Trace

by Tia Carey

Abstract:

My chapter investigates AI’s ability to replicate the strategies of artists Lorna Simpson and Robert Frank, creating image subjects which embody representational systems of identity, and weaving in visual and narrative ambiguity. With reference to the theories of Rolande Barthes (intertextuality) and Paul Ricoeur (trace), and the research of Dafydd Hughes and Tabita Rezaire, I will describe the machine’s performance of existing socio-cultural narratives, and the dialogic nature of human interpretation of AI art. I am interested in exploring the interpretive subtext, and the necessity of a reader with a strong contextual awareness and ability for a multiplicity of understandings. My larger observation is that the digital world is solely capable of reflecting our current ethical, cultural, economic, social, and geopolitical realities, of which each AI generated image is a trace.

Many of the questions I ask in this paper run parallel to this question: which artists would I seat at my dream dinner table? The pressure to make a good seating plan is immense. To be resurrected only to be sat next to an abrasive dinner guest would certainly cause resentment towards the host. Questions about compatibility would be necessary. Who shares perspectives and values? Whose personality meshes well? Who can mediate? Who sits next to the obligatory but eccentric guest, artificial intelligence?

Lorna Simpson would be at the top of my list. I see her art as witty and thoughtful, presented by a rapturing storyteller. She presents photographs pairing image and text, full of historical references and social commentary. They ask questions that bring awareness to the viewer’s body and social stratum, as well as their own lived history. Her works often visualize the representational systems which define black womanhood rather than individual black women, speaking to the (art) historical denial of black women’s subjectivity.[1] Machine learning follows a similar process to Simpson’s work, but without understanding or purpose. I wonder about the discussion that would ensue between these two guests.

Robert Frank could be seated on AI’s other side. Frank strikes me as somebody who would not rush to fill awkward silences, and who would always let you finish your thought. His most famed work is The Americans, a photo book which documented his travels as a newcomer to America in the 50s. This postwar era was a vulnerable moment for America’s identity, and photographers were looked to as proponents of a clear, strong American image. The content and formal qualities of Frank’s images were not explicitly favourable towards the nation, or explicit in any sense; they presented America as heterogenous and containing much moral grey area. AI, with its jumbled and alien images might find an equal in Frank’s obscured, grainy, and skewed compositions. As two outsiders to their images’ subject matter, they can both bring clarity through their images’ incongruence with insider narratives. The filmic sensibility of Frank’s images might parallel the infinite AI generation of images from a given prompt, both hinting at the story of their creation and to the possibility of alternative narratives.[2]

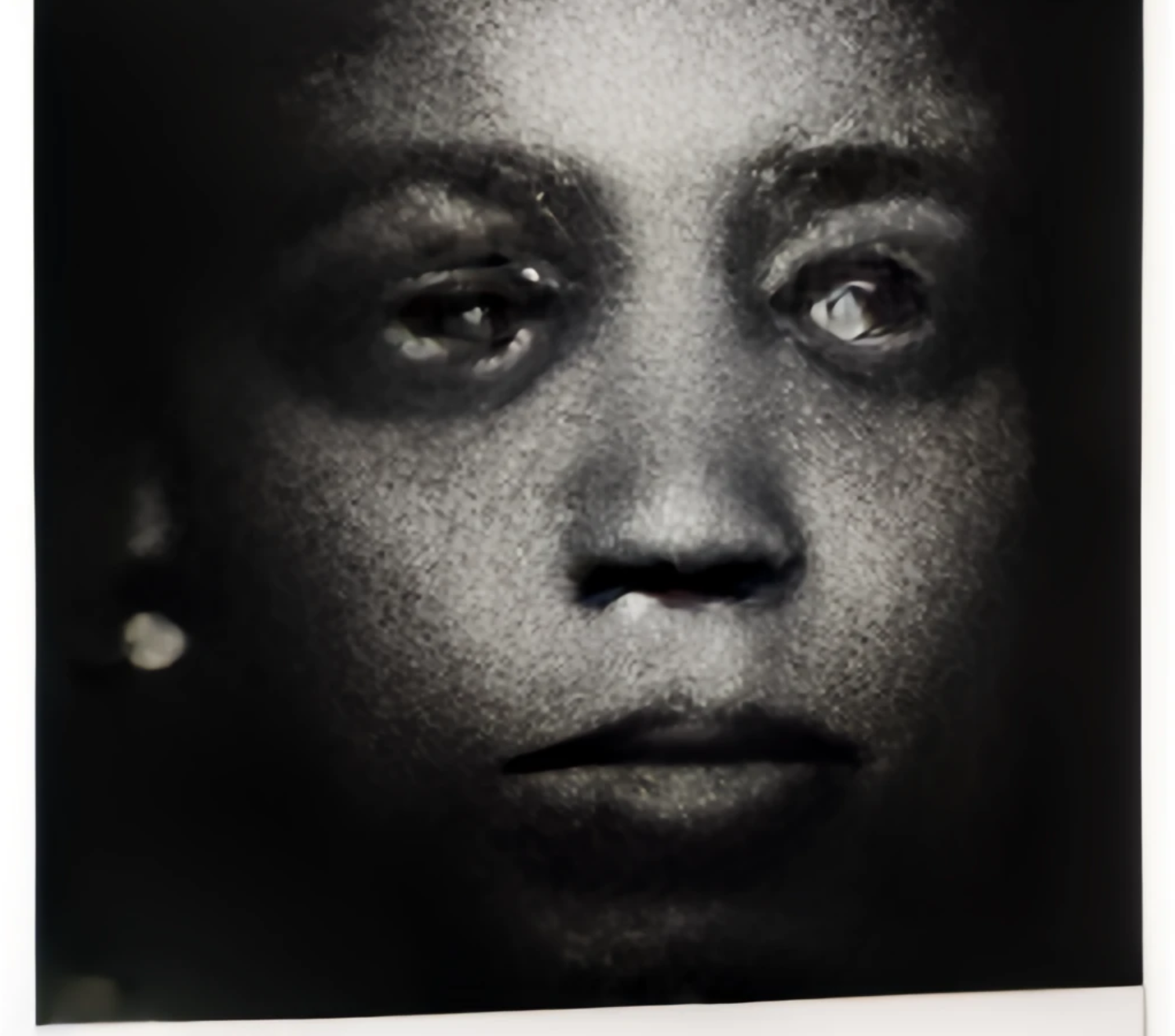

My question was initially what it would look like for Simpson and Frank to work together or to interact; I was curious how they might represent one another. My images were generated using DALL-E mini by craiyon.com. Having never generated an image using AI before, I wasn’t sure what questions to ask. I started with the names of each artist individually, to gauge the generators ability to replicate style and render an image that was coherent, interesting, and pleasing to the eye. My prompts for “Lorna simpson” generated a grid of kinky hair, hair shaped inkblots, and ransom-note faces, which I realized were a reflection of her recent collage work, and not of the machine’s inability to render faces. “Robert Frank” prompted images of ghostly black and white faces leering out of hazy shadows, with many instances of a particular texture, which looked as if very dry skin could ripple like sand. The results of “lorna simpson and robert frank” weren’t as fruitful as “Robert frank and lorna simpson”, which gave some a striking insertions of Simpson’s black female figure into the world of The Americans. Alongside them were several portraits of the two artists in shadowy rooms, with cut and pasted facial features and textured skin. Simpson was recognizable by her hair, and Frank by his glasses, wide brimmed hat, and tie. My first run of “Robert frank and lorna simpson photograph” generated the most real looking human I’ve seen from DALL-E so far, in Robert frank and lorna simpson photograph (Fig. 1). Her marred eyes reveal her inhumanness while allowing her additional expressiveness with which to convey human emotion. I was drawn to the emaciation of the figures in these types of images, and compelled to examine how AI “understood” these people.

I started thinking of the traits the work of Frank and Simpson shared; two photographers who played with ambiguity, speaking through that which is not explicitly said or shown. Both of their work also states their awareness of the narratives which make up race and nation in America. They question whether representation in a photograph could humanize the subject to the viewer.

As a dead white man who occasionally photographed black women, and a black woman who isn’t in the habit of photographing white men, how would they speak about each other? “Lorna Simpson photographed by Robert frank” produced a range of of portraits which appropriated Simpson’s collage style in Frank’s name. My chosen photo, Lorna Simpson photographed by Robert frank (Fig. 2), might be Simpson without eyes, as if they had been cut out of the “photo”, revealing a white sheet of paper underneath. This is a distinct departure from the compelling eyes in the last image. The light source apparently shining in from the left side of the composition make this Simpson’s expression hard to read. The left side of her face is mostly obscured. Her mouth might be slightly open in an expression of unease, or she may have fuller lips marked by a distinct shadow. What might be another harsh shadow around her eye could also be a bruise or a tired dark circle. Aside from a patch of white on the left side of her face, the background is also dark, bleeding out onto the white border. Given the AI’s seeming association of Simpson’s name with natural black hair shape and texture, this might be her hair. Or, following the logic of this being a collage, this could be the ripped edge of the photo.

I also tried the names of their artworks with the other’s name attached: “Robert Frank necklines” or “Lorna simpson the americans”. Robert Frank guarded conditions (Fig. 3) seemed to recall the gathered roadside figures Frank’s Car Accident, U.S. 66, between Winslow and Flagstaff, Arizona. Hauntingly, the covered body at their feet in Frank’s work is exchanged for the obscured faces of the figures themselves. Although their backs are turned in Simpson’s signature motif, they appear to be wearing similar hats before a similar grassy field. The same high horizon is figured in both compositions, although the viewer is now frighteningly positioned where the dead body might have been in relation to the standing figures. The houses in the background are now dots on the horizon. Perhaps, these are not the same figures. They now more closely resemble the pyramid of elderly figures in St. Petersburg, Florida. A headcount locates the brimmed hat with a ribbon, the cap, the wrapped hair, and the white curls. In this case, one of the figures still remains unaccounted for, as with the covered body by the roadside.

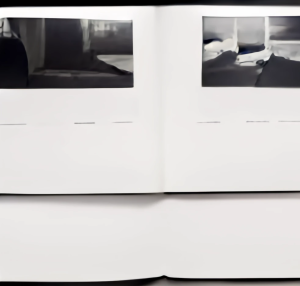

This same prompt also gave me the only image which showed the photograph on the page of an entire book (Fig. 4), presumably in the style of The Americans. Another meta-layer is added by a second open book stacked underneath. The two “photographs” are black and white, without any immediately recognizable subject matter. The one on the left might contain a door, a suitcase and the wing of a plane. The one on the right might be a transport truck on the road, next to the head of a windmill. Below them both is a row of thin black dashes; they hint at the appearance of words on a page. Although it seems unlikely to me that DALL-E was actually drawing from photos of Simpson’s work, I see the grid layout of Guarded Conditions in the layered books and side-by-side images. The Americans is formatted with only one photo in every spread, so this is not the direct visual referent here. The line of “text” mirrors the sequence of phrases in Guarded Conditions. The white pages also stand in for the white gallery wall onto which Simpsons text and grid of images is hung. What I didn’t realize until much afterwards was that many of the generated images had white borders, some of them slanted as if being viewed on a turning page, or held up at an angle to view the skewed composition straight on.

On the track of self reflexivity, I decided at this point to ask the AI to address it’s own limitations as outlined in a disclaimer on the web page:

“While the capabilities of image generation models are impressive, they may also reinforce or exacerbate societal biases. While the extent and nature of the biases of the DALL·E mini model have yet to be fully documented, given the fact that the model was trained on unfiltered data from the Internet, it may generate images that contain stereotypes against minority groups. Work to analyze the nature and extent of these limitations is ongoing, and will be documented in more detail in the DALL·E mini model card.”

Interchanging the names of the artists with phrases from the disclaimer such as “stereotypes against minority groups” didn’t produce much that was distinct from the previous images. Having assembled a few pages of my own “photo book” through the process of repeated AI generation, I had reached the departure point from which I would analyze my selected image (Fig. 2).

Firstly, the mask-ification of the black woman calls to mind Picasso’s cubism. Within the act of appropriation of Simpson’s style, there is a mirror of his appropriation of African masks in the appropriation of her face. In her literal objectification, even her gaze is taken from her. She is not granted subjectivity with which she might respond to her viewer, her creator, or her circumstances. What does it mean to be reduced to a face without a person behind it? Whereas the first image of the child with the tearful eyes was able to embody pain and intimate emotion, this face has no soul or identity behind it. Many photographers operating during the postwar era saw photography as an avenue to bestow respect and dignity upon its subjects; it was thought that the truthful record of a person’s likeness could humanize them. Frank’s stylistic manipulations created vague, unsettling, or even threatening portrayals of subjects which put into question the ability presupposed of photographers to embody an objective vision. In fact, The Americans asserts the need for such grey area in order to encompass the realities of violence and fear faced by American people.[3] Erik Mortenson argues that through Frank’s visual style of “disrupts” the viewer’s recognition of the human figure. Instead of identifying with the subject, the viewer must question the circumstances of the disjunction, which is at once visual and cultural[4] The techniques which he uses to obscure or disassociate the figure, such as grain, shadow, or blur, entice the viewer in for reasons other than shared humanity.[5] Looking back to the image of “Lorna Simpson”, there is a suggestion of Frank’s hand in the concealment of her face. Not only is her face partially in shadow, but even visible features such as the jawline, chin, nose bridge, eyebrow, and forehead are blurred. Only at the brightest point of her right cheek are the details of her skin visible.

Simpson’s work is also no stranger to such ghostly figures. Lorraine O’Grady notes that Simpson’s black female figures have “every aspect of subjectivity both bodily and facial occluded, except the need to cover up itself.”[6] For black women, she says, subjectivity is not to be theorized upon until it is expressed. To make this process more and less convoluted, neither the subject nor the creator of this image is a black woman, although the human viewer is told otherwise. While Lorna Simpson is intentional in her restriction of self expression in her works, the AI cannot have intention or self expression either way. As Simpson does, the AI can identify visual patterns, and form associations between image and text. It can produce images that are instances of this algorithm based on a specific dataset, working exclusively from images represented in this larger system. What it cannot do is know what it feels like to be reduced to an instance of a type, and the humanity that is not granted by this experience. It cannot know what it means to be racialized, although it can identify race. It cannot reflect on how or why these classifications are designated, or question who, when, why, and how they were established. But the generated images can ask these questions of the viewer, so long as they are equipped with the understanding of the process of image generation. This is where the theorization which O’Grady refers to may actually fit in. According to Roland Barthes line of thinking in Death of the Author, the absence of an identifiable human creator liberates the AI image from a single signification.[7] The AI image has no origin or one true meaning; its ideas can only be expressed through an infinite reuse of pre-existing ideas which one can only hope to pull apart the threads of.[8]

In an analysis of his own similar explorations of Robert Frank’s work using AI, Dafydd Hughes points towards this shift of agency given to the document itself. In the relation of the author, the text (or AI image) and its content are given roles in the act of reading; without an author’s imposition, the document and reader develop meaning in conversation with one another.[9]

He also points towards Paul Ricoeur’s trace as a helpful descriptor for such documents. The trace is both the physical mark which documents the passage of a moving being, and the significance of its relationship to time and place [10] The dual meaning of the trace is invoked by the evidence of a past event intersecting with our present day, posterior, understanding of it, as relative to our own time.[11] Hughes elaborates on the importance accorded by Ricoeur to honouring the connections of these documents to the people and events which created them: an archive preserves each document relative to its contextual history whereas a database severs the document from this relationship with time.[12] The database, presuming the document is something to be simply understood, does not allow for the dialogic relationship between document and reader which is underscored by both Barthes and Ricoeur. After all, the viewer, as classified by Barthes, is someone who holds within themselves all the “traces by which the written text is constituted.”[13] This type of reading is most conducive to the works of Frank and Simpson, which draw their significance from the ambiguity which allows for the multiplicity of a viewers’ understandings.

But does this apply to their work as interpreted by AI? The machine has only a database to work from, and cannot take on the act of interpretation and engagement with its dataset. While it cannot take on the task of reading, it can raise questions about the act of reading itself, by pointing back to its own dataset and algorithm.[14] With awareness of the biases disclaimed by the generator’s creator, I was led to Tabita Rezaire’s Deep Down Tidal, a video installation which I recently viewed at the Helsinki Biennial. It outlines a phenomenon described by the artist as “electronic colonialism,” which is the expansion of Western imperialism into the digital realm, in the absence of physical land to conquer. This is facilitated by the importation of hardware, software, engineers, and protocols into colonized countries, which favour Western knowledge and create dependency.[15] The internet is not decentralized or universal, argues Rezaire, the internet is the physical cables on the sea floor which follow former slave trade routes.[16] Interestingly enough, the etymology of the word “robot” stems from an Old Czech word for “slave.” [17] Rezaire also notes that the water which holds these internet cables functions as an archive, which carries traces of its passages.[18] Digital data systems are only able to function within the architecture of violence upon which they are built; the virtual can only reflect the real world’s geopolitical, social, cultural, and economic realities. Humans are ourselves technological entities, evolving through and alongside technology since time immemorial.Joanna Zylinska, "A So-Called Intelligence," in AI ART: Machine Visions and Warped Dreams (London: Open Humanities Press, 2020), 27. http://www.openhumanitiespress.org/books/titles/ai- art/[/footnote ] When reading these AI generated images, it is important to consider one’s obligation to history. The work of Lorna Simpson and Robert Frank when interpreted by an agent without such an obligation or ability allows the viewer to take stock of how they may participate in the process of reading. A good dinner guest assesses which questions to ask at the table, which threads to pull, and when to take anecdotes with a grain of salt. A good reader will similarly ask questions and put things into perspective with all the good judgement necessary to properly engage in dialogue with these images, knowing that they will also engage in dialogue with us.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Tia Carey is a fourth year undergraduate student at the University of Ottawa, majoring bilingually in Art History with a minor in Digital Cultures. It is her second year working on the Canadian BIPOC Artists Rolodex within the University’s Department of Visual Arts, as an administrative and research assistant. She is one of the minds behind the installation of the exhibition Planting Roses in January, as well as the curation of the more recent Plato’s Lounge.

- Nika Elder, “Lorna Simpson’s Fabricated Truths,” Art Journal 77, no. 1 (2018): 30–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.2018.1456248. ↵

- Ann Sass, “Robert Frank and the Filmic Photograph.” History of Photography 22, no. 3 (1998): 247–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/03087298.1998.10443885. ↵

- Erik Mortenson, “The Ghost of Humanism: Rethinking the Subjective Turn in Postwar American Photography.” History of Photography 38, no. 4 (2014): 418. https://doi.org/10.1080/03087298.2014.899747. ↵

- Mortenson, “The Ghost of Humanism," 421-22. ↵

- Mortenson, “The Ghost of Humanism," 425. ↵

- Lorraine O’Grady, “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity,” in Art, Activism, and Oppositionality, ed. Grant H. Lester (New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2020), 275. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822396109-017. ↵

- Roland Barthes, "The Death of the Author", in Image, Music, Text (1977), 147. ↵

- Barthes, Death of the Author, 146-147. ↵

- Dafydd Hughes, “Every face in The Americans: Faces from photographs by Robert Frank, selected by iPhoto.” (PhD diss. Ryerson University, 2011), 13 ↵

- Paul Ricoeur. Time and Narrative, Vol. 3. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988), 119-120 ↵

- Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, 120 ↵

- Hughes, Every face in The Americans, 20 ↵

- Barthes, The Death of the Author, 148 ↵

- Hughes, Every Face in The Americans, 30 ↵

- Tabita Rezaire, "Deep Down Tidal," video installation, 18:44, December 27, 2017, https://vimeo.com/248887185 ↵

- "Deep Down Tidal." ↵

- Rezaire, "Deep Down Tidal." ↵

- "Deep Down Tidal." ↵