2 It Begins in Community

Sabreina Dahab

It Begins in Community By Sabreina Dahab

Throughout this chapter, I hope to share with you a glimpse of my journey and how it’s been shaped by a transition from Black liberalism to Black radicalism, by grassroots activism, by the complexities of being elected within colonial systems and by the foundational lesson I’ve learned from my parents and my community, my first site of education.

If there’s anything I hope you carry with you from this chapter, it’s these two things: if you choose to formally enter these systems, remember that we are not here to be comfortable, we are here to reduce the harm that colonial systems impart on Black and racialized students. And in a world where so many of us are carrying unimaginable grief and hardship, our starting point must always be kindness and gentleness.

Police-Free Schools Hamilton

On June 22nd, 2020, I co-led hundreds of Black and racialized youth across the Hamilton Wentworth District School Board (HWDSB) in a historic 6 hour sit-in demanding the termination of the School Resource Officer Program (SRO). This program, a partnership between the Hamilton police and the HWDSB, placed armed officers in both elementary and high schools. This program included armed officers delivering presentations on “human trafficking, internet safety, bullying, vaping and cyber-bullying,”, but their presence has raised concerns around safety for students (Mitchell 2020). The sit-in was a culmination of a month-long campaign where we had documented students’ experiences of police interactions in schools that made students feel unsafe. We heard first hand accounts of carding, racial profiling, and other discriminatory interactions with officers (Mehdi, 2020). The root of the issue for many was that police in schools did not make students feel safe. Ultimately, our call was a demand for safety, dignity and learning environments that were free from surveillance and harm. More than that, our demand was for emancipatory pedagogies and spaces where we could critically think about the world we live in and how to make it better and for us and many other Black and Racialized students, that didn’t involve police with guns patrolling our hallways.

After six hours of shutting down Main Street right across from Hamilton City Hall, we all cheered as the HWDSB trustees voted to terminate their partnership with the Hamilton Police (Mitchell, 2020). For once, we began to feel a semblance of justice for ourselves, for our peers and for all the students who came and will come after us.

Similar school boards across the province have had similar wins including the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), Peel District School Board (PDSB) and the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board (OCDSB) (Samuels-Wortley, 2021). Police in school programs first emerged in the United States in the 1950s and re-gained popularity in Canada and across the United States in the 1990s (Samuels-Wortley, 2021). While government officials and policing institutions suggest that police in schools programs exist to create safer schools, research on the benefits of police in schools programs is either very limited, or contradicts the suggestion that police create safer schools (Samuels-Wortley, 2021).

Four years later, our victory is under threat. I am writing this chapter about halfway through the 2025 year where education minister Paul Calandra has tabled Bill 33, legislation that would mandate police back into schools (Ontario Newsroom, 2025). The Elementary Teachers Federation of Ontario has rightfully opposed the legislative proposal, saying that “by turning school boards into scapegoats and bringing back police in schools without consultation, the Ford government is attacking both equity and democracy in one misguided stroke. It also places the decision-making power in the hands of police and government, completely eroding the power and voice of the community” (2025). The Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) has also outlined concerns and its position on the SRO program in a recent report called Dreams Delayed. The OHRC, in their report articulate that:

“Police presence and surveillance inside schools has a disproportionate impact on Indigenous, Black and other Racialized students. Historically, police have been part of a broader system of racism and discrimination across multiple levels, including child welfare and justice. Police in schools may subject Black and other Racialized children, and particularly Black boys, to a higher level of surveillance that could ultimately significantly impact their mental health and education” (2025)

The Elementary Teachers Federation of Ontario (ETFO) rightfully suggests that the most recent legislative announcements from the minister of education are an attempt to scapegoat local boards after they announced a provincial budget that does not meaningfully address the funding shortages in public education. Bill 33 also makes it easier for the province to take over schools. The legislation is an attack on local democracy and public education. The conservatives continue to scapegoat real issues in education as simply “board mismanagement”, and ignore the decades of cuts to education by the very same government. ETFO has built a tool at buildingbetterschools.ca that breaks down just how shortchanged each school is.

Policing in schools tells a story about the pervasive role of the carceral arm of the state in the education sector (Maynard, 2017). The criminal legal system interacts with the education sector by creating classrooms that mimic structures of prisons and prison guards. (Maynard, 2017). Think about it for a moment. You are in a place to learn, play with your friends and learn important life lessons. You leave your classroom to grab something from your locker and you see two police officers patrolling the hallways. Or, imagine walking into a classroom and instead of seeing your teacher at the front, you see a police officer, in full uniform teaching today’s lesson. How does this make you feel? How does a police officer with a gun roaming your hallways change your learning experience? How does it impact your day to day as a student who is Black or Racialized? How does it impact your sense of safety?

When I think about the education system, I think about its liberatory potential. What I mean by this is I think about how education can be a powerful tool to equip students and youth with the skills to think critically about the world we live in and how to make it better and more just. This is a vision that does not include cops, but does include an education system that is well funded, where students have access to caring adults and the support systems they need, not just academically but socially and emotionally. This includes investing in food programs, mental health supports, supports for disabled students, culturally relevant pedagogies, green spaces for youth and more. This might seem idealistic but if we can dream it up, we can achieve it. We just need visionary leaders with the foresight to build an education system that truly invests in students.

Where do I know from:

I was born in Canada to Muslim Egyptian immigrants whose journey, like that of many others, was rooted in the hope of building a better future for themselves and their children. My parents travelled throughout the United States and Canada looking for a place to settle before finally choosing to call Hamilton their home. They were escaping poverty, dictatorship and a life that didn’t feel fit to raise a family in.

My father is trained in the culinary arts and decided to open a restaurant shortly after settling in Hamilton. It was one of the first halal restaurants in the city serving food that met the dietary needs of the Muslim community. My mom spent her days helping him at the restaurant and her evenings making sure my siblings and I kept up with all our school work and extra curricular activities. I remember spending much of my childhood tucked away at the back of the restaurant, napping in storage rooms, doing my homework or getting to know those from the local community. The restaurant and how I knew it replaced my home. For 22 years, my parents ran the restaurant not just as a way to make ends meet, but also as a place of gathering for Muslims and Arabs across Hamilton. Every Ramadan, my parents would host Egyptian international students for meals at the restaurant so that they wouldn’t break fast alone. My dad regularly worked with newcomers, refugees, and international students supporting them with system navigation. As a result, very early on, I was exposed to the complex experiences of others whose journeys were shaped by the same hopes and struggles of my parents.

For many, food has always been a way to bring people together. Watching my parents care for and support newcomers and immigrants as a child had profound impacts on my understanding of community and responsibility. In learning about the experiences of many who came to share a meal, I was also learning about colonialism, incarceration, poverty, war, the painful realities of immigration trauma and how all of these experiences shaped our and their lives in both quiet and violent ways. It taught me about the resilience of our communities trying their best to survive systems that were never built for us. It taught me about sacrifice and the ways my parents and others in the community did all they could to protect and care for each other in lands that felt foreign. It taught me about what it means to radically show up for your community. It taught me about what it means to navigate systems alongside community members trying to survive. I remember sitting beside my dad helping him write character references for community members or former employees who were facing deportations, wondering if one more sentence, or one more platitude would help save a community member from deportation. I remember questioning the concept of a character reference – were not all people deserving of safety and a place to call home? I remember watching my dad navigate the legal system supporting many in our community who were criminalized. At that time, all I could think about was what it would look like if we didn’t have prisons separating families, but had real support for those who needed it most.

Growing up around a lot of Muslims and particularly visible Muslim women made me acutely aware of the realities of Islamophobia but there was still a disconnect in how I understood its immediate effects on my life. What I mean by this is I always understood Islamophobia as a distant reality – to me it was the media’s portrayal of Muslims as “terrorists” or the tired debates about whether or not the hijab was inherently oppressive. I saw Islamophobia as a problem that existed somewhere far away, something I could only address by educating those around me. I believed that if I could just teach people and make them see us as human, that things would change. As I began to understand how Islamophobia and white supremacy shaped immigration structures, policing and education, I began to understand how it was much larger and much more sinister.

Many immigrants internalize this belief. It’s a survival mechanism in a system and country that will never fully feel like home. These beliefs force our communities to stay docile and feel indebted to the nation that let us in. But the only thing we were ever doing was being silent towards a global system largely responsible for the very violence that many of us were fleeing.

Much of my understanding about how I moved through this world changed when I started wearing the hijab the summer before highschool. For those who may not know, the hijab is a scarf that covers your head that many muslim women wear. The hijab became a visible marker of my Muslim identity. In a post-9/11 era, a particular reality for me was being the target of patronizing ‘savior’ narratives, unsolicited comments or interventions under the guise of liberation or concern. I knew that these remarks carried with them judgement and the assumption that I was in need of some sort of saving and was forced to wear the hijab. That I was now in a “civilized” country and no longer needed to cover my hair and my body. The next few years, as my experience treading on these lands began to shift, I started thinking critically about the world I lived in. This shaped my desire to begin dispelling myths about Islam and Muslims. When I was in grade 11 and 12, I was the co-president of the Muslim Students Association at my high school, in Hamilton.

As a member of the Muslim Student Association at my high school, I wanted to address some of these misconceptions with my classmates and peers. To do this, we decided to organize an Islam Awareness Week. We invited guest speakers, hosted a diversity fair and built a world map to show how diverse our school was. It was something we felt very proud of. Very quickly, I became alive to the reality that Islamophobia was not a distant issue that I just needed to educate people on, but was a reality that was impacting us in our very own school. This began with students pulling down our posters, Muslim students being told they were terrorists, or our struggle to find a place for Friday prayer. Our experiences were not just coming from other students, but teachers spreading harmful narratives about Muslims all riddled in orientalism and racism. In response to our experiences at school, and at the time, and only a few short weeks after the Quebec mosque shooting, where a gunman entered the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec City and killed 6 worshippers, we organized a ring of peace to promote diversity and unity in our school.

Orientalism, a concept popularized by scholar Edward Said in his book, refers to the way the Western World has historically represented and constructed the “East”. Particularly the Middle East, Asia, and North Africa were portrayed as exotic, backwards, uncivilized and inherently inferior (Said, 1978). Orientalism is a look at the world through a colonial and white supremacist lens that justifies western hegemony (Said, 1978). Said, in his book, suggests that orientalism is not just found in literature or art but is a portrayal that informs policy, media, academia and how the West more broadly understands and engages with non-Western societies (1978). Think of movies like Aladdin and their portrayal of the Middle East. The setting is in this exotic far away and dangerous place. People from the “Middle East” are portrayed as barbaric and cruel. Or think about the ongoing dehumanization of Palestinians. Media and political discourse often frames Palestinians not as people resisting occupation and apartheid, but as “terrorists” and “human shields”. Israel, globally is then positioned as the only democracy in the Middle East, and a civilized nation bringing order to a savage Middle East. You then can begin to understand how settler colonialism is justified. To better understand how orientalism impacted many of those my dad supports, we can look at the way Arabs and Muslims were stereotyped as terrorists or extremists and how this leads to immediate suspicion towards anyone perceived as arab or muslim. For many, this results in an everyday life that is shaped by constant surveillance and scrutiny.

Being deeply connected to the Muslim community growing up, reading Edward Said’s work and reflecting on my own high school experience, I began to fundamentally change how I understand Islamophobia and its dynamics and impact. I no longer believed that Islamophobia was limited to the media’s portrayal of Muslims. The media’s portrayal of Muslims was simply a tool that manufactured the consent of rampant Islamophobia locally and globally. It was no longer about educating others about some abstract issue, but it was a reality we were living through. Suddenly, it wasn’t just about educating others, it was about fighting for more – representation, justice, and safe spaces to be who we are and practice what we believe in. We spent the next few months, through the Muslim Student Association meeting with the administration and senior staff at the school board thinking about what Muslim students across our board needed and were experiencing. We talked about the lack of access to prayer spaces, the overt and covert Islamophobic comments made to Muslim students by teachers and peers and the weaponization of suspensions and expulsions against Arab boys.

In the introduction of this book, professor Damptey perfectly unpacks the tensions with race, its weaponization and how it’s constructed around the world. My dad is nubian, an Indigenous African ethnic group and my mom is ethnically Arab. Nubia is a region along the Nile River and historically spans from present day Aswan towards northern Sudan (Shinnie, 2013). Nubian people identify as descendants of an independent civilization with a distinct language, traditions and culture (Shinnie, 2013). During the British Colonial era in Egypt, there was an agreement in 1899 between Egypt and the British to arbitrarily establish a border, effectively dividing Nubia and its people between two modern nation-states: Egypt and Sudan (Saleh, 2023). Due to various development projects, rising water levels, and poverty, many Nubian people were forced to flee to northern regions in Egypt, including Cairo and other urban cities effectively displacing them (Saleh, 2023). My dad was born and raised in Alexandria, the second largest city in Egypt and along the Mediterranean coast. The history of Arabization in North Africa with the coming of Arabs meant that Arab identities themselves are often quite complicated and informed by erasure of Indigenous cultures. Many Nubians, including my dad, have identified as Arab by language and national identity but this is not the case for all Nubian people. Growing up, I didn’t know a lot about Nubian people, Nubia or Nubian culture. I internalized the idea that being Arab and Black were two distinct identities that couldn’t coexist. I realized that this couldn’t be the case because of how my dad was perceived. One time, I inquired about his experiences of Blackness in Canada and in Egypt. He shared that living in Egypt, he did not identify as Black. While this isn’t the case for many Nubian people or other Black communities in Egypt who do experience racialization and marginalization, my dad shared that he never had to think about his identity beyond being an Egyptian. In Canada, my dad is immediately read as a Black man. One of the functions of white supremacy is its denial of agency in self-identification. Speaking Arabic fluently and being immersed in Arab culture meant that our experiences of Blackness were different than that of many others, but in a white supremacists settler colonial context, proximity to Arab culture does not really protect him from anti-Blackness.

Over the years, I have learned a lot from the Black radical tradition. The powerful works of Malcolm X, the Black Panther Party, Cedric Robinson, Frantz Fanon and many others, have shaped much of the shift in my trajectory and thinking. One of the ways I like to think about this shift is through my own journey from Black liberalism to Black radicalism, which began when I started to see and understand the limits of reform. Working within institutions can bring about incremental change but it does not dismantle the underlying ideologies that inform these structures. Systems are led by people that can enter and exist as they please, but the ideologies underpinning these systems, including white supremacy, colonialism, and racism are deeply rooted in the foundation of these structures and it must be uprooted. There are many incredible thinkers and movements to learn from who challenge Black liberalism. I think about the Black Panther Party, Malcolm X, Assata Shaku, W.E.B Du Bois, Frantz Fanon amongst many others. Their work continues to serve as guides for movement leaders thinking about the world we live in and how to deconstruct it.

After graduating high school, I went on to complete my undergrad in political science, then my masters in labour studies at McMaster University. During this time, I co-founded a group called Hamilton Students for Justice. We were a grassroots coalition of students at the time, current and former students of the public education system trying to ameliorate the conditions of Black, Racialized and Disabled students. We hosted town halls, community meetings and protests advocating for structural change at the Hamilton Wentworth District School Board. Our work led to the termination of the police in schools program, the creation of a human rights office and the Human Rights and Equity Advisory Committee at the school board.

The 2022 Municipal Elections

Building on six years of advocacy for social justice and anti-racism, in 2022, I ran for trustee and became the first Black Muslim woman elected to the Hamilton Public School Board. Growing up I learned about the civil rights movements across North America, the history and ongoing impacts of residential schools and continued struggle against settler colonialism in Canada, watched the Arab Spring across the Middle East and North Africa, and anti-imperialist movements throughout the global south. These movements shaped a deep skepticism about whether or not systems built on oppression could truly be reformed from within. I had spent the better part of my late teenage years and early 20’s organizing outside of structures of power – whether that be on issues of police violence and the struggle to defund the police, the fight for affordable and dignified housing, or against racism and Islamophobia in the HWDSB. When I say organizing outside of structures of power, I am referring to organizing tactics including protests, public pressure campaigns and any other type of disruptive activism that happens from people not employed by or working with the institution we were challenging.

In our work, we were often met with institutional resistance. Whether we were demanding police free schools, stronger equity practices at the school board, or dignified and affordable housing from the city. It felt like every gain we advocated for not only took a lot of fighting for, but would not have happened without some sort of public pressure. So prior to deciding to run for trustee, the consistent refusal of those in power to meaningfully engage with community demands only further entrenched my doubts about whether meaningful change could happen from the inside.

This skepticism eventually turned into enough optimism where I decided to put my name on the ballot to be the ward 2 HWDSB trustee. I am writing this reflection about two and a half years into my term, humbly recognizing that there is so much more for me to learn about emancipatory pedagogies and how to make public education better. There are many ways to be a trustee and show up for your community with integrity and this is my particular experience. I have tried to do this role with intention. My hope for this chapter is to articulate what the last few years have been like and share some of the lessons I’ve learned along the way.

During the provincial election, my friend and at the time trustee candidate Ahona and I co-hosted several art based community events to talk to students and families about their dream schools. The picture above is a banner that reads “What does your dream school look like” students wrote things like “transformative justice” “compassion” “cultures of respect, love, consent, joy, equity and unlearning” and drew pictures of butterfly gardens

What is a School Board Trustee

I often make this joke that the trustee role is actually explaining to people what trustees do, so let’s start there!

Every four years during municipal elections, residents vote not only for their mayor and city councillor, but also for a school board trustee. Each trustee represents a ward within a jurisdiction and plays a key role in settling policy direction and overall school board governance.

Trustees set policy direction that guides school board operations, including decisions about programs, strategic planning, health and safety and more. Trustees are not responsible for implementing policies, this is the responsibility of the director and superintendents. Trustees also oversee the board’s budget, ensuring it is balanced. Trustees are also responsible for hiring the director of education, who manages the day-to-day operations and policy implementations.

Trustees are accountable to the community and must ensure transparency. An especially important role is helping families navigate the school system. Trustees help parents and students navigate concerns, connecting them to their superintendents, equity departments or sharing relevant policies.

Trustees attend by-weekly board meetings to discuss, debate, and propose policies. Trustees can bring forward motions. We also get to attend events in the community and at schools which is one of my favorite parts of the role.

There are many different ways to engage with your trustee or the board of trustees in general.

- You can email or call your local school trustee.

- You can invite your trustee representative to a meeting or event at your school

- You can sign up to delegate at a trustee meeting. If there is an item on the agenda that you are interested in speaking to, you can sign up to speak to the board during their meeting. Each board has a different procedure on signing up to delegate, but you can reach out to your trustee for more information.

- If you would like to speak to the trustees but don’t want to delegate and publicly speak to the board, you can submit a written correspondence that will be on the public meeting.

Ok, now that we’ve outlined the role of the trustee, let’s talk a little bit about what it’s been like!

The School-To-Prison Pipeline

It’s important to begin by contextualizing the education sector within a colonial context. The education sector is often perceived as a neutral site of knowledge dissemination. This perception aims to render education in the West as an objective truth, rather than a construct that is shaped by external forces – including social, political and cultural forces that intend to create a very particular experience for children (Apple, 1978). Education is not only profoundly shaped by external forces, education is part and parcel of a necessary tool that the state relies on to facilitate white supremacy, capital production and settler colonialism (Baghsaw et al., 2022). This includes but is not limited to education policy, curriculum development, educational methods etc. The education sector is deeply embedded within the power dynamics that rely on privileging particular worldviews over others – this is defined as Eurocentric education systems. (Bagshaw et al., 2022). The curriculum, teaching methodologies, education policy and legislation are intertwined in a political way of maintaining a particular social order that creates a generation of workers who maintain, in varying capacities, capital accumulation (Apple, 1978). To maintain these structures, the state relies on various forms of policing and surveillance to entrench capital productions and ideals of settler colonialism (Sears 19).

After my successful campaign, I quickly became alive to how the school-to-prison pipeline manifests through policies that marginalize and alienate Black, Arab and immigrant students, a reality I was familiar with, but did not understand the gravity of it in my own school board. The school-to-prison pipeline is defined as “this growing pattern of tracking students out of educational institutions, primarily via “zero tolerance” policies, and directly and/or indirectly, into the juvenile and adult criminal justice system” (Heitzeg, 2009). The school-to-prison pipeline can be traced to the ways youth violence is sensationalized in the media and the expansion of the incarceration system. This pipeline is facilitated by many aspects of the education system, but predominantly through “zero-tolerance” legislation that has no measurable impact on school safety. However, zero-tolerance policies “are associated with a number of negative effects’ racially disproportionality, increased suspensions and expulsions, elevated drop-out rates, and multiple legal issues related to due process” (Heitzeg, 2009).

As a newly elected trustee, I began receiving frequent calls from Black, Arab, and newcomer families concerned about the disproportionate use of suspensions and expulsions against their children, highlighting the urgent need for disaggregated data. To address this policy gap, in April of 2023, I brought forward a motion requesting that staff collect and publicly release disaggregated data on suspensions and expulsions, a measure long demanded by the community (Hristova, 2023). Many large urban school boards had been collecting and releasing disaggregated suspension and expulsion data for many years and it was time for the HWDSB to join that list. The Toronto District School Board has been collecting desegregated suspension and expulsion data since 2008. Similarly to the context in the Hamilton Wentworth District School board, this data came as a result of growing concerns about racial disparities in disciplinary measures and how they were impacting Black, Indigenous and Racialized students. The primary goal of collecting and releasing this data is to identify patterns so that school boards can begin to develop more equitable practices.

In June of 2023, HWDSB staff released the suspension and expulsion data and it revealed precisely what the community has been saying for years, that school disciplinary measures were disproportionately impacting Black and racialized students. Some key findings in the data included that the HWDSB was suspending

- First Nations, Black and Arabic speaking students at a higher rate than the board averages

- Boys, bisexual students and students with certain disabilities at higher than the board averages

- And that between 2021-2022, there were 38 suspensions that were in violation of the ministry ban on suspension and expulsion for students in Kindergarten to grade three.

When looking at disproportionality data, it’s important to ask why these patterns exist. Disproportionalities such as higher rates of discipline or lower academic outcomes among specific groups of students are not the result of differences in student behavior, but rather reflect systemic biases and unequal treatment. These disparities are often rooted in social inequities, institutional racism and white supremacy within the education system. This is a well documented reality that extends beyond the HWDSB and affects marginalized students across Canada (Hristova, 2023; HWDSB, 2023; Leitner, 2023).

Since this data has been released, I have requested additional reviews of HWDSB disciplinary procedures through a human rights lens, and proposed additional interventions to address disproportionalities.

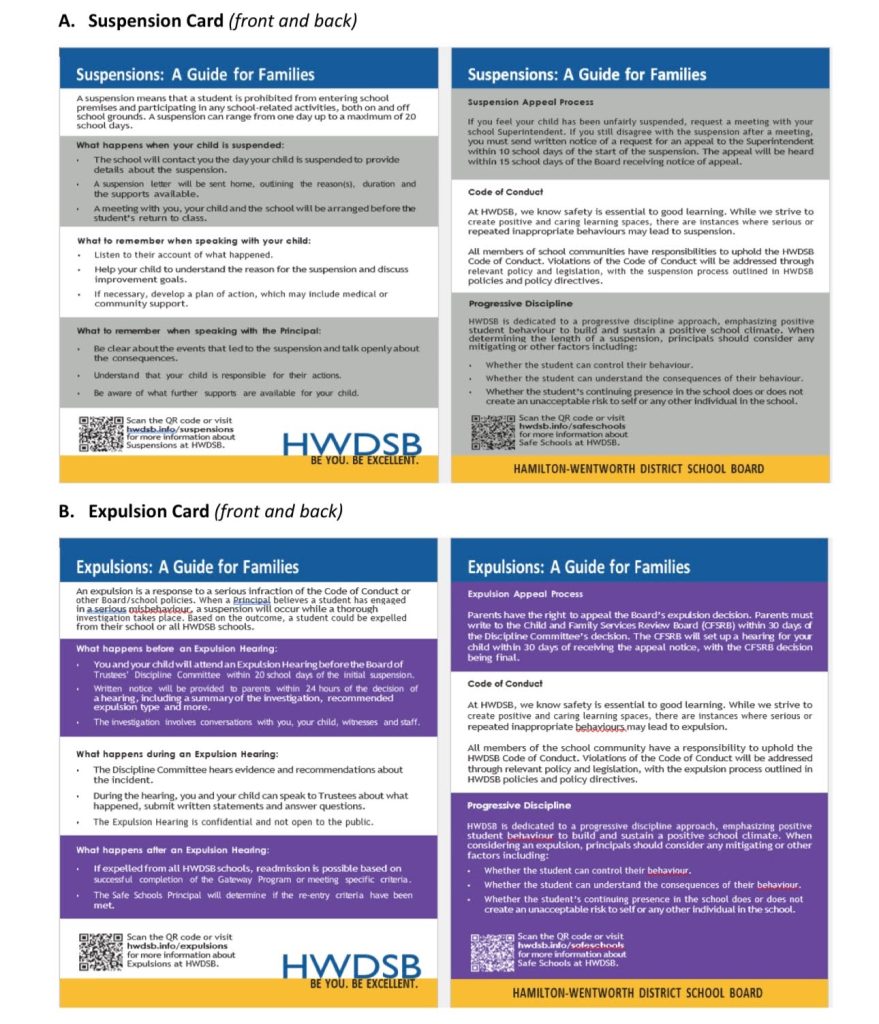

The most recent initiative in our work to address disproportionate use of suspensions and expulsions at the HWDSB is the development of suspension and expulsion information cards, introduced as a result of a motion I tabled to address concerns around due process and the lack of accessibility in our procedures for parents and guardians who do not speak English. These cards have been translated into the various languages spoken by families across our board and are intended to be used as an accessible guide that is sent home when a student is suspended or expelled. This helps ensure that parents who are not fluent in English understand the procedure, know their rights, and know what to expect while navigating a suspension or expulsion with their child. This is one of the ways I hope to ensure that parents are equipped with the tools they need to better advocate and support their children during this process.

This is an example of what the suspension and expulsion guides, translated into the top 10 languages spoken at our board will look like. Please note that this is a preliminary example as staff continue to make edits to the content. The plan is for these cards to be rolled out to schools in the fall of 2025 in various languages.

Censorship, Zionism, A Free Palestine and Ontario’s Education System

In October of 2023, many people became aware of the realities of the Israeli occupation and its brutal apartheid regime. Over the last year and a half, we’ve borne witness to a live streamed genocide in Gaza with non stop videos and images of the brutality of the violence Israel continues to inflict on the Palestinian people. According to the United Nations, since October of 2023, over 54,000 Palestinians have been killed with over 123,000 injured, 70% of all structures are destroyed or damaged and 50% of hospitals are partially functional (OHRC, 2025). The extent of the devastation and grief many people continue to feel can’t fully be captured, but it is one many students in Ontario’s education system have been holding since October of 2023. We’ve also had to grapple with the reality that any attempts to condemn the genocidal regime and call attention to the occupation of Gaza is met with defamatory charges of anti-semitism.

Muslim, Palestinian, Arab and allied students in our board began reaching out to share troubling experiences of anti-Palestinian racism, Islamophobia and censorship in their schools. In a report titled Anti-Palestinian Racism: Naming. Framing and Manifestation, the Arab-Canadian Lawyers Association has defined Anti-Palestinian as racism that denies Palestinian identity or history, the silencing of Palestinian voices and the discrimination faced by those expressing solidarity with Palestine (Majid, 2022). This includes denying the Nakba, justifying violence against Palestinian people and the denial and refusal to acknowledge Palestinians as an Indigenous people (Majid, 2022). Students wearing green hijabs were likened to terrorists, students were told they were not allowed to talk about Gaza and were threatened with disciplinary measures, fundraisers to support humanitarian efforts were denied and students were silenced in their classrooms. This only compounded the grief that many students were experiencing.

In December of 2023, after consultation with students in our system and alongside the student trustees at the time, I brought forward a motion requesting that all HWDSB staff receive training on Islamophobia, anti-Palestinian racism and anti-semitism. This motion also requested that HWDSB staff update our dress code guidelines to protect students from discrimination against cultural dress, including the kuffiyeh. While some of these changes might seem small when considering the ongoing censorship across educational institutional, explicitly naming the kuffiyeh as protected wear in official board policy, and engaging with all staff on anti-Palestinian racism affirms our ability to resist Zionism, and the ongoing erasure of Palestinian identity, culture and solidarity.

Since October of 2023, I have talked to students, educators and parents across Ontario about how they have experienced the education sector and issues related to Palestine. I’ve heard about the increased levels of Islamophobia and anti-Palestinian racism, ongoing censorship, and the repeated conflation of anti-semitism and anti-zionism. I’ve also heard from educators who want to engage in thoughtful conversations with their students but have either been threatened with disciplinary measures or are actively undergoing investigations. I often get asked how an education system could refuse to talk about an ongoing genocide. I remind students, parents and educators that as Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang claim in Decolonization is Not a Metaphor, education is deeply shaped by settler colonial logic. They write that this logic functions in two key ways: first, through the “invisibilized dynamics of settler colonialism [that] mark the organization, governance, curricula, and assessment of compulsory learning”; and second, through the dominance of settler perspectives, which are legitimized as knowledge and research and then used “to rationalize and maintain unfair social structures” (Tuck & Yang, 2012). This dynamic is not new. Egerton Ryerson, Ontario’s first Superintendent of Education, openly described the purpose of public education as a tool for assimilation, stating that its aim was to “eliminate Indians by assimilating them” (Hanson, 2021).

Given this historical and ongoing context of the education sector, it becomes difficult to view the current suppression of Palestinian solidarity within schools as an aberration. Rather, it reflects an education system functioning precisely as it was designed to by upholding settler colonial power structures and suppressing resistance to them.

As I witnessed the unfolding genocide in Gaza and listened to stories of students across our board, I felt a deep responsibility to also remain unwavering in my commitment to the struggle for a free and liberated Palestine. Like many others across the Western world who faced censorship, workplace dismissals, or other repercussions for expressing solidarity with Palestine, in November of 2023, the board of trustees launched an external investigation into my social media activity as it related to my posts about Palestine. The process for investigating alleged breaches of the trustee code of conduct are confidential, which limits the extent to which I can write transparently about it in this chapter. However, what I can share is that in April of 2024, after roughly six months of being under investigation, the board received an internal report formally announcing that it would no longer be pursuing the allegations further. The investigation was closed. This outcome felt significant for the hundred of students and staff members who had been speaking out against anti-Palestinain racism and the ongoing genocide. I knew the importance of challenging the suppression I faced, not just for myself, but because of the broader implications for educational spaces. For me, there continues to be no consequences greater than the continued occupation of Palestine and no role more urgent than resisting any and all systems attempting to silence us.

The advice I often give to students and families is to remain steadfast in their advocacy. Effective advocacy requires an understanding of how to navigate school board systems and the policies that govern it. This includes knowing who the leaders, superintendents and trustees are and when to engage each. Equally important is understanding and familiarizing yourselves with the existing safeguards and policies intended to protect students. Also, understanding how to reference and leverage existing school board policies and procedures. Ultimately, informed and strategic advocacy is essential to empowering students and families to bring the struggle for a free Palestine into their classrooms and hallways.

Conclusion

In this chapter, I wrote about my transition from Black liberalism to Black radicalism when unpacking Islamophobia and how it is connected to the school-to-prison pipeline, disciplinary measures in schools and the pervasive censorship many students face when attempting to discuss Palestine. These issues serve to highlight specific trends I have observed over the last two years and have sought to address through policy interventions and system navigation support. However, these issues represent only a portion of challenges confronting students and educators across the education sector. The education sector is experiencing a manufactured crisis. I use the word “manufactured” deliberately, as successive liberal and conservative governments have systemically underfunded the education sector, mirroring trends seen across many other public sectors, including healthcare. The chronic defunding and underfunding of the education sectors means that students are sitting in larger class sizes, there is insufficient support for students with disabilities, there is a lack of secure teaching jobs and more. Every single issue in education can be traced back to a lack of funding, and a neoliberal agenda. These conditions are creating a crisis that threatens to undermine the educational well-being and academic success of students across Ontario.

To end off this chapter, I want to share some of the most important lessons I’ve learned over the last decade of being in and with the community.

- My parents and my community were my first teachers. This is where I learned some of the most valuable life lessons and I am deeply grateful to those I crossed paths with at the restaurant.

- We live in an increasingly challenging world where many of us are carrying unimaginable grief and hardship. Our starting point must always be kindness and gentleness.

- Around the board table, I am often either the only one or one of two/ three trustees voting for or against something. It’s uncomfortable and that’s okay. I like to remind myself that we’re not here to always be comfortable, we’re here to reduce the harm that colonial systems impart on students.

- The starting point must be access to due process and justice. All students and families deserve access to due process when dealing with issues related to their academic success and overall well-being.

- Empowering families and students to understand how to navigate systems is extremely important. We are only as effective as our ability to navigate and interpret policy, process and procedure.

- I have found my community of people, my family, my chosen family and my friends who keep me grounded and accountable during the toughest moments. These are moments that require me to be courageous and resilient, especially when I feel afraid.

- Integrity and excellence are core values that shape how I approach everything I do.

- One of my good friends always reminds me that “retreat is not surrender”. It is necessary that we pause, reflect, catch our breath and tend to our physical, emotional and spiritual needs.

To the brilliant students navigating an increasingly challenging world, remember that you deserve safe and supportive classrooms. This is a place where your needs are respected and met. You have the right to learn and play, to grow and to build meaningful friendships all while dreaming up and fighting for a better world. Don’t ever forget that you have rights in your schools and you’re allowed to advocate for yourself. There’s a community beyond those four walls of your school that loves you deeply and is rooting for you.

To educators across the system working to untangle white supremacy and build classrooms that see every single child, bell hooks reminds us that “to educate as the practice of freedom is a way of teaching that anyone can learn. That learning process comes easiest to those of us who teach who also believe that there is an aspect of our vocation that is sacred; who believe that our work is not merely to share information but to share in the intellectual and spiritual growth of our students. To teach in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of our students is essential if we are to provide the necessary condition where learning can most deeply and intimately begin” (hooks, 1994). Thank you for all that you do to care for every child.

To my family, my chosen family and my friends, thanks for always having my back. I love you.

Lots of love and solidarity,

Sabreina Dahab, HWDSB Ward 2 Trustee

References

Apple, M. W. (2013). Knowledge, power, and education. Routledge.

Arab Canadian Lawyers Association. (2022, April). Anti‑Palestinian racism: Naming, framing and manifestations [PDF]. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/61db30d12e169a5c45950345/t/627dcf83fa17ad41ff217964/1652412292220/Anti-Palestinian+Racism-+Naming%2C+Framing+and+Manifestations.pdf

Bagshaw, E., Cherubini, L., & Dockstader, J. Truth in Education: From Eurocentrism to Decolonization.

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress. Routledge.

Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario. (2025, May 29). ETFO responds to Ford government’s egregious overreach, forced return of police in schools [Media release]. ETFO. https://www.etfo.ca/news-publications/media-releases/etfo-responds-to-ford-governments-egregious-overreach-forced-return-of-police-in-schools

Frostad, S. (2020, August 4). HWDSB terminates Hamilton police school liaison program. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/7094973/hwdsb-terminates-hamilton-police-school-liaison-program/

Government of Ontario. (2025, May 29). Ontario to introduce legislation to strengthen school board oversight [Press release]. https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1005972/ontario-to-introduce-legislation-to-strengthen-school-board-oversight

Hamilton‑Wentworth District School Board. (2020, June 23). HWDSB trustees vote to end police liaison program. https://www.hwdsb.on.ca/blog/hwdsb-trustees-vote-to-end-police-liaison-program/

Hanson, Andy. Class Action: How Ontario’s Elementary Teachers Became a Political Force. Between the Lines, 2021.

Heitzeg, N. A. (2009). Education or incarceration: Zero tolerance policies and the school to prison pipeline. In Forum on public policy online (Vol. 2009, No. 2). Oxford Round Table. 406 West Florida Avenue, Urbana, IL 61801.

Hristova, B. (2023, April 17). HWDSB’s anti‑Islamophobia strategy leads to suspension concerns. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/hamilton/hwdsb-anti-islamophobia-strategy-school-suspensions-1.6881150

Maynard, R. (2017). Policing Black lives: State violence in Canada from slavery to the present. Fernwood Publishing.

Medhi, A. 2020. Anonymous Testimonials Re: Termination of the Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board (HWDSB) Police Liaison Program, Ontario, Canada, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1qbsM4rDiZXxbQf5eEz9uX8T-FZ6sTZkt8hTTmyeKxbM/edit

Mitchell, D. (2020, June 24). Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board terminates Hamilton Police School Liaison Program – hamilton. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/7094973/hwdsb-terminates-hamilton-police-school-liaison-program/

Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2025, March 27). Dreams delayed: Addressing systemic anti-Black racism and discrimination in Ontario’s public education system [Action Plan]. https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/dreams-delayed-addressing-systemic-anti-black-racism-and-discrimination-ontarios-public-education

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

Sears, Alan. Retooling the mind factory: Education in a lean state. University of Toronto Press, 2003.

Samuels‑Wortley, C. (2021, May). School‑based liaison programs: An examination of impacts and human rights implications [PDF]. BC Human Rights Clinic. https://bchumanrights.ca/wp-content/uploads/Samuels-Wortley_May2021_School-liaison-programs.pdf

Saleh, Y. (2023). To Identify With a Memory: A Case Study on Nubian post-displacement ethnic identity in contemporary Egypt.

Shinnie, P. L. (2013). Ancient Nubia. Routledge.

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.25058/issn.2011-2742.n38.04

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs – Occupied Palestinian Territory. (2025, May 28). Reported impact snapshot, Gaza Strip (28 May 2025).

https://www.ochaopt.org/content/reported-impact-snapshot-gaza-strip-28-may-2025

Media Attributions

- We Will Win

- This is a picture of my dad outside of the restaurant in Westdale Village

- The Ring of peace February 2017

- Dreaming Safer Schools Poster by Sabreina Dahab and Ahona Mehdi

- What does your dream school look like Banner

- HWDSB suspension card