5

Section one: The fundamentals

A)

Exercise 1: Notebook Prompt

Many of you are likely familiar with the concept of “ability inequity,” which the authors of this article define as “an unjust or unfair (a) ‘distribution of access to and protection from abilities generated through human interventions’ or (b) ‘judgment of abilities intrinsic to biological structures such as the human body’.”

However, they go on to identify the following “ability concepts” that are less familiar:

1) ability security (one is able to live a decent life with whatever set of abilities one has)

2) ability identity security (to be able to be at ease with ones abilities)

How prevalent are these forms of security among disabled people you know? Or, if you identify as a disabled person, would you say your social surroundings and community foster and support these kinds of security? Furthermore, while the focus of the article is on Kinesiology programs, it is also important to reflect on how academia in general accommodates for disability. If you feel comfortable answering this question, what has been your experience of postsecondary education to date?

-OR-

The authors also observe that “Ableism not only intersects with other forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, ageism, and classism, but abilities are often used to justify such negative ‘isms’.”

What do you think this means? Provide an example.

| The second prompt suggests that societal ideas about ability are often used to justify discrimination in other areas. For example, sexism has been reinforced by arguments about women’s supposed physical or emotional “weakness,” limiting their access to education, employment, and leadership roles. One concrete example is the intersection of ableism and classism in the workforce. Many jobs require a certain level of physical ability, and workplaces often fail to accommodate disabled employees. This lack of accessibility can reinforce economic inequality, as disabled people may struggle to find stable employment, making them more vulnerable to poverty. In this way, ableism upholds classism by maintaining barriers to economic participation.

|

Exercise 2: Implicit Bias Test

Did anything surprise you about the results of the test? Please share if you’re comfortable OR comment on the usefulness of these kinds of tests more generally.

| I was surprised by my results, as I found the test itself to be quite controversial and ableist. The shifting key placements between rounds seemed designed to confuse users and increase the likelihood of mistakes. Additionally, the final round, which associated able-bodied images with “good” words and disabled body images with “bad” words, felt particularly problematic. My results indicated a 37% preference for able-bodied individuals over disabled individuals, but I’m unsure how these conclusions were reached. I reject these results, as I consider myself extremely open-minded and not someone who judges others based on their physical abilities. I believe the test’s design may have influenced the outcome rather than accurately reflecting my true attitudes toward disabled individuals. I did not find this test useful as the IAT assumes that reaction times in word-association tasks accurately reflect deep-seated biases, but critics argue that these split-second responses don’t necessarily translate into real-world behavior. It also emphasizes personal biases without acknowledging that the images used in the test are inherently biased themselves, as they portray disability solely as a physical condition. Additionally, at the beginning of the test, I had to put in my race, gender, age and I can’t help but wonder if these had something to do with my results.

|

B) Keywords

Exercise 3:

Add the keyword you contributed to padlet and briefly (50 words max) explain its importance to you.

| The Medical Model of disability frames the disabled body as the problem, emphasizing that disability is something that needs to be “fixed” or “cured.” This perspective places responsibility solely on the individual, viewing disability through a lens of impairment and limitation. Terms such as “confined to a wheelchair” or “housebound” reinforce this notion by implying that disabled individuals are restricted or trapped by their condition.

|

B) On Disability

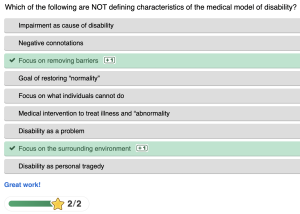

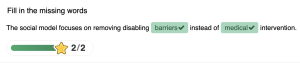

Exercise 4: Complete the Activities

Exercise 5: Notebook Prompt

What do Fitzgerald and Long identify as barriers to inclusion and how might these apply to sport in particular?

Fitzgerald and Long identify barriers for disabled people that stem from a perspective that assumes they are inherently incapable of participating in various activities due to their disability. This view leads to their exclusion, not because of an actual inability, but because society fails to recognize or accommodate the diverse abilities of disabled individuals. By viewing disability as a deficiency or limitation, this perspective reinforces the idea that disabled people are less capable and should be excluded from certain activities, whether in education, the workplace, or social environments. It shifts the responsibility from the individual to society, emphasizing the need for accessibility, inclusion, and a more open-minded view of ability.

C) Inclusion, Integration, Separation

Exercise 6: Complete the Activities

Exercise 7: Notebook Prompt

Choose ONE of the three questions Fitzgerald and Long argue disability sport needs to address and record your thoughts in your Notebook.

- Should sport be grouped by ability or disability?

- Is sport for participation or competition?

- Should sport competitions be integrated?

| Fitzgerald and Long’s question about whether sport is for participation or competition touches on a deeper debate regarding the purpose of sport, particularly in the context of disability. On one hand, sport can be an avenue for competition, pushing individuals to excel, set records, and demonstrate peak physical performance. On the other hand, participation in sport should not be overlooked as a fundamental aspect of its value, especially in the context of disability. For many disabled individuals, sport is not just about competing but about inclusion, physical well-being, personal growth, and social engagement. Participation allows athletes to experience the benefits of physical activity, build confidence, and be part of a community, regardless of their performance level. In the case of disability sport, the distinction between participation and competition is especially important. Some disabled athletes may be more focused on participation for the sake of health and inclusion, while others may strive for competitive success. The key is to recognize that both aspects are valuable and should coexist. I believe sport should serve both purposes, participation and competition. It is essential to provide spaces where people can engage in sport according to their abilities and goals, ensuring that the sport experience is enriching for all.

|

Part Two: Making Connections

A) Gender, Sport and Disability

Exercise 8: Complete the Activity

The paradox that sportswomen habitually face (as the authors observe, this isn’t confined to disabled sportswomen) involves the expectation they will be successful in a ‘masculine’ environment while complying with femininity norms in order to be recognized as a woman.

True or false?

Take a moment to reflect on this paradox below (optional).

|

Sports Women often navigate a paradox in which they are expected to succeed in a domain traditionally associated with masculinity, characterized by traits like aggression, strength, and competitiveness, while simultaneously adhering to societal norms of femininity to be recognized and accepted as women. This topic reminds me of the Nike “Dream Crazier” commercial where women are constantly reprimanded for showing emotion, dreaming of equal opportunity, being ‘too good’, or standing up for something. While male athletes are typically celebrated for their physical prowess and competitiveness, female athletes often experience pressure to balance their athletic identity with conventional femininity, whether through their attire, behavior, or public image. This paradox is particularly relevant in the media where headlines will be about a female athlete’s clothes instead of her win. As a female athlete myself, I deeply understand this struggle. Throughout my life, I’ve been told that my sports were never as important as those of my male peers or questioned for getting upset, hearing dismissive remarks like, “It’s just a girls’ soccer game.” The double standard in women’s sports is something that will always stay with me because it shaped the narrative I grew up in. I think this is why this topic is so important to me, and why I continue fighting for women’s sports.

|

B) Masculinity, Disability, and Murderball

Exercise 9: Notebook/Padlet Prompt

Watch the film, Murderball and respond to the question in the padlet below (you will have an opportunity to return to the film at the end of this module).

The authors of “Cripping Sport and Physical Activity: An Intersectional Approach to Gender and Disability” observe that the “gendered performance of the wheelchair rugby players can…be interpreted as a form of resistance to marginalized masculinity” (332) but also point out that it may reinforce “ableist norms of masculinity.” After viewing the film, which argument do you agree with?

a) Murderball celebrates a kind of resistance to marginalized masculinity

| After watching Murderball, I would argue that the film both resists and reinforces marginalized masculinity. On one hand, it challenges stereotypes by demonstrating that men with disabilities can embody traditionally masculine traits such as aggression, competitiveness, strength, and resilience. The athletes defy the notion that disabled men are weak or dependent, proving they can be just as tough, driven, and capable as their able-bodied counterparts. Their participation in high-contact wheelchair rugby becomes a form of empowerment, pushing back against societal perceptions that disability inherently diminishes masculinity.

However, Murderball also reinforces ableist norms of masculinity by emphasizing hyper-masculine traits like aggression, dominance, and physical toughness. The film largely equates masculinity with physical power and endurance, potentially marginalizing those who do not fit this mold. In this way, it upholds the idea that to be considered “manly,” even as a disabled athlete, one must conform to traditional, physically demanding ideals of masculinity.

|

Section Three: Taking a Shot

A) Resistance

B) Calling out Supercrip

Exercise 10: Mini Assignment (worth 5% in addition to the module grade)

1) Do you agree with the critique of the “supercrip” narrative in this video? Why or why not? Find an example of the “supercrip” Paralympian in the 2024 Paris Paralympics or Special Olympics coverage and explain how it works.

| I agree with the critique of the “supercrip” narrative in this video, which portrays individuals with disabilities as heroic figures who overcome their impairments, which is extremely harmful. While these stories aim to inspire, they can inadvertently perpetuate harmful stereotypes by setting unrealistic expectations for all disabled individuals and shifting focus away from systemic barriers that need addressing. By labeling these athletes as “supercrips,” it frames their achievements in a way that invites pity and sadness rather than genuine admiration for their skills and dedication. It suggests that their success is remarkable because of their disability, rather than recognizing them as elite athletes in their own right.

An example of the “supercrip” narrative can be seen in the media coverage of French Paralympian Pauline Déroulède during the 2024 Paris Paralympics. After losing her leg in a traffic accident in 2018, Déroulède pursued a career in wheelchair tennis. Media outlets often highlighted her journey as a tale of personal triumph over adversity, focusing on her resilience and determination to return to sports. Instead of seeing Paralympians as inspirational solely because they have a disability, we should acknowledge them as athletes first, just as we do with Olympians. Their training, discipline, and success should be appreciated within the broader context of sport, not just as a feel good story of overcoming adversity. Additionally, by emphasizing personal heroism, the “supercrip” narrative may suggest that the weight is on disabled people to adapt, rather than on society to become more inclusive. This perspective can lead to overlooking the diverse experiences of disabled individuals who may not fit into this narrow framework of “inspirational” success. While stories like Déroulède’s highlight remarkable personal achievements, it’s crucial to approach such narratives critically. Recognizing the potential pitfalls of the “supercrip” trope can lead to more balanced representations that celebrate individual successes without perpetuating limiting stereotypes or ignoring systemic issues.

|

2) Does the film Murderball play into the supercrip narrative in your opinion? How does gender inform supercrip (read this blog for some ideas)?

(300 words for each response)

| In my opinion, Murderball both challenges and reinforces the “supercrip” narrative. The film provides a raw and compelling look into the world of wheelchair rugby, showcasing athletes who refuse to be defined by their disabilities. By emphasizing their athleticism, competitiveness, and physical toughness, Murderball challenges the stereotype that disabled individuals are passive or incapable of intense physical activity. However, in doing so, it also risks reinforcing the “supercrip” narrative by portraying these athletes as inspirational solely because they have “overcome” their impairments.

The blog article highlights how the media often celebrates disabled individuals only when they achieve extraordinary acts, such as walking at graduation or swimming across the San Francisco Bay. This suggests that disabled people must prove themselves through exceptionalities to be deemed worthy of respect. Similarly, Murderball focuses heavily on the athletes’ ability to conform to hyper masculine ideals of strength and aggression, which can be interpreted as reinforcing ableist norms. As the blog notes, the first widely accepted disabled figures in mainstream media were typically rugged, muscular, and white men, fitting into traditional masculine frameworks. The wheelchair rugby players in Murderball align with this image, further perpetuating the idea that disabled people are only celebrated when they reflect able-bodied expectations. Gender plays a significant role in shaping the “supercrip” narrative. As the blog points out, society has historically accepted disabled men who exude toughness and independence, while those who do not fit this mold remain marginalized. When disabled women do achieve or present exceptional athletic ability, they are commonly subjected to additional scrutiny regarding their appearance, femininity, and desirability. This double standard reinforces both ableist and sexist ideals, limiting the range of acceptable identities for disabled individuals in sport and media. Not only does this pressure disabled individuals to present themselves in ways that align with the “normal body”, it also pressures them to align with dominant social ideals rather than embracing diverse forms of identity.

|

3) How does the film model resistance to both disability and gender norms, and in what ways do the athletes redefine or subvert societal expectations of strength, independence, and masculinity?

For Extra credit:

The film Murderball models resistance to both disability and gender norms by showcasing athletes who reject traditional perceptions of disability as weakness and dependence. The wheelchair rugby players embody physical aggression, resilience, and competitiveness, directly challenging stereotypes that disabled individuals are fragile or incapable of high-intensity sports. Through their participation in a full-contact sport, they push back against the medical model of disability, which frames impairment as something to be fixed, instead embracing their bodies as strong and capable within their own terms.

At the same time, the film complicates gender norms by portraying disabled men who redefine masculinity beyond conventional able-bodied ideals. While they emphasize traits such as strength and toughness, their brotherhood and open discussions of vulnerability offer an alternative to rigid, hypermasculine norms. By highlighting the athletes’ relationships, struggles with independence, and self-perceptions, the film suggests that masculinity is not solely based on physical dominance and appearance but also about adaptability, perseverance, and emotional resilience.

However, Murderball also reinforces certain ableist and gendered expectations. The athletes assert their masculinity by aggressively distancing themselves from stereotypes of disabled people as weak or asexual. The film often highlights their sexual relationships and physical prowess as proof of their manhood, which, while empowering, still aligns with conventional notions of masculinity tied to physical strength and sexual success. As well as the film focuses almost exclusively on male athletes, reinforcing the idea that competitive sports are primarily male domains. This exclusion of women in disability sport narratives further marginalizes disabled female athletes, whose experiences of gender and disability remain largely unexamined.