Before it gets to our plates, every food has a story. Maybe it started as a seed, planted in soil and nurtured to maturity with water, sunlight, and fertilizer. Or maybe it came from an animal, one raised for its meat or to produce milk or eggs. We choose foods based on their taste, price, convenience, and nutritional value, but it’s also worth considering their backstories. This is particularly true for protein foods, because animal protein production generally consumes more resources and is less sustainable than plant protein sources. Agricultural animals need care, feeding, housing, disposal of their waste, and sometimes medication use throughout their lives. It’s worth considering where our protein comes from and how our choices affect the planet, especially since most of us consume more protein than we need.

Animal Agriculture and Resource Use

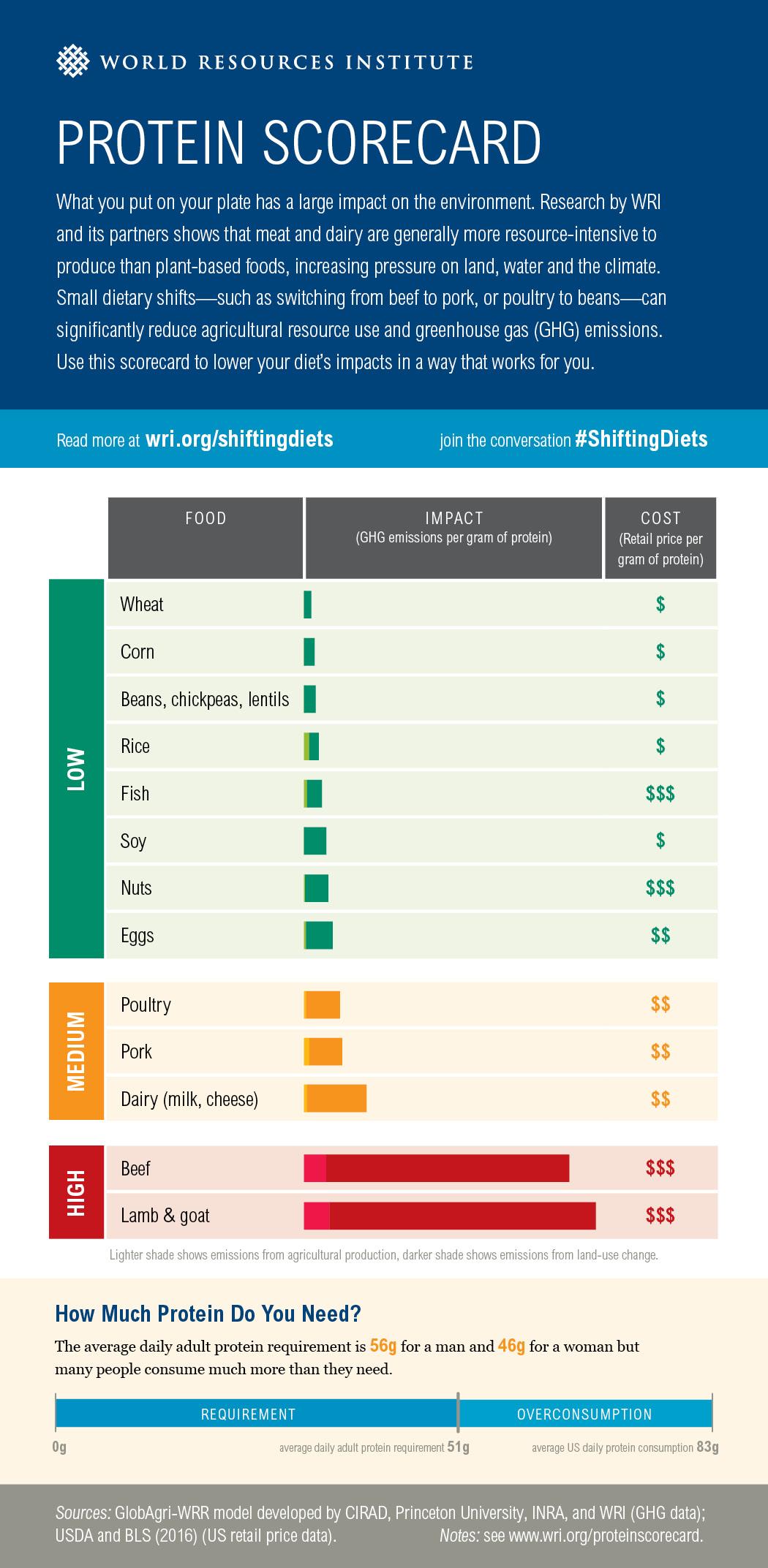

The World Resources Institute, a global research non-profit organization with a mission “to move human society to live in ways that protect Earth’s environment” has compiled data on the environmental impact of protein choices. In the graphic below, you’ll see that in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, protein sources from plants have a much lower impact than protein sources from animals. Most plant proteins, with the exception of nuts, are also less expensive. Beef, lamb, and goat meat come at a higher cost to the environment and your wallet.

Fig. 6.25. Protein Scorecard from the World Resources Institute. Source: https://www.wri.org/resources/data-visualizations/protein-scorecard

Beef is among the most resource-intensive sources of protein. A 2014 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences calculated that beef production uses 28 times more land and 11 times more irrigation water than the average of dairy, poultry, pork, and egg production.1

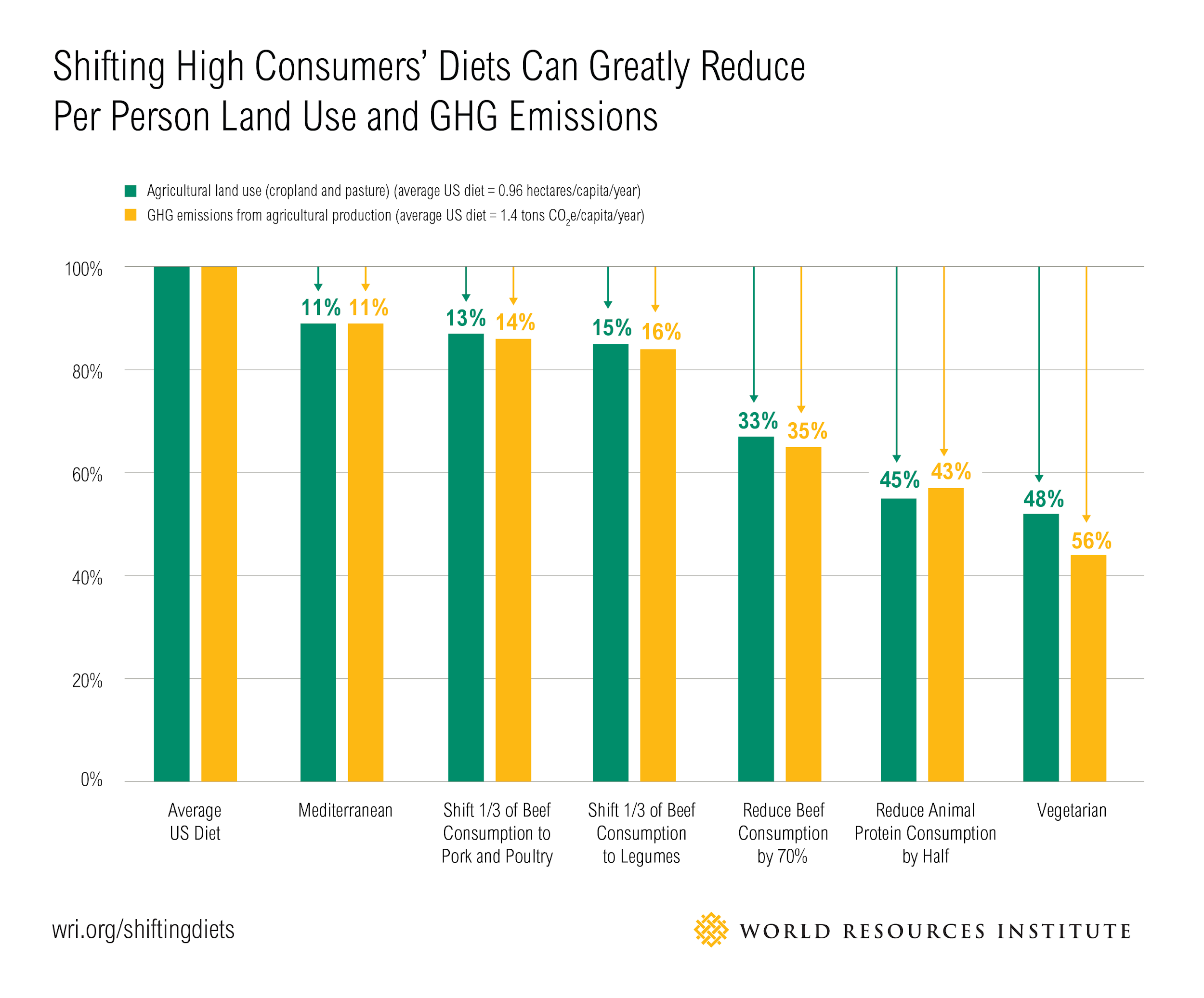

It’s important to point out that sustainable animal agriculture does fill some important roles that plants can’t. For example, much of the world’s pasture land is on steep terrain that wouldn’t work well for growing food crops. And animal waste—in the form of manure—is an important fertilizer, including in organic food systems. So, animal agriculture and eating meat aren’t inherently bad for the environment, but it would probably be good for the planet if we ate less meat, as shown in the graphic below.

Fig. 6.26. Shifting High Consumers’ Diets Can Greatly Reduce Per Person Land Use and GHG Emissions from the World Resources Institute. Source: https://www.wri.org/resources/charts-graphs/animal-based-foods-are-more-resource-intensive-plant-based-foods

In terms of environmental impact, making small shifts can have a significant impact. Consider the following approaches2:

- If you eat meat every day, try adding a “meatless Monday” into your week and experiment with some vegetarian recipes. Once you’ve adapted to that, try adding another day.

- Replace some of your beef meals with dishes featuring chicken, pork, eggs, fish, or legumes.

- Eat smaller portions of meat and add more plant foods to your plate. For example, if you enjoy spaghetti and meat sauce, try using less meat in your sauce and adding in vegetables like mushrooms, bell peppers, and carrots. Your meal will be more nutrient-dense and maybe even more flavorful.

When you consider that moderate shifts like these would not only be good for the planet but also good for our health, then they don’t seem like much of a sacrifice. A 2016 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences concluded that just following standard dietary guidelines (which recommend a variety of protein sources, including plant proteins, and eating more whole grains, fruits and vegetables) could reduce mortality by 6 to 10 percent and cut greenhouse gas emissions by 29 to 70 percent.3,4

This page from the World Resources Institute provides more information: Sustainable Diets: What You Need to Know in 12 Charts, by Janet Ranganathan and Richard Waite, April 20, 2016.

Animal Agriculture and Antibiotic Resistance

One of the biggest current threats to public health is antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics are life-saving drugs, but over time, bacteria can develop resistance to them. This means that the antibiotics no longer work to kill the bacteria causing infections, leaving people with more severe illnesses and fewer treatment options, often needing to try different antibiotics that have more side effects. There are now some bacterial infections for which we have no working antibiotics to treat them. According to the CDC, at least 2.8 million people are infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria each year in the U.S, and these infections are thought to kill at least 35,000 people annually.5 Addressing this problem will require us to be more careful about how we use antibiotics, invest in research to develop new ones, and to develop other ways of preventing bacterial disease, such as new vaccines.

Antibiotics are important to both human and animal medicine. When we’re sick with a bacterial illness, we may need antibiotics to treat it, and the same is true of animals, whether they’re raised for agriculture or part of our families as our pets. The problem is that the more we use antibiotics, the more chances bacteria have to evolve resistance to them, and the less effective those antibiotics become.

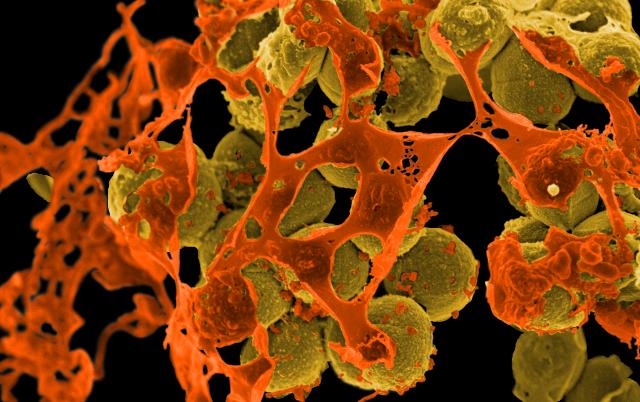

Fig. 6.27. Scanning electron micrograph of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA, brown) surrounded by cellular debris. MRSA resists treatment with many antibiotics. Credit: NIAID

VIDEO: “Watch antibiotic resistance evolve” by Science News, YouTube (September 8, 2016), 2:02 minutes. Watch how quickly bacteria can develop resistance to antibiotics when they’re exposed to them and how resistant populations can grow.

The overuse of antibiotics in both human medicine and animal agriculture has contributed to the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. For example, taking antibiotics for an illness caused by a virus, such as the common cold or the flu, won’t make you better and just gives harmful bacteria chances to evolve resistance. Historically, antibiotics were also routinely given to food production animals to make them fatter, and that allowed for the growth of antibiotic resistance. As of 2017, the FDA ruled that antibiotics can no longer be used for growth promotion in animal agriculture, a significant step in reducing the overuse of these drugs that are important to both humans and animals. Data released by the FDA in December 2018 show that antibiotic sales for farm animals have dropped significantly after this rules change.6

Antibiotics can still be used to treat sick farm animals or stop the spread of disease, which is important for animal health and welfare. However, antibiotics can also be used to prevent disease in animals that might become sick. Many experts argue that allowing antibiotics to be used for disease prevention leaves a loophole for large amounts of antibiotics to continue to be used, especially in farming systems where animals are crowded and diseases can spread quickly. The World Health Organization has called for this practice to stop, reserving antibiotics only for use in animals that are already sick, not healthy animals. The goal is to reduce antibiotic use in order to reduce the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, so that we can still use these valuable medicines to treat sick animals and humans when needed.

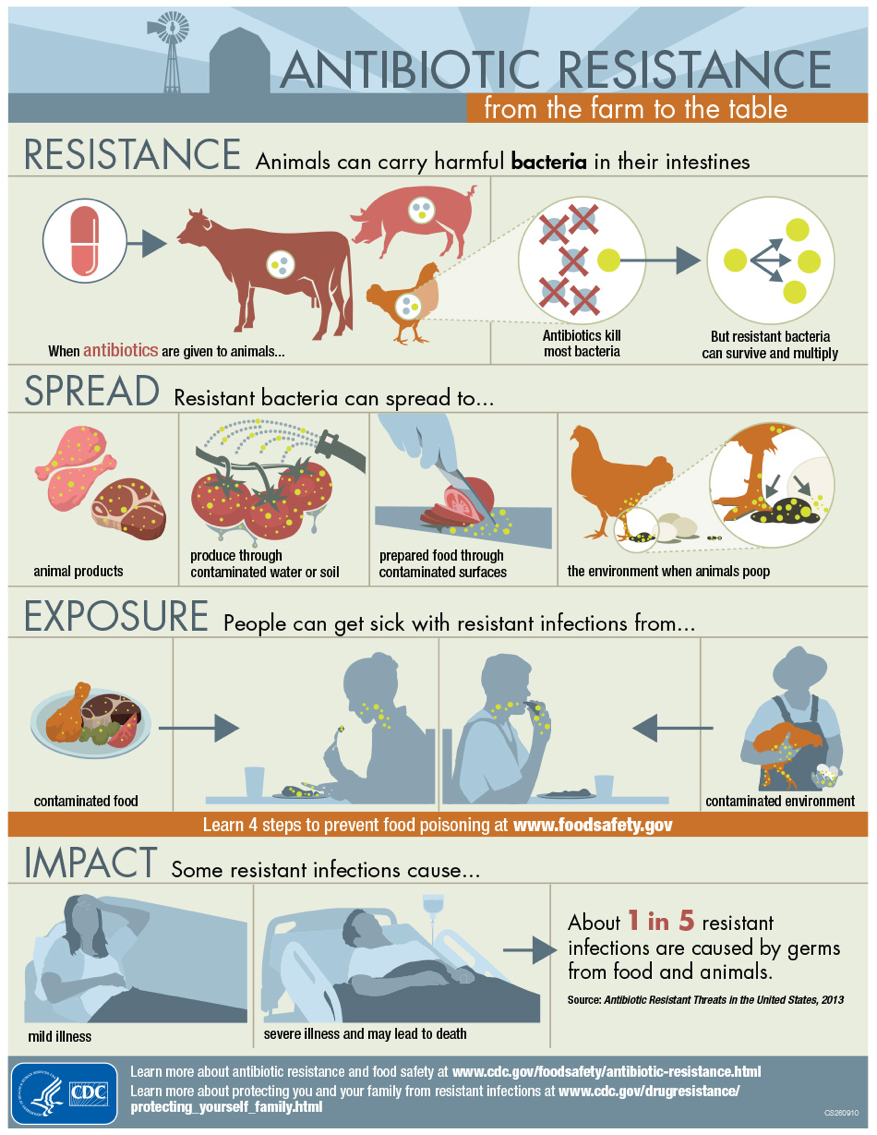

When antibiotics are used in food animals, bacteria can evolve resistance to those antibiotics. Those antibiotics-resistant bacteria can then be present in your meat, and they can spread in the environment from animal feces, including into the water used to irrigate fruits and vegetables. Humans exposed to these bacteria by handling or eating contaminated food can then become sick with infections that are resistant to antibiotic treatment, as shown in this infographic from the CDC:

Fig. 6.28. Antibiotic Resistance from Farm to Table infographic from the CDC. Source: https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/challenges/from-farm-to-table.html

VIDEO: “How industrial farming techniques can breed superbugs,” by PBS NewsHour, YouTube (August 9, 2017), 9:37 minutes. This video explains the link between agriculture and development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

What can you do to prevent yourself and your family from getting sick with antibiotic-resistant infections? The CDC offers these tips, most of which are useful for reducing your risk of foodborne illness in general:

- Take antibiotics only when needed.

- Follow simple Food Safety Tips:

- COOK. Use a food thermometer to ensure that foods are cooked to a safe internal temperature: 145°F for whole beef, pork, lamb, and veal (allowing the meat to rest for 3 minutes before carving or consuming), 160°F for ground meats, and 165°F for all poultry, including ground chicken and turkey.

- CLEAN. Wash your hands after touching raw meat, poultry, and seafood. Also wash your work surfaces, cutting boards, utensils, and grill before and after cooking.

- CHILL. Keep your refrigerator below 40°F and refrigerate foods within 2 hours of cooking (1 hour during the summer heat).

- SEPARATE. Germs from raw meat, poultry, seafood, and eggs can spread to produce and ready-to-eat foods unless you keep them separate. Use different cutting boards to prepare raw meats and any food that will be eaten without cooking.

- Wash your hands after contact with poop, animals, or animal environments.

- Report suspected outbreaks of illness from food to your local health department.

- Review CDC’s Traveler’s Health recommendations when preparing to travel to a foreign country.

When you shop for meat, milk, and eggs, you’ll see lots of different types of labels making claims about how the animals were raised. Does any of this matter when it comes to antibiotic resistance? First, it’s important to note that no animal products—however they’re labeled—should ever contain antibiotics, as required by federal law. If an animal is treated with an antibiotic, it can’t be sold for slaughter or have its milk sold until the antibiotic is cleared from its system. However, if animals were routinely treated with antibiotics earlier in their lives, those practices could have contributed to the growing problem of antibiotic resistance.

Choosing products that are certified organic ensures that antibiotics weren’t used in their production, because organic farms are not allowed to use antibiotics even for sick animals.7 (If an animal becomes sick and requires antibiotic treatment to get better, its milk, meat, or eggs can no longer be sold as organic, but it can be sold to a conventional farm.)

You’ll also see labels stating “raised without antibiotics,” and buying these products helps to support farmers and companies that have committed to reducing antibiotic use in their production systems, even if they aren’t certified organic. However, antibiotic resistant bacteria (bacteria that have evolved resistance to antibiotics so could cause hard-to-treat infections) may still be present in products that are labeled certified organic or “raised without antibiotics” (the bacteria could have spread to these animals from somewhere else), so follow the food safety rules no matter where your meat comes from.8

Figure 6.29. These eggs are certified organic, so you can be confident that antibiotics weren’t used in their production. The sausage is not organic, but it is made from chickens raised without antibiotics, so its production is unlikely to have contributed to the problem of antibiotic resistance.

More and more companies are also recognizing how the overuse of antibiotics can contribute to antibiotic resistance, and they’re changing their practices. In December 2018, a large consortium of companies and industry groups, including Walmart, McDonald’s, and Tyson Foods, committed to a framework for more responsible use of antibiotics.9

Additional reading:

How Drug-Resistant Bacteria Travel from the Farm to Your Table (https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-drug-resistant-bacteria-travel-from-the-farm-to-your-table/)

By Melinda Wenner Moyer, Scientific American, 12/1/16

Issues of Fish Sustainability

Fish are a good source of protein and healthful polyunsaturated fats, as well as micronutrients like vitamin D, so they’re often mentioned as a good choice. From the charts at the top of this page, you can also see that fish are a relatively sustainable source of protein in terms of using little land and freshwater and producing low levels of greenhouse gases.

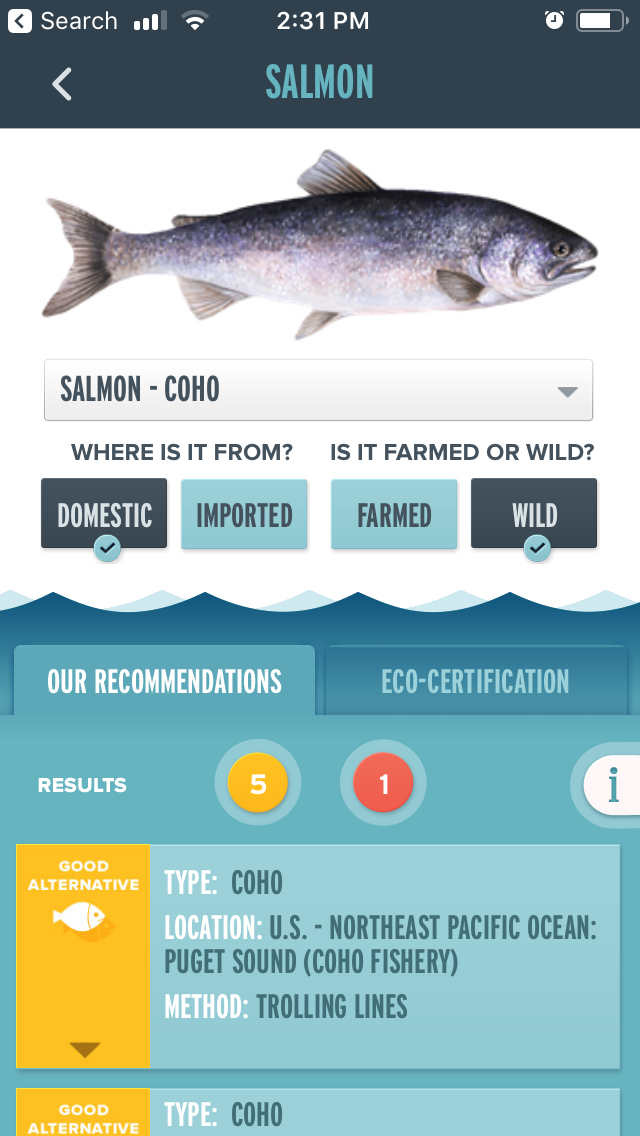

However, the oceans have been overfished, and global supplies of wild-caught fish are dwindling. Aquaculture, or fish farming, has also created new environmental challenges. Both of these issues are being solved with good management, like careful limits on wild-caught fishing and new management practices for fish farming. You can encourage these practices by purchasing sustainably-sourced seafood.10 The Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch program can help with this. You can download their app to help with buying decisions in the grocery store and find more information on their website: Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch.

Fig. 6.30. A screenshot from the Seafood Watch app, showing how it can help you make sense of seafood buying options.

VIDEO: “Can the Oceans Keep Up with the Hunt?” by the Monterey Bay Aquarium, YouTube (July 20, 2012), 15:57 minutes. Learn more about problems with fish sustainability and solutions by watching this video.

You may have also heard that fish can contain dangerous levels of mercury. This is true of some large species of fish that are higher up the food chain, because they accumulate mercury from their smaller prey and then we get a big dose when we eat them. Fish that have dangerous levels of mercury include king mackerel, marlin, orange roughy, shark, swordfish, tilefish, and bigeye tuna. Pregnant women and growing children in particular should take care to avoid these types of fish, because mercury can interfere with brain development. However, the same groups also stand to benefit from healthful omega-3 fatty acids, like DHA and EPA, which are helpful for brain development. Thus, it’s good for pregnant women and children to eat fish, so long as they avoid the ones with high levels of mercury. Most common types of fish have lower levels of mercury and can be eaten at least once per week, if not two or three times per week11. Learn more at this FDA page: Eating Fish: What Pregnant Women and Parents Should Know.

Self-Check

References:

- 1Eshel, G., Shepon, A., Makov, T., & Milo, R. (2014). Land, irrigation water, greenhouse gas, and reactive nitrogen burdens of meat, eggs, and dairy production in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(33), 11996–12001. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1402183111

- 2Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Sustainability. Retrieved from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/sustainability/#plate-and-planet

- 3Springmann, M., Godfray, H. C. J., Rayner, M., & Scarborough, P. (2016). Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(15), 4146–4151. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1523119113

- 4Aleksandrowicz, L., Green, R., Joy, E. J. M., Smith, P., & Haines, A. (2016). The Impacts of Dietary Change on Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Land Use, Water Use, and Health: A Systematic Review. PLOS ONE, 11(11), e0165797. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165797

- 5CDC. (2018, November 8). Drug Resistance & Food. Retrieved December 4, 2018, from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website: https://www.cdc.gov/features/antibiotic-resistance-food/index.html

- 6Dall, C. (2018, December 19). FDA reports major drop in antibiotics for food animals. Retrieved November 18, 2019, from Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy website: http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2018/12/fda-reports-major-drop-antibiotics-food-animals

- 7United States Department of Agriculture. (2103, July). Organic Livestock Requirements. Retrieved from https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/Organic%20Livestock%20Requirements.pdf

- 8Smith, T. C. (n.d.). What does ‘meat raised without antibiotics’ mean—And why is it important? Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2015/10/28/what-does-raised-without-antibiotics-mean-and-why-is-it-important/

- 10Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch Program. Ocean Issues. Retrieved November 18, 2019, from https://www.seafoodwatch.org/ocean-issues.

- 11U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2019, October 15). Advice about Eating Fish. Retrieved November 18, 2019, from http://www.fda.gov/food/consumers/advice-about-eating-fish

Image Credits:

- Fig 6.25. “Protein Scorecard” from the World Resources Institute is licensed under CC BY-4.0

- Fig 6.26. “Shifting High Consumers’ Diets Can Greatly Reduce Per Person Land Use and GHG Emissions” from the World Resources Institute is licensed under CC BY-4.0

- Fig 6.27. “Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Bacteria” by NIAID is licensed under CC BY 2.0

- Fig 6.28. “Antibiotic Resistance from Farm to Table infographic” from the CDC in in the Public Domain

- Fig 6.29. “Egg and sausage labels” by Alice Callahan is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Fig 6.30. “Screenshot from Seafood Watch app” by Alice Callahan licensed under CC BY 4.0