Reconstruction

Akot Kuvonda

Abstract

This project intends to explore the possibility of using AI technologies like Dall-E in ChatGPT to digitally repatriate stolen artworks to Africa, thereby challenging Eurocentric narratives and honouring the continent’s rich cultural heritage. Using a sociological approach, the research will critically evaluate the benefits and drawbacks of using AI in this reconstruction process, including ethical issues like copyright concerns, the accuracy of digital reproductions, and possible effects on cultural authenticity and ownership. While noting the challenges associated with digitally recovering stolen artifacts, this analysis seeks to improve understanding of the role AI may play in protecting and honouring cultural heritage.

In the context of Benin’s royal shrines, the bowls depicted in the image could be associated with calabashes. To better understand what a calabash is, Peju Layiwola defines it as “a hollow, dry, hard shell or cuticle of a plant species known as Lagenaria siceraria, which comes in different sizes and belongs to a larger family known as Cucurbitaceae.”[5] According to Layiwola, calabashes, used since the 9th century A.D. in Igbo-Ukwu, Nigeria, served as ritual vessels and were intricately designed for both functional and artistic purposes.[6] She elaborates that in Yorubaland, the calabash is not just a simple container; it plays a crucial role in royal ceremonies.[7] For example, when a new king is about to be enthroned, he must eat or drink from the calabash.[8] She asserts that this act means he agrees to follow the rules and responsibilities of his position.[9] Thus, the calabash is much more than a vessel; it acts almost like a scepter, a symbol of power and authority used by kings.[10]

*(I have emailed the museum for permission to use their photographs in this publication; fingers crossed, they say yes!!)

To further elaborate, Salome Kiwara-Wilson wrote that in Benin, chiefs were important political figures appointed by the Oba and did not inherit their positions.[14] By the late 1600s, chiefs in Benin, especially the war chief, gained significant power. Their approval became necessary for appointing a new Oba, increasing their influence in military matters, as Wilson states.[15] The 15th century marked Benin's golden age, renowned for creating the Benin bronzes, reflecting the kingdom's prosperity and artistic achievements.[16] Wilson writes that first contact with Europe occurred in the 16th century when Portuguese explorers arrived, leading to a beneficial trade relationship that shifted Benin’s focus to coastal trade.[17] The Portuguese maintained trade routes for centuries, but as they withdrew, other Europeans, particularly the British, sought to dominate and eventually control the region after the Berlin Conference.[18] As British influence expanded, they removed local rulers, leaving Benin as one of the last strongholds, which made the Oba anticipate a similar fate.[19] In 1892, the British attempted to diminish the Oba's power through a treaty that restricted his sovereignty, which the Oba did not fully understand due to his previous experiences with European traders, as per Wilson.[20] Despite an existing treaty, trade issues persisted, leading to new British plans under Ralph Moor and James Phillips to forcefully adjust Benin’s governance to enhance control.[21] Phillips planned an unarmed visit that would challenge the Oba's position; his refusal or acceptance would escalate to British intervention.[22] Phillips' expedition faced skepticism and coincided with the sacred Ague festival, prompting the Oba to attempt to postpone conflict, but Phillips persisted, escalating tensions.[23] The British party was ambushed, leading to quick plans for retaliation by the British, who demanded the return of prisoners and property, intensifying the conflict.[24] The British, after capturing Benin City, looted the palace, taking significant cultural artifacts and initially misattributing their craftsmanship to the Portuguese due to their quality.[25] A fire destroyed much of Benin City days after its occupation, and the deposed Oba later surrendered, was tried for the Phillips massacre, and was exiled instead of executed, Wilson notes.[26] Upon the Oba's death in 1914, his eldest son successfully petitioned the British to restore the monarchy, leading to his crowning as Oba Eweka II.[27] The monarchy transitioned to council-led governance under continued British oversight until Nigerian independence.[28] Despite this, the monarchy persists, and there have been ongoing, albeit unsuccessful, efforts by the Nigerian government and the Benin royal family to reclaim cultural artifacts looted by the British.[29]

Unfortunately, this non-stop begging for cultural artifacts to be returned persists to this day. For instance, ss per Sadiya Chowdhury from Sky News, Nigeria has renewed its demand for the return of the Benin Bronzes after the theft of gold jewelry and semi-precious stone gems from a collection from the British Museum that was later sold on eBay.[30] Abba Isa Tijani, Director of Nigeria's National Commission for Museums and Monuments, criticized the museum's security measures and reiterated that the bronzes, taken in an 1897 invasion, are stolen and should also be returned.[31] Chodwdhury states that the formal requests will be made to the British Museum and government by Nigeria's newly appointed minister of arts, culture, and creative economy.[32] Of course, this cycle of begging will persist until further notice and will eventually be ignored like usual.

The motivations behind choosing this research idea.

Initially, what pulled me towards the idea of repatriating stolen artworks using AI was the lack of representation of African art in my academic experience and, most troublingly, the artwork of Pablo Picasso known as Les Demoiselles Davignon. The conversation surrounding the looted artifacts, which should have been prevalent in educational systems and media across Africa, was virtually nonexistent in public discourse. I find it hilarious in a "crying on the inside kind of way" that this important historical event was played as the game of hide-and-seek in my own African school curriculum. The limitation of discussions on significant issues, like the theft of African cultural heritage, to paid channels highlights the lasting effects of colonization and capitalism's role in hiding important parts of our history. During my university years, the realization that African art has been both underrepresented and misrepresented in the Western world was not merely an academic revelation; it felt like a personal humiliation, challenging not only my understanding of art but also my place within its narratives.

The exploration of Picasso's use of African masks in "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" delves into the complex dynamics between artistic expression and cultural identity representation. This discussion, enriched by Joan Didion's insights on narrative's power, reveals how stories can both illuminate and obscure truths. [38] Didion's analysis highlights the selective storytelling in Picasso's portrayal of African masks, shedding light on the broader issue of cultural appropriation and the sanitization of colonial violence in art histories.

This critical lens is crucial when considering the narratives around stolen artifacts and their portrayal as acts of preservation by colonial powers. Reexamining these stories, possibly with AI's help in reconstructing narratives, can expose the underlying power imbalances and injustices, some might say!! But the main question should be, Can artificial intelligence "really" assist in repairing Africa's historical narrative? Therefore, to answer this question, I personally wanted to navigate the politically charged issue of art repatriation through the use of artificial intelligence to rewrite the sad history of misappropriated African artifacts. If this were to work, the simple act of virtual restoration could carry with it a glimmer of hope for countries that have faced the same story of looted artifacts. It could symbolize a step towards cultural sovereignty and the recognition of our artistic heritage. Moreover, this process of digital reclamation could enable us to shift the narrative by generating artwork grounded in our intrinsic understanding of these pieces rather than allowing them to be misinterpreted or dismissed as primitive simply due to their non-Western origins.

Results

In delving into the blend of technology and cultural restitution, assessing both the benefits and challenges of employing AI for this initiative was imperative. Given the ongoing political sensitivity of this subject, it is clear that while there are advantages to utilizing AI, the disadvantages ultimately overshadow them. Starting with the good experience I had when using AI to generate my image, the hyper-realism produced by the AI images was particularly striking. Additionally, the opportunity to engage in discussions and debates with the software, especially when it generated images that did not align with my requests, was invaluable. This interaction almost mirrored a human conversation, allowing me to assert control over the narrative I sought to convey. It felt empowering to navigate these discussions, as if my voice was finally gaining the recognition it deserved. Moving on to the challenges and limitations it may bring. Given the vast amount of data it takes to reconstruct images or artworks, there is a significant concern about the accuracy of AI-generated reconstructions, which constantly appeared during the process of generating my desired image.

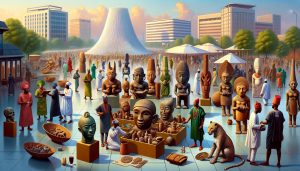

Using the prompt "Generate all the stolen arts I mentioned at the beginning and place them in modern Benin City, being utilized for their traditional and religious purposes," Dalle produced the image on the right (Figure 4). An intriguing observation about Dalle is its habit of restating the initial prompt, seemingly to confirm it has followed the request. Yet, surprisingly, it often presents an image starkly different from the detailed description provided. For instance, Dall-e restated the prompt I gave it: "A scene in modern Benin City where all the previously mentioned stolen artworks are being actively used for their original purposes." However, the scene depicted hardly matches expectations of a religious or traditional ceremony. Instead, it shows individuals engaged in casual conversations, some distracted, some engaged in what could appear as an open market, given the placement of the artworks. Others are walking away from the artworks, indicating a noticeable disconnect between the vibrant communal engagement one would anticipate in such settings and the actual interaction with the artworks. This discrepancy points to a certain detachment from the artworks and the collective religious or traditional activities they are meant to inspire. The second point that caught my attention was Dalle's preference for generating images of modern cities with a Western lens rather than reflecting the African context of a modern city. Through the various prompts I put down for "modern Benin City," Dalle generated images that mostly resembled western countries like Canada. This tendency points to a dataset predominantly shaped by Eurocentric narratives. To get a depiction that more closely resembled the contemporary look of Benin City, I had to refine my prompt to "How about in a regular African Benin City in Nigeria?" The need to specify "regular" over "modern" to obtain an accurate portrayal underscores a larger issue of how African countries are often perceived. It reveals that Dalle's perspective is limited and does not fully encompass the varied experiences and views of life around the world.

This then echoes Emile Durkheim’s theory on the societal shift from collectivism to individualism. Durkheim argued that pre-modern societies are characterized by a collective consciousness where social cohesion comes from shared beliefs and practices.[39] In contrast, modern societies are marked by individualism, where cohesion is based on the specialized roles individuals play in a complex division of labor.

Moreover, the difficulty AI has in accurately capturing the essence of a "modern" African city, defaulting instead to Western-centric interpretations, further illustrates Durkheim's concept. It suggests that modernity, as understood and represented through AI, is often seen through the lens of individualistic, Western narratives, overlooking the collective cultural heritage and identities of non-Western societies.

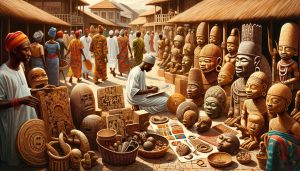

Another interesting theme that kept occurring was the idea of people selling art. Dissatisfied with Figure 4 due to its evident biases, I prompted Dalle once more, specifying, "Try again, but this time focus on religious and traditional practices." True to its usual method, Dalle restated my instructions, reassuringly naming the new generated image (Figure 5) as "a refined scene in Benin City, Nigeria, focusing exclusively on the religious and traditional practices involving the Benin Bronzes." From the image, we can see a sense of commerce taking place based on several visual cues. There are numerous artworks displayed prominently, much like in a market setting where items for sale are often presented to attract buyers. Additionally, the presence of the individual examining the artworks closely suggests that they might be potential buyers evaluating the pieces before making a purchase. The individual seated and writing could be documenting sales or keeping an inventory—common tasks associated with selling goods. Furthermore, the open, public setting and the layout of the artworks on display are typical of a market or bazaar (an open-air market style that is very well known in Africa), where selling and trading occur. This could be seen as an issue of capitalism, where everything, even objects of sacred or communal value, can be treated as commodities. Instead of being preserved as heritage or used in traditional practices, they are being bought and sold, which can contribute to the erosion of cultural identity and can also imply a form of cultural exploitation.[40] This commercialization often strips items of their intrinsic value and reduces them to mere goods with a price tag, which is a significant concern in discussions about capitalism's impact on culture and history.

Lastly, the dilemma of using AI to replicate artworks, which raises ethical concerns over copyright and the integrity of historical records, mirrors larger systemic issues in technology's relationship with society. For instance, while copyright laws restrict alterations to Picasso's protected works, the ease with which AI can mimic artifacts like the Benin Bronze Head is surprising. This leads to the realization that these stolen artworks lacked copyright protection, mainly because they were appropriated without any recognition of their original artists. This therefore spotlights a Eurocentric bias in the preservation and recognition of Africa's cultural heritage.

Conclusion

Exploring this from a sociological angle invites us to critique the diverse makeup of the people that create these new technologies, societal norms, and the power dynamics at play, all of which can subtly influence our narratives in this world. So, dear reader, I hope you get to ask the same questions I ask: Who are the creators behind the technology we daily rely on? How do these teams navigate the challenge of ensuring that their personal and institutional biases do not seep into the AI systems, especially ones like ChatGPT that have captured global attention?

As a student at the University of Ottawa studying sociology and art history, Akot Kuvonda is very interested in the complex relationships that exist between the social meanings of art and its expressive potential. Her academic path is devoted to comprehending how art may influence and reflect cultural and social identities. This investigation is driven by a variety of initiatives and interactions that she has participated in while attending her studies at the University of Ottawa as well as within her personal life. In order to connect the theoretical with the practical, she is continuously looking for ways to apply her insights to real-world situations as she progresses through her dual degree program.

- Dall-e, a tool for generating digital images from textual descriptions, is accessible through ChatGPT, a platform developed by OpenAI. ↵

- Jean Baudrillard, "Simulacra and Simulations (1981)." In Crime and Media (N.P.: Routledge, 2010), 69–70. Baudrillard refers to this as an image or representation that replaces reality with its own simulation. ↵

- Authors: Emma George Ross, “Benin Chronology | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History,” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, accessed May 11, 2024, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bnch/hd_bnch.htm. ↵

- Ross, “Benin Chronology | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.” ↵

- Peju Layiwola, “Calabashes as Receptacles of Traditional Medicine and Repositories of Culture amongst the Yoruba People of South-West Nigeria,” A Textbook of Medicinal Plants from Nigeria, 2008, 81–92. ↵

- Layiwola, “Calabashes as Receptacles of Traditional Medicine and Repositories of Culture amongst the Yoruba People of South-West Nigeria.” ↵

- Layiwola, “Calabashes as Receptacles of Traditional Medicine and Repositories of Culture amongst the Yoruba People of South-West Nigeria.” ↵

- Layiwola, “Calabashes as Receptacles of Traditional Medicine and Repositories of Culture amongst the Yoruba People of South-West Nigeria.” ↵

- Layiwola, “Calabashes as Receptacles of Traditional Medicine and Repositories of Culture amongst the Yoruba People of South-West Nigeria.” ↵

- Layiwola, “Calabashes as Receptacles of Traditional Medicine and Repositories of Culture amongst the Yoruba People of South-West Nigeria.” ↵

- “Trompe l’oeil,” March 27, 2024, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/trompe-l-oeil. “A painting that is cleverly designed to trick people into thinking that the objects represented in it are really there.” ↵

- G. A. AKINOLA, “THE ORIGIN OF THE EWEKA DYNASTY OF BENIN: A STUDY IN THE USE AND ABUSE OF ORAL TRADITIONS,” Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 8, no. 3 (1976): 21–36.[/footnote] The first king, Igodo, started a line that lasted through 31 kings, as Egharevba mentions. He goes on to state that the last king, Owodo, was removed because of his harsh rule. His son, prince Ekaladerhan, also known as Oduduwa, who was supposed to take over the throne but was long exiled before, refused to return even after his father was banished. During the time of his exile, it is claimed that he ended up as a prince in Ife (currently known as Osun State in Nigeria).[footnote] G. A. AKINOLA, “THE ORIGIN OF THE EWEKA DYNASTY OF BENIN: A STUDY IN THE USE AND ABUSE OF ORAL TRADITIONS,” Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 8, no. 3 (1976): 21–36.[/footnote] The people then tried a republican form of government led by a commoner, Evian. [footnote] AKINOLA, “THE ORIGIN OF THE EWEKA DYNASTY OF BENIN: A STUDY IN THE USE AND ABUSE OF ORAL TRADITIONS.” ↵

- AKINOLA, “THE ORIGIN OF THE EWEKA DYNASTY OF BENIN: A STUDY IN THE USE AND ABUSE OF ORAL TRADITIONS.”[/footnote] This led to Oranmiyan's, the son of the exiled prince Ekaladerhan, arrival in Benin City. Eventually, during Oranmiyan's time in Benin, he married an Edo woman by the name of Erinwinde, to whom they bore a son, Eweka 1, becoming the first ever Oba, starting a new dynasty that faced little opposition, along with many other dynasties as time went on.[footnote]AKINOLA, “THE ORIGIN OF THE EWEKA DYNASTY OF BENIN: A STUDY IN THE USE AND ABUSE OF ORAL TRADITIONS.” ↵

- Salome Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories,” DePaul J. Art Tech. & Intell. Prop. L 23 (2012): 375. ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Kiwara-Wilson, “Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories.” ↵

- Sadiya Chowdhury, “Nigeria Demands Return of Benin Bronzes after Thefts from British Museum,” Sky News, accessed May 12, 2024, https://news.sky.com/story/nigeria-demands-return-of-benin-bronzes-after-thefts-from-british-museum-12946236. ↵

- Chowdhury, “Nigeria Demands Return of Benin Bronzes after Thefts from British Museum.” ↵

- Chowdhury, “Nigeria Demands Return of Benin Bronzes after Thefts from British Museum.” ↵

- William Rubin, From Narrative to ‘Iconic’ in Picasso: The Buried Allegory in Bread and Fruitdish on a Table and the Role of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Art Bulletin, 1983), 630. ↵

- Rubin, From Narrative to ‘Iconic’ in Picasso: The Buried Allegory in Bread and Fruitdish on a Table and the Role of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 631-632. ↵

- Rubin, From Narrative to ‘Iconic’ in Picasso: The Buried Allegory in Bread and Fruitdish on a Table and the Role of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 631-632 ↵

- Rubin, From Narrative to ‘Iconic’ in Picasso: The Buried Allegory in Bread and Fruitdish on a Table and the Role of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 631-632 ↵

- Rubin, From Narrative to ‘Iconic’ in Picasso: The Buried Allegory in Bread and Fruitdish on a Table and the Role of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 631-632. ↵

- Joan Didion, The White Album Essay (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2009), 8–9. Didion discusses the impact of narratives on our understanding of history and culture, offering a lens through which to assess how narratives can shape reality. ↵

- Charles E. Marske, “Durkheim’s ‘Cult of the Individual’ and the Moral Reconstitution of Society,” Sociological Theory 5, no. 1 (1987): 1–14, https://doi.org/10.2307/201987. For further explanation, Marske explains that Durkheim challenged the idea that collective morality diminishes in modern societies, suggesting instead that societal evolution from traditional to modern forms does not eliminate moral obligations but transforms them into a new type of collective morality known as organic solidarity. In modern societies, according to Durkheim, the principle of individualism becomes the core of moral unity, which he saw as the true form of individualism and the ultimate basis of modern society's moral fabric ( Marske, 1987, 2). ↵

- Hüseyin Özel, “COMMODIFICATION,” in Karl Polanyi’s Political and Economic Thought, ed. Gareth Dale, Christopher Holmes, and Maria Markantonatou, A Critical Guide (Agenda Publishing, 2019), 131–50, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvnjbfgk.11. Hüseyin Özel examines how every human trait and aspect is turned into abstract units for the market system. He agrees with Polanyi, Marx, and Lukács that this reflects a continuous process of market expansion into all areas of life, aiming to commodify everything, including fundamental human experiences like family and science. (Özel, 2019, 131). ↵

- Martha J. Cutter, “Editor’s Introduction: The Haunting and the Haunted,” MELUS 37, no. 3 (2012): 5–12. In the Introduction of this article, Martha J. Cutter cites Avery Gordon direct quote Gordon. In other words Cutter references Avery Gordon, explaining how hauntings disrupt our sense of time by making specters visible when unresolved issues surface. Gordon states, "The ghost... has a real presence and demands its due, your attention," emphasizing that ghosts signify tangible presences that require acknowledgment. ↵