In teacher-led research, educators play dual roles as both researchers and decision-makers in their classrooms. Mitchell (2004) highlights that teaching inherently involves efforts to enhance student learning by adjusting instructional methods.

This process is akin to conducting a study in the classroom to observe what is or isn’t working. As part of their everyday routine, teachers intervene, gather data, and implement necessary modifications. Mitchell notes that most research projects conducted by teachers pose minimal to no risk to students (p. 1438-1439).

Ethical Teachers, Ethical Researchers

Researchers need to be able to demonstrate that they are aware of these obligations, of the sorts of unpredictable outcomes that they may face, the possible ethical implications of these and how they deal with them.”

(Mitchell; pp. 1438-1439)

When instructors research their own professional practices to fulfill academic requirements that include the participation of others with whom they already have a relationship, such as their students, they assume the dual-role of practitioner and researcher.

Research conducted in this context typically raises two main issues that require particular attention:

Dual Relationships

Dual relationships exist between the researcher and participants when people in positions of status (“power-over”) or undue influence undertake research in addition to their already established roles and responsibilities, and the research will potentially involve individuals of lesser power or status such as students.

Participant Privacy

Information and results obtained from studying one’s own practice are made public through research reports, presentations (e.g. showing data/results), etc. The release of results could compromise the privacy or status of participants. The potential harm to the participants cannot outweigh the potential benefits to them.

Power-Over

Even when a practitioner-researcher perceives that his/her workplace, school or classroom has a “warm and friendly” atmosphere of trust and openness between teachers-students, the quality of these relationships does not address the underlying differences in status and influence that structure the nature of the relationships. Therefore, the researcher needs to recognize the structure of the relationships to assess the role of power-over in the research context.

The researcher needs to be especially attentive to the role of power-over. Students at a school, can be “captive audiences” for research particularly when a study is conducted by their own teacher, or even another teacher or member at their school rather than a person who they do not know.

Examples of power-over relationships

- A student may not know that s/he can refuse a teacher’s request to use a sample of their classroom work for research since it was a required assignment;

- A student may perceive that not participating in an instructor’s study will disadvantage their grade.

Scenario

Classroom Assignment as Research Material

Play through the following scenarios to view examples of power-over interactions and how they can be handled when obtaining student permission for your research study. You can view the scenario in full screen mode by clicking on the expand arrow icon.

Teachers who conduct research in their classes should think through the power differentials in the relationships they have with students.

Reflect

Power-over Relationship

Think about your own instructor/researcher-student relationship and how this relationship can be a power-over relationship.

The ethical issues associated with dual-role research must be considered when designing your research plan. You should provide adequate procedures for mitigating or minimizing the power-over differences that are part of the dual-role relationship. It is the job of the researcher to think through, explain, and justify the ethical approach and procedures in the research plan.

General Ways to Mitigate the Power-over Relationship

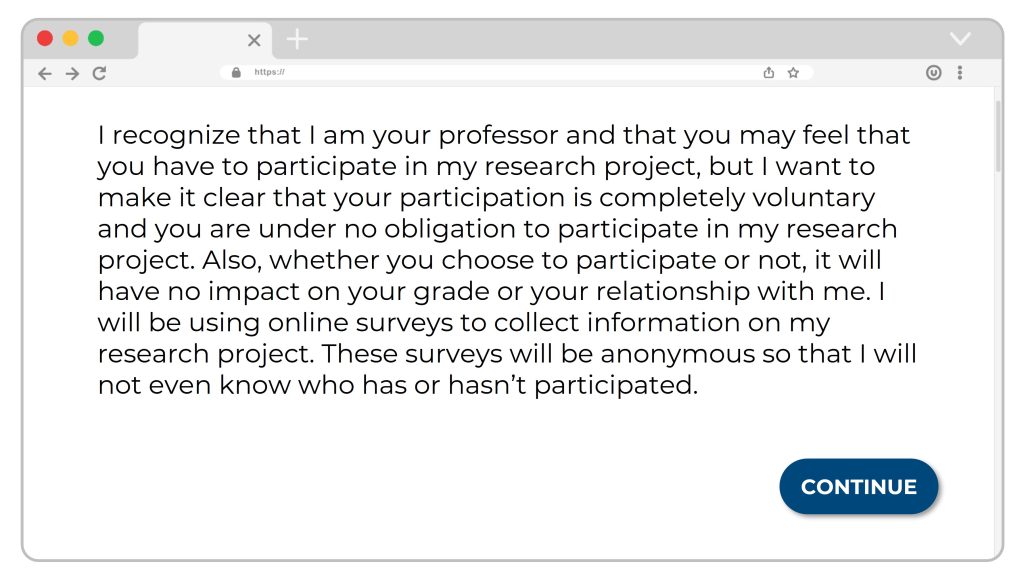

When explaining your research project to students as part of the consent process, be sure to declare the power-over situation and the safeguards you will use to prevent undue influence such as inducement, pressure, obligation, and coercion during participation. The following is an example:

Sample Disclaimer Text (from the image above)

“I recognize that I am your professor and that you may feel that you have to participate in my research project, but I want to make it clear that your participation is completely voluntary and you are under no obligation to participate in my research project. Also, whether you choose to participate or not, it will have no impact on your grade or your relationship with me. I will be using online surveys to collect information on my research project. These surveys will be anonymous so that I will not even know who has or hasn’t participated.”

Administering paper-based surveys for anonymity

- Assign a student or another colleague to administer the survey.

- Ensure there is no power-over relationship with the survey administrator.

Maintain a neutral tone when explaining your research project

- Avoid emotional appeals.

- Do not emphasize the project’s importance to you.

- Refrain from statements like “I am counting on your participation.”

- Avoid overstating potential benefits or promoting participation based on research importance or outcomes.