2.3 Speciation

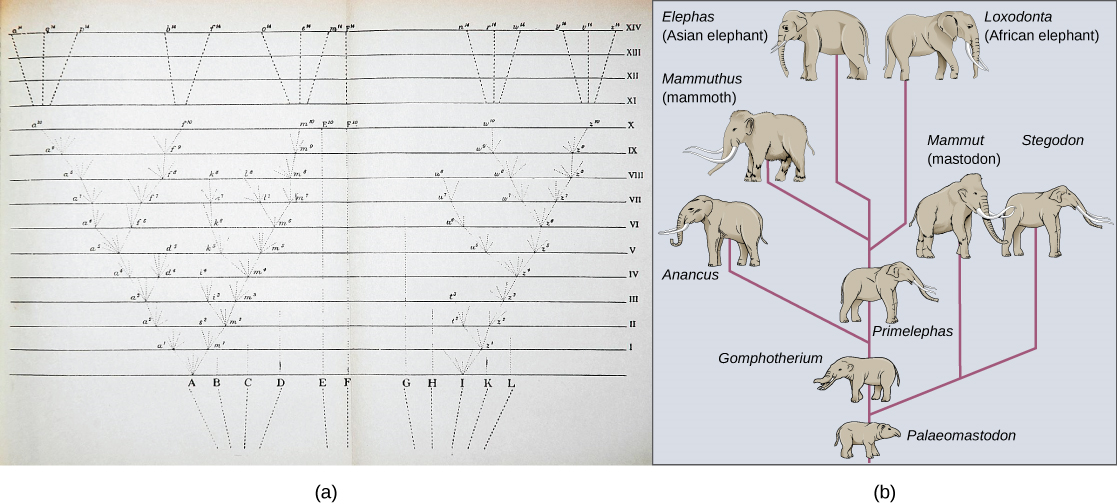

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. It occurs when genetic differences accumulate to the point that individuals from different populations can no longer interbreed and produce fertile offspring. Darwin envisioned this process as a branching event and diagrammed the process in On the Origin of Species (Figure 2.3.1a). Compare this illustration to the diagram of elephant evolution (Figure 2.3.1b), which shows that as one species changes over time, it branches to form more than one new species, repeatedly, as long as the population survives or until the organism becomes extinct.

Types of Speciation

For speciation to occur, two new populations must form from one original population, and they must evolve in such a way that it becomes impossible for individuals from the two new populations to interbreed. Biologists have proposed mechanisms by which this could occur that fall into two broad categories:

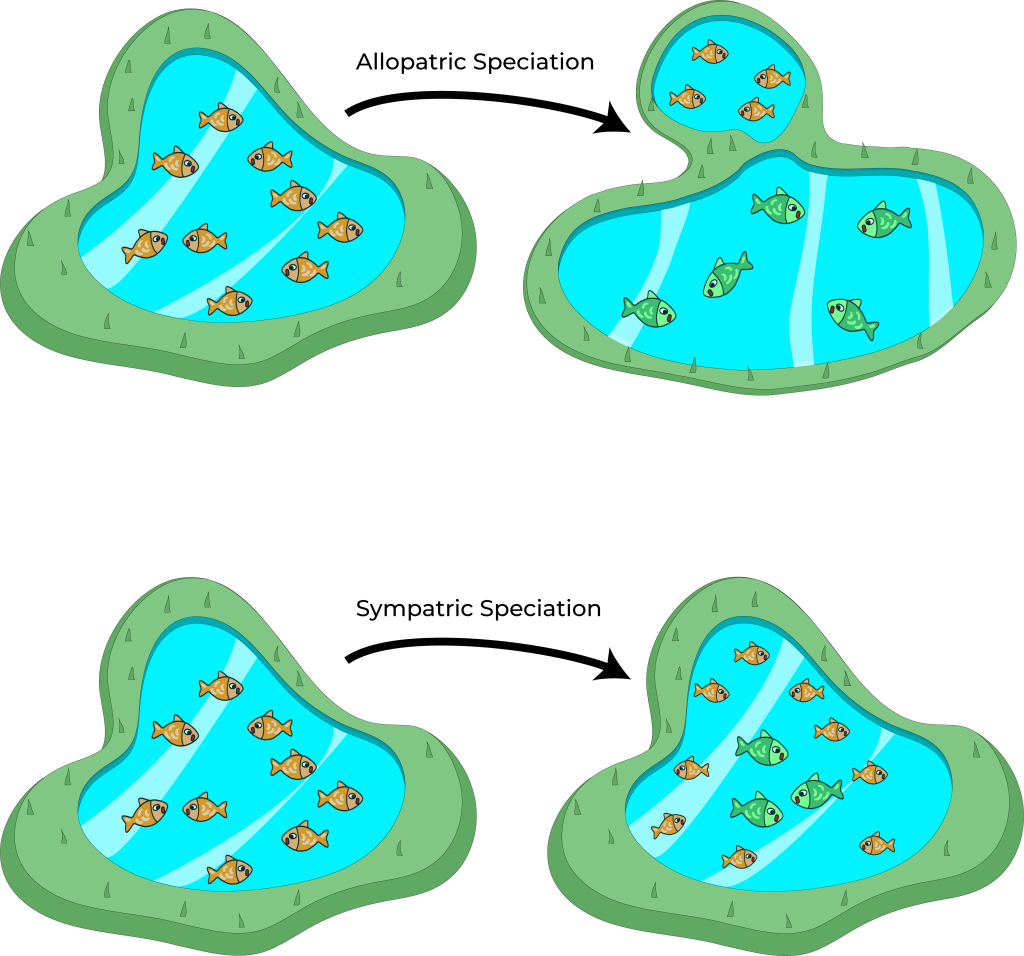

Figure 2.3.2 Image Description

The image shows two examples of speciation using fish in ponds.

Top illustration (Allopatric Speciation): A single pond with only orange fish splits into two separate ponds. In one pond, the orange fish remain, while in the other pond, the fish evolve into green fish, showing how physical separation leads to the formation of different species.

Bottom illustration (Sympatric Speciation): A single pond with only orange fish remains undivided. Over time, some fish evolve into green fish while coexisting in the same pond, showing how new species can form without physical separation.

This image contrasts allopatric speciation (species form due to geographic isolation) and sympatric speciation (species form in the same location).

Allopatric Speciation

Allopatric speciation occurs when a population is divided by a physical barrier, such as a mountain range, river, or large distance, which prevents individuals from different groups from interbreeding. Over time, these geographically isolated populations experience different environmental pressures, so they accumulate genetic differences that eventually lead to reproductive isolation. Even if the physical barrier is later removed, the populations may no longer be able to interbreed successfully, indicating that they have become distinct species.

Figure 2.3.3 Image Description

The graphic illustrates the process of allopatric speciation over time using a sequence of circles:

- The first circle, labelled Original Population, is entirely green, representing one unified population.

- Next, the circle is split in half by a vertical line labelled Geographic Barrier, showing the population divided into two isolated groups.

- In the third stage, labelled Reproductive Isolation, the two halves diverge, with one half remaining green and the other changing to blue, symbolizing genetic differences developing between the isolated groups.

- The final stage, Speciation, shows two separate, smaller circles—one green and one blue—indicating the formation of two distinct species.

- A large arrow labelled Time runs across the top, emphasizing that this process occurs gradually.

Figure 2.3.4 Image Description

The graphic shows two scenarios of how geographic isolation caused by climatic changes leads to speciation over time, illustrated with mountain ranges. A large arrow labelled Time runs across the top.

Isolation on Peaks (top row):

- The first image shows an original species population (in blue) spread across mountains.

- In the second image, labelled Isolation on Peaks, climatic changes restrict suitable habitat to higher elevations, isolating populations on mountaintops.

- In the third image, labelled Speciation, the isolated groups evolve separately, shown by one peak remaining blue while another turns green, representing the emergence of a new species.

Isolation in Valleys (bottom row):

- The first image shows the original species population (in blue) across mountain ranges and valleys.

- In the second image, labelled Isolation in Valleys, climatic changes confine suitable habitat to lower valleys, isolating populations there.

- In the final stage, labelled Speciation, populations diverge, shown by some areas remaining blue while others turn green, indicating the formation of a new species.

This diagram emphasizes how environmental changes and habitat fragmentation (on peaks or in valleys) can drive speciation.

A well-known case of allopatric speciation can be seen in the Galápagos finches that Charles Darwin observed. Today, there are around 15 distinct finch species across the Galápagos Islands, each with unique physical traits and beak shapes adapted to specific food sources like seeds, insects, and flowers. These birds are believed to have evolved from a single ancestral species that initially colonized the islands. As different groups settled on separate islands, they became geographically isolated. Over time, genetic variations emerged within each group. Traits that improved survival and reproduction in each unique environment became more common, eventually leading to the development of multiple new species.

Sympatric Speciation

Sympatric speciation occurs without any physical separation between populations. Instead, reproductive isolation arises within a shared habitat due to behavioural or ecological differences. For instance, individuals may begin to exploit different resources, develop distinct mating preferences, or undergo chromosomal changes that prevent successful reproduction with others in the population.

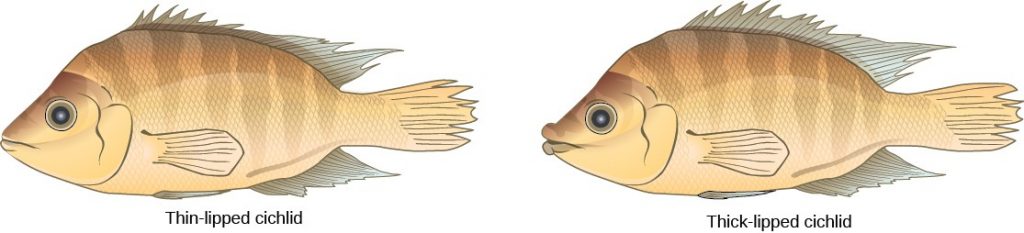

Figure 2.3.5 Image Description

Hidden text (could be the answer to the question posed above).

For example, imagine a species of fish that lived in a lake. As the population grew, competition for food also grew. Under pressure to find food, suppose that a group of these fish had the genetic flexibility to discover and feed off another resource that was unused by the other fish. What if this new food source were found at a different depth of the lake? Over time, those feeding on the second food source would interact more with each other than with the other fish; therefore, they would breed together as well. Offspring of these fish would likely behave as their parents and feed and live in the same area, keeping them separate from the original population. If this group of fish continued to remain separate from the first population, eventually sympatric speciation might occur as more genetic differences accumulated between them.

This scenario does play out in nature. For example, Lake Victoria in Africa is famous for its sympatric speciation of cichlid fish (Figure 11.19). In this locale, two types of cichlids live in the same geographic location, but they have come to have different morphologies that allow them to eat various food sources.

Overview

| Feature | Allopatric Speciation | Sympatric Speciation |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic Separation | Yes | No |

| Cause of Isolation | Physical barriers | Behavioural, ecological, or genetic factors |

| Common in | Animals and plants | More common in plants, some animals |

| Example | Squirrels separated by a canyon | Fish in the same lake choose different habitats |

Rate of Speciation

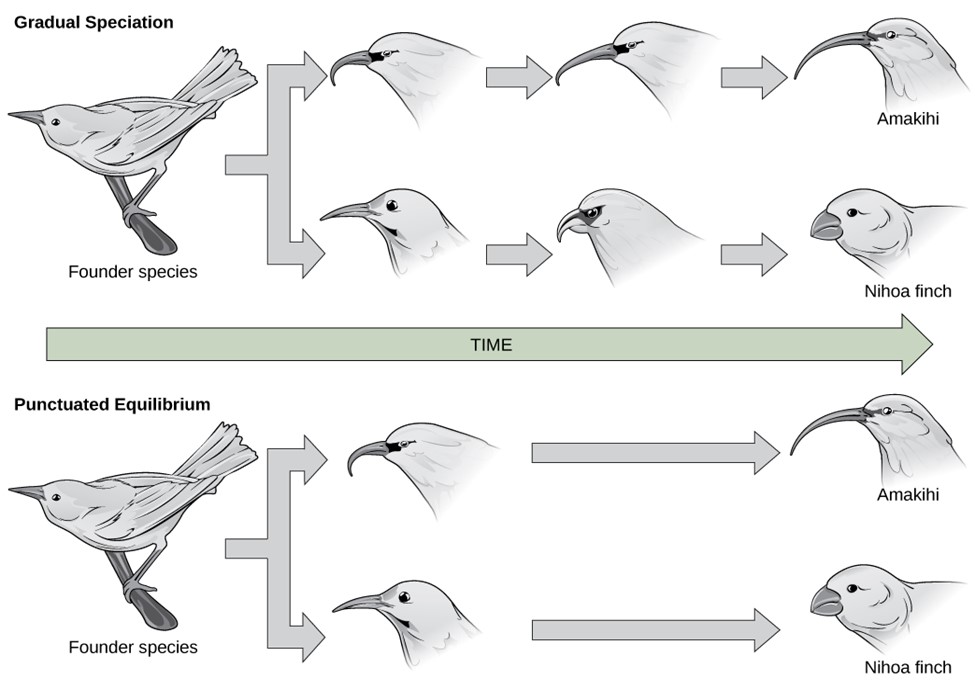

The rate of speciation can vary widely depending on environmental conditions, genetic factors, and ecological pressures. In some cases, species evolve gradually over millions of years through a slow accumulation of changes – a pattern known as gradualism. In contrast, other species may appear relatively suddenly in the fossil record, following long periods of little change. This pattern, called punctuated equilibrium, suggests that speciation can occur in rapid bursts, often triggered by environmental shifts or the colonization of new habitats.

Figure 2.3.7 Image Description

The diagram compares Gradual Speciation and Punctuated Equilibrium using bird evolution as an example.

- Top row (Gradual Speciation):

A founder species bird is shown on the left. Over time, it diverges gradually into different species, with intermediate forms depicted in a sequence of head illustrations. One lineage evolves into the Amakihi (shown with a long, curved beak), and another evolves into the Nihoa finch (shown with a short, thick beak). A long horizontal arrow labelled Time emphasizes that this process occurs slowly with many transitional forms. - Bottom row (Punctuated Equilibrium):

The same founder species bird is shown on the left. Instead of gradual change, there are long periods with little change, followed by rapid divergence. The intermediate forms are absent, and the founder species quickly gives rise to distinct species—the Amakihi and the Nihoa finch.

The illustration highlights the difference between gradualism, where species evolve slowly through continuous changes, and punctuated equilibrium, where species remain stable for long periods with sudden bursts of evolutionary change.

Knowledge Check

Text Description

- The accumulation of genetic differences between two populations

- The ability of populations to interbreed and produce fertile offspring

- The physical separation of populations

- The appearance of new traits within a population

- Speciation that occurs within a shared habitat due to behavioural differences

- Speciation that occurs when a physical barrier separates populations

- Speciation due to changes in chromosome numbers within a population

- Speciation that occurs when environmental pressures favour specific traits

- Two populations of squirrels being separated by a canyon

- Fish in the same lake developing distinct morphologies to exploit different food sources

- Finches on different islands developing different beak shapes

- A population of frogs being separated by a river

- Allopatric speciation occurs in the same geographic location, while sympatric speciation involves geographic separation

- Allopatric speciation requires physical barriers, while sympatric speciation occurs without physical barriers

- Allopatric speciation is more common in plants, while sympatric speciation is more common in animals

- Allopatric speciation results in hybrid inviability, while sympatric speciation leads to hybrid sterility

- Species evolve slowly over millions of years through gradual changes

- Speciation occurs in rapid bursts, often triggered by environmental shifts

- Speciation occurs as populations accumulate small genetic changes over time

- Species evolve at a constant rate over long periods of time

- Physical barriers like mountains or rivers

- Geographical separation of populations

- Behavioural, ecological, or genetic factors

- Changes in environmental conditions leading to natural disasters

Answers:

- a. The accumulation of genetic differences between two populations

- b. Speciation that occurs when a physical barrier separates populations

- b. Fish in the same lake developing distinct morphologies to exploit different food sources

- b. Allopatric speciation requires physical barriers, while sympatric speciation occurs without physical barriers

- b. Speciation occurs in rapid bursts, often triggered by environmental shifts

- c. Behavioural, ecological, or genetic factors

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat

Prompt: Create 6 multiple-choice questions using the following content

“Formation of New Species” from Principles of Biology by Lisa Bartee, Walter Shriner & Catherine Creech is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Modifications: Edited and reworded

“Speciation” from Introductory Biology: Ecology, Evolution, and Biodiversity by Erica Kosal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Modifications: Edited and reworded

“11.4 Speciation” from Biology and the Citizen by Colleen Jones is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Modifications: Edited and reworded