Food is a source of nutrients for our bodies, and as we’ve learned, the GI tract functions to extract those nutrients from food and absorb them into the body. But sometimes, specific foods can cause problems for the GI tract and the body, including food intolerances, food allergies, and celiac disease. These conditions are often confused for one another, but they have different causes, symptoms, and approaches to treatment.

Food Intolerances

A food intolerance occurs when a person has difficulty digesting a specific food or nutrient, causing unpleasant GI symptoms such as gas, bloating, flatulence, cramping, and diarrhea. Food intolerances are commonly caused by the body not producing enough of a particular digestive enzyme, so the symptoms generally involve the digestive system, and the severity of symptoms usually correlates with how much of the food was eaten. Unlike food allergies, the immune system does not play a role in food intolerance, and while the symptoms are unpleasant, they are generally not dangerous and will subside once the food passes out of the GI tract. People with food intolerances can also often consume small amounts of the offending food without symptoms.1

Lactose intolerance is a common food intolerance. People with lactose intolerance do not produce enough of the enzyme lactase, which is responsible for digesting the milk sugar lactose into single sugar molecules that can be absorbed in the small intestine. Undigested lactose can’t be absorbed, so it continues on to the large intestine. There, it draws more water into the large intestine, and bacteria metabolize the lactose, resulting in gas and acid production. These conditions cause the uncomfortable symptoms of gas, bloating, and diarrhea within about 30 minutes to two hours of consuming dairy foods.

As with most food intolerances, people with lactose intolerance can often consume some amount of lactose without discomfort, although this varies from person to person. Aged hard cheese, buttermilk, and yogurt (as long as it doesn’t include added milk solids) are often well-tolerated because they are low in lactose, which is consumed by bacteria during fermentation and aging. In addition, lactose-free milk and lactase enzyme supplements are available. Dairy products are some of the main dietary sources of calcium and vitamin D, so people who avoid dairy need to take special care to include other sources of these nutrients in their diets.2

Figure 3.17. Taking a lactase enzyme supplement allows many people with lactose intolerance to eat dairy products without suffering symptoms.

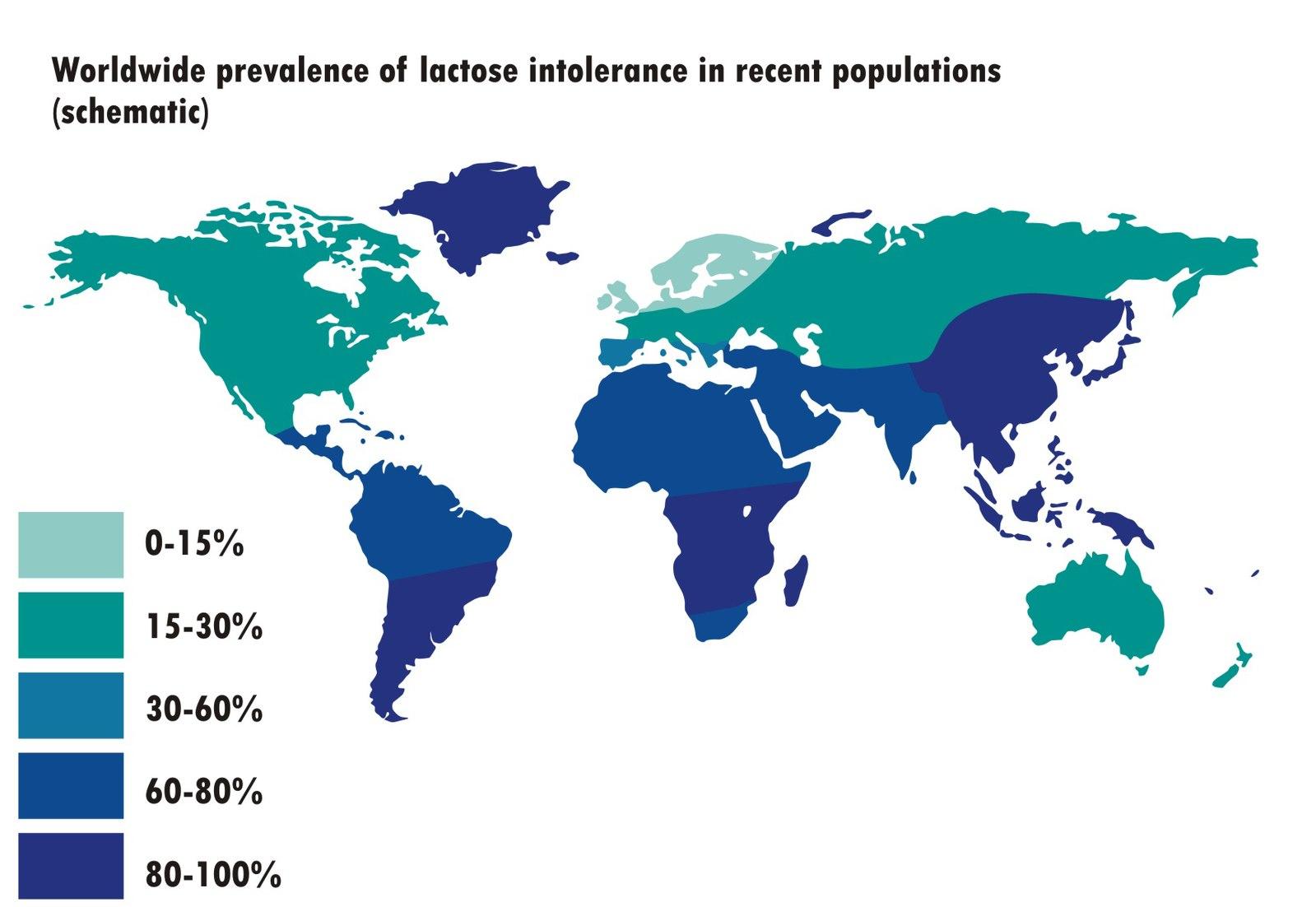

The vast majority of humans are born with the ability to digest lactose. All mammalian milk, including human milk, contains lactose, so historically, infants with lactose intolerance wouldn’t have survived. (Today, infants with lactose intolerance can consume soy-based infant formula.) Beyond infancy, lactose intolerance depends on your genes. In much of the world, it’s common for the activity of the lactase gene to decline with age, resulting in less lactase production and more lactose intolerance. Worldwide, 65% of the human population has some degree of lactose intolerance in adulthood. On the other hand, lactose tolerance is common in cultures where early domestication of dairy animals provided an important source of nutrition. In the U.S., adults of European descent can often tolerate lactose, whereas lactose intolerance is common among Asian Americans, African Americans, Mexican Americans, and Native Americans.3

Figure 3.18. The prevalence of lactose intolerance worldwide.

Food Allergies

In addition to its role in digestion, the GI tract serves an important immune function. Intestinal cells form the barrier between the interior of the body and the lumen, or tube, of the GI tract, which is technically outside of the body and teeming with potential pathogens. Immune tissue in the GI tract and other parts of the body produce immune cells that target foreign invaders, in part through the production of antibodies, protective proteins that bind to foreign substances. However, this function requires the immune system to accurately distinguish between normal food proteins and invading pathogens. A food allergy is what happens if the immune system mistakenly identifies a food protein as an invasive threat.

The most common type of food allergy involves immunoglobulin E (IgE), a type of antibody produced by the immune system in response to a specific substance, or allergen. Symptoms of an allergic reaction usually occur immediately after consuming the food (i.e., within seconds to minutes), although reactions can sometimes be delayed by two hours or more. Because an allergic reaction is caused by the immune system, it can lead to symptoms all over the body, including skin rashes; swollen lips, face, or throat; wheezing and difficulty breathing; nausea and vomiting; cramping; diarrhea; and rarely, a dangerous drop in blood pressure. A severe allergic reaction involving more than one organ system—a rash coupled with difficulty breathing, for example—is called anaphylaxis. Anaphylaxis can be life-threatening and should be treated immediately with epinephrine, commonly administered by injection with a device such as an EpiPen, and then person should seek immediate medical attention.1

Figure 3.19. Common food allergens: peanuts, dairy, wheat, eggs, and shrimp. At right, an EpiPen, containing injectable epinephrine, is pictured.

The most common food allergies in the U.S. are caused by proteins in peanuts, tree nuts, milk, shellfish, eggs, fish, wheat, soy and sesame.4,5 A 2019 study reported that 19% of adults in the U.S. believe they’re allergic to at least one food. After asking people about their symptoms, the researchers estimated that the true incidence of food allergies is closer to 11%, while the remaining 8% of people likely have a food intolerance.4

Food allergies are common in children, affecting about 8% of U.S. children, although allergies can also develop later in life.5 It’s common for young children to outgrow allergies to egg, dairy, wheat, or soy, but peanut, tree nut, and shellfish allergies are often lifelong. Recent research has found that letting babies eat common food allergens, particularly peanut products, can prevent the development of allergies, perhaps by allowing the immune system an early opportunity to learn to differentiate between food proteins and invading pathogens.6

If you think you may have a food allergy, it’s important to see an allergist to ensure you have an accurate diagnosis. Food allergies are diagnosed based on symptoms after consuming a food, specific IgE blood tests, and/or skin prick tests, where a tiny amount of food protein is scratched onto the skin to test for a reaction. Blood and skin tests determine whether a person is sensitized to an allergen, meaning that they’re producing IgE antibodies to the food. However, the presence of IgE antibodies doesn’t definitively mean a person has a food allergy; it’s common to have a positive IgE test but still be able to eat the food without symptoms. The gold standard test for diagnosing is an oral food challenge—consuming a small amount of the food and watching for signs of a reaction—although due to time, cost, and risk, these are not always conducted. If you are diagnosed with a food allergy, you will be counseled to strictly avoid the food and carry injectable epinephrine in case of accidental consumption. Unlike with food intolerances, consuming even a small amount of food can cause a serious reaction in those with food allergies.1

There are some promising new therapies for treating food allergies that involve exposing a person to small amounts of the allergen to try to teach the body to tolerate it. These don’t cure the allergy completely but may reduce the risk of a severe allergic reaction. The first of these therapies was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in January 2020.7

There are blood tests available that claim to screen for as many as 90 to 100 food allergies from one blood sample. These measure a different type of antibody called IgG, but the presence of IgG does not indicate a food allergy. Therefore, these tests are not recommended by allergy experts, because they may cause a person to unnecessarily fear and avoid a long list of foods to which they are not allergic.8

Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder affecting between 0.5 and 1.0% of people in the U.S., or one in every 100 to 200 people.9 In autoimmune diseases, the immune system produces antibodies that attack and damage the body’s own tissues. In the case of celiac disease, the body has an abnormal immune reaction to gluten (a group of proteins found in wheat, rye, and barley), causing antibodies to attack the cells lining the small intestine. This results in damage to the villi, decreasing the surface area for nutrient absorption. There is no cure for celiac disease, but it’s very effectively treated by eliminating gluten from the diet.10

Symptoms of celiac disease can range from mild to severe and can include pale, fatty, loose stools, gastrointestinal upset, constipation, abdominal pain, and skin conditions. Nutrient malabsorption can lead to weight loss and in children, a failure to grow and thrive. Symptoms can appear in infancy or much later in life, as late as age seventy. Celiac disease is not always diagnosed, because the symptoms may be mild. Even without symptoms, the disease can still damage the small intestine and impair nutrient absorption. Nutrient deficiencies can cause health problems over time, particularly in children and the elderly. For example, poor absorption of iron and folic acid can cause anemia, which impairs oxygen transport to cells in the body. Calcium and vitamin D deficiencies can lead to osteoporosis, a disease in which bones become brittle.

Diagnosis of celiac disease begins with a blood test for specific antibodies that are elevated in those with the disease. If the blood test is positive, the diagnosis is confirmed with a biopsy of the small intestine, a procedure in which a small amount of tissue is removed for examination. These tests may not accurately detect celiac disease in people already consuming a gluten-free diet, because without gluten, antibody levels may be low and damage to the small intestine may not be visible. This is why it’s best to be tested for celiac before eliminating gluten from the diet.

It isn’t clear what causes celiac disease; genetics play a role, but other factors also seem to influence its development. Celiac disease is most common in people of European descent and is rare in people of African American, Japanese, and Chinese descent. It is more prevalent in women and in people with type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, and Down and Turner syndromes.

Celiac disease is treated by completely avoiding gluten, as consuming even small amounts can cause intestinal damage. People with celiac can consume grains that don’t contain gluten, including rice, corn, millet, buckwheat, and quinoa. Oats can be consumed, although they are often contaminated with gluten from neighboring fields or shared processing equipment, so it’s best to buy oats labeled gluten-free. There are also an increasing number of gluten-free products available in stores. After eliminating gluten from the diet, the tissues of the small intestine usually heal within six months.

Figure 3.20. Celiac disease is caused by an autoimmune response to gluten, found in wheat, rye, and barley. At right is a section of the small intestine from a biopsy, visualized under a microscope, from a celiac patient. The villi, which would normally be finger-like projections, are blunted and flattened by damage caused by the disease.

Celiac disease is different from a wheat allergy in both cause and symptoms. Because celiac disease is an autoimmune condition, the cells of the small intestine come under attack, and damage causes chronic symptoms. A wheat allergy, on the other hand, is caused by antibodies attacking an allergen in the wheat itself, and the symptoms are usually immediate and acute.

Sometimes, people test negative for celiac disease but still believe that consuming gluten is causing symptoms, usually gastrointestinal in nature. They may eliminate gluten from their diet and find that they feel better. This is often called non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS). It’s not clear what causes NCGS or why a gluten-free diet is helpful. In some cases, it may be a placebo effect. In others, it seems that it’s not gluten causing the problem but other dietary components, such as FODMAPs, that happen to also be low in a gluten-free diet. And in some cases, gluten does seem to cause symptoms in people without celiac disease, although researchers don’t understand why.11,12

Except in the case of celiac disease, wheat allergy, or confirmed NCGS, gluten-free foods or a gluten-free diet are not inherently more healthful. In fact, packaged gluten-free foods are often more highly processed, with more added sugar, salt, and fat, compared to foods containing wheat. A gluten-free diet can also be lower in fiber, so those following the diet should be sure to include naturally gluten-free whole grains, legumes, nuts, fruits, and vegetables to provide adequate fiber.13

Self-Check:

Attributions:

- University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program, “Nutrition and Health,” CC BY-NC 4.0

References:

- 1Commins, S. P. (2020). Food intolerance and food allergy in adults: An overview. UpToDate. Retrieved February 28, 2020, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/food-intolerance-and-food-allergy-in-adults-an-overview?search=food%20intolerance&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- 2National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). (n.d.). Lactose Intolerance. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved February 28, 2020, from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/lactose-intolerance

- 3U.S. National Library of Medicine. Lactose intolerance. Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved February 28, 2020, from https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/lactose-intolerance#inheritance

- 4Gupta, R. S., Warren, C. M., Smith, B. M., Jiang, J., Blumenstock, J. A., Davis, M. M., Schleimer, R. P., & Nadeau, K. C. (2019). Prevalence and Severity of Food Allergies Among US Adults. JAMA Network Open, 2(1), e185630–e185630. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5630

- 5Gupta, R. S., Warren, C. M., Smith, B. M., Blumenstock, J. A., Jiang, J., Davis, M. M., & Nadeau, K. C. (2018). The Public Health Impact of Parent-Reported Childhood Food Allergies in the United States. Pediatrics, 142(6). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-1235

- 6Greer, F. R., Sicherer, S. H., Burks, A. W., Nutrition, C. O., & Immunology, S. on A. A. (2019). The Effects of Early Nutritional Interventions on the Development of Atopic Disease in Infants and Children: The Role of Maternal Dietary Restriction, Breastfeeding, Hydrolyzed Formulas, and Timing of Introduction of Allergenic Complementary Foods. Pediatrics, 143(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0281

- 7U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2020, February 20). FDA approves first drug for treatment of peanut allergy for children. FDA; FDA. http://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-drug-treatment-peanut-allergy-children

- 8American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology. (n.d.). The myth of IgG food panel testing. AAAAI. Retrieved March 2, 2020, from https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-and-treatments/library/allergy-library/IgG-food-test

- 9Choung, R. S., Unalp-Arida, A., Ruhl, C. E., Brantner, T. L., Everhart, J. E., & Murray, J. A. (2017). Less Hidden Celiac Disease But Increased Gluten Avoidance Without a Diagnosis in the United States: Findings From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys From 2009 to 2014. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 92(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.012

- 10Kelly, C. P., & Dennis, M. (2019, July 1). Patient education: Celiac disease in adults (Beyond the Basics). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/celiac-disease-in-adults-beyond-the-basics

- 11Hill, I. D. (2020, January 8). Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical manifestations of celiac disease in children. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-pathogenesis-and-clinical-manifestations-of-celiac-disease-in-children

- 12Francavilla, R., Cristofori, F., Verzillo, L., Gentile, A., Castellaneta, S., Polloni, C., Giorgio, V., Verduci, E., DʼAngelo, E., Dellatte, S., & Indrio, F. (2018). Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial for the Diagnosis of Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity in Children. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 113(3), 421–430. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2017.483

- 13Egan, S. (2018, January 12). Is There a Downside to Going Gluten-Free if You’re Healthy? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/12/well/eat/gluten-free-grain-free-diet.html

Images:

- Figure 3.17. “Home-breakfast (lactaid photo)” by Ernesto Andrade is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

- Figure 3.18. “Worldwide prevalence of lactose intolerance in recent populations” by NmiPortal is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

- Figure 3.19. “peanuts” by Tom Hermans; “cheese and bread on tray” by Alla Hetman; “fried eggs” by Gabriel Gurrola; “fried shrimp” by Jonathon Borba, all on Unsplash (license information); “Epi Pen” by Vu Nguyen is licensed under CC BY 2.0

- Figure 3.20. “bread” by Wesual Click on Unsplash (license information); “coeliac path” by Samir is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0