Freedom

by Dana Mehdipour-Haidari

Abstract:

The Iranian movement, Women Life Freedom is explained, accompanied by the dark realities happening to the people of Iran. Their technological and artistic methods of sharing their reality with the world, despite the limits they face from the oppressive restrictions of the country’s legal system, are brought to light. This reality then intersects with how artificial intelligence’s interpretation, more so its misinterpretation of Iranian women’s representation and their combat to attain freedom is a danger for their movement through the analysis of AI-generated artwork corresponding with different prompts. Lastly, recommendations for the future of artificial intelligence are made to reduce the gendered prejudice and racially discriminatory foundations of AI.

Women.

Life.

Freedom.

A chant that has burned the throats of millions of Iranians across the world. The death of young Mahsa (Jina) Amini, a kurdish woman, in the custody of Iran’s morality police under arrest for “improperly” wearing her hijab, ignited the flame of the movement after decades of oppression.[1] Through the 1979 revolution, Iran transitioned from being a monarchy to a theocracy, enforcing a mandatory dress code for women, where only their visage could be visible in public and further embedding gender segregation in public spheres.[2] The country’s laws regarding gender are derived from the idea of the nation defending the body of a woman, inspired by Iris Marion Young’s theory, “logic of masculinist protection” and Foucault’s “pastoral power”.[3] The hijab is not inherently oppressive but to women in Iran who are not given the choice but are rather forced to wear the hijab, the dress code over the decades has become the symbol representing all of their bodily and behavioral restrictions. To put it in perspective, eating a fruit for example is not oppressive if you can eat the fruit whenever you want. However, if you are forced to only eat oranges and do nothing else, that changes the meaning of the fruit to you. You cannot dance or sing, you must eat oranges. They tell you, that if you don’t eat your oranges you will be punished, arrested, tortured, killed. Then, the simple act of eating a fruit becomes oppressive.

Iranian women have rebelled since the conception of the Islamic Republic of Iran, changing their tactics with the digital age of technology by building small movements like Alinejad’s White Wednesday campaign (2017), where the journalist motivated women in Iran to wear white on Wednesdays and post their “acts of defiance” on social media, using the hashtag #WhiteWednesdays.[5] A year later, another movement was started by Vida Movahed when she removed her hijab on Enghelab Street in the nation’s capital, she stood on a utility box, waving her hijab on a stick and was arrested but swayed other women to follow her lead, sharing their imitations online, showing how one person’s protest fuels “collective action”.[6]Artists have also contributed by sharing their art on multiple online platforms as an act of defiance to curb censorship.[7] Built upon the previous resistance of the people, the Woman, Life, Freedom movement officially commenced in September 2022,[8] where women and men took to the streets and the internet to protest. Every day for an entire year, inside and outside of the country people protested. Iranians protested for women’s rights, for the right to choose, and for democracy. They cut their hair publicly, sang, and danced in the streets. In return, they were tear-gassed, shot, had their businesses shut down, arrested, and executed but they persisted.

I recall the day after Mahsa Amini’s death, there were already one or two artworks circulating on social media but by the end of the week, there were thousands used to raise awareness and plastered on placards at protests. Art outside of the digital space was also used as a tool for activism, as done by an anonymous artist group, who unfurled red banners, on which the words ‘women life freedom’ and Mahsa Amini’s face were drawn, in influential institutions like the Guggenheim Museum[9] and San Francisco’s MOMA.[10]

Simultaneously, as technology aids the people of Iran to have their voices heard, the government suppresses them by restricting the internet and ordering nationwide blackouts.[11] As women stopped complying with the mandated dress code, the government put up cameras to find the rebelling women and closed down the companies and stores that do business with unveiled women.[12] In fact AI recognition applications are used by the state to impose “morality codes”, for example over a million women were sent a mass text informing them that if they were caught on film not wearing the hijab, their cars would be taken from them.[13] Now considering all of this, we come face to face with the intersection between the Women, Life, Freedom Movement and Artificial intelligence. Verity Babbs describes art created by AI as, “dependent on systems and a corpus of visual artifacts that still center the white heterosexual male gaze – by virtue who is represented in the tech design and development world, and who does content moderation,” furthermore generating disrespectful and racist depictions.[14]

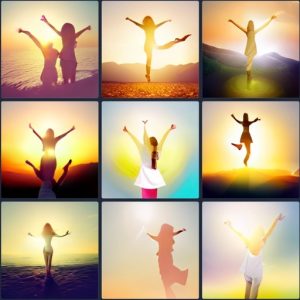

Which raises the question, how does AI Art represent the Women, Life, Freedom Movement? When the words, “women life freedom” were inputted in DALL•E mini, my presumption was for AI to generate images related to the movement, such as anti-regime protests. I was not expecting to obtain what ultimately appeared like the mesh between a gentrified yoga and yogurt/menstrual product ad (see Fig.1) of a feminine body jumping into the sunset. Perhaps this expectation derived from my own bias as these three little words hold a great significance to me. So the prompt underwent fine-tuning. This was a mentally laborious task as the generator does not necessarily produce the work one has in mind went attempting to create AI art. A justifiable critique AI art receives is that it is not real art because AI produces the work, however, this cannot be done without a human sitting down and manipulating words. The process was vaguely reminiscent of the method in which the song writer Shervin Hajipour used tweets posted by Iranians explaining why they were protesting, composing the lyrics of the song with the tweets of the people’s real concerns. His song Baraye was the anthem used at protests for which he was arrested for “promoting riot” and “disturbing national security”, serving time in prison.[15] A few months later in 2023, he was awarded a Grammy by the First Lady of the United States for “Best Song for Social Change”.[16] Out on bail in early March of 2024, on the day of the first elections occurring after the movement, Hajipour took to social media to thank his lawyers for their support and it was from Hajipour’s post that the public learned about his three-year sentence as the country’s media did not address his imprisonment.[17] Similarly to how Hajipour used tweets to make his song, in this research prompts are put into AI in an attempt to make representative art related to the movement.

From here, I experiment by adding “Iran” to the prompt alongside significant dates such as 1979 (introduction of dress code), 2022 (Mahsa Amini’s death), 2023 (the year of protests), and 2024 (present-day), running the generator multiple times with the same prompt to achieve a different array of results.

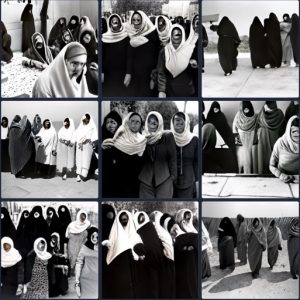

Women Life Freedom Iran 1979

Although the Woman Life Freedom Movement did not exist in 1979, this does not signify that women were not actively fighting to preserve and gain their rights back then. I ran the AI system multiple times but all the results were similar, as shown on the third run (see Fig. 2), in black and white, faceless groups of covered feminine bodies roam aimlessly. It is a bleak and hopeless representation, frankly underwhelming because the image in my head was Hengameh Golestan’s photograph from March 8th, 1979 (see article), capturing the endless stream of people protesting against the mandatory hijab, fists raised in the air, emotion and conviction apparent on their faces.[18] On International Women’s Day, three thousand women protested in Qom where Khomeini, the former Supreme Leader, lived.[19] Additionally, that same day “tens of thousands of women” protested in Tehran in front of the Prime Minister’s office and continuously did so for six days straight.[20] On the International Women’s Day protest, Psychoanalysis and Politics, a feminist group from France joined the march and interviewed Iranian women, creating a heartfelt 12-minute documentary (can be watched here).[21] The documentary shows the reality of 1979, veiled and unveiled women marching to support each other for the choice over their bodily autonomy.

[Dana Mehdipour-Haidari], Woman Life Freedom Iran 1979, January 22 2024, DALL•E mini.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Women Life Freedom Iran [2022, 2023, 2024]

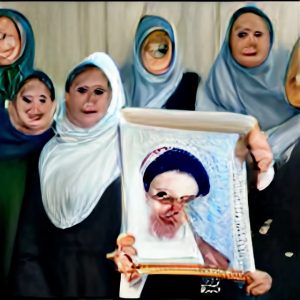

Switching the date in the prompt from 1979 to 2022 made an immediate change. Right away it is apparent that the images are no longer in black and white but in colour. Although still distorted, the women’s faces are more defined and human-like compared to the 1979 rendition. What shocked me was the presence of the Supreme Leader Khomeini (1979- 1989) and Khamenei (1989-present), apparent by their turbans and white beards, they can be identified by their different face shapes of the figures. Khomeini is lurking in the background (see Fig. 3) and Khamenei is in the foreground, in front of a row of women (see Fig. 4). Yet the women in this prompt wear the black chador, a symbol of the 1979 Islamic revolution and are smirking, almost smiling in the presence of the Supreme Leader. In reality, during 2022, Iranian women were not smiling. They had just taken the streets after twenty-two-year-old Mahsa Amini’s murder, chanting for justice and freedom, chanting for the abolition of the theocracy, chanting for Khamenei to be put on trial and charged for his crimes. So why would Artificial Intelligence not show a movement that spread to a global scale? Perhaps AI related the country’s name in the prompt to the Supreme Leader of Iran. What is certain is that once again, AI misinterpreted the prompt, pushing a false narrative.

[Dana Mehdipour-Haidari], Woman Life Freedom Iran 2022, February 8 2024, DALL•E mini.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

[Dana Mehdipour-Haidari], Woman Life Freedom Iran 2022, February 8 2024, DALL•E mini.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Not much changes when the year is switched to 2023, except in Fig. 3 the women wear colourful and bright hijabs, continuing to smile, standing with their backs to a curtain as though at a ceremony, proudly holding a scroll with a disfigured portrait of the Supreme Leader. I can contest that after a year of continuously protesting everyday, Iranian women were not content. They were angry and grieving. By 2023, the Human Rights Activists News Agency claimed that at least 500 people were killed by the hands of the country’s police and 20,000 people arrested.[22]Women were not comoderating Khamenei by holding up his portrait, in reality they were burning them. Khamenei as well as the former Supreme Leader Khomeini’s portraits are hung in every classroom and printed on the first pages of textbooks, a constant reminder of their authority. Iranians, who as a collective greatly value education, ripped the pages from textbooks with the dictators’ pictures, shredding the photos to pieces. I recall during the peak of the protests, clips circulating of brave young girls standing on chairs to reach the framed portrait of the current and past Supreme Leaders to remove the photographs from the front of their classrooms. Schoolgirls participated in their own acts of resistance, by removing their hijabs, organizing walkouts, and protesting in their schoolyards. In return, the government targeted schools, poisoning 1000 schoolgirls across various provinces with an unidentifiable gas, which the government denies doing with the aid of propagandistic media, belittling the victims severe symptoms.[23]

[Dana Mehdipour-Haidari], Woman Life Freedom Iran 2023, February 8 2024, DALL•E mini.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Unfortunately, altering the prompt to 2024 to see its interpretation of the present was futile, as it portrayed women wearing black and colourful hijabs, disturbing large grins encompassing their faces. There is no existence of the Women Life Freedom Movement in these AI images mentioned above, exceeding inaccuracy as the movement left an unavoidable mark on Iran’s societal and behavioural culture.

President Raisi, in February 2024, approved of a bill, despite the financial ramifications of its adoption[24], granting up to 10 years of imprisonment for not abiding by the mandatory dress code, stating that not wearing a hijab is equivalent to “nudity”, furthermore under the scope of the “Bill to Support the Culture of Chastity and Hijab”, mocking the veil can lead to paying damages, imprisonment and/or banned to travel.[25] Today in 2024, the laws have only become stricter but the women have only gotten braver, prioritizing their path towards gaining freedom.

[Dana Mehdipour-Haidari], Woman Life Freedom Iran 2024, February 8 2024, DALL•E mini.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Frustrated, I thought, these AI images are a horrible representation of modern Iranian women, who are from a country with so much cultural, ethnic, and religious diversity to be restricted to one limited monolith. Truthfully, it is an injustice to Iranian women’s courage. This made me further think about the term ‘modern women’ and how it is used. We hear, “Oh, she’s such a modern woman”.[26] What does that even mean? Obviously being a modern woman changes constantly as society evolves but Oksana Repka proclaims, “The modern woman has her own voice”. So I tested “modern Iranian woman” as a new prompt and AI produced Fig.7, showcasing all veiled women, which is no longer the case as many risk their lives every day by not complying with the compulsory dress code. Even women who do wear the hijab do not veil themselves in Iran the way AI believes. Iranian women have been so restricted over the past four decades that when it comes to self-expression in reprise they take their fashion very seriously and AI’s interpretation is inaccurate as its portrayal of the worn hijab is not in the “Iranian style”, which is fit “ looser” and the outfits are not “trendy”.

[Dana Mehdipour-Haidari], Modern Iranian Women, February 10 2024, DALL•E mini.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

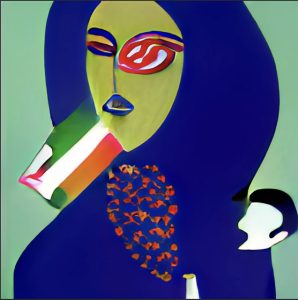

Nonetheless, the prompt was vicariously edited, transforming into “Women Life Freedom Revolution in Modern Art Style” and the results were surprisingly refreshing, so I ran the system several times. Most of the AI images created with this prompt carry similar themes, the colour red, white, and green are predominant, as well as the motif of the Iranian flag. Nevertheless, Fig. 8 attracts attention by differentiating itself by having the primary colours of the AI artwork being navy and ochre. A woman veiled in navy garments with a strand of hair peeking out has tears cascading her pale face with an indistinguishable gaze while holding a smaller figure. That other figure can be interpreted as a child, who is also covered but plastered with the colours of the country’s deconstructed flag. Is this hinting at the law that girls as young as nine years old must follow the compulsory dress code? A navy shadow loiters behind them. Is it the woman’s shadow? Is the shadow of the morality police following them? Overall the work leaves the viewer with more questions than answers but undoubtedly the glazed fear of the navy woman is apparent.In an art historical context one can draw a resemblance between the presence of the background shadow of Fig. 8 to the looming shadow of Manet’s Absinthe Drinker (1859) and his rendition of modernity.[27] However it was brought to my attention the parallels between the composition of Fig. 8 and the Icon of the Virgin and Child, Hodegetria variant (Byzantine or Crusader).[28] Similarly to Fig. 8, the thirteenth century artwork presents a veiled mother holding her infant to her chest, her gaze described as “pensive” and aware of her boy’s “future suffering”.[29] Much like the Icon of the Virgin and Child, in Fig. 8 the mother clings to her veiled child, assuming she is a girl, her tears indicate the griefful knowledge of a familiar future in which her daughter will have to navigate her life with the bitter restrictions emplaced on the woman in Iran. The shadow of their sorrows chasing them. Overall the work leaves the viewer with more questions than answers but undoubtedly, the glazed fear of the navy woman is apparent.

Another AI artwork that caught my attention is Fig.9, another veiled woman with a green face with an upside-down Iranian flag protruding from her chin, and a masculine head with an open mouth talking into her side. It appears that AI pulled inspiration from the flatness of Matisse’s Blue Nudes series[30] and from Picasso’s style of abstract portraits to generate the face of the figure, showcasing that even when the subject is non-western, AI art is generated to favour western art, even possibly filtering out non-western art style as there is a lack of Iranian influences throughout the artworks. Nonetheless on Fig. 9’s torso there is a splattered red motif resembling the injuries victims sustained from getting shot as the pellet wounds would scatter across their bodies. There is a great emphasis on Fig.9’s right eye, almost as if swirling with blood. This reminded me of how the authorities would purposefully target the eyes of protestors, not less than 500 people sustained eye injuries only in Tehran during an approximate one-year period while many did not seek medical treatment to avoid the risk of getting arrested at the hospital.[31] Ghazal Ranjkesh, a law student, was the first to post about her situation (Ghazal’s picture), opening the gates for victims in the same position to find a supportive community.[32] Ghazal took to Instagram to write her statement, “The sound of the eyes is louder than any scream.”[33]

[Dana Mehdipour-Haidari], Women Life Freedom Iran Revolution in Modern Art Style, February 8 2024, DALL•E mini.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

The next AI artwork (see Fig.10) is of a faceless woman in a black veil, throwing her red arm in the air as though setting fire to the country’s flag, which burns, rupturing the tableau of the Supreme Leader behind her while he remains untouched. This shows how even in the fight for freedom, the roots of the oppressor are difficult to weed out.

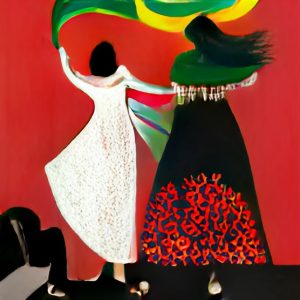

Up until this point, all of the artworks created by AI produced images exclusively of a veiled woman. It took six runs to show an unveiled woman (see Fig. 11). Two feminine figures stand with their backs to the viewers, the one on the left wears a white dress, symbolizing peace, waving a green flag while her supportive hand rests on the other woman’s back. The wind blows the woman to the right’s hair and a trimmed scarf rests comfortably on her shoulders as if she has retired her hijab. She stands tall even though her skirt is stained in a similar red motif from Fig.9 assuming she was injured during a protest. Fig. 11 portrays the resilience and support nourished within the Women Life Freedom movement. This artwork resembles what I initially had in mind when beginning the research as it holds a vague resonance of art made by Iranian artists that circulated during the movement.

[Dana Mehdipour-Haidari], Women Life Freedom Iran Revolution in Modern Art Style, February 8 2024, DALL•E mini.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

As for representing the Women Life Freedom movement, although the AI art became hopeful with the last prompt, it is not the most reliable tool to render such a delicate topic without perpetuating misleading and destructive narratives that can fire back on the growth of the movement. Especially the earlier AI creations which produced false images that align rather with the Iranian government’s notions and the West’s one-dimensional perspective of Iran’s multilayered issues. This can be problematic as there is more development on AI search engines like Perplexity becoming an alternative for Google, causing trouble by making mistakes and spreading misinformation.[34] Susan Leavy’s research on gender biases regarding Artificial Intelligence confirms that “the over-representation of men in the design of these technologies could quietly undo decades of advances in gender equality.”[35] Leavy encourages the involvement of women in the field of AI, deeming them “essential” to promote “fairness”.[36] I would push it one step further by encouraging women of colour and people from other minority groups to bring an intersectional perspective to the future of AI in an attempt to prevent its discriminatory biases.

Regardless, no one but Iranians can capture the utmost true artistic portrayal of their struggles as their art, unlike AI, is founded on their real-life experiences. Ghazal Ranjkesh expresses, “The pain is unbearable but I’ll get used to it. I will live my life because my story is unfinished. Our victory is not here yet but it’s close,”[37] beautifully reflecting the sentiment of the people of Iran.

[Dana Mehdipour-Haidari], Women Life Freedom Iran Revolution in Modern Art Style, February 8 2024, DALL•E mini.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

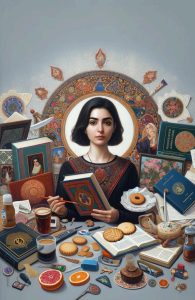

Biography:

Dana Mehdipour-Haidari is a third-year student at the University of Ottawa, majoring in art history and minoring in law. She is interested in exploring her Iranian culture through the arts, further connecting her to her roots. If she is not obsessively writing or flipping through a novel, she can be found baking cookies.

- Mehan, Asma. “Digital Feminist Placemaking: The Case of the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ Movement.” Urban Planning 9 (2024): 8, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.7093. ↵

- Mehan, Asma. “Digital Feminist Placemaking: The Case of the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ Movement.” Urban Planning 9 (2024): 4-5, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.7093. ↵

- Mehan, Asma. “Digital Feminist Placemaking: The Case of the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ Movement.” Urban Planning 9 (2024): 5, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.7093. ↵

- “Zan. Zendegi. Azadi. Woman, Life, Freedom.” Zan. Zendegi. Azadi. Woman, Life, Freedom. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.womanlifefreedom.today/. ↵

- Mehan, Asma. “Digital Feminist Placemaking: The Case of the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ Movement.” Urban Planning 9 (2024): 8, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.7093. ↵

- Mehan, Asma. “Digital Feminist Placemaking: The Case of the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ Movement.” Urban Planning 9 (2024): 9, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.7093. ↵

- Mehan, Asma. “Digital Feminist Placemaking: The Case of the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ Movement.” Urban Planning 9 (2024): 9, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.7093. ↵

- Mehan, Asma. “Digital Feminist Placemaking: The Case of the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ Movement.” Urban Planning 9 (2024): 8, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.7093. ↵

- Feldman, Ella. “Iranian Artists Stage Anonymous Protest at the Guggenheim Museum.” Smithsonian.com, October 25, 2022. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/red-banners-with-mahsa-aminis-face-cover-the-guggenheim-spiral-in-anonymous-protest-action-180981003/. ↵

- Cascone, Sarah. “Activists Unfurled Red Banners in SFMOMA’s Atrium to Urge the Art World to Support Iran’s Women-Led Protests.” Artnet News, December 1, 2022. https://news.artnet.com/art-world-archives/sf-moma-iran-protest-2214392. ↵

- George, Rachel. “The AI Assault on Women: What Iran’s Tech Enabled Morality Laws Indicate for Women’s Rights Movements.” Council on Foreign Relations, December 7, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/blog/ai-assault-women-what-irans-tech-enabled-morality-laws-indicate-womens-rights-movements. ↵

- Gozzi, David Gritten and Laura. “Iran’s Morality Police to Resume Headscarf Patrols.” BBC News, July 17, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-66218318. ↵

- George, Rachel. “The AI Assault on Women: What Iran’s Tech Enabled Morality Laws Indicate for Women’s Rights Movements.” Council on Foreign Relations, December 7, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/blog/ai-assault-women-what-irans-tech-enabled-morality-laws-indicate-womens-rights-movements. ↵

- Babbs, Verity. “How Is Artificial Intelligence Changing Art History?” Hyperallergic, February 7, 2023. https://hyperallergic.com/781592/how-is-artificial-intelligence-changing-art-history/. ↵

- Aljazeera. “Iranian Singer ‘sentenced to Jail’ over Mahsa Amini Protest Anthem.” Al Jazeera, March 2, 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/3/2/iranian-singer-sentenced-to-jail-over-mahsa-amini-protest-anthem. ↵

- Aljazeera. “Iranian Singer ‘sentenced to Jail’ over Mahsa Amini Protest Anthem.” Al Jazeera, March 2, 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/3/2/iranian-singer-sentenced-to-jail-over-mahsa-amini-protest-anthem. ↵

- Aljazeera. “Iranian Singer ‘sentenced to Jail’ over Mahsa Amini Protest Anthem.” Al Jazeera, March 2, 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/3/2/iranian-singer-sentenced-to-jail-over-mahsa-amini-protest-anthem. ↵

- CBC Radio, “In 1979, Iranian Women Protested Mandatory Veiling - Setting the Stage for Today | CBC Radio.” CBCnews, October 5, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/iran-women-protests-1979-revolution-1.6605982. ↵

- CBC Radio, “In 1979, Iranian Women Protested Mandatory Veiling - Setting the Stage for Today | CBC Radio.” CBCnews, October 5, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/iran-women-protests-1979-revolution-1.6605982. ↵

- CBC Radio, “In 1979, Iranian Women Protested Mandatory Veiling - Setting the Stage for Today | CBC Radio.” CBCnews, October 5, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/iran-women-protests-1979-revolution-1.6605982. ↵

- CBC Radio, “In 1979, Iranian Women Protested Mandatory Veiling - Setting the Stage for Today | CBC Radio.” CBCnews, October 5, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/iran-women-protests-1979-revolution-1.6605982. ↵

- Ghorbani, Pouya. “Iran Protests: Victims Shot in Eyes Hold on to Hopes.” BBC News, April 4, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-64503873. ↵

- Tizhoosh, Nahayat. “Close to 1,000 Iranian Schoolgirls Poisoned in Wave of Attacks, Human Rights Groups Say | CBC News.” CBCnews, November 7, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/iran-schoolgirl-poison-attacks-1.6764821. ↵

- Amnesty . “Iran: Draconian Campaign to Enforce Compulsory Veiling Laws through Surveillance and Mass Car Confiscations .” Amnesty International, March 6, 2024. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/03/iran-draconian-campaign-to-enforce-compulsory-veiling-laws-through-surveillance-and-mass-car-confiscations/. ↵

- Amnesty. “Iran’s Compulsory Veiling Bill a Despicable Assault on Rights of Women and Girls.” Amnesty International, September 21, 2023. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/09/iran-compulsory-veiling-bill-a-despicable-assault-on-rights-of-women-and-girls/. ↵

- “‘A Modern Woman Is Not Only a Housewife and a Mother. the Modern Woman Has Her Own Voice’. Conversation with Oksana Repka in Ukraine.” United Nations, November 19, 2021. https://ukraine.un.org/en/159284-modern-woman-not-only-housewife-and-mother-modern-woman-has-her-own-voice%E2%80%9D-conversation. ↵

- Lajer-Burcharth, Ewa. “Modernity and the Condition of Disguise: Manet’s ‘Absinthe Drinker.’” Art Journal 45, no. 1 (1985): 18–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/776871. ↵

- “Byzantine or Crusader: Icon of the Virgin and Child, Hodegetria Variant: Byzantine or Crusader.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/831188. ↵

- “Byzantine or Crusader: Icon of the Virgin and Child, Hodegetria Variant: Byzantine or Crusader.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/831188. ↵

- “Henri Matisse. Blue Nude II. 1952 | Moma.” MoMA. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/6/316. ↵

- Ghorbani, Pouya. “Iran Protests: Victims Shot in Eyes Hold on to Hopes.” BBC News, April 4, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-64503873. ↵

- Ghorbani, Pouya. “Iran Protests: Victims Shot in Eyes Hold on to Hopes.” BBC News, April 4, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-64503873. ↵

- Ghorbani, Pouya. “Iran Protests: Victims Shot in Eyes Hold on to Hopes.” BBC News, April 4, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-64503873. ↵

- Roose, Kevin. “Can This a.i.-Powered Search Engine Replace Google? It Has for Me.” The New York Times, February 1, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/01/technology/perplexity-search-ai-google.html. ↵

- Leavy, Susan. “Gender Bias in Artificial Intelligence: The Need for Diversity and Gender Theory in Machine Learning.” In GE ’18: Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Gender Equality in Software Engineering, 14. ACM, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1145/3195570.3195580. ↵

- Leavy, Susan. “Gender Bias in Artificial Intelligence: The Need for Diversity and Gender Theory in Machine Learning.” In GE ’18: Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Gender Equality in Software Engineering, 16. ACM, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1145/3195570.3195580. ↵

- Ghorbani, Pouya. “Iran Protests: Victims Shot in Eyes Hold on to Hopes.” BBC News, April 4, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-64503873. ↵