ESTABLISHING A POSITIVE LEARNING ENVIRONMENT

20 Navigating Difficult Conversations for Inclusion and Equity

Difficult conversations on challenging topics are often uncomfortable for educators and students. However, having difficult conversations as part of our teaching can help improve critical thinking skills and can assist in fostering a more inclusive educational environment. This workshop explores the potential of engaging students in challenging conversation -we will discuss the importance of multiple perspectives in teaching and pedagogical approaches to challenging topics in the classroom.

In this chapter, you will

- Gain a deeper understanding of positionality and its impact on conversations.

- Recognize the importance of the TA’s role in navigating challenging dialogues and creating an inclusive environment.

- Appreciate the potential benefits and opportunities for growth that difficult conversations can offer.

Difficult Conversations in Educational Settings

Before talking about strategies, let’s consider your ideas about difficult conversations that arose from class content or reactions to the content presented in a class:

Consider questions like:

- What does a difficult conversation look or sound like?

- What course content has arisen for you that made for a difficult conversation?

- What kind of difficulties have you faced when trying to navigate difficult conversations?

- What strategies have you used and did these change depending on the topic?

- Were you ever surprised in a difficult conversation?

- Looking ahead to teaching you will be doing, can you identify potential difficult conversation moments that might arise?

What makes conversations in our classes difficult?

Difficult conversations are an inescapable part of higher education. In a classroom, you can expect to find a diversity of experiences, interests and knowledge. These all add to the richness of the learning experience. As an instructor, we can anticipate critical conversations in our learning environments and strategically utilize these as teachable moments. Often, it is the role of the instructor to guide students in exploring “hot button” issues, but leading these discussions is a perennial challenge.

Part of the challenge lies in the fact that we never fully know which issues will be “hot buttons” for our students. Similarly, because we all have our own lived experiences, we will all have topics, ideas, and issues that will be particularly difficult to navigate.

“Know yourself. Know your biases, know what will push your buttons and what will cause your mind to stop. Every one of us has areas in which we are vulnerable to strong feelings. Knowing what those areas are in advance can diminish the element of surprise. This self-knowledge can enable you to devise in advance strategies for managing yourself and the class when such a moment arises. You will have thought about what you need to do in order to enable your mind to work again”

Lee Warren (Derek Bok Center, Harvard), “Managing Hot Moments in the Classroom”

Types of Difficult Conversations

Planned Discussions are scheduled, content-specific, emerging from learning material, or guided by exploration of a topic. These are typically anticipated and you can prepare for them in advance.

Unplanned Discussions are often spur-of-the-moment. These discussions are student initiated, and topical and/or situation. Unplanned discussions may occur because of events or circumstances outside of the classroom (e.g. political moments, trauma, environmental events) and can range from the individual to the global level. How these discussions arise can vary.

Consider the following video. Can you pick out examples of which difficult discussions could have been anticipated by the instructor/TA based on the course content and which would have been unplanned?

Reflecting on our own Identities

Reflecting on our own lived experiences and intersectional identities (the socio-cultural ways we identify race, class, gender identity, disability, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation) is a good place to contextually start working to support difficult conversations . Having an awareness of positionality can better prepare you for potentially difficult conversations in the educational space.

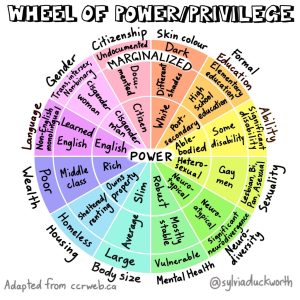

This is Sylvia Duckworth’s Wheel of Privilege. [3]

Text for the wheel of power and privilege:

A circle chart showing the different power and privilege positions as drawn by Sylvia Duckworth based on information from Canadian Council of Refugees. The areas of the circle are the following where the last positionality of each area is the positionality with power.

Wealth: poor, middle class, rich

Housing: Homeless, renting, owns property

Body size: large, average, slim

Mental health: Vulnerable, mostly stable, robust

Neuro-diversity: Significant neurodivergence, neuro-atypical, neurotypical

Sexuality: lesbian bi pan asexual, gay men, heterosexual

Ability: significant disability, some disability, able-bodied

Formal education: elementary, high school, post-secondary

Skin colour: dark, different shades, white

Citizenship: undocumented, documented, citizen

Gender: Trans intersex non-binary, cisgender woman, cisgender man

Language: non-English monolingual, learned English, English

(Duckworth, 2020) Image Description (Doc)![]() [4]

[4]

The activity below shows the twelve social identity categories by Sylvia Duckworth. Think about how you define yourself. In each category, click on ONLY ONE of the three sections that reflect your identity. The closer you are to the right you are closer to power and privilege.

Define Yourself

In this topic, we hope you learned about yourself, your salient social identities, and how they interact with the systems of power and oppression in our society. To conclude, we invite you to think about your social location and the intersecting identities which shape your interactions within the higher education system. How are these similar and different to your colleagues, students, and administrators? How has academia epistemically favoured scholarship and ways of knowing of those with identities closer to the centre of power? Which social identities do the systems of power historically (and currently) serve?

Referring back to the identities in the Wheel of Power/Privilege think about how you define yourself, and where your salient social identities are located on the wheel. Get curious about:

- How close or far away from the centre are you?

- How does your level of power shift as you place yourself in different identity categories?

- Thinking about your institution, where do students, staff, administrators, and/or faculty reside?

You are invited to record your reflection in the way that works best for you, which may include writing, drawing, creating an audio or video file, mind map or any other method that will allow you to document your ideas and refine them at the end of this module.

Alternatively, a text-based note-taking space is provided below. Any notes you take here remain entirely confidential and visible only to you. Use this space as you wish to keep track of your thoughts, learning, and activity responses. Download a text copy of your notes before moving on to the next page of the module to ensure you don’t lose any of your work!

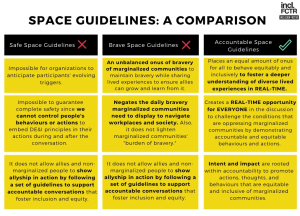

Safe, Brave and Accountable spaces

There has been much discussion amongst educators about creating spaces for difficult conversations and dialogue in the variety of classroom spaces now available to us. This section attempts to summarize some of these ideas and tensions about the kinds of spaces we create for learners to engage with difficult conversations.

Safe Spaces

Safe space can imply that danger, risk, or harm will not occur in the learning environment. To claim we can create “safe spaces” is misleading and counterproductive because it promises to protect and exempt people from the very real learning and growth required. Elise Ahenkorah (2020) states “…safe spaces don’t exist for equity-deserving communities – or those learning about identity and privilege.” Ahenkorah is drawing attention to the necessary and daily work of the lived experience of many individuals in equity deserving communities.

Brave Spaces

Brave Spaces shift away from the concept of safety and emphasize the importance of bravery instead, to help students better understand—and rise to—the challenges of genuine dialogue on diversity and social justice issues. “[U]sing ‘brave’ rather than ‘safe’ not only sets a tone for engagement but also proposes a mode of engagement” (Cook-Sather, 1). Painful or difficult experiences in “brave spaces” are acknowledged and supported, not avoided or eliminated. “[C]reating brave spaces [can] challenge the implicit and explicit ways in which inclusion and exclusion, affirmation and disenfranchisement, and belonging and alienation play out for people with different identities” (Cook-Sather, 2).

But brave spaces can place a lot of pressure and accountability on the people who have to be brave, be repeatedly brave. Ahenkorah states brave spaces “…negate the daily bravery marginalized communities need to display everywhere, to navigate everyday and common biases, discriminate, and microaggressions…”

Accountable Spaces

Higher education learning environments in all disciplines often require learners to engage with uncomfortable subject matter, controversies, and challenges to previously held ideas, ideologies, and values. Developing an environment where learners can feel like they are willing to step outside comfort zones, embrace the challenge, sit with discomfort and in the process learn, means that the space may better be described, as Ahenkorah does, as “accountable spaces”. “Accountablility means being responsible for yourself, your intentions, words and actions”(Ahenkorah, 2020). This means being open to how words and actions are received, even if negatively. “It means entering a space with good intentions, but understanding that aligning your intent with action is the true test of commitment” (Ahenkorah, 2020)

Summary of chart:

Suspending Judgment in Conversation, A Model

There are different strategies and tools that you can use in your pedagogy to support difficult conversations when they arise. Remember that all teaching tools and strategies are contextual, and will depend on the space you are in, who is present for the conversation, and what the conversation is about.

Use observe, describe, interpret, suspend evaluation (ODIS) method to suspend judgment (and teach it to the students).

Applying ODIS Method to Suspend Judgement

| Observe | Observe an interaction, especially verbal and non-verbal communication. |

| Describe | Describe what is going on in the interaction (e.g., “He does not maintain eye contact with me when speaking to me.”). |

| Interpret | Generate multiple interpretations to “make sense” of the behaviour. For Example: “Maybe from their cultural framework, avoiding eye contact is what people do to show respect; but from my cultural point of view, this is considered disrespectful.” Or “Maybe eye contact from their lived experience is difficult or painful; but from my neurotypical point of view I need eye contact to know they are listening to me.” |

| Suspend Evaluation | Respect the differences and suspend an evaluation, or engage in an open-ended evaluation by acknowledging how an unfamiliar behaviour makes us feel (e.g. “I understand that eye contact avoidance may be a cultural habit of this person, or perhaps it is a method of coping with a disability, no matter what, I can recognize we have this difference and we can come to the conversation about it together.”). |

Using the O.D.I.S. analysis allows us to have an honest, reflective dialogue with ourselves and helps us become more aware of our automatic reactions and emotions.

Strategies to Prepare for Difficult Conversations

While you can anticipate that some discussions may lead to challenging moments, every class has the potential to include difficult conversations. These strategies can be considered when you know that you will be facilitating a difficult conversation in class or online but also as you prepare yourself and your students for having discussions regardless of the topic.

Preparing Yourself

- Remind yourself of the learning outcomes for the course and this particular class. What are students expected to learn from the discussions? Consider making these explicit (in writing and out loud) to students at the beginning of the class.

- Thoughtfully consider how you want to organize the discussion. Consider:

- What questions/prompts should be for individual student reflection and which should be opened for larger discussions?

- Would the discussions be best conducted in a large group, smaller groups, or a combination? How will you mediate these?

- If you are going to put students in groups how will these be determined?

- If you are teaching in-person, how will you arrange the classroom (if it can be altered)? For example: how is the physicality of the room going to impact learning? Is there an obvious hierarchy? Is a circle (less hierarchical) possible?

- If you are teaching synchronously on-line, how will you manage the communication elements like chat features, attaching files, taking over the screen, muting complications (muting or unmuting inappropriately).

- If you are teaching asynchronously, how will you manage posted inappropriate material or comments? How will you insert yourself into conversations that are becoming challenging?

- If you are responsible for ‘participation’ or ‘discussion’ grading, consider what aspects of the class will be for grades and which ones might not be (if you have this freedom). Can students have multiple options for participating (e.g. individual reflection, summary of small group discussion, participating in large discussion) instead of marks only being associated with group discussions where some students may feel more or less comfortable contributing? Make these decisions explicit to students at the outset of the class, particularly if they deviate from the normal convention.

Preparing your students

- Throughout the term cultivate a respectful learning community and offer opportunities for students to build rapport with each other. Consider some of the community building learning activities developed by Equity Unbound and OneHE for ideas and strategies you can use with your in-person, blended, or online course.

- Co-construct a framework/guidelines for an accountable space with your students. Offer opportunities for them to reflect on what an accountable space looks, feels, and sounds like and then work together to craft a set of ‘ground rules’. Make sure that these are available to students in writing and revisit them at the beginning of discussions, whether you anticipate that they will be difficult or not. For more resources, visit Chapter 11: Setting Ground Rules.

- Warm up and offer opportunities to learn how to have a respectful dialogue. Create opportunities to practice having discussions that aren’t as complex on topics that aren’t potentially as emotionally-charged, rather than expecting students to learn these skills in the midst of a ‘hot button’ issue.

- Make explicit any disciplinary models for thinking/engaging that are expected of them in the course. For example, is there a certain level of evidence that is expected to be applied to their reasoning or certain theories/concepts that they should be explicitly applying?

- Provide forewarning that the content in upcoming discussions may be challenging. Be candid that the discussions may be difficult, awkward, or challenging, but also provide a rationale for why these discussions are important parts of the course. Connect back to the course learning outcomes (they are often included in the course syllabus) to demonstrate this. Offer ‘content warnings’ rather than ‘trigger warnings’ to provide an overview of the content rather than assuming how students may (or may not) feel about it. For example, “Next week we will be talking about residential schools and viewing a film that details the experiences of two survivors” gives students insight, whereas a ‘trigger warning such as “Some of you might find next week’s material distressing.” includes assumptions about our students and the nature of the learning that will occur.

- If permitted, offer students the discussion questions in advance so that they have time to think and reflect on them and prepare before class or at the beginning of class. This practice gives students opportunity to consider their viewpoints, familiarize themselves with a topic, and have some ideas prepared ahead of time. It can also help curb feelings of being ‘put on the spot’, and anxiety that can be counterproductive to learning.

Navigating Planned Conversations with Difficult Content

You may worry or wonder about beginning a discussion about a challenging topic and what to do if students remain silent. The answer is, allow for silence. Give students time to reflect and get ready to speak. If the silence persists, consider asking students to write out a few thoughts or use a Think, Pair, Share strategy of sharing in pairs or small groups and then sharing back to the larger group to revisit the question and discuss as a class.

In Brian Arao and Kristi Clemens’s (2013) work, they state, “the practice of establishing ground rules or guidelines for conversations and behaviour is foundational to diversity and social justice learning activities” (135). Re-framing ground rules to establish an Accountable space is an asset to facilitators engaged in social justice work. It helps to better prepare participants to interact authentically with one another in challenging dialogues.

Things to consider for developing accountable spaces for difficult conversations:

- Set the tone, refer back to community agreements or first class agreements about ways of being and communicating in class. Include statements agreeing that all people in the class are learning.

- Set a structure for one person to speak at a time and clearly state interruptions are not welcome. Model and articulate what active listening looks and sounds like. Active listening is not just waiting to speak, encourage students to write thoughts down if they have the desire to interrupt.

- Everyone should have a chance to speak or express int he way that might be best for them. Reading out what a student has written can help with confidence and the consideration of words.

- Be mindful of total talk time. Encourage students to ask questions that can help the conversation move forward (e.g. finishing the statement “Have you ever thought about….”?).

- If you said something offensive or problematic, apologize for your actions or words being offensive, avoiding including “you” and “but” statements. Remember that intent is not always reflective of the impact your words or actions may have.

- Recognize and embrace friction as evidence that multiple ideas are entering the conversation — not that the group is not getting along.

- Give credit where it is due. If you are echoing someone’s previously stated idea, give the appropriate credit. Ethical citational practices help support communities of learners and opens up space for ideas and following other’s thoughts.

- Speak for yourself and encourage learners to use “I” statements and not speak for others’ lived experiences. Consider asking yourself and your learners what unspoken privileges those “I” statements might come with if you are not part of a marginalized or equity diverse group.

- Words and tone matter. Be mindful of the impact of what you say, and not just your intent.

- Allow space for equity-deserving and marginalized communities to share their experiences. Believe them. Just because your experience has been different does not mean that other’s experiences are invalid.

Support for After the Conversation

What if a class ends and things seem unresolved? What should I do? You can ask for exit notes from the students at the end of class for feedback, and check in either in person or by email with certain students who seemed particularly upset. It will be important to resolve any remaining concerns at the beginning of the next class session.

Consider the following:

- After leaving the class, reflect on how the conversation went, both your part as facilitator and what the students said. What went well, what didn’t go well, what you might do in a future instance.

- Reflect on whether anything seems unfinished and consider how to address that feeling.

- Offer opportunities for reflection / debrief with the class (individual, group, with instructor; online, in-class, asynchronously). Revisit the class ground rules/framework for respectful discussions to determine if anything needs to be reviewed, added, or changed

- Acknowledge the challenges of uncomfortable conversations / offensive comments, including how you felt in that moment.

- Mindfully and equitably hold space for those who are most impacted by the conversation / comments (ie, equity-denied students)

- Consider actionable items to become an ally: how can you use or apply what you have learned? Don’t place the burden of educating the whole class on those from equity-deserving communities.

- Refer students to campus supports as appropriate.

Further Resources

- Arao, B. & Clemens, K. in the Landreman, From Safe Spaces to Brave Spaces in L. M. (Ed.). (2013). The art of effective facilitation : Reflections from social justice educators. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

- Delano-Oriaran, O. O., & Parks, M. W. (2015). One Black, one White: Power, White privilege, & creating safe spaces. Multicultural Education, 22, 15-19.

- Housee, S. (2008). Should ethnicity matter when teaching about “race” and racism in the classroom? Race, Ethnicity and Education, 11(4), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613320802478960

- Thurber, A., Harbin, M.B., & Bandy, J. (2019). Teaching Race: Pedagogy and Practice. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved [todaysdate] from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/teaching-race/.

- Kumashiro, K. K. (2000). Toward a Theory of Anti-Oppressive Education. Review of Educational Research, 70(1), 25–53. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070001025

- Leonardo, Z., & Porter, R. K. (2010). Pedagogy of fear: toward a Fanonian theory of “safety” in race dialogue. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 13(2), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2010.482898

- Navigating Difficult Conversations in the Classroom (PDF Resource)

- Navigating Difficult Conversations

- Navigating Microagressions in Online Learning

- Teaching During Global and Geopolitical Crisis

- Safe and Brave Spaces Don’t Work and What You Can Do Instead

- Adapted from Queen's University "Navigating Difficult Conversations" Module. ↵

- DesRochers, J. Chapter 6: Navigating Difficult Conversations: Strategies for Equitable and Inclusive Engagement. In Designing for Meaningful Synchronous and Asynchronous Discussions in Online Courses. Queen's University. ↵

- Wheel of Privilege and Power: Sylvia Duckworth ↵

- Adapted from DesRochers, J. Chapter 6: Navigating Difficult Conversations: Strategies for Equitable and Inclusive Engagement. In Designing for Meaningful Synchronous and Asychronous Disucssion in Online Courses. Queen's University. ↵

- Adapted from: Universal Design for Learning (UDL) for Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility (IDEA) by Darla Benton Kearney ↵

- AFS Intercultural Programs. Series #18. ↵

- Sources: Navigating Difficult Conversations: Strategies for Equitable and Inclusive engagement by Jacob DesRochers, Queen’s University Managing Difficult Classroom Discussions- Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning - Indiana University Bloomington ↵

- Adapted from: Koopman, Sara & Knight, Kristina. (2019). Teaching Tools in a Flash - Navigating Difficult Conversations in the Classroom. Ahenkorah, E. (2020). Safe and Brave Spaces Don't Work (and What you can do instead). ↵

- Adapted from: Igobwa, E. & Penney, M. (2023). Public-Facing Resource: Teaching During Global and Geopolitical Crisis. University of Alberta. Koopman, Sara & Knight, Kristina. (2019). Teaching Tools in a Flash - Navigating Difficult Conversations in the Classroom. ↵