Chapter 11: Revising Your Work

Reverse Outlining

Often, outlining is recommended as an early component of the writing process as a way to organize and connect thoughts so the shape of what you are going to write is clear before you start drafting it. This is a tool many writers use that is probably already familiar to you.

Reverse outlining, though, is different in a few ways. First, it happens later in the process, after a draft is completed rather than before. Second, it gives you an opportunity to review and assess the ideas and connections that are actually present in the completed draft. This is almost an opposite approach from traditional outlining, which considers an initial set of ideas that might shift as the draft is written and new ideas are added or existing ones are moved, changed, or removed entirely. A reverse outline can help you improve the structure and organization of your already-written draft, letting you see where support is missing for a specific point or where ideas don’t quite connect on the page as clearly as you wanted them to.

How to Create a Reverse Outline

- At the top of a fresh sheet of paper, write your primary purpose for the text you want to outline. This should be the purpose exactly as it appears in your draft, not the purpose you know you intended. If you can’t find the actual words, write down that you can’t find them in this draft of the message—it’s an important note to make!

- Draw a line down the middle of the page, creating two columns below your message purpose.

- Read, preferably out loud, the first body paragraph of your draft.

- In the left column, write the single main idea of that paragraph (again, this should be using only the words that are actually on the page, not the ones you want to be on the page). If you find more than one main idea in a paragraph, write down all of them. If you can’t find a main idea, write that down, too.

- In the right column, state how the main idea of that paragraph supports the purpose.

- Repeat steps 3-5 for each body paragraph of the draft.

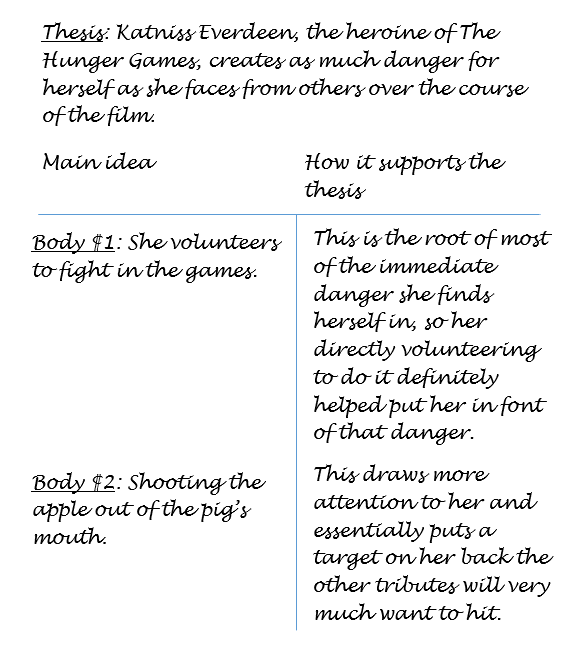

Once you have completed these steps, you have a reverse outline! It might look a little something like the reverse outline shown below.

Working with the Results of your Reverse Outline

Now what? You’ve probably already made some observations while completing this. Do you notice places where you are repeating yourself in your message? Do you notice places where some of your paragraphs have too many points or don’t clearly support the purpose of the message?

There are a number of observations that can be made with the aid of a reverse outline, and a number of ways it can help you strengthen your messages.

If multiple paragraphs share the same idea

You might try combining them, reducing the information for that idea so your paper doesn’t feel imbalanced, and/or organizing these paragraphs about the same point so they are next to each other in the paper.

If any paragraphs have multiple main ideas

Each paragraph should have only one primary focus. If you notice a paragraph does have more than one main idea, you could look for where some of those ideas might be discussed in other paragraphs and move them into a paragraph already focusing on that point. You could also select just the one main idea you think is most important to this paragraph and cut the other points out. Another option would be to split that paragraph into multiple paragraphs and expand on each main idea.

If any paragraph lacks a clear main idea

If it was hard for you to find the main idea of a paragraph, it will also be hard for your reader to find. For paragraphs that don’t yet have a main idea, consider whether the information in that paragraph points to a main idea that just isn’t written on the page yet. If the information does all support one main idea, adding that idea to the paragraph might be all that is needed. Alternatively, you may find that some of the ideas fit into other paragraphs to support their ideas, or you may not need some of them in the next draft at all.

If any ideas don’t connect well to the purpose of the message

It should be clear how the main idea of each paragraph supports the purpose of the message. If that connection is not clear, ask yourself how the main idea of that paragraph does further your purpose and then write that response.

If there are gaps in reasoning

If a message starts out introducing something that is a problem in a community, then presents a solution to the problem, and then talks about why the problem is a problem, this organization is likely to confuse readers. Reorganizing to introduce the problem, discuss why it is a problem, and then move on to proposing a solution would do good work to help strengthen the next draft of this paper. If there are gaps in reasoning, you may need to move, revise, or add transition statements after moving paragraphs around.