What Impression Did Residential Staff Try to Create with Photos?

When residential school staff took photos of children playing sports like hockey or participating in school activities, they were often trying to create a false impression that these schools were positive, supportive places for Indigenous children. These images were used as propaganda, meant to convince the public that the schools were helping Indigenous children “improve” by teaching them discipline, teamwork, and Canadian values through sports.

In reality, these images hid the truth. As Survivors like Eugene Arcand have said, the photos were used to “show off” students while ignoring the emotional, physical, and cultural abuse happening behind the scenes. These carefully staged moments made it seem like students were happy and thriving, while in truth, sports were often used as a way to control, assimilate, and even punish students. The images served the colonial goal of justifying the residential school system, rather than telling the real stories of the children’s experiences.

So while the kids in the photos may have been smiling or playing hockey, the photos didn’t show the harsh discipline, the loneliness, the fear of losing, or the forced separation from their families and cultures.

Healing Through the Game: How Sport Acts as Medicine in Indigenous Lives

Sport is more than just competition or exercise it can be a powerful form of medicine. For many Indigenous people, sport has provided healing from trauma, a way to express cultural identity, and a path toward emotional and spiritual well-being. In the video “Sport as Medicine”, Aiden Baker and other Indigenous voices explain how sports, especially lacrosse, have helped them cope with personal challenges while also connecting them to community, tradition, and resilience.

Aiden Baker, a member of the Calano reservation, shares that lacrosse has been his personal medicine. He has played the sport for over 23 years, starting from a young age and eventually pursuing his dream of playing college lacrosse at Ottawa University. His accomplishments, including becoming a two-time All-American and Offensive Player of the Year, speak to his dedication. But for Aiden, lacrosse is about more than winning it’s about survival. Raised in a family that valued lacrosse, Aiden was mentored by his grandfather, a residential school Survivor and Hall of Fame athlete. This connection gave him strength, and showed him how sport could be a way to reclaim pride and purpose, even in the face of generational trauma.

Aiden also highlights how sport helped him reconnect with his cultural heritage and language. His great-grandfather, Ray Baker, used their ancestral language while playing lacrosse a strategic advantage that also reflected cultural pride. In contrast to the residential school system, which tried to erase Indigenous languages and traditions, sport became a space to hold on to and honour those identities. Even though many Indigenous students in residential schools faced physical and emotional abuse, moments on the playing field could offer a rare sense of freedom, dignity, and self-expression.

Beyond the personal and cultural, sport is described as a form of therapy. Aiden talks about how playing different sports, such as basketball, soccer, and track, helped him navigate life’s difficulties. Sports became an emotional outlet helping him deal with anger, stress, and sadness in a healthy way. They also opened doors to opportunities, like scholarships, that supported his education and future. This reflects how sports can serve as tools of empowerment, especially for Indigenous youth facing systemic barriers.

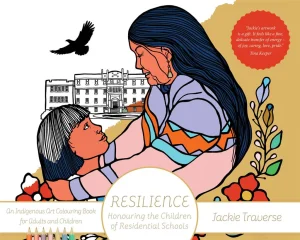

Lacrosse, in particular, holds a special place in many Indigenous cultures as the “medicine game.” It is considered a gift from the Creator, played not just for fun or competition, but for healing. Lacrosse can help players and communities address hardship, strengthen relationships, and reconnect with traditional values. Aiden emphasizes that lacrosse brings people together and helps create unity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. It becomes a space for reconciliation, where mutual respect and shared understanding can grow.

Finally, Aiden offers a call to action. He encourages all people, especially settlers to be open-minded, respectful, and willing to walk alongside Indigenous communities in their journey toward healing. He reminds us that the legacy of colonialism still affects Indigenous people today, but through sport and cultural revival, there is hope for a stronger, more connected future. As Aiden says, Indigenous communities are not only surviving they are thriving. Sport, as medicine, continues to be a powerful part of that story.

Still Playing by Colonial Rules: Waneek Horn-Miller’s Critique of Indigenous Sport Development

When Waneek Horn-Miller says that the government is “trying but still approaching Indigenous sport development in a very colonial way,” she is highlighting how many current efforts to support Indigenous athletes still follow settler-led systems that control how sports are offered, organized, and valued. Even though funding and programs have increased since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, Horn-Miller points out that the government’s approach continues to reflect a paternalistic mindset—treating Indigenous athletes as if they need saving or guidance, rather than recognizing their ability to lead and shape sport based on their own cultural knowledge and priorities.

Residential Schools and the Hockey Myth

Historically, sports like hockey were introduced into residential schools as a way to “civilize” Indigenous children. In Forsyth and McKee’s case study, they explain how hockey became a symbol of unity and Canadian identity—but only on colonial terms. Residential school staff used sports photos to promote the idea that Indigenous children were thriving in the schools. But as Survivor Eugene Arcand revealed, these images were staged and misleading. For example, he described a hockey team photo that showed students wearing brand-new equipment that they never actually used. He explained that some boys in the photo had hidden their swollen hands behind their backs after being severely punished the day before. These photos were propaganda tools, designed to show that the schools were helping Indigenous children, while covering up the abuse and trauma that students were really experiencing.

This legacy still impacts how Indigenous athletes are treated today. Many government sport programs continue to be designed and run by non-Indigenous people, often without real input from the communities they’re meant to serve. This continues the idea that Indigenous peoples are “fortunate beneficiaries” of Canada’s generosity, instead of recognizing them as powerful leaders of their own sport systems.

Rilee ManyBears and Systemic Barriers

Rilee ManyBears is a long-distance runner from the Siksika First Nation and a third-generation residential school survivor. He found healing and purpose in running, inspired by stories of how Indigenous messengers once ran between communities to carry news. Sports helped him escape the impacts of poverty, addiction, and violence in his community. He became a gold medalist at the World Indigenous Games and aimed to qualify for the Olympics.

But Rilee’s story also shows the unequal playing field Indigenous athletes face. He had to overcome barriers like lack of training facilities, funding, and visibility. Even though Canada spent $53 million on Indigenous sports development by 2022, the Canadian Olympic Committee still doesn’t track how many Indigenous athletes represent the country, showing a serious lack of attention and accountability. For Tokyo 2020, only one Indigenous athlete, Jillian Weir, was confirmed. These are clear examples of how systemic inequality continues, even when money is being invested.

The Problem with “Sport for Development” Programs

Waneek Horn-Miller’s critique also ties into a larger issue: the way sport is often used by governments and organizations to “fix” Indigenous communities, rather than support their self-determined goals. This is known as the “sport for development” model. While these programs are often well-intentioned, they are based on Euro-Canadian values of success, such as winning, individual achievement, and national pride, instead of Indigenous understandings of sport as a communal, spiritual, or cultural activity.

For example, lacrosse a traditional Indigenous game often referred to as the “medicine game” was banned in some contexts and replaced by hockey in residential schools. Now, when the government funds hockey programs for Indigenous youth without recognizing or supporting traditional games or teachings, it continues to promote colonial values of what sport should look like.