In early infancy, nutrition choices are relatively simple (though not necessarily easy!). When the baby is hungry, it’s time to breastfeed or prepare a bottle. But in later infancy and toddlerhood, a baby’s food horizons expand. This is an exciting period of learning about foods and how to eat with the rest of the family.

Introducing Solid Foods

The World Health Organization recommends that babies begin eating some solid foods at 6 months while continuing to breastfeed. Other health organizations offer more flexible advice, recommending that solid foods be introduced sometime between 4 and 6 months, depending on the baby’s development, interest in eating solids, and family preferences. Regardless, most babies aren’t ready to eat solid foods before 4 months, and starting too soon may increase the risk of obesity. Yet it’s also important not to start solids too late, as beyond 6 months, breast milk alone can’t support a baby’s nutrient requirements.1

However, as babies begin to eat solids, breast milk or formula continue to be the nutritional foundation of the diet. This period is also called complementary feeding, because solid foods are meant to complement the nutrients provided by breast milk or formula. Between 6 and 12 months, babies gradually eat more solid foods and less milk so that by 12 months, formula is no longer needed. Breastfeeding mothers may choose to wean at 12 months or continue breastfeeding as long as she and the baby like.

Babies should be developmentally ready to eat solids before trying their first foods. A baby ready for solids should be able to do the following:1

- Sit up without support (e.g., in a high chair or lap)

- Open mouth for a spoonful of food and swallow it without gagging or pushing it back out

- Reach for and grasp food or toys and bring them to his or her mouth

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends beginning with iron-rich foods such as pureed meat or iron-fortified cereal (e.g., rice cereal, oatmeal), as iron is usually the most limiting nutrient at this age, particularly for exclusively breastfed babies. Once these foods are introduced, others can gradually be added to the diet, introducing one at a time to keep an eye out for allergic reactions. Work up to a variety of foods from all of the food groups, as babies are willing to try just about anything at this stage, and this is an opportunity for them to learn about different flavors. You can also gradually increase texture, from pureed to mashed food, then lumpy foods to soft finger foods. By 12 months, most babies can eat most of the foods at the family table, with some modifications to avoid choking hazards.1,2

When choosing good complementary foods, there are three main goals: (1) to meet nutrient requirements; (2) to introduce potentially allergenic foods; and (3) to support your baby in learning to eat many different flavors and textures. Parents should be sure to include the following:1,2

- Good sources of iron and zinc, as both minerals can be limiting for breastfed infants. Good sources include meat, poultry, fish, and iron-fortified cereal. Beans, whole grains, and green vegetables add smaller amounts of iron.

- Adequate fat to support babies’ rapid growth and brain development. Good sources include whole fat yogurt, avocado, nut butters, and olive oil for cooking vegetables. Fish is also a great food for babies, because it provides both iron and fat, and it’s a good source of omega-3 fatty acids like DHA and EPA, which support brain development.

- A variety of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, so that your baby learns to like many different tastes and textures. It may take babies and toddlers 8 to 10 exposures of a new food before they learn to like it, so don’t be discouraged if your baby doesn’t like some foods right away.

There is no need to avoid giving your baby common food allergens, such as peanut, egg, dairy, fish, shellfish, wheat, soy, or tree nuts. In fact, studies indicate that introducing at least some of these foods during the first year can prevent food allergies from developing. The evidence is strongest for peanut allergy. A randomized controlled trial published in 2015, called the Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study, showed that in infants considered high-risk for food allergies, feeding peanut products beginning between 4 and 11 months reduced peanut allergy by 81 percent, compared with waiting to give peanuts until age 5.3 Similarly, early introduction of egg seems to protect children from developing an egg allergy.4,5 With any new food, keep an eye out for symptoms of an allergic reaction, such as hives, vomiting, wheezing, and difficulty breathing.6

Foods to Avoid in the First Year

There are only a few foods that should be avoided in the first year. These include the following:1

- Cow’s milk can’t match the nutrition provided by breast milk or formula and can cause intestinal bleeding in infants. However, dairy products such as yogurt and cheese are good choices for babies who have started solids. Babies can eat other dairy products, like yogurt and cheese, and cow’s milk can be added to the diet at 12 months.

- Plant-based beverages such as soy and rice milk aren’t formulated for infants, lack key nutrients, and often have added sugar.

- Juice and sugar-sweetened beverages have too much sugar. Whole fruit in a developmentally-appropriate form (pureed, mashed, chopped, etc.) is a better choice.

- Honey may contain botulism, which can make infants very ill.

- Unpasteurized dairy products or juices, and raw or undercooked meats or eggs, which can be contaminated with harmful foodborne pathogens.

- Added sugar and salt should be kept to a minimum so that your baby learns to like many different flavors and doesn’t develop preferences for very sweet or salty foods.

- Choking hazards such as whole nuts, grapes, popcorn, hot dogs, and hard candies should be avoided.

Responsive Feeding and Infant Growth

Regardless of whether infants are fed breast milk or formula, and continuing when they start solid foods, it’s important that caregivers use a responsive feeding approach. Responsive feeding is grounded in 3 steps:2

- The child signals hunger and satiety. This may occur through vocalizations (e.g., crying, talking), actions (e.g., pointing at food, or turning away when full), and facial expressions.

- The caregiver recognizes the cues and responds promptly and appropriately. For example, if the baby seems hungry, he or she is offered food promptly. If the baby turns his or her head or pushes away the breast, bottle, or an offered bite of food, the caregiver does not pressure the baby to eat more.

- The child experiences a predictable response to his or her signals.

With breastfeeding, responsive feeding simply means feeding the baby when he or she signals hunger, and the baby usually turns away, spits out the nipple, or falls asleep when full. With bottle-feeding, whether feeding breast milk or formula in a bottle, it’s a little trickier. It’s human nature to want the baby to finish the bottle that you’ve prepared, but a responsive feeding approach means that you let the baby decide when he or she has had enough. Pressure to eat more can cause the baby to grow too fast in infancy, which is correlated with becoming overweight or obese later in childhood. When feeding solid foods, the same responsive feeding principles apply, although solids should be offered at predictable meal- and snack-times to avoid constant grazing throughout the day. If babies are offered appropriate, nutrient-dense foods, and fed responsively, parents generally don’t need to worry about serving sizes or amounts eaten. They can trust that their babies will eat what they need.2

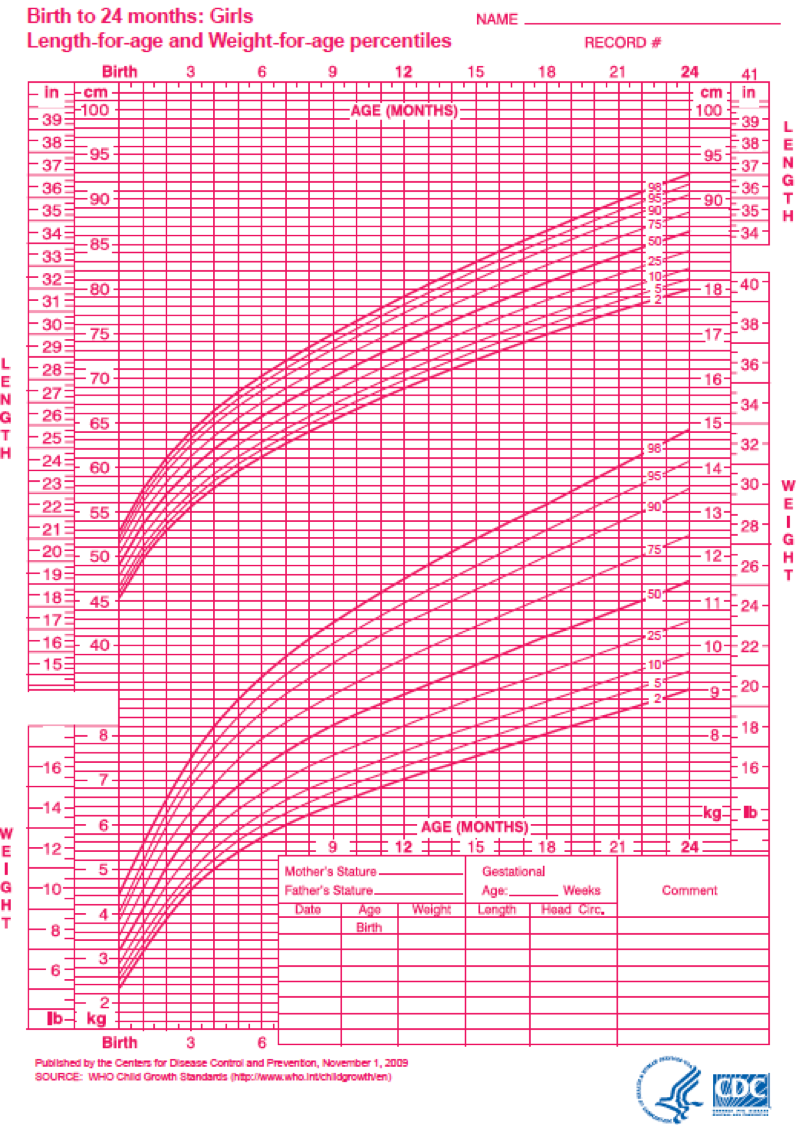

The best way to determine if children are getting enough food to eat is to track their growth. Pediatricians and other healthcare providers do this by measuring a child’s weight, length, and head circumference at each check-up and plotting their measurements periodically on growth charts from the World Health Organization. Growth charts allow you to compare your child’s growth to a population of other healthy children. Sometimes parents worry that if their child is in the 15th percentile for weight, that means she’s not growing well, but this isn’t the case. Children come in different shapes and sizes, and some grow faster than others. Thus, a child in the 15th percentile for weight may be a bit smaller than average, but when it comes to body size, the goal is not to be average or above average. The goal is to grow steadily and predictably in a way that is healthy for that individual child. If a child who was previously in the 15th percentile was suddenly measured at the 5th percentile or 50th percentile, that might indicate a health or nutrition problem that warrants further evaluation.7

Figure 11.6. WHO growth chart for girls from birth to 24 months.

Feeding Toddlers

Toddlerhood represents a stage of growing independence for children. They gain the physical abilities to feed themselves confidently, and their growing language skills mean they can verbalize food preferences more clearly. Gradually, through exposure and experience, they learn to eat foods more and more like the rest of their family.8

In the toddler years, it’s important to shift from a mindset of feeding “on demand,” which is appropriate for infants, to one of predictable structure, with sit-down meals and snacks (usually three meals and two to three snacks each day). This prevents constant grazing and means that children come to the table hungry, ready to enjoy a nourishing meal. As much as you can, sit down to meals together so that your toddler learns that part of the joy of eating is enjoying time with loved ones.2,8

The AMDRs for children ages 1 to 3 recommend that 45 to 65 percent of calories come from carbohydrate, 30 to 40 percent from fat, and 5 to 20 percent from protein. Compared with older children and adults, this balance of macronutrients includes a higher level of fat to support young children’s energy demands for growth and development. Therefore, fat or cholesterol generally should not be restricted in toddlers, although the focus should be on nutrient-dense sources of fat. Pediatricians usually recommend that toddlers ages 1 to 2 drink 2 to 3 cups of whole cow’s milk per day to provide fat, protein, and micronutrients, including calcium and vitamin D. At age 2, parents can switch to low-fat or nonfat milk to reduce fat intake. For toddlers with a family history or other risk factors for obesity, pediatricians may recommend switching to low-fat milk sooner. It is important for toddlers to not over-consume cow’s milk, as filling up on milk will reduce the consumption of other healthful foods. In particular, toddlers who drink too much cow’s milk have a greater risk of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia, which is a common nutrient for this age group and can cause deficits in brain development.8

Just as for adults, MyPlate can be helpful for planning balanced meals for children 2 and up, with appropriate serving sizes. A ballpark recommendation for serving sizes for children ages 2 to 6 is about 1 tablespoon per year of age for each food, with additional food provided based on appetite.8

Other recommendations for feeding toddlers include the following:2,8,9

- Continuing to offer a variety of foods from all of the food groups, including a mix of vegetables and fruits of different colors, tastes, and textures.

- Include whole grains and protein sources, such as poultry, fish, meats, tofu, or legumes in most meals and snacks.

- Limit salty foods and sugary snacks for health reasons, and so that your child doesn’t come to expect these tastes in foods.

- By 12 to 15 months, wean toddlers from a bottle, transitioning to giving milk at meals in a cup. Prolonged bottle use tends to promote overconsumption of milk and can cause dental caries, particularly when toddlers fall asleep with a bottle.

- Continue to take care with choking hazards, as many choking incidents happen in children younger than 4. Common choking hazards include hot dogs, hard candy, nuts, seeds, whole grapes, raw carrots, apples, popcorn, marshmallows, chewing gum, sausages, and globs of peanut butter. Ensuring that children are sitting down when eating can help to prevent choking accidents.

- Stick to cow’s milk and water as main beverage choices. Juice can be enjoyed occasionally in small servings (<0.5 cups/day) but is high in sugar, and whole fruit provides more nutrition. Plant-based beverages such as soy milk can be used in the case of a dairy allergy, lactose intolerance, or strong dietary preference, but be aware that these can be high in sugar and may not offer the same nutrients as cow’s milk, so check labels carefully. Flavored cow’s milk, soda, sports drinks, energy drinks, and caffeinated beverages should be avoided.

- Most children can get all of the nutrients they need from their diet, even if it seems that their intake is variable and they are somewhat picky about their choices. Pediatricians may prescribe a fluoride supplement for children living in areas with low fluoride levels in drinking water. They may also recommend a vitamin D supplement for children who do not consume adequate levels in their diet.

Self-Check:

Attributions:

- University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program. (2018). Lifespan Nutrition From Pregnancy to the Toddler Years. In Human Nutrition. http://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition/

References:

- 1American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. (2014). Complementary Feeding. In Pediatric Nutrition (7th ed., pp. 123–139). American Academy of Pediatrics.

- 2Perez-Escamilla, R., Segura-Perez, S., & Lott, M. (2017). Feeding Guidelines for Infants and Young Toddlers: A Responsive Parenting Approach. Healthy Eating Research. http://healthyeatingresearch.org

- 3Du Toit, G., Roberts, G., Sayre, P. H., Bahnson, H. T., Radulovic, S., Santos, A. F., Brough, H. A., Phippard, D., Basting, M., Feeney, M., Turcanu, V., Sever, M. L., Gomez Lorenzo, M., Plaut, M., & Lack, G. (2015). Randomized Trial of Peanut Consumption in Infants at Risk for Peanut Allergy. New England Journal of Medicine, 0(0), null. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1414850

- 4Burgess, J. A., Dharmage, S. C., Allen, K., Koplin, J., Garcia-Larsen, V., Boyle, R., Waidyatillake, N., & Lodge, C. J. (2019). Age at introduction to complementary solid food and food allergy and sensitization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical and Experimental Allergy: Journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 49(6), 754–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.13383

- 5Greer, F. R., Sicherer, S. H., Burks, A. W., Nutrition, C. O., & Immunology, S. on A. A. (2019). The Effects of Early Nutritional Interventions on the Development of Atopic Disease in Infants and Children: The Role of Maternal Dietary Restriction, Breastfeeding, Hydrolyzed Formulas, and Timing of Introduction of Allergenic Complementary Foods. Pediatrics, 143(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0281

- 6American Academy of Pediatrics. (2018). Food Allergies in Children. HealthyChildren.Org. Retrieved September 9, 2020, from https://www.healthychildren.org/English/healthy-living/nutrition/Pages/Food-Allergies-in-Children.aspx

- 7American Academy of Pediatrics. (2015). How to Read a Growth Chart: Percentiles Explained. HealthyChildren.Org. Retrieved September 3, 2020, from https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/Glands-Growth-Disorders/Pages/Growth-Charts-By-the-Numbers.aspx

- 8American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. (2014). Feeding the Child. In Pediatric Nutrition (7th ed., pp. 143–173). American Academy of Pediatrics.

- 9Lott, M., Callahan, E., Welker Duffy, E., Story, M., & Daniels, S. (2019). Consensus Statement. Healthy Beverage Consumption in Early Childhood: Recommendations from Key National Health and Nutrition Organizations (No. 1111). Healthy Eating Research.

Image Credits:

- Baby eating egg photo by life is fantastic on Unsplash (license information)

- “Mimi feeding 2” by Pomainhilippe Put is licensed under CC BY 2.0

- Figure 11.6. “Girls length-for-age and weight-for-age percentiles” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain