6.2 Invertebrate Groups

Sponges

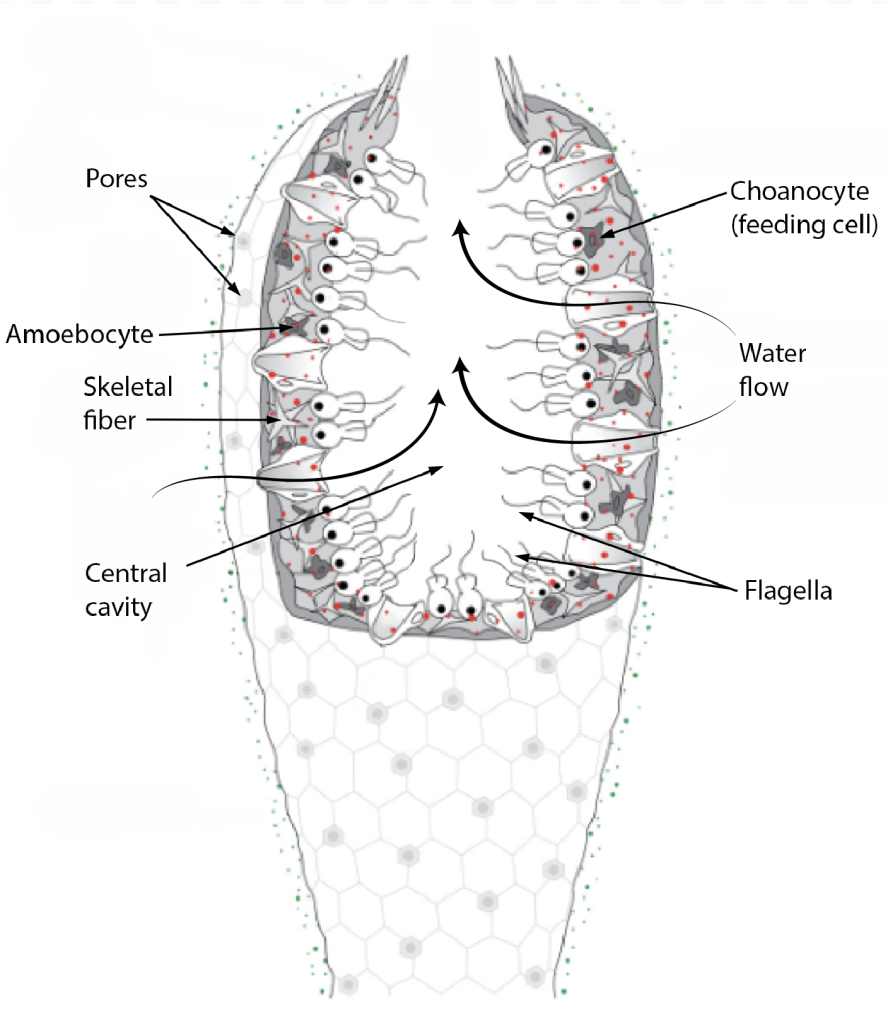

Sponges (phylum Porifera) are the simplest animals. They live in water, mostly in the ocean, and are usually attached to surfaces like rocks. Because they don’t move as adults, they can easily be mistaken for plants. However, sponges are animals that have been around for over 500 million years. Scientists believe that sponges probably evolved very early from colonial protists – single-celled organisms that lived together in groups.

Sponges don’t have true tissues, organs, or a nervous system. Instead, their bodies are made up of loosely organized cells. The sponge’s body is full of pores and channels. Water enters through the small openings, flows into a central cavity, and then exits through a larger opening at the top. Water constantly flows through their bodies, bringing in food and oxygen and carrying away waste. Sponges are filter feeders, meaning they feed by straining tiny food particles from the water as it flows through their bodies. This water movement is powered by special cells called choanocytes, which have flagella that beat to create a current. These cells also trap and engulf tiny food particles from the water. Amoebocytes then help digest food and carry it to other cells.

Sponges reproduce both sexually and asexually. Asexual reproduction is either by fragmentation (in which a piece of the sponge breaks off and develops into a new individual) or budding (an outgrowth from the parent that eventually detaches). Most sponges are hermaphroditic, meaning one individual can produce both eggs and sperm. Sperm is released, whereas the eggs are retained within the central cavity. Sperm carried by water currents fertilize the eggs of other sponges. Early larval development occurs within the sponge, and free-swimming larvae are then released. This is the only time that sponges exhibit mobility.

Cnidarians

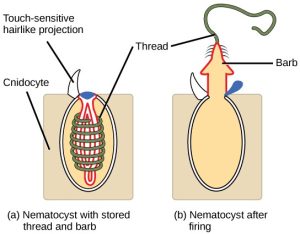

Cnidarians (phylum Cnidaria) are simple animals with true tissues, radial symmetry, and tentacles armed with stinging cells. This group includes sea anemones, corals, hydras, and jellies (often called jellyfish, though they are not actually fish). Most of the roughly 10,000 known cnidarian species live in the ocean.

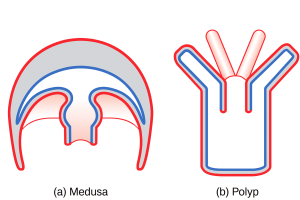

Cnidarians display two distinct body plans:

Polyp: Usually attached to a surface with its mouth facing upward (e.g. Hydra)

Medusa: Free-swimming and shaped like an umbrella with the mouth and tentacles hanging downward (e.g. jellies)

Some cnidarians live only as polyps, others only as medusae, and some alternate between both forms during their life cycle.

Cnidarians are carnivores. The tentacles are lined with special stinging cells called cnidocytes, which contain tiny, coiled threads that can shoot out and deliver toxins to stun or kill prey. They use their tentacles to capture prey and bring it into their digestive space, called the gastrovascular cavity. This space has only one opening that serves as both the mouth and anus (an incomplete digestive system). Food is taken into the gastrovascular cavity, enzymes are secreted into the cavity, and the cells lining the cavity absorb the nutrient products of the extracellular digestive process.

Flatworms

Flatworms (phylum Platyhelminthes) are among the simplest animals to exhibit bilateral symmetry. Flatworms have flattened, ribbon-like bodies and range in size from microscopic to several meters long. They lack specialized circulatory and respiratory systems, so gas exchange and nutrient distribution occur by diffusion, which limits their body thickness and contributes to their flat shape.

Most flatworms have a gastrovascular cavity with a single opening that serves as both mouth and anus. They also have a simple nervous system, which consists of two longitudinal nerve cords and a concentration of nerve cells (ganglia) at the head end. Some species have light-sensitive eyespots and chemical sensors that help them navigate their environment.

Most flatworms are hermaphroditic, possessing both male and female reproductive organs. Some species can also reproduce asexually through fragmentation and regeneration – a whole new worm can grow from just a small piece of the original!

Flatworms live in a variety of environments, including marine, freshwater, and moist terrestrial habitats. Some are free-living, while many others are parasitic. Free-living organisms live independently in their natural environments and obtain their own food. In contrast, parasitic organisms live inside or on a host organism and rely on the host for nutrients.

An example of a free-living flatworm is a planarian. The gastrovascular cavity of planarians is highly branched, increasing surface area for digestion and nutrient absorption. A muscular feeding tube extends from the mouth to suck in food.

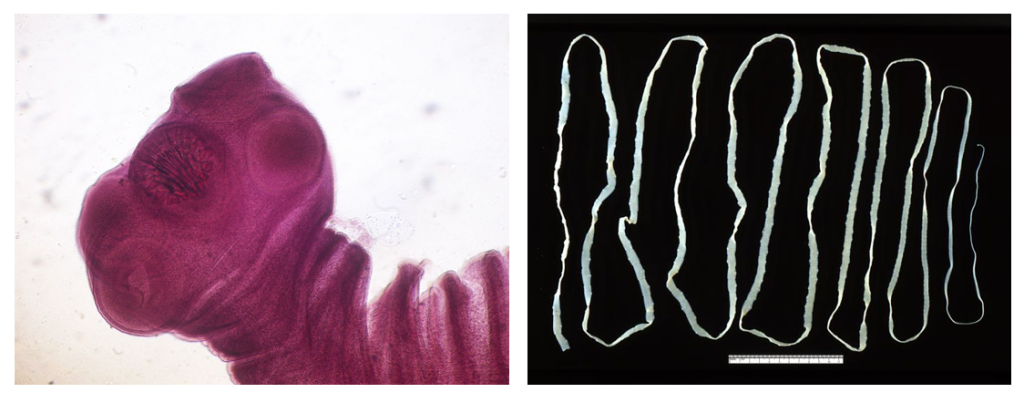

Tapeworms are parasitic flatworms that live in the intestines of vertebrates. They remain fixed using a specialized head that contains hooks and suckers. They have long, ribbon-like bodies made up of repeating units that can grow several meters long. Tapeworms do not have a digestive system; they absorb nutrients from the food matter passing them in the host’s intestine. Tapeworms have an interesting life cycle that often includes living in the muscle tissue of an intermediate host. When the muscle tissue is eaten by the primary host, the cycle is completed. There are several tapeworm parasites of humans that are acquired by eating uncooked or poorly cooked pork, beef, and fish.

Nematodes

Nematodes (phylum Nematoda), also known as roundworms, are slender, cylindrical worms that are tapered at each end. Nematodes are present in all habitats and are extremely common, although they are usually not visible. Their bodies are covered by a tough, flexible cuticle that they must shed to grow. They move with a whip-like motion using only longitudinal muscles.

Nematodes have a complete digestive system with a mouth and anus. While many are free-living decomposers, others are parasites of plants and animals, including humans. Parasitic species include pinworms and hookworms, and can be transmitted through contaminated food, soil, or water.

Arthropods

Arthropods (phylum Arthropoda) are the most diverse and numerous animals on Earth, accounting for about 85% of all known animal species, with many still undiscovered or undescribed. Arthropods have adapted to nearly every environment, from deep oceans to the skies.

Their name means “jointed legs,” which reflects one of their key features. These jointed appendages are highly specialized to serve a specific function, such as locomotion (walking, swimming, flying), feeding or defence. This specialization allows arthropods to adapt to a wide range of environments and lifestyles.

Arthropods have an exoskeleton, a rigid external covering that provides support, protection, and a surface for muscle attachment. It must be shed periodically for growth, in a process called moulting. Their body segments are often grouped into functional regions such as the head, thorax, and abdomen. They have a complete digestive system.

Arthropods are classified into four major subgroups:

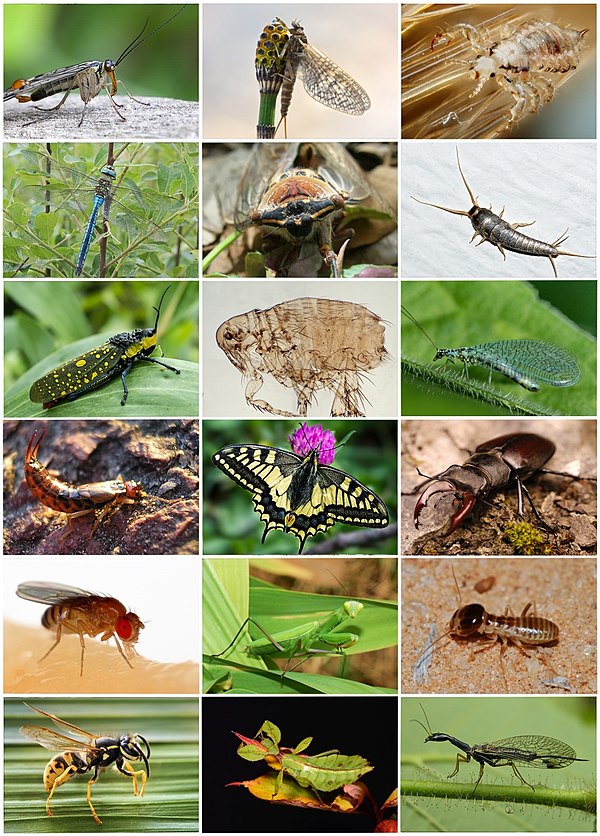

Insects

Figure 6.2.9 Left to right, top to bottom: “Common scorpionfly” by Richard Bartz, CC BY-SA 2.5, “March Brown Mayfly” by Richard Bartz, CC BY-SA 2.5, “Male Human Head Louse” by Gilles San Martin, CC BY-SA 2.0, “Blue Emporer” by Ocrdu, CC BY-SA 4.0, “Double Drummer” by Jan Anderson, CC BY-SA 2.0, “Silverfish” by Christian Fischer, CC BY-SA 3.0, “Aularches miliaris” by Crisco 1492, CC BY-SA 3.0, “Ctenocephalides-canis” by Luis Fernandez, CC BY-SA 2.5, “Chrysopidae” by Mathias Krumbholz, CC BY-SA 3.0, “F-auricularia” by Pudding4brains, Public Domain, “Old World Swallowtail (Papilio machaon)” by Uoaei1, CC BY-SA 4.0, “Lucanus cervus” by Simon A. Eugster, CC BY 3.0 Uported, “Drosophila melanogaster proboscis” by Sanjay Acharya, CC BY-SA 4.0, “Mantid religiosa” by Alvesgaspar, CC BY-SA 3.0 Unported, “Northern Harvester Termite (Hodotermes mossambicus)” by Bernard Dupont, CC BY-SA 2.0, “Vespula germanica” by Richard Bartz aka Makro Freak, CC BY-SA 2.5, “Phyllium Philippinicum” by Ebe.wiki, CC BY-SA 4.0, “Dichrostigma flavipes” by Beentree, CC BY-SA 3.0 Unported.

Insects are the largest group of arthropods and are found in nearly every terrestrial and freshwater habitat. They have a body divided into head, thorax, and abdomen, with three pairs of legs and usually one or two pairs of wings attached to the thorax. Insects breathe through tracheal tubes and have a well-developed nervous system. Common examples include ants, butterflies, beetles, and bees.

Many insects undergo metamorphosis, a developmental process that transforms them from immature forms into adults. The larval stage is often specialized for feeding and growth, while the adult is typically adapted for reproduction and dispersal. In complete metamorphosis, insects pass through distinct stages from egg, larva, pupa, and adult. A familiar example is the butterfly, which begins life as a caterpillar (larva), forms a chrysalis (pupa), and emerges as a winged adult.

In contrast, incomplete metamorphosis involves a gradual transformation from nymph to adult. Nymphs often resemble smaller, wingless versions of the adult and gradually develop adult features through successive moults. Insects such as mayflies, caddisflies, and stoneflies have aquatic nymphs that live in freshwater habitats and play important roles in the ecosystem. Because these nymphs are sensitive to pollution, they are widely used as bioindicators to assess the health of rivers, streams, and lakes.

Myriapods

Myriapods are terrestrial arthropods with long, segmented bodies and many legs. The most commonly found examples are centipedes and millipedes. Centipedes are fast-moving predators with one pair of legs per segment. Millipedes are slower detritivores with two pairs of legs per segment.

Crustaceans

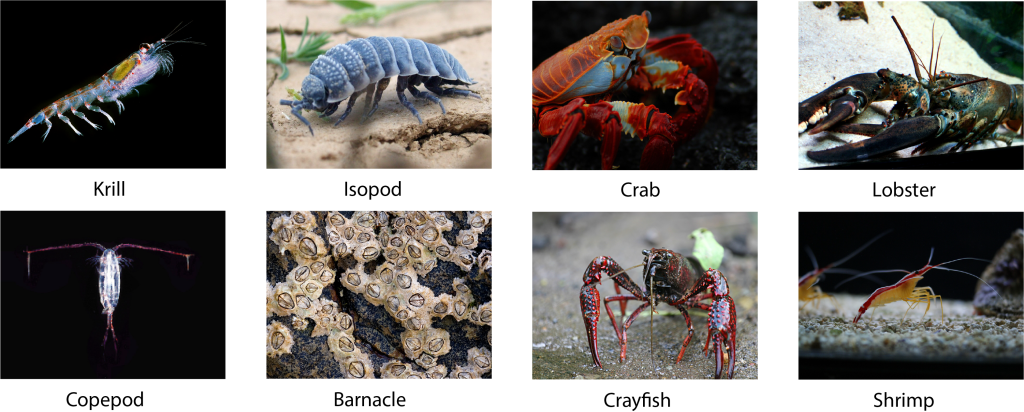

Crustaceans are primarily aquatic arthropods, including crabs, lobsters, shrimp, and barnacles. Some, like pill bugs or sow bugs, are adapted to life on land. Their bodies often have a cephalothorax (fused head and thorax) covered by a carapace. The exoskeleton of many species is also infused with calcium carbonate, which makes it even stronger than in other arthropods. Most crustaceans are carnivorous, but detritivores and filter feeders are also common.

Arachnids

Arachnids typically have eight legs, two body segments (cephalothorax and abdomen) and no antennae. Their first pair of appendages are often modified for feeding or injecting venom. This group includes spiders, scorpions, and ticks.

Mollusks

Mollusks (phylum Mollusca) are a diverse group of mostly marine animals, with over 85,000 described species and many more likely undiscovered. The name Mollusca means “soft-bodied,” and while many mollusks have hard shells, their soft internal anatomy is a defining feature. All mollusks share a basic body plan that includes a muscular foot (used for movement or attachment), a visceral mass (containing most internal organs), and a mantle (a tissue layer that may secrete a calcium carbonate shell). Many also have a radula, a tongue-like structure with rows of tiny teeth used for feeding. They have a complete digestive system with a mouth and an anus.

Mollusks are the second most diverse animal phylum. Although they are mostly marine, they can also be found in freshwater and terrestrial environments.

They are classified into several groups, but the three major groups are:

Bivalves

Bivalves are aquatic mollusks with bodies enclosed in a pair of hinged shells, or valves, joined at the dorsal (back) side. They lack a radula and instead feed by filtering food particles from water, which they draw in through a siphon. Bivalves include clams, oysters, mussels, and scallops.

Gastropods

Gastropods have a soft, asymmetrical body typically protected by a coiled shell, though some species lack a shell entirely. They can be found in marine, freshwater, and terrestrial environments. They move using a broad, muscular foot and feed with a radula that has a ribbon-like structure covered in tiny teeth. Many gastropods have a distinct head with tentacles and eyes. Gastropods include snails and slugs.

Cephalopods

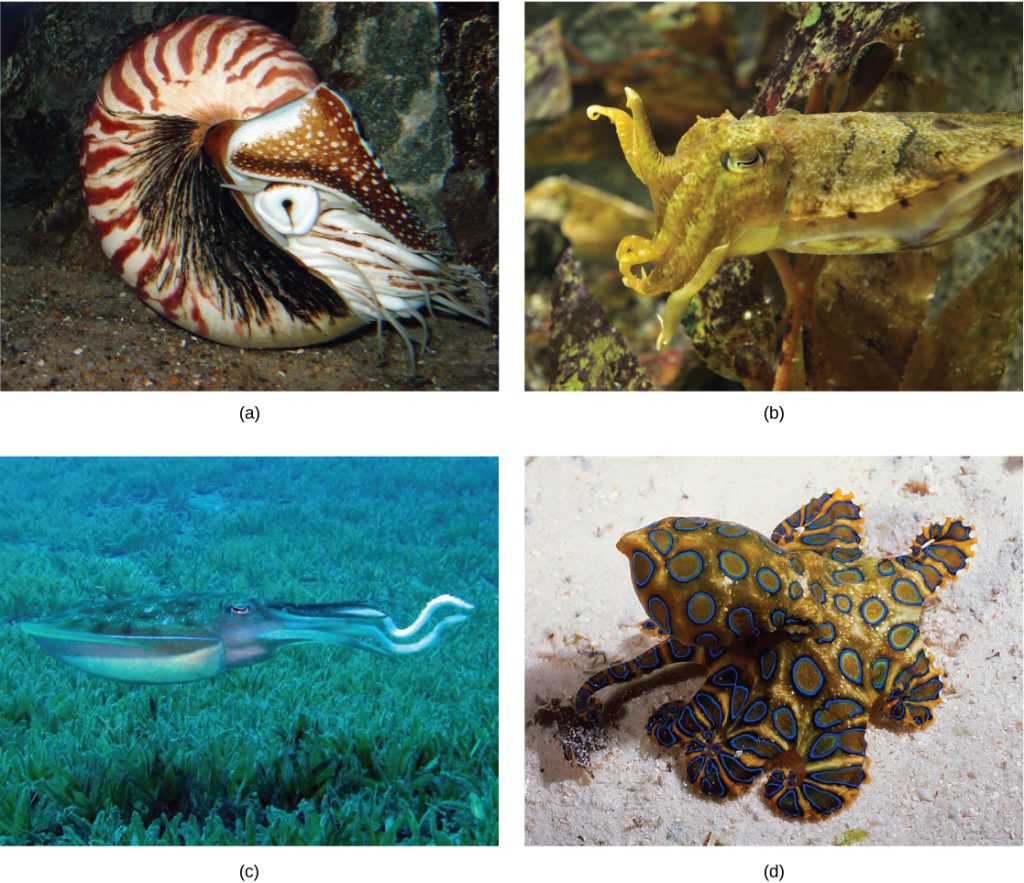

Cephalopods have a highly specialized body with a prominent head, large eyes, and a set of tentacles that surround the mouth. They are able to move quickly via jet propulsion by contracting the mantle cavity to forcefully eject a stream of water. They have a well-developed brain, which supports advanced behaviours such as problem-solving, learning, and communication. Some cephalopods are able to quickly change colour using pigment cells in their skin, which helps them camouflage or startle predators. Cephalopods include octopuses, squids, cuttlefish, and nautiluses.

Annelids

Annelids (phylum Annelida) are segmented worms found in marine, freshwater, and moist terrestrial environments. Their name comes from the Latin annellus, meaning “little ring,” referring to their ring-like body segments. This segmentation allows for flexibility and specialization of body regions. Annelids have a bilaterally symmetrical body structure, a complete digestive system, and a closed circulatory system. Many annelids have chaetae, bristle-like structures used for movement.

Earthworms

Earthworms are terrestrial or freshwater annelids with a smooth, segmented body and few chaetae per segment. They have a clitellum, a thickened ring that secretes mucus during reproduction and forms a cocoon for the eggs. Earthworms play an important role in soil health by aerating and enriching it.

Leeches

Leeches are mostly freshwater annelids with suckers at both ends of the body and no chaetae. Their body segmentation is often not reflected internally, allowing them to expand when feeding. Some leeches are blood-feeding parasites, while others are predators or scavengers.

Polychaetes

Polychaetes are mostly marine worms with many chaetae arranged on paired, fleshy appendages used in movement and gas exchange. They are often colourful and may live freely or in protective tubes.

Echinoderms

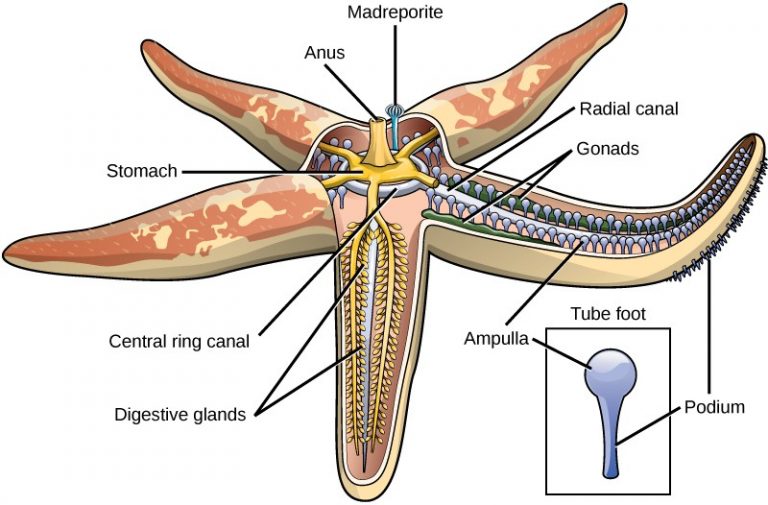

Echinoderms (phylum Echinodermata) are marine invertebrates known for their spiny skin and unique body structure. Adults exhibit radial symmetry, but their larvae are bilaterally symmetrical, reflecting their evolutionary ties to other bilaterally symmetrical animals. This phylum includes about 7,000 species, such as sea stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, brittle stars, and sea cucumbers.

Many echinoderms have remarkable regenerative abilities that make them capable of regrowing lost body parts, even from small fragments. They possess an endoskeleton (internal skeleton) made of small, hard plates of calcium carbonate, which provides support and protection.

Echinoderms have a water vascular system, a network of fluid-filled canals used for movement, gas exchange, and nutrient transport. They have tube feet, powered by hydraulic pressure, that extend through the body wall and allow for slow but powerful movements that are even strong enough to pry open the shells of bivalves.

Figure 6.2.23 Image Description

The image shows the internal anatomy of a starfish (sea star) with one arm cut open to reveal labelled structures. At the center is the stomach connected to a central ring canal, which branches into radial canals extending along each arm. Surrounding the canals are digestive glands and gonads. The madreporite is located on the aboral (upper) surface, near the center, with the anus nearby. Along the underside of the arm, the tube feet are shown, each connected to an ampulla. An inset highlights the tube foot structure, showing the ampulla and podium.

Chordates

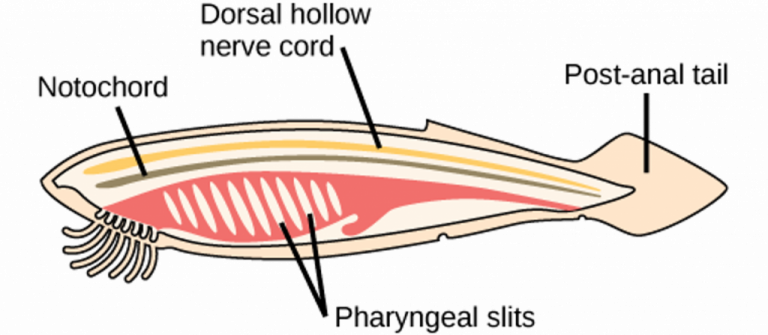

Chordates (phylum Chordata) are animals that share four key features at some point in their development:

- Notochord: The notochord is a flexible, rod-shaped structure that runs along the length of the body. It provides skeletal support and helps define the animal’s basic body plan. In invertebrate chordates, the notochord remains throughout life. In vertebrates, it is present during embryonic development and is later replaced by the vertebral column (spine).

- Dorsal Hollow Nerve Cord: This is a tube-like structure located above the notochord. It eventually forms the central nervous system—the brain and spinal cord. This is different from other invertebrates, which typically have solid nerve cords located on the ventral (belly) side.

- Pharyngeal Slits: These are openings in the pharynx (the region behind the mouth) that connect to the outside environment. In aquatic chordates, they function in filter feeding or develop into gills for breathing. In terrestrial vertebrates, they are modified into structures such as parts of the ear, tonsils, or jaw supports.

- Post-Anal Tail: This is a tail that extends beyond the anus. In many aquatic species, it helps with locomotion. In land animals, it may help with balance, communication, or courtship. In some species, like humans, the tail is present only during embryonic development and becomes vestigial in adults.

While most chordates are vertebrates (see more information in Chapter 7), there are two small groups of invertebrate chordates:

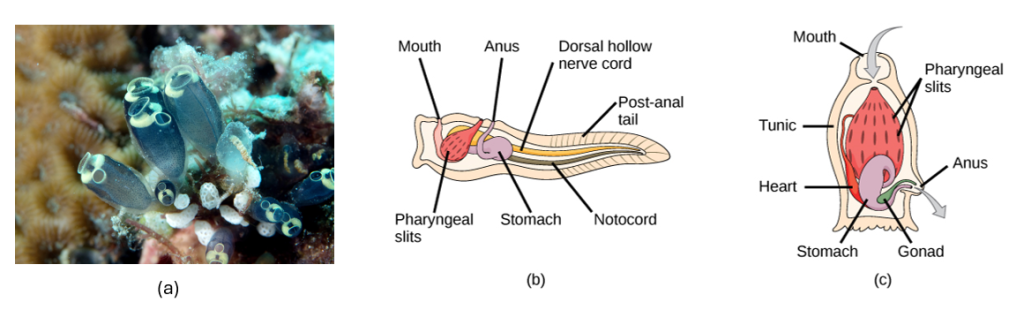

Tunicates

Tunicates, also called sea squirts, are marine animals that live in dark or shaded areas attached to rocks in shallow ocean waters. As adults, they have a sac-like body and filter food using pharyngeal slits. Although adult tunicates lack a notochord, nerve cord, and tail, their larvae have all four chordate features. A tunicate larva resembles a tiny tadpole, which swims for a few days then eventually attaches to a surface. It then undergoes metamorphosis to become the adult form, at which point the notochord, nerve cord, and tail disappear.

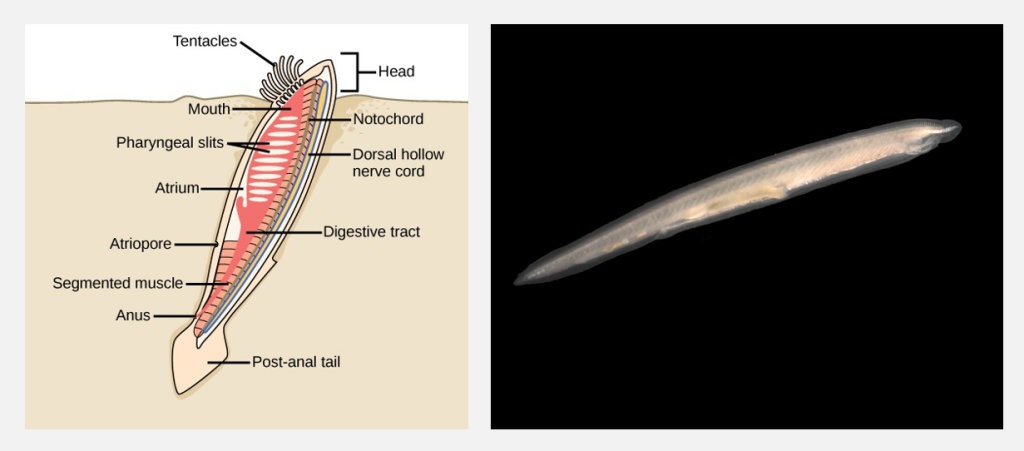

Lancelets

Lancelets are small, blade-like animals that grow to only a few centimetres in length. They are typically found buried in sand in warm, shallow marine waters. Unlike many other chordates, adult lancelets retain the four key features of chordates: a notochord, a dorsal hollow nerve cord, pharyngeal slits, and a post-anal tail. They swim using their tail and filter food from the water using their pharyngeal slits. Lancelets represent an ancient lineage, with fossils dating back to the middle of the Cambrian period over 500 million years ago. They are considered the closest living relatives of vertebrates, so they offer valuable insight into early chordate evolution.

Knowledge Check

Text Description

- They have a nervous system and true tissues

- They are free-swimming as adults

- They filter feed using choanocytes

- They reproduce only asexually

- Tentacles with cilia

- Radula

- Cnidocytes with stinging threads

- Gills with toxin glands

- They have a complete digestive system

- They are radially symmetrical

- They rely on diffusion for gas exchange

- They have segmented bodies

- They lack a circulatory system

- They have jointed appendages and an exoskeleton

- They have soft, unsegmented bodies

- They reproduce only through asexual budding

- Molluska

- Arthropoda

- Echinodermata

- Annelida

Answers:

- c. They filter feed using choanocytes

- c. Cnidocytes with stinging threads

- c. They rely on diffusion for gas exchange

- b. They have jointed appendages and an exoskeleton

- c. Echinodermata

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat

Prompt: Create 5 multiple-choice questions using the following content

“15.1 Features of the Animal Kingdom” from Biology and the Citizen by Colleen Jones is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Modifications: Edited and reworded