2.2 What is a Species?

This simple question is more difficult than it may appear. It turns out that scientists don’t always agree on the definition of a species. The different ideas about what constitutes a species are referred to as species concepts. There are around twenty-six different species concepts, but we will focus on the biological species concept. The biological species concept states that a species is a group of organisms that interbreed and produce fertile, viable offspring. According to this definition, one species is distinguished from another when, in nature, it is not possible for matings between individuals from each species to produce fertile offspring.

The biological species concept works well for scientists studying living creatures that have regular breeding patterns, such as insects, birds or mammals. However, this definition has limitations and is not always applicable (e.g. asexual organisms, fossils).

In some cases, the biological species concept is straightforward to apply. For instance, the western meadowlark (Sturnella neglecta) and the eastern meadowlark (Sturnella magna) (Figure 2.2.1) respectively inhabit the western and eastern halves of North America. Even though their breeding ranges overlap throughout many upper midwestern states, including Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, and Minnesota, the two groups do not interbreed. The courtship songs of the males of each species are distinctly different, and females of each species respond to the songs of the males of their species, leading to strong reproductive isolation between the two groups despite a high degree of similarity in appearance.

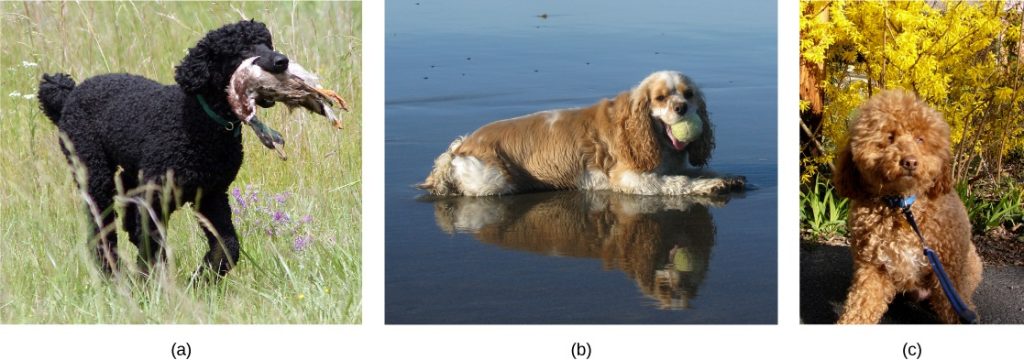

That being said, species’ appearance can be misleading in suggesting an ability or inability to mate. For example, even though domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) display phenotypic differences, such as size, build, and coat, most dogs can interbreed and produce viable puppies that can mature and sexually reproduce (Figure 2.2.2).

Reproductive Isolation

Reproductive barriers are any biological features or behaviours that prevent different species from interbreeding and producing fertile, viable offspring. These barriers are essential in maintaining species boundaries and are a key part of the Biological Species Concept.

Scientists organize them into two groups: prezygotic barriers and postzygotic barriers.

Prezygotic barriers

Recall that a zygote is a fertilized egg: the first cell of the development of an organism that reproduces sexually. Therefore, a prezygotic barrier is a mechanism that blocks reproduction from taking place; this includes barriers that prevent fertilization when organisms attempt reproduction.

Temporal Isolation

Many organisms only reproduce at certain times of the year, often just annually. Differences in breeding schedules, called temporal isolation, can act as a form of reproductive isolation. For example, two species of frogs inhabit the same area, but one reproduces from January to March, whereas the other reproduces from March to May (Figure 2.2.3).

Habitat Isolation

In some cases, populations of a species move or are moved to a new habitat and take up residence in a place that no longer overlaps with the other populations of the same species. This situation is called habitat isolation. Reproduction with the parent species ceases, and a new group exists that is now reproductively and genetically independent. For example, a cricket population that was divided after a flood could no longer interact with each other. Over time, the forces of natural selection, mutation, and genetic drift will likely result in the divergence of the two groups.

Behavioural Isolation

Behavioural isolation occurs when the presence or absence of a specific behaviour prevents reproduction from taking place. For example, male fireflies use specific light patterns to attract females. Various species of fireflies display their lights differently. If a male of one species tried to attract the female of another, she would not recognize the light pattern and would not mate with the male.

Mechanical Isolation

In some cases, closely related organisms attempt to mate, but their reproductive structures simply do not fit together. This is known as mechanical isolation, a type of reproductive barrier that prevents successful mating due to incompatible anatomical structures. For example, damselfly males of different species have differently shaped reproductive organs. If one species tries to mate with the female of another, their body parts simply do not align properly, preventing fertilization (Figure 2.2.4).

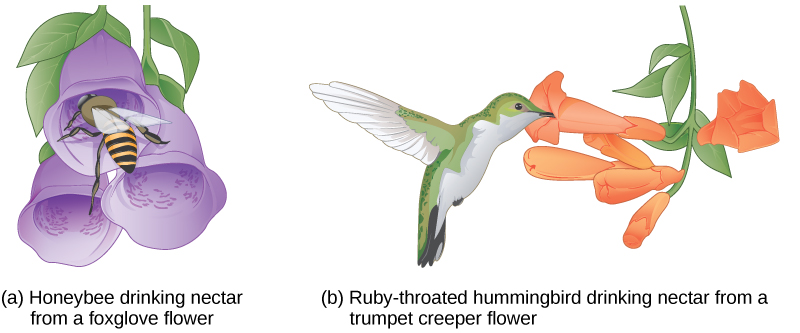

In plants, certain structures are aimed at attracting one type of pollinator while simultaneously preventing a different pollinator from accessing the pollen. The tunnel through which an animal must access nectar can vary widely in length and diameter, which prevents the plant from being cross-pollinated with a different species (Figure 2.2.5).

Gametic Isolation

Gametic isolation is where the sperm of one species is unable to fertilize the egg of another species. This can occur due to chemical incompatibilities or differences in reproductive proteins. For example, many aquatic species (e.g. many fishes, mollusks, jellyfish, sea urchins) release their gametes into the water. Fertilization only occurs if the sperm and egg are from the same species because their surface proteins must match precisely for fusion to happen.

Postzygotic barriers:

A postzygotic barrier occurs after zygote formation; this includes organisms that don’t survive the embryonic stage and those that are born sterile.

Hybrid Inviability

Hybrid inviability is when the hybrid offspring fails to develop properly or dies at an early stage. This is often due to genetic incompatibilities between the two parent species. For example, when certain species of frogs interbreed, the resulting embryos may not survive past early developmental stages, preventing the continuation of the hybrid line.

Hybrid Sterility

Hybrid sterility is where the hybrid offspring is healthy and reaches adulthood but is sterile, meaning it is unable to reproduce. A well-known example is the mule, which is the offspring of a horse and a donkey. Although mules are strong and capable animals, they are generally sterile because of differences in the number of chromosomes between their parents, which disrupts normal gamete formation.

Hybrid breakdown

Hybrid breakdown occurs when the first-generation hybrids are fertile and viable, but their offspring are weak, sterile, or otherwise less fit. This is seen in some species of cultivated rice, where the initial hybrid plants can reproduce, but their descendants often show reduced fertility or poor growth.

Knowledge Check

Text Description

- A group of organisms that share similar physical traits

- A group of organisms that can interbreed and produce fertile offspring

- A group of organisms that are genetically identical

- A group of organisms that live in the same geographical area

- It only applies to plants

- It does not apply to asexual organisms or fossils

- It ignores genetic diversity within populations

- It assumes all organisms interbreed

- Habitat isolation

- Temporal isolation

- Behavioural isolation

- Mechanical isolation

- Male fireflies use distinct light patterns to attract females

- Two species of frogs breed at different times of the year

- Male damselflies of different species have differently shaped reproductive organs

- Two species of birds do not mate because of different courtship rituals

- Hybrid sterility in offspring

- Interbreeding between species due to incompatible mating behaviours

- Fertilization due to chemical incompatibilities between sperm and egg

- The formation of hybrid offspring

- The hybrid offspring are sterile

- The hybrid offspring do not survive past early developmental stages

- The hybrid offspring are weaker but can reproduce

- The hybrid offspring produce fertile descendants

- The hybrid offspring fail to develop properly and die early

- The hybrid offspring are sterile and unable to reproduce

- The hybrid offspring are weak but still fertile

- The hybrid offspring break down and become unfit over generations

- Mules, the offspring of horses and donkeys, are fertile

- Hybrid plants in cultivated rice are strong but cannot reproduce

- Hybrid frogs from different species survive but have reduced fitness in future generations

- Hybrid offspring in cichlids are viable but unable to produce offspring

Answers:

- b. A group of organisms that can interbreed and produce fertile offspring

- b. It does not apply to asexual organisms or fossils

- b. Temporal isolation

- c. Male damselflies of different species have differently shaped reproductive organs

- c. Fertilization due to chemical incompatibilities between sperm and egg

- b. The hybrid offspring do not survive past early developmental stages

- b. The hybrid offspring are sterile and unable to reproduce

- c. Hybrid frogs from different species survive but have reduced fitness in future generations

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat

Prompt: Create 8 multiple-choice questions using the following content