Social and emotional challenges and opportunities

Learning Objectives

- Investigate the possible causes of concerning behaviours in adolescence using theories of development, attachment and knowledge of mental health and wellness.

- Examine evidence based interventions aimed at increasing effective, prosocial and emotional coping strategies.

Introduction

Our readings have focused on the physical, cognitive, social, and emotional development including milestones, risk and protective factors present, the various systems that surround an adolescent, expectations, and exceptionalities that make up an individual’s adolescent years. In examining all of these biological, social, psychological, and environmental circumstances, we can further our understanding as Child and Youth Care Practitioners (CYCPs). In our relationships, interactions, activities and interventions, we can use this information to formulate how to best support and encourage healthy development for adolescents.

Incorporating all our learning regarding child development in our previous semester along with our knowledge and understanding of how development shapes an individual during adolescence, in this reading we explore how these elements come together. We will review potential challenges and how to support young people and their families. This reading describes how to bring everything together and address potential challenges and opportunities. This week’s reading explores some of the challenges (part 1) and next week will explore opportunities (part 2).

Factors impacting development in adolescence

Understanding the concerns that can exist for adolescents is essential for a CYCP. Knowing what to expect, what to look for, and what the needs of an individual may be all come together to shape how we support goals and progress, and incorporate various interventions. Getting to know an adolescent involves using the information available to us and adapting our approach to be inclusive, utilize strengths, and be familiar with evidence-based strategies to best support their needs. Regardless of what their needs may be, we use this knowledge to individualize our approach and support healthy development.

In your mental health courses, you have covered a variety of mental health concerns relating to children and youth. As this course focuses on development, you are encouraged to review your notes and readings from those courses to refresh your memory; this will be a short summary stemming from your previous learning.

Sibling Relationships

Siblings spend a considerable amount of time with each other and offer a unique relationship that is not found with same-age peers or with adults. Siblings play an important role in the development of social skills. Cooperative and pretend play interactions between younger and older siblings can teach empathy, sharing, and cooperation (Pike, Coldwell, & Dunn, 2005), as well as negotiation and conflict resolution (Abuhatoum & Howe, 2013). However, the quality of sibling relationships is often mediated by the quality of the parent-child relationship and the psychological adjustment of the child (Pike et al., 2005). For instance, more negative interactions between siblings have been reported in families where parents had poor patterns of communication with their children (Brody, Stoneman, & McCoy, 1994). Children who have emotional and behavioral problems are also more likely to have negative interactions with their siblings. However, the psychological adjustment of the child can sometimes be a reflection of the parent-child relationship. Thus, when examining the quality of sibling interactions, it is often difficult to tease out the separate effect of adjustment from the effect of the parent-child relationship.

While parents want positive interactions between their children, conflicts are going to arise, and some confrontations can be the impetus for growth in children’s social and cognitive skills. The sources of conflict between siblings often depend on their respective ages. Dunn and Munn (1987) revealed that over half of all sibling conflicts in early childhood were disputes about property rights. By middle childhood, this starts shifting toward control over social situations, such as what games to play, disagreements about facts or opinions, or rude behavior (Howe, Rinaldi, Jennings, & Petrakos, 2002). Researchers have also found that the strategies children use to deal with conflict change with age, but that this is also tempered by the nature of the conflict. Abuhatoum and Howe (2013) found that coercive strategies (e.g., threats) were preferred when the dispute centered on property rights, while reasoning was more likely to be used by older siblings and in disputes regarding control over the social situation. However, younger siblings also use reasoning, frequently bringing up the concern of legitimacy (e.g., “You’re not the boss”) when in conflict with an older sibling. This strategy is commonly used by younger siblings and is possibly an adaptive strategy in order for younger siblings to assert their autonomy (Abuhatoum & Howe, 2013). A number of researchers have found that children who can use non-coercive strategies are more likely to have a successful resolution, whereby a compromise is reached, and neither child feels slighted (Ram & Ross, 2008; Abuhatoum & Howe, 2013).

Not surprisingly, friendly relationships with siblings often lead to more positive interactions with peers. The reverse is also true. A child can also learn to get along with a sibling, with, as the song says, “a little help from my friends” (Kramer & Gottman, 1992).

In late adolescence, as teens become more independent, research has shown a decline in the frequency of interactions between siblings, as presumably peers and romantic relationships become more central to the lives of young people. Aquilino (2006) suggests that during this transition, the task may be to maintain enough of a sibling bond so that there will be a foundation for this relationship in later life. Those who are successful can often move away from the “older-younger” sibling conflicts of childhood, toward an equal relationship between two adults. Siblings that were close to each other in childhood are typically close in adulthood (Dunn, 1984, 2007), and in fact, it is unusual for siblings to develop closeness for the first time in adulthood. Overall, the majority of adult sibling relationships are close (Cicirelli, 2009).

Peer relationships

Peers can serve both positive and negative functions during adolescence. Negative peer pressure can lead adolescents to make riskier decisions or engage in more problematic behavior than they would alone or in the presence of their family. For example, adolescents are much more likely to drink alcohol, use drugs, and commit crimes when they are with their friends than when they are alone or with their family. However, peers also serve as an important source of social support and companionship during adolescence, and adolescents with positive peer relationships are happier and better adjusted than those who are socially isolated or who have conflictual peer relationships. Crowds are an emerging level of peer relationships in adolescence. In contrast to friendships (which are reciprocal dyadic relationships) and cliques (which refer to groups of individuals who interact frequently), crowds are characterized more by shared reputations or images than actual interactions (Brown & Larson, 2009) These crowds reflect different prototypic identities (such as jocks or brains) and are often linked with adolescents’ social status and peers’ perceptions of their values or behaviors.

Conflict over how much time is spent with each other versus with friends, jealousies stemming from too much time spent with a friend of the opposite sex, and new romantic possibilities are all part of the social fabric of adolescence. Although “normal” from a developmental perspective, navigating such issues can cause conflict and, for some adolescents, lead to aggressive responses and problematic coping strategies, such as stalking, psychological or verbal abuse, and efforts to gain control.

Violence, abuse, and neglect

Violence and abuse are among the most disconcerting of the challenges that today’s families face. Abuse can occur between spouses, between parent and child, as well as between other family members. The frequency of violence among families is difficult to determine because many cases of spousal abuse and child abuse go unreported. In any case, studies have shown that abuse (reported or not) has a major impact on families and society as a whole, and on the individual in the form of development: physical, psychological, behavioural, academic, interpersonal, and self-perceptual (Fallon et al., 2021).

Children and teens are among the most helpless victims of abuse and neglect. In 2021-2022, there were more than 114,000 calls and referrals to one of Ontario’s 50 Children’s Aid Societies (Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies, 2022). Of these cases, 61,000 led to a full investigation, while the rest were either not investigated, or resulted in referrals to community resources (Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies, 2022). In that same timeframe, there was a monthly average of 8,600 kids in care in Ontario, 60% of those were 16 years or older (Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies, 2022).

Developmental models focus on interpersonal contexts in both childhood and adolescence that foster depression and anxiety (e.g., Rudolph, 2009). Family adversity, such as abuse and parental psychopathology, during childhood sets the stage for social and behavioural concerns during adolescence. Adolescents with such concerns generate stress in their relationships (e.g., by resolving conflict poorly and excessively seeking reassurance) and select into more maladaptive social contexts (e.g., “misery loves company” scenarios in which depressed youths select other depressed youths as friends and then frequently co-ruminate as they discuss their problems, exacerbating negative affect and stress). These processes are intensified for girls compared with boys because girls have more relationship-oriented goals related to intimacy and social approval, leaving them more vulnerable to disruption in these relationships. Anxiety and depression then exacerbate problems in social relationships, which in turn contribute to the stability of anxiety and depression over time.

Anxiety and Depression

Developmental models of anxiety and depression also treat adolescence as an important period, especially in terms of the emergence of gender differences in prevalence rates that persist through adulthood (Rudolph, 2009). Starting in early adolescence, compared with males, females have rates of anxiety that are about twice as high and rates of depression that are 1.5 to 3 times as high (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) Although the rates vary across specific anxiety and depression diagnoses, rates for some disorders are markedly higher in adolescence than in childhood or adulthood. For example, prevalence rates for specific phobias are about 5% in children and 3%–5% in adults but 16% in adolescents. Additionally, some adolescents sink into major depression, a deep sadness and hopelessness that disrupts all normal, regular activities. Causes include many factors such as genetics and early childhood experiences that predate adolescence, but puberty may push vulnerable children, especially girls into despair.

During puberty, the rate of major depression more than doubles to an estimated 15%, affecting about one in five girls and one in ten boys. The gender difference occurs for many reasons, biological and cultural (Uddin et al., 2010, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019) Anxiety and depression are particularly concerning because suicide is one of the leading causes of death during adolescence. Some adolescents experience suicidal ideation (distressing thoughts about killing oneself) which become most common at about age 15 (Berger, 2019, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019) and can lead to parasuicide, also called attempted suicide or failed suicide. Suicidal ideation and parasuicide should be taken seriously and serve as a warning that emotions may be overwhelming.

Family changes: Divorce

Much attention has been given to the impact of divorce on the life of young people. The assumption has been that divorce has a strong, negative impact on the child and that single-parent families are deficient in some way. However, the research suggests that 75 to 80 percent of children and adults who experience divorce suffer no long term effects (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). Children of divorce and children who have not experienced divorce are more similar than different (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019).

Mintz (2004) suggests that the alarmist view of divorce was due in part to the newness of divorce when rates in the United States began to climb in the late 1970s. Adults reacting to the change grew up in the 1950s when rates were low. As divorce has become more common, and there is less stigma associated with divorce, this view has changed somewhat. Social scientists have operated from divorce as a deficit model emphasizing the problems of being from a “broken home” (Seccombe &Warner, 2004, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). More recently, a more objective view of divorce, re-partnering, and remarriage indicate that divorce, remarriage, and life in stepfamilies can have a variety of effects. The exaggeration of the negative consequences of divorce has left the majority of those who do well hidden and subjected them to unnecessary stigma and social disapproval (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019).

The tasks of families listed above are functions that can be fulfilled in a variety of family types-not just intact, two-parent households. Harmony and stability can be achieved in many family forms and when it is disrupted, either through divorce, or efforts to blend families, or any other circumstances, the child suffers (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019).

Factors Affecting the Impact of Divorce

Some negative consequences are a result of financial hardship rather than divorce per se (Drexler, 2005, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). Some positive consequences reflect improvements in meeting these functions. For instance, we have learned that positive self-esteem comes in part from a belief in the self and one’s abilities rather than merely being complimented by others. In single-parent homes, children may be given more opportunity to discover their abilities and gain the independence that fosters self-esteem. If divorce leads to fighting between the parents and the child is included in these arguments, the self-esteem may suffer.

The impact of divorce on children depends on several factors. The degree of conflict before divorce plays a role. If the divorce means a reduction in tensions, the child may feel relief. If the parents have kept their conflicts hidden, the announcement of a divorce can come as a shock and be met with enormous resentment. Another factor that has a significant impact on the child concerns financial hardships they may suffer, especially if financial support is inadequate. Another difficult situation for children of divorce is the position they are put into if the parents continue to argue and fight-especially if they bring the children into those arguments.

Short-term consequences: In roughly the first year following divorce, children may exhibit some of these short-term effects:

- Grief over losses suffered. The child will grieve the loss of the parent they no longer see as frequently. The child may also grieve about other family members that are no longer available. Grief sometimes comes in the form of sadness, but it can also be experienced as anger or withdrawal. Preschool-aged boys may act out aggressively while the same-aged girls may become more quiet and withdrawn. Older children may feel depressed.

- Reduced Standard of Living. Very often, divorce means a change in the amount of money coming into the household. Children experience in new constraints on spending or entertainment. School-aged children, especially, may notice that they can no longer have toys, clothing, or other items to which they have grown accustomed, or it may mean that there is less eating out or canceling satellite television, and so on. The custodial parent may experience stress at not being able to rely on child support payments or having the same level of income as before. This uncertainty can affect decisions regarding healthcare, vacations, rents, mortgages, and other expenditures. The stress can result in less happiness and relaxation in the home. The parent who has to take on more work may also be less available to the children.

- Adjusting to Transitions. Children may also have to adjust to other changes accompanying a divorce. The divorce might mean moving to a new home and changing schools or friends. It might mean leaving a neighborhood that has meant a lot to them as well.

Long-Term consequences: The following are some effects found after the first year of a divorce:

- Economic/Occupational Status. One of the most commonly cited long-term effects of divorce is that children of divorce may have lower levels of education or occupational status. This finding may be a consequence of lower-income and resources for funding education rather than to divorce per se. In those households where economic hardship does not occur, there may be no impact on education or occupational status (Drexler, 2005, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019).

- Improved Relationships with the Custodial Parent (usually the mother): The majority of custodial parents are mothers (approximately 80.4 percent) and

19.6 percent of custodial parents are fathers. Shared custody is on the rise, however, and shows promising social, academic, and psychological results for the children. Children from single-parent families talk to their mothers more often than children of two-parent families (McLanahan and Sandefur, 1994, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). Most children of divorce lead happy, well-adjusted lives and develop stronger, positive relationships with their custodial parent (Seccombe and Warner, 2004, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). In a study of college-age respondents, Arditti (1999) found that increasing closeness and a movement toward more democratic parenting styles was experienced. Others have also found that relationships between mothers and children become closer and stronger (Guttman, 1993) and suggest that greater equality and less rigid parenting is beneficial after divorce (Steward, Copeland, Chester, Malley, and Barenbaum, 1997). - Greater emotional independence in sons. Drexler (2005) notes that sons who are raised by mothers only develop an emotional sensitivity to others that is beneficial in relationships.

- Feeling more anxious in their own love relationships. Children of divorce may feel more anxious about their relationships as adults. This anxiety may reflect a fear of divorce if things go wrong, or it may be a result of setting higher expectations for their relationships.

- Adjustment of the custodial parent. Furstenberg and Cherlin (1991, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019) believe that the primary factor influencing the way that children adjust to divorce is the way the custodial parent adjusts to the divorce. If that parent is adjusting well, the children will benefit. This factor may explain a good deal of the variation we find in children of divorce. Adults going through a divorce should consider good self-care as beneficial to the children-not as self-indulgent.

- Mental health issues: Some studies suggest that anxiety and depression that are common in children and adults within the first year of divorce may not resolve. A 15-year study by Bohman, Låftman, Päären, Jonsson (2017, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019) suggests that parental separation significantly increases the risk for depression 15 years later when depression rates were compared to matched controls. In fact, the risk of depression was related more strongly with parental conflict and parental separation than it was with parental depression!

Concerning behaviours in adolescence

Bullying Behaviour

Bullying is unwanted, aggressive behaviour among young people that involves a real or perceived power imbalance. The behaviour is repeated, or has the potential to be repeated, over time. Both kids who are bullied and who bully others may have serious, lasting problems. While this typically takes place during middle young personhood, these behaviours continue into adolescence.

In order to be considered bullying, the behaviour must be aggressive and include:

- An Imbalance of Power: Kids who bully use their power—such as physical strength, access to embarrassing information, or popularity—to control or harm others. Power imbalances can change over time and in different situations, even if they involve the same people.

- Repetition: Bullying behaviours happen more than once or have the potential to happen more than once.

Bullying includes actions, such as making threats, spreading rumors, attacking someone physically or verbally, and excluding someone from a group on purpose. Bullying is not peer conflict, dating violence, hazing, gang violence, harassment (legal definition), or stalking. While these issues may also be problematic, they do not meet the criteria for bullying behaviour.

Types of bullying behaviour

There are several types of bullying, and it is not unusual for a bully to utilize more than one type. Verbal bullying is saying, or writing mean things and may include behaviours like teasing or name-calling, inappropriate sexual comments, taunting, and threatening to cause harm. Social bullying is sometimes referred to as relational bullying. It involves behaviours such as hurting someone’s reputation or relationships by purposely excluding them or getting others to exclude them, spreading rumors about someone, or embarrassing someone in public. This can also include cyberbullying which includes harassment, intimidation, threatening emails, text messages, social media posts, and other forms of digital and electronic communication to bully another person (PREVNet.ca, 2023). Physical bullying is hurting a person’s body or possessions by hitting, kicking, or pinching, spitting, tripping or pushing, taking or breaking someone’s things, or making mean or rude hand gestures.

The roles in bullying behaviour

There are many roles that individuals may take in bullying situations. Kids can bully others, they can be bullied, or they may witness bullying. Some may play more than one role, sometimes being both bullied and the bully. It is important to understand the multiple roles involved in these situations in order to prevent and respond to bullying effectively.

Importance of not labeling kids

When referring to a bullying situation, it is easy to call the kids who bully others “bullies” and those who are targeted “victims,” but this may have unintended consequences. When young person are labeled as “bullies” or “victims,” it may send the message that the individual’s behaviour cannot change. It also fails to recognize the multiple roles one might play in different bullying situations. Labeling also disregards other factors contributing to the behaviour such as peer influence or school climate.

Instead of labeling the teens involved, focus on the behaviour. For instance, instead of calling someone a “bully,” refer to them as “the person who bullied.” Instead of calling a person a “victim,” refer to them as “the person who was bullied.”

The role of the bully

The roles individuals play in bullying are not limited to those who bully others and those who are bullied. Some researchers talk about the “circle of bullying” to define both those directly involved in bullying and those who actively or passively assist the behaviour or defend against it. Direct roles include:

- Those who Bully: These teens engage in bullying behaviour towards their peers. There are many risk factors that may contribute to their involvement in the behaviour. Often, these kids require support to change their behaviour and address any other challenges that may be influencing their behaviour.

- Those who are Bullied: These teens are the targets of bullying behaviour. Some factors put them at more risk of being bullied, but not all kids with these characteristics will be bullied. Sometimes, these individuals may need help learning how to respond to bullying.

Who is at risk?

No single factor puts a young person at risk of being bullied or bullying others. Bullying can happen anywhere—cities, suburbs, or rural towns. Depending on the environment, some groups—such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning (LGBTQ) youth, youth with disabilities, and socially isolated youth—may be at an increased risk of being bullied.

Those at Risk of Being Bullied

Generally, those who are bullied have one or more risk factors. Adolescents that are perceived as different from their peers, such as being overweight or underweight, wearing glasses or different clothing, being new to a school, or being unable to afford what kids consider “cool” are at risk for bullying. As are those perceived as weak or unable to defend themselves or are less popular than others and have few friends. Also, at risk for bullying are those that are depressed, anxious, or have low self-esteem. Finally, those that do not get along well with others, are seen as annoying or provoking, or antagonize others for attention are more likely to be bullied. However, even if a young person has these risk factors, it does not mean that they will be bullied.

Those More Likely to Bully Others

There are two types of kids who are more likely to bully others. The first is well-connected to their peers, have social power, are overly concerned about their popularity, and like to dominate or be in charge of others. The others are more isolated from their peers and may be depressed or anxious, have low self-esteem, be less involved in school, be easily pressured by peers, or not identify with the emotions or feelings of others.

There are specific risk factors that make someone more likely to bully others. Those that are aggressive or easily frustrated, have difficulty following rules, and view violence in a positive way are more likely to bully. Also, those that think badly of others and have friends who bully are at higher risk for the same behaviour. Finally, kids that have less parental involvement or are having issues at home may display more bullying behaviours.

Remember, those who bully others do not need to be stronger or bigger than those they bully. The power imbalance can come from several sources—popularity, strength, cognitive ability—and young person who bullies may have more than one of these characteristics.

Warning signs

There are many warning signs that may indicate that someone is affected by bullying—either being bullied or bullying others. Recognizing the warning signs is an essential first step in taking action against bullying. Not all young person who are bullied or are bullying others ask for help.

It is important to talk with young person who show signs of being bullied or bullying others. These warning signs can also point to other issues or problems, such as depression or substance abuse. Talking to the young person can help identify the root of the problem.

Signs of being bullied

Look for changes in the young person. However, be aware that not all young person who are bullied exhibit warning signs. Some signs that may point to a bullying problem are unexplainable injuries or lost and destroyed clothing, books, electronics, or jewelry. Those being bullied may report frequent headaches or stomach aches, feeling sick or faking illness. They may have changes in eating habits, like suddenly skipping meals or binge eating. Kids may come home from school hungry because they did not eat lunch. They may also have difficulty sleeping or frequent nightmares.

Signs of bullying others

Kids may be bullying others if they get into physical or verbal fights or have friends who bully others. They may demonstrate increasing levels of aggressive behaviour and get sent to the principal’s office or detention frequently. They may also have unexplained extra money or new belongings.

Why don’t kids ask for help?

Statistics from the 2012 Indicators of School Crime and Safety show that an adult was notified in less than half (40%) of bullying incidents. Kids do not tell adults for many reasons. Fo one, bullying can make a young person feel helpless. Kids may want to handle it on their own to feel in control again. They may fear being seen as weak or a tattletale. Kids may fear backlash from the kid who bullied them. Bullying can be a humiliating experience. Kids may not want adults to know what is being said about them, whether true or false. They may also fear that adults will judge them or punish them for being weak. Kids who are bullied may already feel socially isolated. They may feel like no one cares or could understand. Finally, kids may fear being rejected by their peers. Friends can help protect kids from bullying, and kids can fear of losing this support.

Effects of bullying

Bullying can affect everyone—those who are bullied, those who bully, and those who witness bullying. Bullying is linked to many negative outcomes, including impacts on mental health, substance use, and suicide. It is important to talk to kids to determine whether bullying—or something else—is a concern.

Kids who are bullied

Kids who are bullied can experience negative physical, school, and mental health issues. Kids who are bullied are more likely to experience depression and anxiety, increased feelings of sadness and loneliness, changes in sleep and eating patterns, and loss of interest in activities they used to enjoy. These issues may persist into adulthood. They may have more health complaints. Decreased academic achievement and school participation is a common effect of being bullied. They are also more likely to miss, skip, or drop out of school. A very small number of bullied kids might retaliate through extremely violent measures. In 12 of 15 school shooting cases in the 1990s, the shooters had a history of being bullied.

Kids who bully others

Kids who bully others can also engage in violent and other risky behaviours into adulthood. Kids who bully are more likely to abuse alcohol and other drugs in adolescence and as adults. They are also more likely to get into fights, vandalize property, and drop out of school. They can have criminal convictions and traffic citations as adults. They may engage in early sexual activity. They are also more likely to be abusive toward their romantic partners, spouses, or young person as adults.

For more information, visit PREVNet.ca

Aggression and Antisocial Behaviour

Several major theories of the development of antisocial behaviour treat adolescence as an important period. Patterson’s (1982) early versus late starter model of the development of aggressive and antisocial behaviour distinguishes youths whose antisocial behaviour begins during childhood (early starters) versus adolescence (late starters). According to the theory, early starters are at greater risk for long-term antisocial behaviour that extends into adulthood than are late starters. Late starters who become antisocial during adolescence are theorized to experience poor parental monitoring and supervision, aspects of parenting that become more salient during adolescence. Poor monitoring and lack of supervision contribute to increasing involvement with deviant peers, which in turn promotes adolescents’ own antisocial behaviour. Late starters desist from antisocial behaviour when changes in the environment make other options more appealing.

Similarly, Moffitt’s (1993) life-course persistent versus adolescent-limited model distinguishes between antisocial behaviour that begins in childhood versus adolescence. Moffitt regards adolescent-limited antisocial behaviour as resulting from a “maturity gap” between adolescents’ dependence on and control by adults and their desire to demonstrate their freedom from adult constraint. However, as they continue to develop, and legitimate adult roles and privileges become available to them, there are fewer incentives to engage in antisocial behaviour, leading to desistance in these antisocial behaviours.

Acting up, being disruptive, or even being defiant can occur during adolescence – teens are cycling through emotions at a rapid rate thanks to hormones, their interpretation of a situation, and other factors. These are typically short-term, and typically are not long-lasting (American Academy of Psychiatry, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). Children and young people who display aggressive behaviour can be at higher risk to develop issues with aggression, substance use, or other mental health concerns as adolescents (CAMH, 2023).

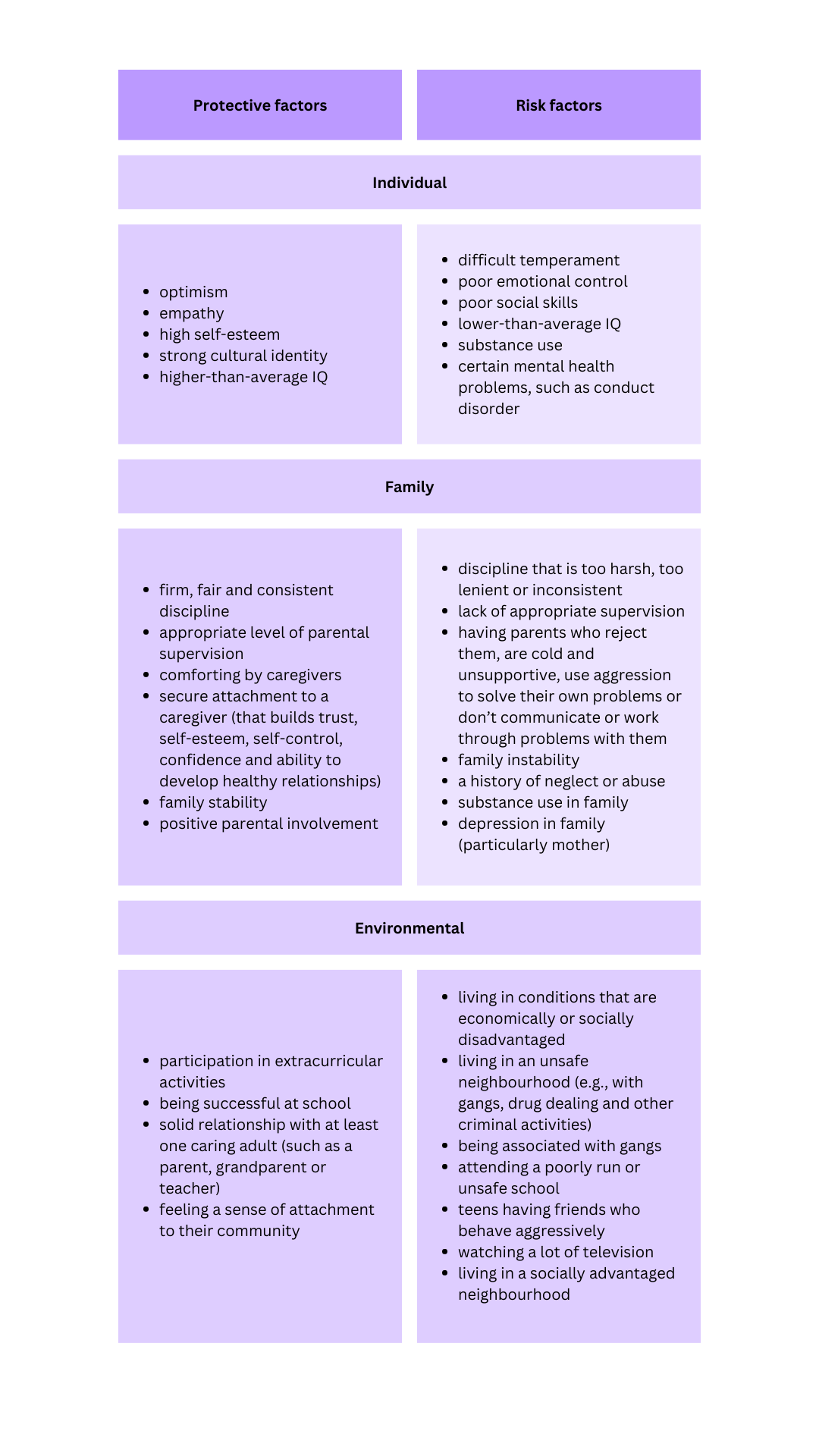

The reason for aggressive behaviour can be complex, however there are risk and protective factors that can affect potential behaviour. CAMH (2023) provides the following list of individual, family, and environmental risk and protective factors.

CAMH (2023) outlines the following as important to consider when determining if a young person’s aggressive behaviour is potential for concern:

- how regularly the behaviour occurs (daily, weekly, monthly), and if it has been getting worse over time

- how long this behaviour has been present

- if concerns go beyond behaviour and could be a result of something other than aggression

- how the behaviour impacts relationships with others – caregivers, siblings, peers, teachers, CYCPs, etc.

- the young person’s friend group and their general behaviours (e.g., if they also behave in ways that are aggressive or considered anti-social)

- how the young person is able to regulate their emotions (e.g., having an emotional outburst during a situation that typically doesn’t affect their peers, and how easy it is to calm the individual following the outburst

Disruptive Behaviour Disorders

According to the American Academy of Psychiatry (2018, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019),

Disruptive, impulse-control and conduct disorders refer to a group of disorders that include oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, kleptomania and pyromania. These disorders can cause people to behave angrily or aggressively toward people or property. They may have difficulty controlling their emotions and behaviour and may break rules or laws. An estimated 6 percent of children are affected by oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder.

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD): There is a recurrent pattern of negative, defiant, disobedient, and hostile behaviour toward authority figures. A young person diagnosed with ODD may argue and deliberately annoy others (Children’s Mental Health Services, 2020). It is important to remember that this is toward authority figures and not their peers. This occurs outside of normal developmental levels and leads to impairment in functioning (Lack, 2010). Young people with a diagnosis of ODD may also have other coexisting diagnoses such as ADHD, anxiety, or depression (CHADD.org, 2023; Children’s Mental Health Services, 2020).

Conduct Disorder (CD): Children diagnosed with Conduct Disorder (CD) show acts of aggression towards others and animals, are typically characterized as being easily irritable and often reckless, as well as having many temper tantrums despite their projected “tough” image portrayed to society, and show little to no compassion or concern for others or their feelings. Also, concern for the well-being of others is at a minimum. Young people with a diagnosis of CD also perceive the actions and intentions of others as more harmful and threatening than they actually are and respond with what they feel is reasonable and justified aggression. They may lack feelings of guilt or remorse. Since these individuals learn that expressing guilt or remorse may help in avoiding or lessening punishment, it may be difficult to evaluate when their guilt or remorse is genuine. Individuals will also try and place blame on others for the wrong doings that they had committed. These young people tend to have lower levels of self-esteem, and the diagnosis often accompanies early onset of sexual behaviour, drinking, smoking, use of illegal drugs, and reckless acts. Illegal drug use may increase the risk of the disorder persisting. The disorder may lead to school suspension or expulsion, problems at work, legal difficulties, STI’s, unplanned pregnancy, and injury from fights or accidents. Suicidal ideation and attempts occur at a higher rate than expected.

Aggression and youth dating violence

PREVNet is an organization based out of Queen’s University that researches violence and aggression, and publishes resources to support and promote healthy relationships for youth. Relationships are described as existing on a “continuum from healthy to unhealthy to abusive. Unhealthy relationship behaviours may not directly harm or infringe on a partner’s rights, while abusive behaviours tend to involve aggression, threats, manipulation, and coercion” (PREVNet, 2023b).

They offer training modules for adults who work with children and youth that describe healthy relationships. They also provide the following descriptions:

- Considerations about adolescent relationships:

- Romantic dating relationships generally increase during adolescence, becoming common by age 15.

- Dating relationships (and dating violence) can start as early as 6th grade.

- Adolescent dating relationships have unique characteristics compared to adult ones.

- For example, non-monogamous partnerships, casual relationships, and high use of social media for relationships are more common among adolescent relationships.

- Over the course of adolescence, there are many changes in attitudes, beliefs, norms, and overall identity that influence relationships.

- Romantic dating relationships generally increase during adolescence, becoming common by age 15.

- Dating violence is aggressive, violent, threatening, and/or manipulative behaviour from a partner.

- Types of dating violence:

- Physical: Use or threat of physical force

- Examples: Hitting, kicking, shoving, attacking with a weapon

- Sexual: Limiting individual’s sexual agency

- Examples: Unwanted sexual contact (kissing, touching), forced sex, sexual coercion, restricting access to birth control (removes agency from own sexual health)

- Emotional & Psychological: Manipulation, controlling partner’s behaviour & agency, and undermining/belittling

- Examples: Insulting, threatening, monitoring, isolating, restricting access to friends, and stalking

- Cyber: Using technology to engage in dating violence

- Examples: Monitoring (e.g. using social media), threatening or harassing online, sexting coercion

- Physical: Use or threat of physical force

- Some acts of violence may be confusing to classify, such as using technology to sexually abuse — the types are a guideline to understand the many ways in which dating violence can occur.

- When violence is used to control a partner, this is called coercive control and is especially harmful.

- Individuals may and often do perpetrate more than one type of dating violence within an abusive relationship.

To learn more or to complete the training modules, visit: https://www.prevnet.ca/resources/healthy-relationships-tool/healthy-relationships-training-module

The Role of Biology in Aggression

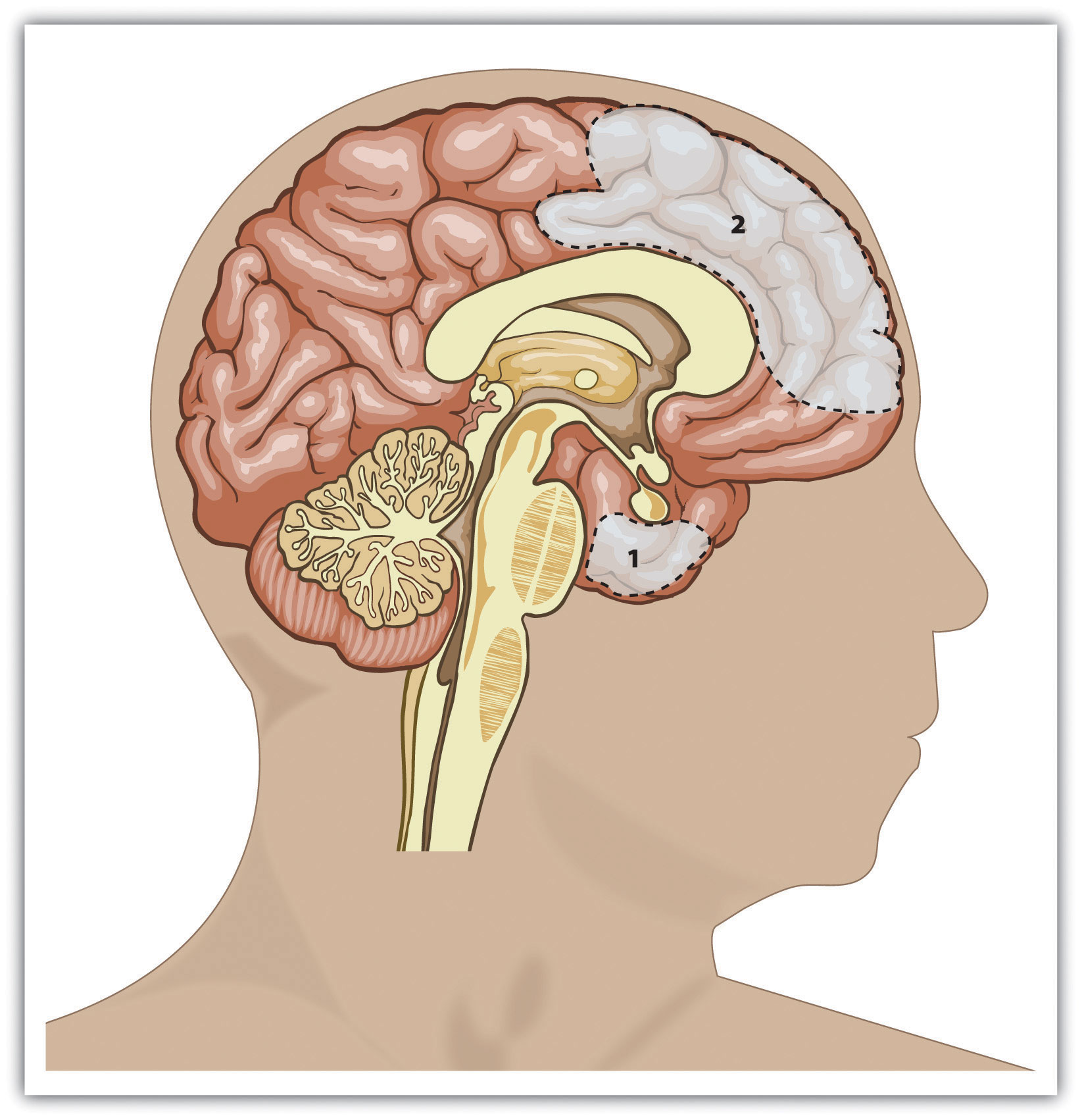

Aggression is controlled in large part by the area in the older part of the brain known as the amygdala (Figure 9.5, “Key Brain Structures Involved in Regulating and Inhibiting Aggression”). The amygdala is a brain region responsible for regulating our perceptions of, and reactions to, aggression and fear. The amygdala has connections with other body systems related to fear, including the sympathetic nervous system, facial responses, the processing of smells, and the release of neurotransmitters related to stress and aggression.

In addition to helping us experience fear, the amygdala also helps us learn from situations that create fear. The amygdala is activated in response to positive outcomes but also to negative ones, and particularly to stimuli that we see as threatening and fear arousing. When we experience events that are dangerous, the amygdala stimulates the brain to remember the details of the situation so that we learn to avoid it in the future. The amygdala is activated when we look at facial expressions of other people experiencing fear or when we are exposed to members of racial outgroups (Morris, Frith, Perrett, & Rowland, 1996; Phelps et al., 2000).

Although the amygdala helps us perceive and respond to danger, and this may lead us to aggress, other parts of the brain serve to control and inhibit our aggressive tendencies. One mechanism that helps us control our negative emotions and aggression is a neural connection between the amygdala and regions of the prefrontal cortex (Gibson, 2002).

The prefrontal cortex is in effect a control center for aggression: when it is more highly activated, we are more able to control our aggressive impulses. Research has found that the cerebral cortex is less active in murderers and death row inmates, suggesting that violent crime may be caused at least in part by a failure or reduced ability to regulate emotions (Davidson, Jackson, & Kalin, 2000; Davidson, Putnam, & Larson, 2000).

Brain regions that influence aggression include the amygdala (area 1) and the prefrontal cortex (area 2) as indicated in Image 5. Individual differences in one or more of these regions or in the interconnections among them can increase the propensity for impulsive aggression.

Hormones Influence Aggression: Testosterone and Serotonin

Hormones are also important in creating aggression. Most important in this regard is the male sex hormone testosterone, which is associated with increased aggression in both animals and in humans. Research conducted on a variety of animals has found a strong correlation between levels of testosterone and aggression. This relationship seems to be weaker among humans than among animals, yet it is still significant (Dabbs, Hargrove, & Heusel, 1996, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). Keep in mind that the observed relationships between testosterone levels and aggressive behaviour that have been found in these studies cannot prove that testosterone causes aggression—the relationships are only correlational.

In one study showing the relationship between testosterone and behaviour, James Dabbs and his colleagues (Dabbs, Hargrove, & Heusel, 1996, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019) measured the testosterone levels of 240 men who were members of 12 fraternities at two universities. They also obtained descriptions of the fraternities from university officials, fraternity officers, yearbook and chapter house photographs, and researcher field notes. The researchers correlated the testosterone levels and the descriptions of each of the fraternities. They found that the fraternities that had the highest average testosterone levels were also more wild and unruly, and in one case were known across campus for the crudeness of their behaviour. The fraternities with the lowest average testosterone levels, on the other hand, were more well-behaved, friendly, academically successful, and socially responsible. Another study found that juvenile delinquents and prisoners who have high levels of testosterone also acted more violently (Banks & Dabbs, 1996, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). Testosterone affects aggression by influencing the development of various areas of the brain that control aggressive behaviours. The hormone also affects physical development such as muscle strength, body mass, and height that influence our ability to successfully aggress.

Although testosterone levels are much higher in men than in women, the relationship between testosterone and aggression is not limited to males. Studies have also shown a positive relationship between testosterone and aggression and related behaviours (such as competitiveness) in women (Cashdan, 2003, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). Although women have lower levels of testosterone overall, they are more influenced by smaller changes in these levels than are men.

Testosterone is not the only biological factor linked to human aggression. Recent research has found that serotonin is also important, as serotonin tends to inhibit aggression. Low levels of serotonin have been found to predict future aggression (Kruesi, Hibbs, Zahn, & Keysor, 1992; Virkkunen, de Jong, Bartko, & Linnoila, 1989). Violent criminals have lower levels of serotonin than do nonviolent criminals, and criminals convicted of impulsive violent crimes have lower serotonin levels than criminals convicted of premeditated crimes (Virkkunen, Nuutila, Goodwin, & Linnoila, 1987).

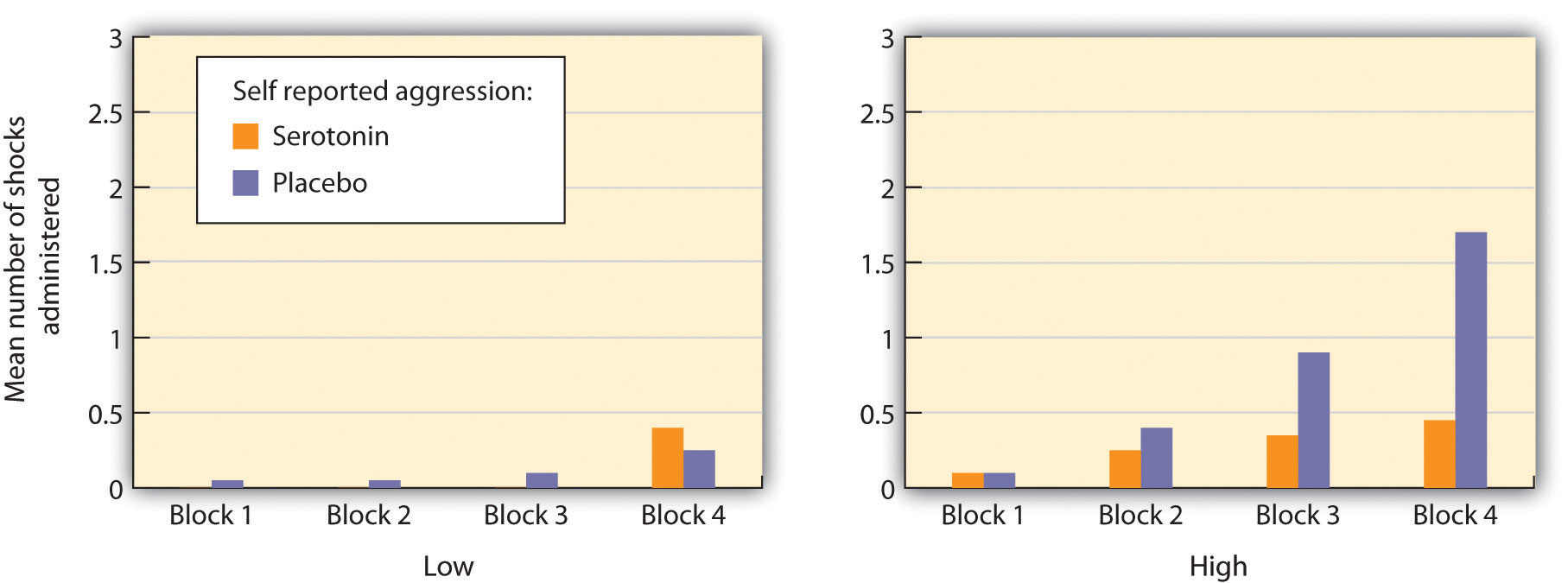

In one experiment assessing the influence of serotonin on aggression, Berman, McCloskey, Fanning, Schumacher, and Coccaro (2009) first chose two groups of participants, one of which indicated that they had frequently engaged in aggression (temper outbursts, physical fighting, verbal aggression, assaults, and aggression toward objects) in the past, and a second group that reported that they had not engaged in aggressive behaviours.

In a laboratory setting, participants from both groups were then randomly assigned to receive either a drug that raises serotonin levels or a placebo. Then the participants completed a competitive task with what they thought was another person in another room. (The opponent’s responses were actually controlled by computer.) During the task, the person who won each trial could punish the loser of the trial by administering electric shocks to the finger. Over the course of the game, the “opponent” kept administering more intense shocks to the participants.

As you can see in Image 6, the participants who had a history of aggression were significantly more likely to retaliate by administering severe shocks to their opponent than were the less aggressive participants. The aggressive participants who had been given serotonin, however, showed significantly reduced aggression levels during the game. Increased levels of serotonin appear to help people and animals inhibit impulsive responses to unpleasant events (Soubrié, 1986).

Participants who reported having engaged in a lot of aggressive behaviours (right panel) showed more aggressive responses in a competitive game than did those who reported being less aggressive (left panel). The aggression levels for the more aggressive participants increased over the course of the experiment for those who did not take a dosage of serotonin but aggression did not significantly increase for those who had taken serotonin. Data are from Berman et al. (2009).

Alcohol consumption and aggression

Perhaps unsurprisingly, research has found that the consumption of alcohol increases aggression. In fact, excessive alcohol consumption is involved in a majority of violent crimes, including rape and murder (Abbey, Ross, McDuffie, & McAuslan, 1996). The evidence is very clear, both from correlational research designs and from experiments in which participants are randomly assigned either to ingest or not ingest alcohol, that alcohol increases the likelihood that people will respond aggressively to provocations (Bushman, 1997; Graham, Osgood, Wells, & Stockwell, 2006; Ito, Miller, & Pollock, 1996). Even people who are not normally aggressive may react with aggression when they are intoxicated (Bushman & Cooper, 1990).

Alcohol increases aggression for a couple of reasons. First, alcohol disrupts executive functions, which are the cognitive abilities that help us plan, organize, reason, achieve goals, control emotions, and inhibit behavioual tendencies (Séguin & Zelazo, 2005). Executive functioning occurs in the prefrontal cortex, which is the area that allows us to control aggression. Alcohol therefore reduces the ability of the person who has consumed it to inhibit his or her aggression (Steele & Southwick, 1985). Acute alcohol consumption is more likely to facilitate aggression in people with low, rather than high, executive functioning abilities.

Second, when people are intoxicated, they become more self-focused and less aware of the social situation, a state that is known as alcohol myopia. As a result, they are less likely to notice the social constraints that normally prevent them from engaging aggressively and are less likely to use those social constraints to guide them. We might normally notice the presence of a police officer or other people around us, which would remind us that being aggressive is not appropriate, but when we are drunk we are less likely to be so aware. The narrowing of attention that occurs when we are intoxicated also prevents us from being aware of the negative outcomes of our aggression. When we are sober, we realize that being aggressive may produce retaliation as well as cause a host of other problems, but we are less likely to be aware of these potential consequences when we have been drinking (Bushman & Cooper, 1990).

Alcohol also influences aggression through expectations. If we expect that alcohol will make us more aggressive, then we tend to become more aggressive when we drink. The sight of a bottle of alcohol or an alcohol advertisement increases aggressive thoughts and hostile attributions about others (Bartholow & Heinz, 2006), and the belief that we have consumed alcohol increases aggression (Bègue et al., 2009).

Negative emotions and aggression

If you were to try to recall the times that you have been aggressive, you would probably report that many of them occurred when you were angry, in a bad mood, tired, in pain, sick, or frustrated. And you would be right—we are much more likely to aggress when we are experiencing negative emotions. When we are feeling ill, when we get a poor grade on an exam, or when our car doesn’t start—in short, when we are angry and frustrated in general—we are likely to have many unpleasant thoughts and feelings, and these are likely to lead to violent behaviour. Aggression is caused in large part by the negative emotions that we experience as a result of the aversive events that occur to us and by our negative thoughts that accompany them (Berkowitz & Heimer, 1989).

One kind of negative affect that increases arousal when we are experiencing it is frustration (Berkowitz, 1989; Dollard, Doob, Miller, Mowrer, & Sears, 1939). Frustration occurs when we feel that we are not obtaining the important goals that we have set for ourselves. We get frustrated when our computer crashes while we are writing an important paper, when we feel that our social relationships are not going well, or when our schoolwork is going poorly. How frustrated we feel is also determined in large part through social comparison. If we can make downward comparisons with important others, in which we see ourselves as doing as well or better than they are, then we are less likely to feel frustrated. But when we are forced to make upward comparisons with others, we may feel frustration. When we receive a poorer grade than our classmates received or when we are paid less than our coworkers, this can be frustrating to us.

Although frustration is an important cause of the negative affect that can lead to aggression, there are other sources as well. In fact, anything that leads to discomfort or negative emotions can increase aggression. Consider pain, for instance. Berkowitz (1993b) reported a study in which participants were made to feel pain by placing their hands in a bucket of ice-cold water, and it was found that this source of pain also increased subsequent aggression. As another example, working in extremely high temperatures is also known to increase aggression—when we are hot, we are more aggressive. Griffit and Veitch (1971) had students complete questionnaires either in rooms in which the heat was at a normal temperature or in rooms in which the temperature was over 32 degrees Celsius (90 degrees Fahrenheit). The students in the latter condition expressed significantly more hostility.

Hotter temperatures are associated with higher levels of aggression (Image 7) and violence (Anderson, Anderson, Dorr, DeNeve, & Flanagan, 2000). Hotter regions generally have higher violent crime rates than cooler regions, and violent crime is greater on hot days than it is on cooler days, and during hotter years than during cooler years (Bushman, Wang, & Anderson, 2005). Even the number of baseball batters hit by pitches is higher when the temperature at the game is higher (Reifman, Larrick, & Fein, 1991). Researchers who study the relationship between heat and aggression have proposed that global warming is likely to produce even more violence (Anderson & Delisi, 2011).

Conclusion

Social relationships for adolescents can deeply influence behaviours, temperament, identity, and can factor in to shape future relationship expectations. Emotional development can also factor into these relationships, and are a result of learning, environment, interactions with others, and circumstances. This can include healthy relationships with caregivers, family, the community, and the support received during earlier developmental stages. If there were areas of development that weren’t met, that doesn’t mean the young person can’t benefit from support later in life. It means that as CYCPs, we can recognize needs, and work towards addressing and supporting them.

Next week’s reading will focus on the opportunities we have as CYCPs to address these general challenges and support healthy development.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

CAMH.ca (2023). Aggressive behaviour in children and youth: When is it something to be concerned about? https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/guides-and-publications/aggressive-behaviour-in-children-and-youth

CHADD.org. (2023). ADHD and Disruptive Behavior Disorders. https://chadd.org/about-adhd/disruptive-behavior-disorders/

Children’s Mental Health Services. (2020). Disruptive behaviour disorders. https://www.cmhsonline.ca/parents-behaviour-disorders

Fallon, B., Lefebvre, R., Trocmé, N., Richard, K., Hélie, S., Montgomery, H. M., Bennett, M., Joh-Carnella, N., Saint-Girons, M., Filippelli, J., MacLaurin, B., Black, T., Esposito, T., King, B., Collin- Vézina, D., Dallaire, R., Gray, R., Levi, J., Orr, M., Petti, T., Thomas Prokop, S., & Soop, S. (2021). Denouncing the continued overrepresentation of First Nations children in Canadian child welfare: Findings from the First Nations/Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect-2019. Ontario: Assembly of First Nations.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life course persistent antisocial behaviour: Developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Patterson, G. R. (1982). Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia Press.

PREVNet.ca. (2023a). Cyberbullying. https://www.prevnet.ca/bullying/cyber-bullying

PREVNet.ca. (2023b). Teen dating violence. https://www.prevnet.ca/teen-dating-violence

Rudolph, K. D. (2009). The interpersonal context of adolescent depression. In S. Nolen-Hoeksema & L. M. Hilt (Eds.), Handbook of depression in adolescents (pp. 377–418). New York, NY: Taylor and Francis.

OER Attributions:

Content from this chapter has been adapted from the following sources:

Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.