9 Leading in Groups

Learning Objectives

- Identify situations where you may need to enact different leadership styles or strategies based on the context and needs of your group

- Distinguish between transactional and transformative leaders

- Identify the four characteristics of transformative leaders

In the previous chapter, you were introduced to definitions of leaders and leadership and to the various ways leaders are identified and emerge in groups. In this chapter, we will dive deeper into two specific theories and approaches to leadership relevant to groups and teams, specifically situational leadership and transformational leadership.

Situational Leadership

Situational leadership, or leadership in context, means that leadership itself depends on the situation at hand. In sharp contrast to the idea of a “natural born leader” found in traits approaches to leadership, this viewpoint is relativist. Leadership is relative or varies, based on the context. There is no one “universal trait” to which we can point or principle to which we can observe in action. No style of leadership is more or less effective than another unless we consider the context. Then our challenge presents itself: how to match the most effective leadership strategy with the current context?

To match leadership strategies and context we first need to discuss the range of strategies as well as the range of contexts. While the strategies list may not be as long as we might imagine, the context list could go on forever. If we were able to accurately describe each context, and discuss each factor, we would quickly find the task led to more questions, more information, and the complexity would increase, making an accurate description or discussion impossible. Instead, we can focus our efforts on factors that each context contains and look for patterns, or common trends, that help us make generalizations about our observations.

For example, an emergency may require a leader to be direct, giving specific orders to each person. Since each second counts, the quick thinking and actions at the direction of a leader may be the most effective strategy. To stop and discuss, vote, or check everyone’s feelings on the current emergency situation may waste valuable time. That same approach applied to common governance or law-making may indicate a dictator is in charge, and that individuals and their vote are of no consequence. Instead, an effective leader in a democratic process may ask questions, gather viewpoints, and seek common ground as lawmakers craft a law that applies to everyone equally.

Hersey and Blanchard Model of Situational Leadership

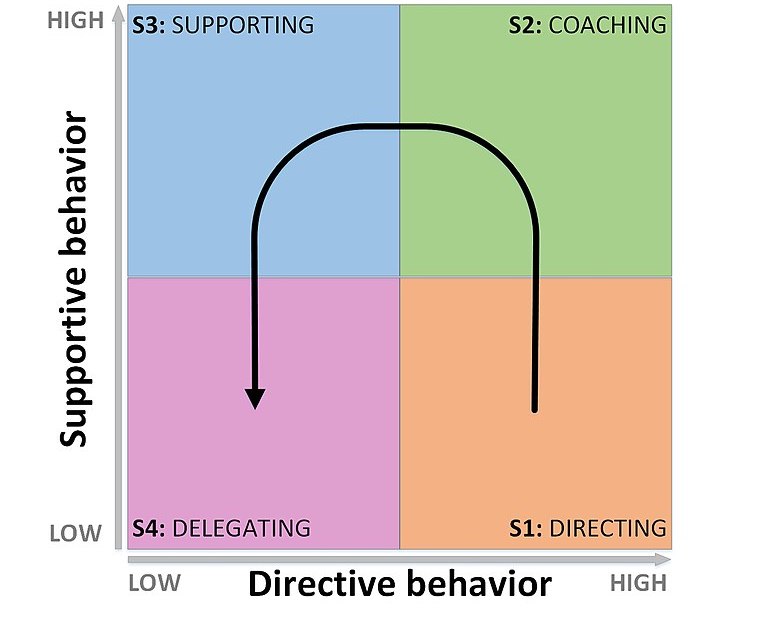

Hersey and Blanchard (1977) take the situational framework and apply it to an organizational perspective that reflects our emphasis on group communication. They assert that to be an effective manager, one needs to change their leadership style based on the context, including the skills, knowledge, and motivation of the people they are leading and the task details. Hersey and Blanchard focus on two key issues: tasks and relationships, and present the idea that we can to a greater or lesser degree focus on one or the other to achieve effective leadership in a given context. They offer four distinct leadership styles or strategies (abbreviated with an “S”):

- Directing (S1). Leaders tell people what to do and how to do it.

- Coaching (S2). Leaders provide direction, information, and guidance, but sell their message to gain compliance among group members.

- Supporting (S3). Leaders focus on the relationships with group members and shares decision-making responsibilities with them.

- Delegating (S4). Leaders focus on relationships, rely on professional expertise or group member skills, and monitor progress. They allow group members to be more directly responsible for individual decisions but may still participate in the process.

Directing and coaching strategies are all about getting the task done. Supporting and delegating styles are about developing relationships and empowering group members to get the job done. Each style or approach is best suited, according to Hersey and Blanchard, to a specific context. Again, assessing a context can be a challenging task but they indicate the focus should be on the development level of the group members. It is a responsibility of the leader to assess the group members and the degree to which they possess the ability to work independently or together effectively, including whether they have the competence, or the right combination of skills and abilities that the task requires, as well as the commitment or motivation to complete the task. Once again, they offer us four distinct levels (abbreviated with “D” for development):

- D1, or level one (low competence and high commitment). This is the most basic level where group members lack the skills, prior knowledge, skills, or self-confidence to accomplish the task effectively. They need specific directions, and systems of rewards and punishment (for failure) may be featured. They will need external motivation from the leader to accomplish the task.

- D2, or level two (some competence and low commitment) At this level the group members may possess the motivation, or the skills and abilities, but not both. They may need specific, additional instructions or may require external motivation to accomplish the task.

- D3, or level three (high competence and some commitment). At this level we can observe group members who are ready to accomplish the task, are willing to participate, but may lack confidence or direct experience, requiring external reinforcement and some supervision.

- D4, or level four (high competence and high commitment). Finally, we can observe group members that are ready, prepared, willing, and confident in their ability to solve the challenge or complete the task. They require little supervision.

Now it is our task to match the style or leadership strategy to the development level of the group members as shown in the table below.

| Leadership Style (S) | Development Level (D) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | S1 | D1 |

| 2 | S2 | D2 |

| 3 | S3 | D3 |

| 4 | S4 | D4 |

This is one approach to situational leadership that applies to our exploration of group communication, but it does not represent all approaches. What other factors might you consider? How might we assess diversity, for example, in this approach? We might have a skilled professional who speaks English as their second language, and who comes from a culture where constant supervision is viewed as controlling or domineering, and if a leader takes an S1 approach to provide leadership, we can anticipate miscommunication and even frustration. The effective group communicator recognizes the Hersey-Blanchard approach provides insight and possible solutions to consider but also keeps the complexity of the context in mind when considering a course of action.

Path-Goal Theory

A second situational leadership theory comes from Robert J. House and Martin Evans. Like Hersey and Blanchard, they assert that the type of leadership needed to enhance organizational effectiveness depends on the situation in which the leader is placed.

The model of leadership advanced by House and Evans is called the path-goal theory of leadership because it suggests that an effective leader provides organizational members with a path to a valued goal. According to House (1971), the motivational function of the leader consists of increasing personal payoffs to organizational members for work-goal attainment, and making the path to these payoffs easier to travel by clarifying it, reducing roadblocks and pitfalls, and increasing the opportunities for personal satisfaction en route.

Effective leaders, therefore, provide rewards that are valued by group members. In an organization, these rewards may be pay, recognition, promotions, or any other item that gives members an incentive to work hard to achieve goals. Effective leaders also give clear instructions so that ambiguities about work are reduced and followers understand how to do their jobs effectively. They provide coaching, guidance, and training so that followers can perform the task expected of them. They also remove barriers to task accomplishment, correcting shortages of materials, inoperative machinery, or interfering policies.

According to the path-goal theory, the challenge facing leaders is basically twofold. First, they must analyze situations and identify the most appropriate leadership style. For example, experienced employees who work on a highly structured assembly line don’t need a leader to spend much time telling them how to do their jobs—they already know this. The leader of an archeological expedition, though, may need to spend a great deal of time telling inexperienced laborers how to excavate and care for the relics they uncover.

Second, leaders must be flexible enough to use different leadership styles as appropriate. To be effective, leaders must engage in a wide variety of behaviors. Without an extensive repertoire of behaviors at their disposal, a leader’s effectiveness is limited (Hoojiberg, 1996). All team members will not, for example, have the same need for autonomy. The leadership style that motivates organizational members with strong needs for autonomy (participative leadership) is different from that which motivates and satisfies members with weaker autonomy needs (directive/instrumental leadership). The degree to which leadership behavior matches situational factors will determine members’ motivation, satisfaction, and performance (see Figure 1; House & Dessler, 1974; House & Mitchell, 1974).

According to path-goal theory, there are four important dimensions of leader behavior, each of which is suited to a particular set of situational demands (House & Dessler, 1974; House & Mitchell, 1974; Keller, 1989).

- Supportive leadership—At times, effective leaders demonstrate concern for the well-being and personal needs of organizational members. Supportive leaders are friendly, approachable, and considerate to individuals in the workplace. Supportive leadership is especially effective when an organizational member is performing a boring, stressful, frustrating, tedious, or unpleasant task. If a task is difficult and a group member has low self-esteem, supportive leadership can reduce some of the person’s anxiety, increase his confidence, and increase satisfaction and determination as well.

- Directive/instrumental leadership—At times, effective leaders set goals and performance expectations, let organizational members know what is expected, provide guidance, establish rules and procedures to guide work, and schedule and coordinate the activities of members. Directive leadership is called for when role ambiguity is high. Removing uncertainty and providing needed guidance can increase members’ effort, job satisfaction, and job performance.

- Participative leadership—At times, effective leaders consult with group members about job-related activities and consider their opinions and suggestions when making decisions. Participative leadership is effective when tasks are unstructured. Participative leadership is used to great effect when leaders need help in identifying work procedures and where followers have the expertise to provide this help.

- Achievement-oriented leadership—At times, effective leaders set challenging goals, seek improvement in performance, emphasize excellence, and demonstrate confidence in organizational members’ ability to attain high standards. Achievement-oriented leaders thus capitalize on members’ needs for achievement and use goal-setting theory to great advantage.

Overall, there is no “One Size Fits All” leadership approach that works for every context, but the situational leadership viewpoint reminds us of the importance of being in the moment and assessing our surroundings, including our group members and their relative strengths and areas of emerging skill.

Transformational Leadership

Our second approach, transformational leadership, emphasizes the vision, mission, motivations, and goals of a group or team and motivates them to accomplish the task or achieve the result. This model of leadership asserts that people will follow a person who inspires them, who clearly communicates their vision with passion, and helps get things done with energy and enthusiasm.

James MacGregor Burns (1978), a presidential biographer, first introduced the concept, discussing the dynamic relationship between the leader and the followers, as they together motivate and advance towards the goal or objective. Bass (1985) contributed to his theory, suggesting there are four key components of transformation leadership:

- Idealized Influence: Transformational leaders serve as role models, demonstrating expertise, skills, and talent that others seek to emulate, inspiring positive actions while reinforcing trust and respect.

- Inspirational Motivation: Transformational leaders communicate a clear vision, helping followers understand the individual steps necessary to accomplish the task or objective while sharing in the anticipation of completion.

- Individualized Consideration: Transformational leaders recognize and celebrate each follower’s unique contributions to the group.

- Intellectual stimulation: Transformational leaders encourage creativity and ingenuity, challenging the status quo, and encouraging followers to explore new approaches and opportunities.

The leader conveys the group’s goals and aspirations, displays a passion for the challenge that lies ahead, and demonstrates a contagious enthusiasm that motivates group members to succeed. This approach focuses on the positive changes that need to occur for the group to be successful and requires the leader to be energetic and involved with the process, even helping individual members complete their respective roles or tasks.

Transformational leadership is considered to be distinct from transactional models of leadership. Bryman (1992) wrote that transactional leaders exchange rewards for performance. Transformational leaders, by contrast, provide group members with a vision to which they can all aspire. They also work to develop a team spirit so that it becomes possible to achieve that vision.

Den Hartog, Van Muijen, and Kopman (1997) distinguished clearly between these two kinds of leaders. They held that transactional leaders motivate group members to perform as expected, whereas transformational leaders inspire followers to achieve more than what is expected. Nanus (1992) wrote that transformational leaders accomplish these tasks by instilling pride and generating respect and trust; by communicating high expectations and expressing important goals in straightforward language; by promoting rational, careful problem-solving; and by devoting personal attention to group members.

Review & Reflection Questions

- Should our approach to leadership depend on the context? Why or why not?

- Using the two different theories of situational leadership, what leadership styles or strategies might be appropriate to use in your group? Why?

- What is the difference between a transactional and a transformational leader? What examples of transformational leadership have you observed?

References

- Bass, B. (1985). Leadership and performance. Free Press.

- Bryman, A. (1992). Charisma and leadership in organizations. Sage.

- Burns, J. (1978). Leadership. Harper and Row.

- Den Hartog, D.N., Van Muijen, J.J., & Kopman, P.L. (1997). Transactional versus transformational leadership: An analysis of the MLQ (Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire). Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70, 19–35.

- Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1977). Management of organizational behavior (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Hoojiberg, R. (1996). A multidimensional approach toward leadership: An extension of the concept of behavioral complexity. Human Relations, 49(7), 917–946.

- House, R. J. (1971). A path-goal theory of leader effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 16, 321–333.

- House, R. J., & Dessler, G. (1974). The path-goal theory of leadership: Some post hoc and a priori tests. In J. Hunt & L. Larson (eds.). Contingency approaches to leadership. Southern Illinois University Press.

- House, R. J., & Mitchell, T. R. (1974). Path-goal theory of leadership, Journal of Contemporary Business, 5, 81-94.

- Keller, R. T. (1989). A test of the path-goal theory of leadership with need for clarity as a moderator in research and development organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 208–212.

- Nanus, D. (1992). Visionary leadership: Creating a compelling sense of direction for your organization. Jossey-Bass.

Authors & Attribution

The majority of the content in this chapter is adapted and remixed from “Group Leadership” from An Introduction To Group Communication. This content is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

The section on “Path-Goal Theory” in this chapter was adapted from Bright, D.S., & Cortes, A. H. (2019). Principles of management. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/principles-management. Access the full chapter for free here. The content is available under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license.

a theory and approach to leadership in which the leadership style or strategy varies based on the context as well as the motivation and competencies of group members

a leadership theory and approach that suggests that an effective leader provides organizational members with a path to a valued goal

a leadership style in which the leader demonstrates concern for the well-being and personal needs of organizational members

a leadership style in which the leader sets goals and performance expectations, lets organizational members know what is expected, provides guidance, establishes rules and procedures to guide work, and schedules and coordinates the activities of members

a leadership style in which the leader consults with group members about job-related activities and considers their opinions and suggestions when making decisions

a leaderships style in which leaders set challenging goals, seek improvement in performance, emphasize excellence, and demonstrate confidence in organizational members’ ability to attain high standards

an approach to leadership that emphasizes the relationship between the leader and follower, with a focus on inspiring change in both the leader and the followers

an approach to leadership that focuses on the leader and follower relationship in which the leader exchanges rewards and punishment for the follower's performance