Chapter 2: Researching With Integrity

Referencing Other’s Work

What is Referencing?

Imagine that you’ve just arrived for a meeting about a group project. You and your friend are early, so you chat about the project.

“I think we should do our project about caring for aging parents,” you say. Your friend tells you this is a great idea.

The rest of your group members arrive, and you begin to brainstorm ideas for your project. Before you can share your idea, your friend speaks up.

“I’ve been thinking that we should do our project on how to care for aging parents,” they say.

Everyone thinks it’s a great idea and they compliment your friend.

If this happened to you, how would you feel? Probably, you would feel angry that your friend passed your idea off as their own, even if they didn’t use your exact words. Would you feel differently if the friend had told the group that it was your idea? Probably, right?

Referencing, also known as citing, is giving credit. This is done with your in-text citations and reference page. If your sources are well-cited, you’ve told the audience whose ideas/words belong to whom and exactly where to go to find those words.

Think of referencing as a way of saying thank you. Lots of scholars, like Jesse Stommel and Pete Rorabaugh, say that it’s easier to understand citation when you think of it as saying thank you to those who have given you great ideas. In a blog post, Stommel says no one has truly original ideas, but that we should practice “citation, generosity, connection, and collaboration” to work with sources ethically. [1] .

Why Cite Sources?

There are many good reasons to cite sources.

To Avoid Plagiarism & Maintain Academic Integrity

Misrepresenting your academic achievements by not giving credit to others indicates a lack of academic integrity. This is not only looked down upon by the scholarly community, but it is also punished. When you are a student this could mean a failing grade or even expulsion from college.

To Acknowledge the Work of Others

One major purpose of citations is to simply provide credit where it is due. When you provide accurate citations, you are acknowledging both the hard work that has gone into producing research and the person(s) who performed that research.

To Provide Credibility to Your Work & to Place Your Work in Context

Providing accurate citations puts your work and ideas into an academic context. They tell your reader that you’ve done your research and know what others have said about your topic. Not only do citations provide context for your work but they also lend credibility and authority to your claims.

To Help Your Future Researching Self & Other Researchers Easily Locate Sources

Having accurate citations will help you as a researcher and writer keep track of the sources and information you find so that you can easily find the source again. Accurate citations may take some effort to produce, but they will save you time in the long run. So think of proper citation as a gift to your future researching self!

Ethical Citation Beyond Giving Credit

Citation is also a time to think about what kind of sources you value and who you cite. One way to ensure that you have a thorough view of the issue is to look intentionally for scholars from diverse backgrounds and perspectives. Sometimes, when you’re busy, it’s easy to reach for the first few sources that pop up in the database. But if all of these scholars are of the same demographic, (for example, if they’re all white males between 45 and 60), you’re likely missing an important perspective. Being intentional about who you cite will help you do more thorough analysis.

Challenges in Referencing

Besides the clarifications and difficulties around citing that we have already considered, there are additional challenges that might make knowing when and how to cite difficult for you.

You Learned How to Write In A Different School System.

Citation practices are not universal. Different countries and cultures approach using sources in different ways. If you’re new to the Canadian school system, you might have learned a different way of citing. For example, some countries have a more communal approach to sources. Others see school as “not real life,” so you don’t need to cite sources in the same way that you would on the job.

Not Really Understanding the Material You’re Using

If you are working in a new field or subject area, you might have difficulty understanding the information from other scholars, thus making it difficult to know how to paraphrase or summarize that work properly. It can be tempting to change just one or two words in a sentence, but this is still plagiarism.

Running Out of Time

When you are a student taking many classes, working and/or taking care of family members, it may be hard to devote the time needed to doing good scholarship and accurately representing the sources you have used. Research takes time. The sooner you can start and the more time you can devote to it, the better your work will be.

When to Cite Sources

Citation and source use are all about balance. If you don’t use enough sources, you might struggle to make a thorough argument. If you cite too much, you won’t leave room for your own voice in your writing.

To illustrate this point, think of a lawyer arguing a case in a trial. If the lawyer just talks to the jury and doesn’t call any witnesses, they probably won’t win the case. After all, a lawyer isn’t an expert in forensics or accident reconstruction or Internet fraud. The lawyer also wasn’t there when the incident occurred. That’s where witnesses come in. The witnesses have knowledge that the lawyer doesn’t.

But if the lawyer just lets the witnesses talk and sits there quietly, they’ll likely also lose the case. That’s because the lawyer is the one who’s making the overall argument. The lawyer asks the witnesses questions and shows how the testimony of different witnesses piece together to prove the case.

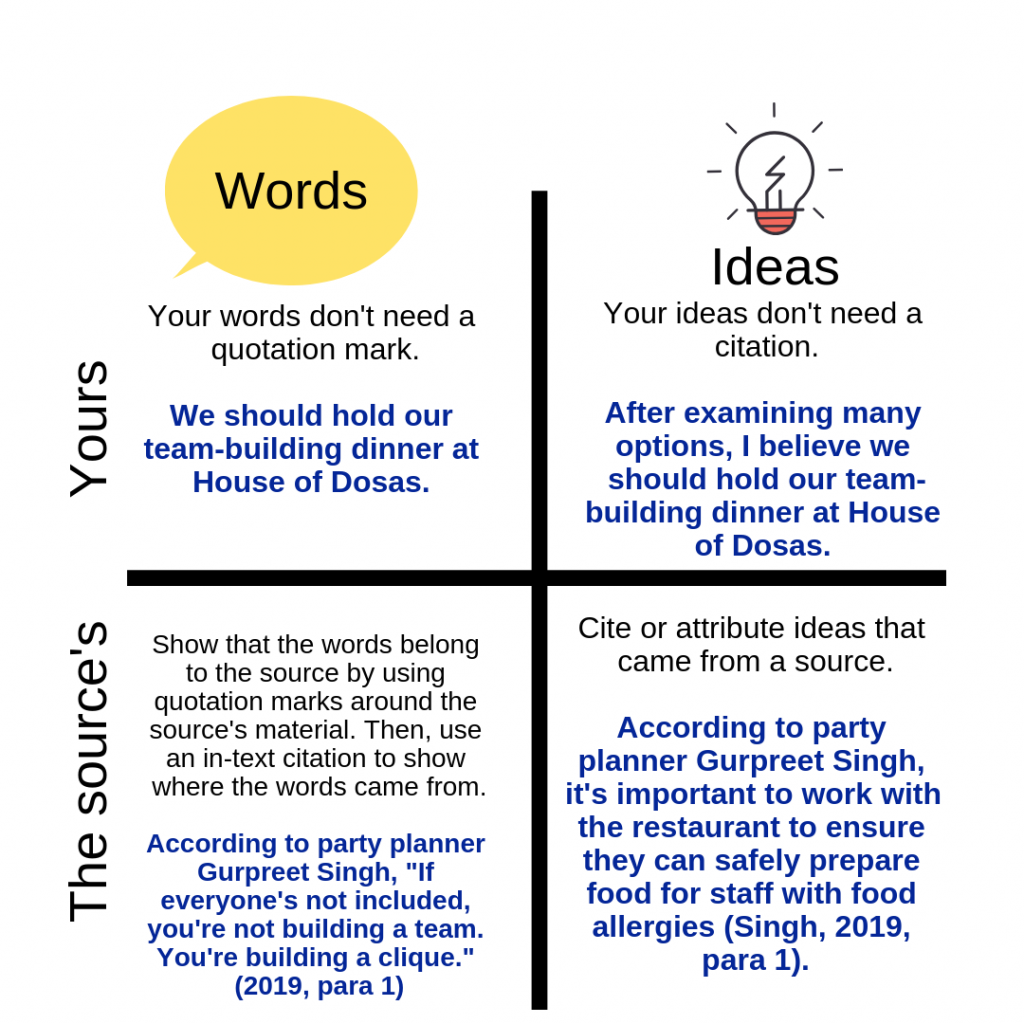

To cite sources, you should make two things clear:

- The difference between your words and the source’s words.

- The difference between your ideas and the source’s ideas.

This diagram illustrates the difference:

Attributing A Source’s Words

When you quote someone in your document, you’re basically passing the microphone to them. Inviting another voice into your piece means that the way that person said something is important. Maybe that person is an expert and their words are a persuasive piece of evidence. Maybe you’re using the words as an example. Either way, you’ll likely do some sort of analysis on the quote.

When you use the source’s words, put quotation marks around them. This creates a visual separation between what you say and what your source says. You also don’t just want to drop the quote into the document with no explanation. Instead, you should build a “frame” around the quote by explaining who said it and why it’s important. In short, you surround the other person’s voice with your own voice.

Tip: The longer the source, the more analysis you’re likely going to do.

Here’s an example of a way to integrate a quote within a paragraph.

According to Haudenosaunee writer Alicia Elliot, “We know our cultures have meaning and worth, and that culture lives and breathes inside our languages.” (Elliot, 2019) Here, Elliot shows that when Indigenous people have the opportunity to learn Indigenous languages, which for generations were intentionally suppressed by the Canadian government, they can connect with their culture in a new way.

As you can see, Elliot’s words are important. If you tried to paraphrase them, you’d lose the meaning. Elliot is also a well-known writer, so adding her voice into the document adds credibility. If you’re writing about Indigenous people, it’s also important to include the voices of Indigenous people in your work.

You can see that in this example, the author doesn’t just pass the microphone to Alicia Elliot. Instead, they surround the quote with their own words (bolded), explaining who said the quote and why it’s important.

Attributing the Source’s Ideas

When the source’s ideas are important, you’ll want to paraphrase or summarize. For example, Elliot goes on to say that when over half of Indigenous people in a community speak an Indigenous language, the suicide rate goes down (Elliot, 2019). Here, it’s the idea that’s important, not the words, so you should paraphrase it.

What is paraphrasing? Paraphrasing is when you restate an idea in your own words. It’s this last bit — the “own words” part – that is confusing. What counts as your own words?

When you’re paraphrasing, you should ask yourself, “Have I restated this in a way that shows that I understand it?” If you simply swap out a few words for synonyms, you haven’t shown that you understand the idea. For example, let’s go back to that Alicia Elliot quote: “We know our cultures have meaning and worth, and that culture lives and breathes inside our languages.” What if I swapped out a few words so it said “We know our cultures have value and importance, and that culture lives and exhales inside our languages.”?

Does this show that I understand the quote? No. Elliot composed that line with a lot of precision and thoughtfulness. Switching a few words around actually shows disrespect for the care she took with her language.

Instead, paraphrase by not looking at the source material. Put down the book or turn off your computer monitor, then describe the idea back as if you were speaking to a friend.

Here’s another example from Alicia Elliot’s book A Mind Spread Out On the Ground. See if you can paraphrase it. First, read the quote:

Before you paraphrase it, think about what it means to you. Maybe you’ve had the experience of learning the slang or curse words in a new language and finding out what that culture sees as valuable or taboo. Maybe you’ve felt frustrated by not being able to make yourself clear in a different language. Maybe you’ve had to translate for a friend or family member, and haven’t been able to exactly capture what was said.

Now, pretend that someone asked you what Alicia Elliot said. How would you describe it?

Maybe you wrote, “According to Alicia Elliot, it’s hard to translate from one language to another because a language is about so much more than just the words on a page.” Maybe you wrote, “According to Alicia Elliot, knowing another language shows how other people see the world.” Paraphrasing this way not only helps you analyze the quote, but also gives Alicia Elliot credit for her ideas.

What’s the Difference Between Paraphrasing and Summarizing?

When you paraphrase, you take a single point within a source and restate it. What you did above is paraphrasing. Usually, the paraphrased version is about the same length as the original source. The goal of paraphrasing is usually to take someone else’s idea and restate it so that it fits the tone of whatever you’re writing. For example, you might take a complicated sentence from an academic journal and restate it so that your classmates could more easily understand it.

When you summarize, you are simply trying to capture the main points of a larger source in a short way. Your summary will be shorter than the original source. For example, an abstract summarizes the contents of an entire report or article. You might read a book and summarize it by telling friends the main points.

What Information Do I Cite?

Citing sources is often depicted as a straightforward, rule-based practice. In fact, there are many grey areas around citation, and learning how to apply citation guidelines takes practice and education. If you are confused by it, you are not alone – in fact you might be doing some good thinking. Here are some guidelines to help you navigate citation practices.

Cite when you are directly quoting. This is the easiest rule to understand. If you are stating word for word what someone else has already written, you must put quotes around those words and you must give credit to the original author. Not doing so would mean that you are letting your reader believe these words are your own and represent your own effort.

Cite when you are summarizing and paraphrasing. This is a trickier area to understand. First of all, summarizing and paraphrasing are two related practices but they are not the same. Again, summarizing is when you read a text, consider the main points, and provide a shorter version of what you learned. Paraphrasing is when you restate what the original author said in your own words and in your own tone. Both summarizing and paraphrasing require good writing skills and an accurate understanding of the material you are trying to convey. Summarizing and paraphrasing are not easy to do when you are a beginning academic researcher, but these skills become easier to perform over time with practice.

Cite when you are citing something that is highly debatable. For example, if you want to claim that an oil pipeline is necessary for economic development, you will have to contend with those who say that it produces few jobs and has a high risk of causing an oil spill that would be devastating to wildlife and tourism. To do so, you’ll need experts on your side.

When Don’t You Cite?

Don’t cite when what you are saying is your own insight. Research involves forming opinions and insights around what you learn. You may be citing several sources that have helped you learn, but at some point you are integrating your own opinion, conclusion, or insight into the work. The fact that you are NOT citing it helps the reader understand that this portion of the work is your unique contribution developed through your own research efforts.

Don’t cite when you are stating common knowledge. What is common knowledge is sometimes difficult to discern. Generally quick facts like historical dates or events are not cited because they are common knowledge.

Examples of information that would not need to be cited include:

- Partition in India happened on August 15th, 1947.

- Vancouver is the 8th biggest city in Canada.

Some quick facts, such as statistics, are trickier. For example, the number of gun- related deaths per year probably should be cited, because there are a lot of ways this number could be determined (does the number include murder only, or suicides and accidents, as well?) and there might be different numbers provided by different organizations, each with an agenda around gun laws.

A guideline that can help with determining whether or not to cite facts is to determine whether the same data is repeated in multiple sources. If it is not, it is best to cite.

The other thing that makes this determination difficult might be that what seems new and insightful to you might be common knowledge to an expert in the field. You have to use your best judgment, and probably err on the side of over-citing, as you are learning to do academic research. You can seek the advice of your instructor, a writing tutor, or a librarian. Knowing what is and is not common knowledge is a practiced skill that gets easier with time and with your own increased knowledge.

When to Cite

Any idea or fact taken from an outside source must be cited, in both the body of your paper and the references. The only exceptions are facts or general statements that are common knowledge. Common knowledge facts or general statements are commonly supported by and found in multiple sources. For example, a writer would not need to cite the statement that most breads, pastas, and cereals are high in carbohydrates; this is well known and well documented. However, if a writer explained in detail the differences among the chemical structures of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, a citation would be necessary. When in doubt, cite!

H5P: To Cite or Not to Cite

For each example of a piece of evidence, state whether you need to cite or not cite the original source.

- A general fact about the periodic table you found in an encyclopedia

- do need to cite

- don’t need to cite

- A brief summary of a study you read, written in your own words

- do need to cite

- don’t need to cite

- The dictionary definition of a key term

- do need to cite

- don’t need to cite

- A paraphrase of an idea in one of your source articles

- do need to cite

- don’t need to cite

Answer Key

- B

- A

- B

- A

Image Description

Figure 2.1 image description: This chart illustrates the concept that you should use quotation marks and in-text citation to distinguish between the words of the source and your own words. Your words don’t need a quotation mark – We should hold our team-building dinner at House of Dosas. The source’s words do need a quotation mark. Show that the words belong to the source by using quotation marks around the source’s material. Then, use an in-text citation to show where the words come from. According to party planner Gurpreet Singh, “If everyone’s not included, you’re not building a team. You’re building a clique.” (Singh, 2019) Your ideas do not need a citation – After examining many options, I believe we should hold our team-building dinner at House of Dosas. Cite or attribute ideas that came from a source – According to party planner Gurpreet Singh, it’s importnat to work with the restaurant to ensure they can safely prepare food for staff with food allergies (Singh, 2019). [Return to Figure 2.1]

- https://hybridpedagogy.org/the-four-noble-virtues-of-digital-media-citation/ ↵