Chapter 7: Writing Great Paragraphs

Introductory and Concluding Paragraphs

Picture your introduction as a storefront window: you have a certain amount of space to attract your customers (readers) to your goods (subject) and bring them inside your store (discussion). Once you have enticed them with something intriguing, you then point them in a specific direction and try to make the sale (convince them to accept your thesis).

Your introduction is an invitation to your readers to consider what you have to say and then to follow your train of thought as you expand upon your thesis statement.

An introduction serves the following purposes:

- Establishes your voice and tone, or your attitude, toward the subject

- Introduces the general topic of the essay

- States the thesis that will be supported in the body paragraphs

- Provides signposts of what you will discuss in your essay

First impressions are crucial and can leave lasting effects in your reader’s mind, which is why the introduction is so important to your essay. If your introductory paragraph is dull or disjointed, your reader probably will not have much interest in continuing with the essay.

Attracting Interest in Your Introductory Paragraph

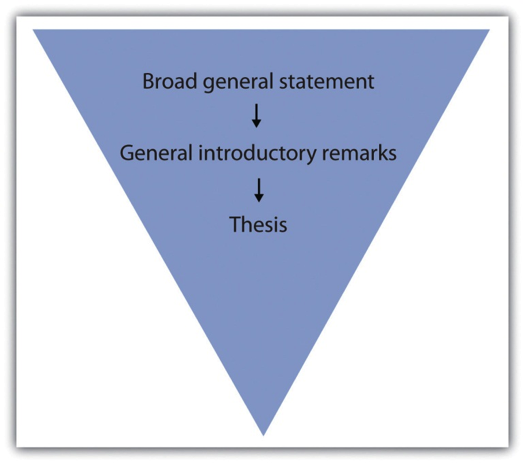

Your introduction should begin with an engaging statement devised to provoke your readers’ interest. In the next few sentences, introduce them to your topic by stating general facts or ideas about the subject. As you move deeper into your introduction, you gradually narrow the focus, moving closer to your thesis. Moving smoothly and logically from your introductory remarks to your thesis statement can be achieved using a funnel technique, as illustrated in Figure 7.1: Funnel Technique.

Self-Practice Exercise 7.6

H5P: Capturing Attention

Imagine you are writing an essay arguing for domesticated cats to be kept indoors. What follows are a list of potentially attention-grabbing first sentences for the introductory paragraph. Match the kind of appeal to the best example of it in the list.

Examples:

- A little girl weeps at the untimely death of her beloved cat; an elderly neighbour misses the company of the neighbourhood songbirds.

- Most people love neighbourhood wildlife and most pet owners love their pets; a mutually beneficial strategy for keeping both safe is to keep cats indoors.

- Cats are cute, but they are also murderous killing machines bent on destroying your neighbourhood.

- Every year, cats kill between 100 million and 350 million birds in Canada alone; 38% of those birds are killed by domesticated cats.

- If you knew there was one single behavioural change that would improve your neighbourhood for generations, would you do it?

- The purpose of this essay is to protect neighbourhood wildlife from cats, and to protect cats from the hazards of this neighbourhood.

- “Curiosity killed the cat,” goes the famous adage.

- Imagine the sight of a beloved family cat who has been struck by a car on the highway.

- When I was a child, our family cat loved to roam free in the neighbourhood. I never wondered why there were no birds in our backyard, like my friends enjoyed and experienced.

Appeal:

- Beginning with a provocative question or opinion

- Opening with a striking image

- Presenting an explanation or rationalization for your essay

- Opening with a startling statistic or surprising fact

- Including a personal anecdote

- Raising a question or series of questions

- Appealing to their emotions

- Opening with a relevant quotation or incident

- Using logic

Answer Key

- G

- I

- A

- D

- F

- C

- H

- B

- E

Writing a Conclusion

It is not unusual to want to rush when you approach your conclusion, and even experienced writers may fade by the time they get to the end. But what good writers remember is that it is vital to put just as much attention into the conclusion as the rest of the essay. After all, a hasty ending can undermine an otherwise strong essay.

A conclusion that does not correspond to the rest of your essay, has loose ends, or is unorganized can unsettle your readers and raise doubts about the entire essay. However, if you have worked hard to write the introduction and body, your conclusion can often be the most logical part to compose.

The Anatomy of a Strong Conclusion

Keep in mind that the ideas in your conclusion must conform to the rest of your essay. In order to tie these components together, restate your thesis at the beginning of your conclusion. This helps you assemble, in an orderly fashion, all the information you have explained in the body. Repeating your thesis reminds your readers of the major arguments you have been trying to prove and also indicates that your essay is drawing to a close. A strong conclusion also reviews your main points and emphasizes the importance of the topic.

The construction of the conclusion is similar to the introduction, in which you make general introductory statements and then present your thesis. The difference is that in the conclusion you first paraphrase, or state in different words, your thesis and then follow up with general concluding remarks. These sentences should progressively broaden the focus of your thesis and manoeuvre your readers out of the essay.

Many writers like to end their essays with a final emphatic statement. This strong closing statement will cause your readers to continue thinking about the implications of your essay; it will make your conclusion, and thus your essay, more memorable. Another powerful technique is to challenge your readers to make a change in either their thoughts or their actions. Challenging your readers to see the subject through new eyes is a powerful way to ease yourself and your readers out of the essay.

Tip: Avoid doing any of the following in your conclusion:

- Introducing new material

- Contradicting your thesis

- Changing your thesis

- Using apologies or disclaimers

Introducing new material in your conclusion has an unsettling effect on your reader. When you raise new points, you make your reader want more information, which you could not possibly provide in the limited space of your final paragraph.

Contradicting or changing your thesis statement causes your readers to think that you do not actually have a conviction about your topic. After all, you have spent several paragraphs adhering to a singular point of view. When you change sides or open up your point of view in the conclusion, your reader becomes less inclined to believe your original argument.

By apologizing for your opinion or stating that you know it is tough to digest, you are in fact admitting that even you know what you have discussed is irrelevant or unconvincing. You do not want your readers to feel this way. Effective writers stand by their thesis statement and do not stray from it.

Self-Practice Exercise 7.9

H5P: Drafting Introduction and Conclusion

Introduction

In this exercise, we will apply what we have learned about Introductions and Conclusions in order to draft both for your essay. It’s okay if you don’t think this will be the final, perfect version of either — you have lots of time to revise. The goal here is to practice your skills and understanding while it’s fresh in your mind.

- Identify one or two strategies for attracting attention to your essay, and draft sentences using them.

- The other job of an introduction is to make sure your reader has a sense of how they essay will develop. Draft a sentence of two that gestures to how you will prove your thesis statement.

- Restate your thesis statement.

- Combine all of what you’ve done so far into an introductory paragraph.

Conclusion

- Start by restating your thesis in different words using your paraphrasing skills.

- Make note of any concluding remarks you would like to include. Remember: these sentences should progressively broaden the focus of your thesis and manoeuvre your readers out of the essay. Look at Mariah’s example again if you want guidance.

- Come up with a final, emphatic statement for your essay. A good way to structure this is to articulate in one sentence why the topic of your essay matters, and why you care about it.

- Combine all of what you’ve done so far into a concluding paragraph.