Check Exercise: Tour of McDonald’s

Check your understanding of “Think globally, act locally” for McDonald’s MNC. Review each image and try to guess which country the McDonald’s meal is sold in. Hover your mouse over the image to get the answer.

Benefits of MNCs

Supporters of MNCs respond that huge corporations deliver better, cheaper products for customers everywhere; create jobs; and raise the standard of living in developing countries. They also argue that globalization increases cross-cultural understanding.

Some of the benefits of MNCs include:[38]

- Create wealth and jobs around the world. Inward investment by multinationals creates much-needed foreign currency for developing economies. They also create jobs and help raise expectations of what is possible.

- Their size and scale of operation enable them to benefit from economies of scale, enabling lower average costs and prices for consumers. This is particularly important in industries with very high fixed costs, such as car manufacture and airlines.

- Large profits can be used for research & development. For example, oil exploration is costly and risky; this could only be undertaken by a large firm with significant profit and resources. It is similar for drug manufacturers who need to take risks in developing new drugs.

- Ensure minimum standards. The success of multinationals is often because consumers like to buy goods and services where they can rely on minimum standards. i.e., if you visit any country, you know that the Starbucks coffee shop will give you something you are fairly familiar with. It may not be the best coffee in the district, but it won’t be the worst. People like the security of knowing what to expect.

- Products that attain global dominance have a universal appeal. McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, and Apple have attained their market share due to meeting consumer preferences.

- Foreign investments. Multinationals engage in Foreign direct investment. This helps create capital flows to poorer/developing economies. It also creates jobs. Although wages may be low by the standards of the developed world, they are better jobs than alternatives and gradually help to raise wages in the developing world.

- Outsourcing of production by multinationals enables lower prices; this increases disposable incomes of households in the developed world and enables them to buy more goods and services, creating new sources of employment to offset the lost jobs from outsourcing manufacturing jobs.

Criticisms of MNCs

The global reach of MNCs is a source of criticism as well as praise. Critics argue that they often destroy the livelihoods of home-country workers by moving jobs to developing countries where workers are willing to labour under poor conditions and for less pay. They also contend that traditional lifestyles and values are being weakened, and even destroyed, as global brands foster a global culture of American movies, fast food, and cheap, mass-produced consumer products. Still others claim that the demand of MNCs for constant economic growth and cheaper access to natural resources does irreversible damage to the physical environment. All these negative consequences, critics maintain, stem from the abuses of international trade—from the policy of placing profits above people, on a global scale.

Some of the criticisms of MNCs include:

- In the pursuit of profit, multinational companies often contribute to pollution and the use of non-renewable resources, which is putting the environment under threat. For example, some MNCs have been criticized for outsourcing pollution and environmental degradation to developing economies where pollution standards are lower.[39]

- Outsourcing to cheaper labour-cost economies has caused a loss of jobs in the developed world. This is an issue in the US, where many multinationals have outsourced production around the world.[40]

- MNCs possess substantial financial and technological resources, enabling them to dominate markets. This often leads to monopolistic or oligopolistic practices, pushing smaller, local businesses out of competition. For example, global retail giants have faced criticism for undermining small-scale retailers in developing countries, disrupting local economies and livelihoods.[41]

- MNCs are frequently criticized for repatriating their profits to their home countries rather than reinvesting them in the host nations. This practice can drain foreign exchange reserves in developing countries and limit the local economic benefits of their operations. Host economies often see minimal returns despite significant contributions to MNC revenues.[42]

- MNCs are often accused of exploiting natural resources in host countries without adequate regard for sustainability. Industries such as mining, oil extraction, and agriculture are particularly notorious for depleting resources and leaving host countries with long-term environmental degradation.[43]

The Global Business Environment

In the classic movie The Wizard of Oz, a magically misplaced Midwest farm girl takes a moment to survey the bizarre landscape of Oz and then comments to her little dog, “I don’t think we’re in Kansas anymore, Toto”. That sentiment probably echoes the reaction of many businesspeople who find themselves in the midst of international ventures for the first time. The differences between the foreign landscape and the one with which they’re familiar are often huge and multifaceted. Some are quite obvious, such as differences in language, currency, and everyday habits (say, using chopsticks instead of silverware). But others are subtle, complex, and sometimes even hidden.

Success in international business means understanding a wide range of cultural, economic, legal, and political differences between countries. Let’s look at some of the more important of these differences.

The Cultural Environment

The cultural environment is the set of factors that shape the way people interact with each other and their physical and social environment. Even when two people from the same country communicate, there’s always a possibility of misunderstanding. When people from different countries get together, that possibility increases substantially. Differences in communication styles reflect differences in culture: the system of shared beliefs, values, customs, and behaviors that govern the interactions of members of a society. Cultural differences create challenges to successful international business dealings. Let’s look at a few of these challenges.

Some social scientists argue that CQ (Cultural Quotient) is the new IQ (Intelligence Quotient) and that it is an even more important measure for determining professional success than smarts measured by traditional intelligence quotient tests. Review this article, “Increase Your Cultural Intelligence” for some tips on improving your cultural intelligence. Take this Test Your Cultural Intelligence quiz if you wish to know whether or not you have a high CQ.

Language

English is the international language of business. The natives of such European countries as France and Spain certainly take pride in their languages and cultures, but nevertheless, English is the business language of the European community.

Whereas only a few educated Europeans have studied Italian or Norwegian, most have studied English. Similarly, on the South Asian subcontinent, where hundreds of local languages and dialects are spoken, English is the official language. In most corners of the world, English-only speakers, such as most Canadians, have no problem finding competent translators and interpreters. So why is language an issue for English speakers doing business in the global marketplace? In many countries, only members of the educated classes speak English. The larger population, which is usually the market you want to tap, speaks the local tongue. Advertising messages and sales appeals must take this fact into account. More than one English translation of an advertising slogan has resulted in a humorous (and perhaps serious) blunder.

Here are a few advertisements that were lost in translation:

- In Belgium, the translation of the slogan of an American auto-body company, Body by Fisher, came out as Corpse by Fisher.

- Translated into German, the slogan, Come Alive with Pepsi became Come Out of the Grave with Pepsi.

- A U.S. computer company in Indonesia translated “software” as “underwear”.

- A German chocolate product called “Zit” didn’t sell well in the U.S.

- An English-speaking car wash company in Francophone Quebec advertised itself as a “lavement d’auto” or “car enema” instead of the correct “lavage d’auto.

- In the 1970s, General Motors’ Chevy Nova didn’t get on the road in Puerto Rico, in part because “nova” in Spanish means “it doesn’t go”.

Furthermore, relying on translators and interpreters puts you as an international businessperson at a disadvantage. You’re privy only to interpretations of the messages that you’re getting, and this handicap can result in a real competitive problem. Maybe you’ll misread the subtler intentions of the person with whom you’re trying to conduct business. The best way to combat this problem is to study foreign languages. Most people appreciate some effort to communicate in their local language, even on the most basic level. They even appreciate mistakes you make, resulting from a desire to demonstrate your genuine interest in the language of your counterparts in foreign countries. The same principle goes doubly when you’re introducing yourself to non-English speakers in Canada. Few things work faster to encourage a friendly atmosphere than a native speaker’s willingness to greet a foreign guest in the guest’s native language.

Time and Sociability

North Americans take for granted many of the cultural aspects of our business practices. Most of our meetings, for instance, focus on business issues, and we tend to start and end our meetings on schedule. These habits stem from a broader cultural preference: we don’t like to waste time. (It was an American, Benjamin Franklin, who coined the phrase “Time is money.”) This preference, however, is by no means universal. The expectation that meetings will start on time and adhere to precise agendas is common in parts of Europe (especially the Germanic countries), as well as in Canada, but elsewhere—say, in Latin America and the Middle East—people are often late to meetings.

High-Context and Low-Context Cultures

Don’t expect businesspeople from these regions—or businesspeople from most of Mediterranean Europe, for that matter—to “get down to business” as soon as a meeting has started. They’ll probably ask about your health and that of your family, inquire whether you’re enjoying your visit to their country, suggest local foods, and generally appear to be avoiding serious discussion at all costs. For Canadians, such topics are conducive to nothing but idle chitchat, but in certain cultures, getting started this way is a matter of simple politeness and hospitality.

High-context and low-context cultures refer to different approaches to communication: High-context cultures rely on implicit messages, body language, and context. High-context cultures are often found in Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America. Low-context cultures prioritize explicit verbal communication and clarity. Low-context cultures are typically associated with Western countries like the United States and Germany.

Different cultures have different communication styles—a fact that can take some getting used to. For example, degrees of animation in expression can vary from culture to culture. Southern Europeans and Middle Easterners are quite animated, favoring expressive body language along with hand gestures and raised voices. Northern Europeans are far more reserved. The English, for example, are famous for their understated style and the Germans for their formality in most business settings. In addition, the distance at which one feels comfortable when talking with someone varies by culture. People from the Middle East like to converse from a distance of a foot or less, while North Americans prefer more personal space.

While people in some cultures prefer to deliver direct, clear messages, others use language that’s subtler or more indirect. North Americans and most Northern Europeans fall into the former category and many Asians into the latter. But even within these categories, there are differences. Though typically polite, Chinese and Koreans are extremely direct in expression, while Japanese are indirect: They use vague language and avoid saying “no” even if they do not intend to do what you ask. They worry that turning someone down will result in their “losing face”, i.e., an embarrassment or loss of credibility, and so they avoid doing this in public.

In summary, learn about a country’s culture and use your knowledge to help improve the quality of your business dealings. Learn to value the subtle differences among cultures, but don’t allow cultural stereotypes to dictate how you interact with people from any culture. Treat each person as an individual and spend time getting to know what he or she is about.

Self-Check Exercise: Globalization Quiz

Check your understanding of this chapter’s global business concepts. Complete this quiz.

The Economic Environment

Economic development refers to the process through which a region, country, or community improves the well-being of its citizens by increasing income, reducing poverty, creating jobs, and expanding access to healthcare and education. If you plan to do business in a foreign country, you need to know its level of economic development. You also should be aware of factors influencing the value of its currency and the impact that changes in that value will have on your profits.

Economic Development

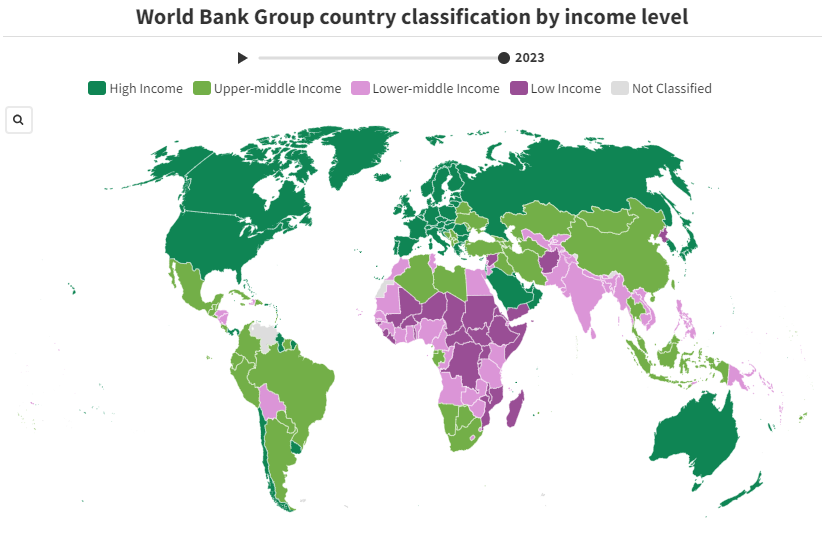

If you don’t understand a nation’s level of economic development, you’ll have trouble answering some basic questions, such as: Will consumers in this country be able to afford the product I want to sell? Will it be possible to make a reasonable profit? A country’s level of economic development can be evaluated by estimating the annual income earned per citizen. The World Bank, which lends money for improvements in underdeveloped nations, divides countries into four income categories (Refer to Figure 7.4):

World Bank Group Income Categories as of July 1, 2024:[44]

- High income—Greater than $14,005 or higher (United States, Germany, Japan, Canada)

- Upper-middle income—$4,516 to $14,005 (China, South Africa, Mexico)

- Lower-middle income—$1,146 to $4,515 (Kenya, Philippines, India)

- Low income—$1,145 or less (Afghanistan, South Sudan, Uganda)

Note that even though a country has a low annual income per citizen, it can still be an attractive place for doing business. India, for example, is a lower-middle-income country, yet it has a population of a billion, and a segment of that population is well educated—an appealing feature for many business initiatives.

The classification of countries into income categories has evolved significantly over the period since the late 1980s. In 1987, 30% of reporting countries were classified as low-income and 25% as high-income countries. Jumping to 2023, these overall ratios have shifted down to 12% in the low-income category and up to 40% in the high-income category.

The scale and direction of these shifts, however, vary a great deal between world regions. Here are some regional highlights:[45]

- 100% of South Asian countries were classified as low-income countries in 1987, whereas this share has fallen to just 13% in 2023.

- In the Middle East and North Africa, there is a higher share of low-income countries in 2023 (10%) than in 1987, when no countries were classified to this category.

- In Latin America and the Caribbean, the share of high-income countries has climbed from 9% in 1987 to 44% in 2023.

- Europe and Central Asia have a slightly lower share of high-income countries in 2023 (69%) than it did in 1987 (71%).

The long-term goal of many countries is to move up the economic development ladder. Some factors conducive to economic growth include a reliable banking system, a strong stock market, and government policies to encourage investment and competition while discouraging corruption. It’s also important that a country have a strong infrastructure—its systems of communications (telephone, Internet, television, newspapers), transportation (roads, railways, airports), energy (gas and electricity, power plants), and social facilities (schools, hospitals). These basic systems will help countries attract foreign investors, which can be crucial to economic development.

Currency Valuations and Exchange Rates

If every nation used the same currency, international trade and travel would be a lot easier. Of course, this is not the case. The United Nations currently recognizes 180 currencies that are used in 195 countries across the world.[46] Some currencies you’ve heard of, such as the British pound; others are likely unknown to you, such as the manat, the official currency of Azerbaijan. If you were in Azerbaijan, you would exchange your Canadian dollars for Azerbaijan manats. The day’s foreign exchange rate will tell you how much one currency is worth relative to another currency and so determine how many manats you will receive. If you have traveled abroad, you already have personal experience with the impact of exchange rate movements.

The Legal and Regulatory Environment

One of the more difficult aspects of doing business globally is dealing with vast differences in legal and regulatory environments. Canada, for example, has an established set of laws and regulations that provide direction to businesses operating within its borders. But because there is no global legal system, key areas of business law—for example, contract provisions and copyright protection—can be treated in different ways in different countries. Companies doing international business often face many inconsistent laws and regulations. To navigate this sea of confusion, Canadian business people must know and follow both Canadian laws and regulations and those of nations in which they operate.

Business history is filled with stories about North American companies that have stumbled in trying to comply with foreign laws and regulations. Laws change as well over time. For example, the government in the Netherlands made working from home a legal right. This means companies can expect requests from employees to work remotely, therefore, companies should develop a work-from-home policy outlining the factors they will consider when an employee makes a request.[47]

One approach to dealing with local laws and regulations is to hire lawyers from the host country who can provide advice on legal issues. Another is working with local business people who have experience in complying with regulations and overcoming bureaucratic obstacles.

Foreign Corrupt Practices Act

One Canadian law that creates unique challenges for Canadian firms operating overseas is the Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act (CFPOA), which prohibits the distribution of bribes and other favors in the conduct of business. Despite the practice being illegal in Canada, such tactics as kickbacks and bribes are business-as-usual in many nations. According to some experts, Canadian business people are at a competitive disadvantage if they’re prohibited from giving bribes or undercover payments to foreign officials or business people who expect them. In theory, because the Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act warns foreigners that Canadians can’t give bribes, they’ll eventually stop expecting them.

Where are business people most likely and least likely to encounter bribe requests and related forms of corruption? Transparency International reports on corruption and publishes an annual Corruption Perceptions Index that rates the world’s countries. Transparency International annually rates nations according to “perceived corruption” and defines corruption as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain.” A score of 100 would be perfect (corruption-free) and anything below 30 establishes that corruption is rampant. In 2024, Canada scored 75/100 on the Corruption Perceptions Index, ranking 15/180 countries. Top-scoring countries also tend to have well-functioning justice systems, stronger rule of law, and political stability.[48]

Ranked as the least corrupt country was Denmark, ranking 1/180 and scoring 90/100, followed by Finland, Singapore, New Zealand, Luxembourg, Norway, Switzerland, and Sweden. The most corrupt countries include South Sudan, ranked 180/180, followed by Somalia, Venezuela, Syria, Yemen, Libya, and Eritrea.[49]

Transparency International reports on corruption and publishes an annual Corruption Perceptions Index that rates the world’s countries. A score of 100 would be perfect (corruption-free), and anything below 30 establishes that corruption is rampant.

Trade Controls

The debate about the extent to which countries should control the flow of foreign goods and investments across their borders is as old as international trade itself. Trade controls are policies that restrict free trade, and governments continue to control trade. To better understand how and why, let’s examine a hypothetical case. Suppose you’re in charge of a small country in which people do two things—grow food and make clothes. Because the quality of both products is high and the prices are reasonable, your consumers are happy to buy locally made food and clothes. But one day, a farmer from a nearby country crosses your border with several wagonloads of wheat to sell. On the same day, a foreign clothes maker arrives with a large shipment of clothes. These two entrepreneurs want to sell food and clothes in your country at prices below those that local consumers now pay for domestically made food and clothes. At first, this seems like a good deal for your consumers: they won’t have to pay as much for food and clothes. But then you remember all the people in your country who grow food and make clothes. If no one buys their goods (because the imported goods are cheaper), what will happen to their livelihoods? And if many people become unemployed, what will happen to your national economy? That’s when you decide to protect your farmers and clothes makers by setting up trade rules. Maybe you’ll increase the prices of imported goods by adding a tax to them; you might even make the tax so high that they’re more expensive than your homemade goods. Or perhaps you’ll help your farmers grow food more cheaply by giving them financial help to defray their costs. The government payments that you give to the farmers to help offset some of their costs of production are called subsidies. These subsidies will allow the farmers to lower the price of their goods to a point below that of imported competitors’ goods. What’s even better is that the lower costs will allow the farmers to export their goods at attractive, competitive prices.

Canada has a long history of subsidizing farmers. Subsidy programs guarantee farmers (including large corporate farms) a certain price for their crops, regardless of the market price. This guarantee ensures stable income in the farming community, but it can have a negative impact on the world economy. How? Critics argue that in allowing Canadian farmers to export crops at artificially low prices, Canadian agricultural subsidies permit them to compete unfairly with farmers in developing countries. A reverse situation occurs in the steel industry, in which a number of countries—China, Japan, Russia, Germany, and Brazil—subsidize domestic producers. U.S. trade unions charge that trade subsidy practices give an unfair advantage to foreign producers and hurt American industries, which can’t compete on price with subsidized imports.

The top exports of Canada in 2022 were Crude Petroleum ($123B), Cars ($29.4B), Petroleum Gas ($24.3B), Refined Petroleum ($17.2B), and Gold ($14.7B), exporting mostly to United States ($438B), China ($25.4B), Japan ($14.3B), United Kingdom ($12.9B), and Mexico ($7.39B). The top imports of Canada are Cars ($31.9B), Refined Petroleum ($19.8B), Motor vehicles; parts and accessories (8701 to 8705) ($17.4B), Delivery Trucks ($17.3B), and Crude Petroleum ($16.8B), importing mostly from United States ($308B), China ($62.1B), Mexico ($22.2B), Germany ($14.1B), and Japan ($9.87B).[50] So, if Canada imported $308B from the United States and exported $438B to the United States, Canada achieved a positive trade balance of $130B.

Whether they push up the price of imports or push down the price of local goods, such initiatives will help locally produced goods compete more favorably with foreign goods. Both strategies are forms of trade controls—policies that restrict free trade. Because they protect domestic industries by reducing foreign competition, the use of such controls is often called protectionism. Though there’s considerable debate over the pros and cons of this practice, all countries engage in it to some extent. Before debating the issue, however, let’s learn about the more common types of trade restrictions: tariffs, quotas, and embargoes.

Tariffs

Tariffs are taxes on imports. Because they raise the price of the foreign-made goods, they make them less competitive. Tariffs are also used to raise revenue for a government. Donald Trump, President of the United States, for example, announced in March of 2018 that the U.S. would increase tariffs on imported steel products from 10% to 25% as a means of enhancing the American steel industry and protecting U.S steel manufacturers.

Quotas

A quota imposes limits on the quantity of a good that can be imported over a period of time. Quotas are used to protect specific industries, usually new industries or those facing strong competitive pressure from foreign firms. Canadian import quotas take two forms. An absolute quota fixes an upper limit on the amount of a good that can be imported during the given period. A tariff-rate quota permits the import of a specified quantity and then adds a high import tax once the limit is reached.

Sometimes quotas protect one group at the expense of another. For example, let us assume that a hypothetical country restricts the number of mangoes imported. If the demand for mangoes in the country is 27,000 pounds, and the current international market price for one pound of mangoes is $1.35. Upon introducing an import quota, the country imposes restrictions and allows importing only 18000 pounds of mangoes. When this happens, it hikes the domestic price to $1.89 per pound of mangoes. At this price, the domestic farmers of the country can afford to increase their production from 4000 to 9000 pounds. At the same time, at the price of $1.89 per pound, the country’s demand for mangoes declines to 25000 pounds. In this example, the restriction helps domestic mango farmers increase production and decrease demand through price regulation.[51]

Another example, the wheat export quota implemented by India, has prompted Nepal’s flour industry to adapt and innovate. It was introduced in response to concerns about reduced wheat production due to heatwaves in India, but it has spurred resilience in Nepali flour mills. Nepal, which primarily sources wheat from India, initially received a partial quota allocation, leading to concerns about potential price increases. In response to this situation, calls have been made for the Nepali government to engage in constructive dialogue with India to secure 200,000 tonnes of wheat, which could help mitigate potential shortages. While the initial quota allocation did offer some relief by reducing flour prices, industry leaders are now advocating for a comprehensive, long-term solution, recognizing that domestic production alone may not suffice to meet the demand.[52]

Embargos

An extreme form of quota is the embargo, which, for economic or political reasons, bans the import or export of certain goods to or from a specific country.

Dumping

A common political rationale for establishing tariffs and quotas is the need to combat dumping: the practice of selling exported goods below the price that producers would normally charge in their home markets (and often below the cost of producing the goods). Usually, nations resort to this practice to gain entry and market share in foreign markets, but it can also be used to sell off surplus or obsolete goods. Dumping creates unfair competition for domestic industries, and governments are justifiably concerned when they suspect foreign countries of dumping products on their markets. They often retaliate by imposing punitive tariffs that drive up the price of the imported goods.

The Pros and Cons of Trade Controls

Opinions vary on government involvement in international trade. Proponents of controls contend that there are a number of legitimate reasons why countries engage in protectionism. Sometimes they restrict trade to protect specific industries and their workers from foreign competition—agriculture, for example, or steel making. At other times, they restrict imports to give new or struggling industries a chance to get established. Finally, some countries use protectionism to shield industries that are vital to their national defense, such as shipbuilding and military hardware.

Despite valid arguments made by supporters of trade controls, most experts believe that such restrictions as tariffs and quotas, as well as practices that don’t promote level playing fields, such as subsidies and dumping, are detrimental to the world economy. Without impediments to trade, countries can compete freely. Each nation can focus on what it does best and bring its goods to a fair and open world market. When this happens, the world will prosper, or so the argument goes. International trade is certainly heading in the direction of unrestricted markets.

Reducing International Trade Barriers