PREPARING AND TEACHING

11 Facilitating Discussion

…high-quality classroom talk enhances understanding, accelerates learning and raises learning outcomes”

(Hattie, 2009 in Hardman, 2016, p. 64)

Facilitating discussions is an important skill for teaching assistants. In this chapter, we will explore some approaches to facilitating discussions, discuss some important elements of the process of developing points/questions for discussion, and creating/keeping engagement.

This chapter’s learning outcomes include:

- Develop an understanding of:

- the role discussions play in teaching and learning in the university classroom;

- the various types of questions;

- and how different types of questions can be utilized in the facilitation of discussion

- Using questions to facilitate discussion

- Understanding the role instructors/TAs play in facilitating robust discussion

USING QUESTIONS TO FACILITATE DISCUSSION

To question well is to teach well. In the skillful use of the question more than anything else lies the fine art of teaching; for in it we have the guide to clear and vivid ideas, the quick spur to imagination, the stimulus to thought, the incentive to action.”

– Charles Degarmo (1911)

Often times, questions are used as a starting point for discussions within the university classroom. You may use questions related to lecture content, reading materials, course activities, or even material related to course assignments.

Developing and asking questions that support productive and critical discussion is no easy task! It is important to carefully craft questions that support student engagement, critical thinking, collaboration, and dialogue.

We will now start to explore how you can develop high quality and effective questions to support discussion in your classroom.

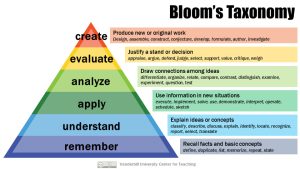

BLOOM’S TAXONOMY

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a classification system that can be used to organize the skills and objectives set within a course, unit, or lesson.

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a hierarchical system – this means that in order to achieve the learning or skills positioned higher within the hierarchy the knowledge/skills at the lower levels must be accomplished first.

BLOOM’S TAXONOMY: COGNITIVE DOMAIN

Bloom’s taxonomy positions remembering as lower-level thinking. Though it is classified as “lower-level” it is not unimportant as remembering is crucial to understanding and progression towards higher-level thinking. The description provided here (in both the image and the text) are attributed to the Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching.

These descriptions described the revised taxonomy proposed by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001).

- Remember: Recall facts and basic concepts (define, duplicate, list, memorize, state, repeat)

- Understand: Explain ideas or concepts (classify, describe, discuss, explain, identify, locate, recognize, report, select, translate)

- Apply: Use information in new situations (execute, implement, solve, use, demonstrate, interpret, operate, schedule, sketch)

- Analyze: Draw connections among ideas (differentiate, organize, relate, compare, contrast, distinguish, examine, experiments question, test)

- Evaluate: Justify a stand or a decision (appraise, argue, defend, judge, select, support, value, critique, weigh)

- Create: Produce new or original work (Design, assemble, construct, conjecture, develop, formulate, author, investigate)

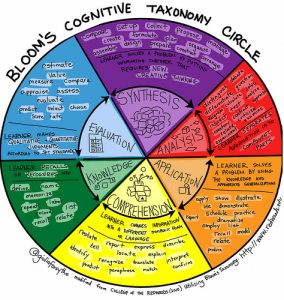

Critics of Bloom’s Taxonomy, however, question the linear progression through knowledge acquisition and skill development from lower-to-higher order thinking. Below is an image by Giulia Forsythe which reconceptualizes Bloom’s Cognitive Taxonomy as a circle.

THE QUESTIONING MATRIX

As you prepare to facilitate discussions it is also important to recognize and consider the types of questions you are posing to students and how they relate to the types of knowledge and skills described via Bloom’s Taxonomy.

To do so, consider the following:

- Is the question open (allowing for multiple answers) or closed (yes/no or stated fact response)?

- What is the question asking students to do (e.g. define, paraphrase, evaluate, etc.)?

Determining the question type (open or closed) and what the question asks students to do (relationship to Bloom’s Cognitive Taxonomy) can help you to understand if the questions you ask are likely to yield the kinds of responses and discussion you hope. That is, if you want to check for understanding a closed, knowledge or comprehension based question may serve your purpose well. But if you want to spark a class dialogue on a course content or a class reading, for example, you will need to ask an open-ended question that asks students to demonstrate evaluation, application, synthesis, or analysis.

The Questioning Matrix can help you to develop questions that spark, promote, and extend discussion among your students.

Please find Questioning Matrix Downloadable File

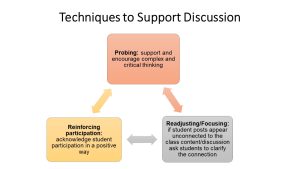

Techniques to Support Discussions

Three techniques to support discussion in your classroom include:

- Reinforcing student participation: encouraging students to continue contributing to class discussion by acknowledging their contribution

- Probing: supporting students towards more complex and critical engagements by asking questions that extend the discussion

- Focusing: at times discussion may seem disconnected to course goals/content you can re-focus the discussion by asking students to clarify the connections between the discussion and course content and encouraging the discussion to stay “on track.”

The seminar leader should respond to students’ answers in such a way as to encourage participation. This is crucial since your response will probably influence both the student offering the comment and those observing the interaction. In many seminars, students are asked to engage in discussion about a topic/idea/reading/method and there are many activating topics (political, emotional, etc.) that must be discussed in a university classroom. Facilitating these discussions can be difficult.

For more information on facilitating difficult discussions, check out Navigating Difficult Conversations chapter.

Suggestions when facilitating discussions

Here’s some suggestions when facilitating discussions:

- Allow students to react to each other’s responses.

- After posing a question and before calling on a respondent, wait a few seconds so all the students can formulate a response and have space and time to think.

- Do not require students to raise their hands before speaking if the class is small.

- Never belittle student questions or responses.

- Do not get sidetracked by individual students: students can be invited to stay after class or stop by during office hours if they wish for further discussion on a topic.

- Do not lapse into lecture; this is one of the single greatest obstacles to student participation.

- When you have a large class, it is best to separate students into small groups: after the students have considered the questions in small groups, it is easier to obtain full participation during a whole-class discussion.

The use of discussion requires that you develop good communication skills. It also requires that you sense the mood and climate of the class. To be effective, discussion should be used for an intended purpose, not simply because it provides a voice for the students. The use of discussion should also be weighed against certain constraints such as time, number of objectives to attain, and physical space. It can be very effective for fostering application and exercising critical thinking and communication skills.

Discussion Exercises

There are a number of ways you can ignite discussion in the classroom.

| Think-Pair-Share |

|

| Buzz Groups |

|

| Socratic Method |

|

| “Jump Start” Vehicle |

|

Try to keep a record of what has been said on the whiteboard or on flipchart paper. You may find that this engages more students as they can see the connections being made while discussing them.

It also allows you to go back to the discussion points and establish if you have covered all that was needed in the seminar.

Methods for Facilitating Discussion

Following are some methods for facilitating discussions:

Case Studies

Method: the facilitator selects a case study that is suitable for the class and presents it to the class. The presentation is followed by discussion of the case study.

TRY THIS: record the crucial details for reference during the discussion, this will provide the students with a visual reference during class and they can photograph it for their notes later.**

Philips 66

Method: first define the topic of discussion with the class. Select six people and allow them six minutes for discussion. The class actively listens to the discussion and prepares to engage in a larger discussion afterwards. You may wish to designate a student or a few students to record the main points given by the initial six people for reference during the larger discussion.

TRY THIS: put the student’s names in a hat so that the students are selected entirely at random.

Committee Work & Reports

Method: Students work in small groups developing interpersonal and organizational skills, completing an assigned task. The groups are provided with a specific task as well as the needed information and resources to complete that task. The groups are given a set period of time to complete the task which is then presented to the whole class. Follow this up with discussion!

Best Practice: make sure that the material for the class is easily able to be broken up into small components that can be handled by different groups. Interpersonal conflicts can arise when personalities clash or if some members find themselves doing most of the work; be ready to jump in to keep the groups motivated.

Experience Discussions

Method: following the presentation or report on the main point of a book/article/life experience students engage in a discussion on pertinent issues and points of view as experienced. This method relies on the experience of the students within the class, some students may require more time to consider the experience and craft a response. Some participants may experience trouble relating to one another.

Asking the Right Kinds of Questions

Asking the right kinds of questions is important. Wilen and Clegg (1994) took five research reviews and identified teaching practices that were positively correlated with student achievement.

The most effective teachers:

- clearly phrase their questions and ask primarily academic questions rather than questions that are procedural, affective or personal

- ask only one question at a time

- attempt to ask questions at both a high and low cognitive level

- try to balance volunteered and non-volunteered responses which keeps students alert but gives them the opportunity to answer

- encourage students to clarify or support their responses which stimulates further thinking

- acknowledges correct responses with praise; for praise to be effective, it must be genuine, used sparingly, and should be specific

Effective teachers want students to respond to every question in some way, and the object is not to get the “right” answer.

Developing questions to spark and enhance discussion is difficult work. Questioning is an important skill for teaching assistants and is a skill that will take practice to develop.

When developing questions ahead of facilitating a discussion think about whether your questions are closed (having limited or yes/no responses) or open (requiring more critical thought and responses). For more information on the types of questions you can ask see the matrix on the following page.

REMEMBER

Your questions might not always get a response right away. It is important to allow students some time to think about the question before responding. Allow your students 5 to 10 seconds to think about the question before rephrasing your question.

When engaging students in discussions, there are 3 techniques that will help you facilitate meaningful, vigorous discussion:

- Reinforcing participation: reinforce student participation in a positive way to encourage future participation – this can be done in both verbal and non-verbal ways.

- Readjusting/Focusing: sometimes student responses may appear unconnected to the class content – try and make connections, encourage students to state the connection they are seeing to provide clarity for their response.

- Probing: student responses may be superficial, encourage more complex thinking and response by probing student responses for more.

(Centre for Teaching and Learning – Illinois University, 2019)

Examples of Probing Questions

(from Effective Teaching in Higher Education by Brown & Atkins, p.73)

- Does that always apply?

- How is that relevant?

- Can you give me an example?

- Is there an alternative viewpoint?

- How reliable is the evidence?

- How accurate is your description?

- You say it is x, which particular kind of x?

- What is the underlying principle then?