Physical Development in Adolescence

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will:

- Describe the physical changes that occur in adolescence and their impact on development.

- List the areas of the brain important during adolescence.

Physical changes of puberty mark the onset of adolescence (Lerner & Steinberg, 2009). This reading will describe the main physical changes of the brain and body typically experienced by adolescents. This may be a somewhat outdated view, however, as children can experience puberty as early as middle childhood – between eight and thirteen years of age.

Most literature and research surrounding human growth and development, for the most part, describes development in terms of sex assigned at birth. This includes “the assignment and classification of people as male, female, intersex, or another sex assigned at birth often based on physical anatomy at birth” (Trans Student Educational Resources, n.d.) which includes both biological and physical features “such as chromosomes, genitals and hormones” (Statistics Canada, 2021).

For the purpose of clarity, any reference to boys, girls, male/female anatomy, physiology, or physical development in our readings refers to changes that occur based on the sex assigned at birth, unless otherwise noted.

For both boys and girls (sex assigned at birth), these changes include a growth spurt in height, growth of pubic and underarm hair, and skin changes (e.g., pimples). Boys also experience growth in facial hair and a deepening of their voice. Girls experience breast development and begin menstruating. These pubertal changes are driven by hormones, particularly an increase in testosterone for boys and estrogen for girls.

The physical changes that occur during adolescence are greater than those of any other time of life, with the exception of infancy. In some ways, however, the changes in adolescence are more dramatic than those that occur in infancy—unlike infants, adolescents are aware of the changes that are taking place and of what the changes mean. In this section, you will learn about the pubertal changes in body size, proportions, and sexual maturity, the social and emotional attitudes and reactions toward puberty, and some of the health concerns during adolescence, including eating disorders.

Physical Development during Adolescence

Puberty Begins

Puberty is the period of rapid growth and sexual development that begins in adolescence and starts at some point between ages 8 and 14. While the sequence of physical changes in puberty is predictable, the onset and pace of puberty vary widely. Every person’s individual timetable for puberty is different and is primarily influenced by heredity; however environmental factors—such as diet and exercise—also exert some influence.

Adolescence has evolved historically, with evidence indicating that this stage is lengthening as individuals start puberty earlier and transition to adulthood later than in the past. Puberty today begins, on average, at age 10–11 years for girls and 11–12 years for boys. This average age of onset has decreased gradually over time since the 19th century by 3–4 months per decade, which has been attributed to a range of factors including better nutrition, obesity, increased father absence, and other environmental factors (Steinberg, 2013). Completion of formal education, financial independence from parents, marriage, and parenthood have all been markers of the end of adolescence and beginning of adulthood, and all of these transitions happen, on average, later now than in the past. In fact, the prolonging of adolescence has prompted the introduction of a new developmental period called emerging adulthood that captures these developmental changes out of adolescence and into adulthood, occurring from approximately ages 18 to 29 (Arnett, 2000). We’ll learn more about this phase later in the semester.

Hormonal Changes

Puberty involves distinctive physiological changes in an individual’s height, weight, body composition, and circulatory and respiratory systems, and during this time, both the adrenal glands and sex glands mature. These changes are largely influenced by hormonal activity. Many hormones contribute to the beginning of puberty, but most notably a major rush of estrogen for girls and testosterone for boys. Hormones play an organizational role (priming the body to behave in a certain way once puberty begins) and an activational role (triggering certain behavioral and physical changes). During puberty, the adolescent’s hormonal balance shifts strongly towards an adult state; the process is triggered by the pituitary gland, which secretes a surge of hormonal agents into the blood stream and initiates a chain reaction.

Puberty occurs over two distinct phases, and the first phase, adrenarche, begins at 6 to 8 years of age and involves increased production of adrenal androgens that contribute to a number of pubertal changes—such as skeletal growth. The second phase of puberty, gonadarche, begins several years later and involves increased production of hormones governing physical and sexual maturation.

Sexual Maturation

During puberty, primary and secondary sex characteristics develop and mature. Primary sex characteristics are organs specifically needed for reproduction—the uterus and ovaries in females and testes in males. Secondary sex characteristics are physical signs of sexual maturation that do not directly involve sex organs, such as development of breasts and hips in girls, and development of facial hair and a deepened voice in boys. Both sexes experience development of pubic and underarm hair, as well as increased development of sweat glands.

The male and female gonads are activated by the surge of the hormones discussed earlier, which puts them into a state of rapid growth and development. The testes primarily release testosterone and the ovaries release estrogen; the production of these hormones increases gradually until sexual maturation is met.

For girls, observable changes begin with nipple growth and pubic hair. Then the body increases in height while fat forms particularly on the breasts and hips. The first menstrual period (menarche) is followed by more growth, which is usually completed by four years after the first menstrual period began. Girls experience menarche usually around 12–13 years old. For boys, the usual sequence is growth of the testes, initial pubic-hair growth, growth of the penis, first ejaculation of seminal fluid (spermarche), appearance of facial hair, a peak growth spurt, deepening of the voice, and final pubic-hair growth. (Herman-Giddens et al, 2012). Boys experience spermarche, the first ejaculation, around 13–14 years old.

Physical Growth: The Growth Spurt

During puberty, both sexes experience a rapid increase in height and weight (referred to as a growth spurt) over about 2-3 years resulting from the simultaneous release of growth hormones, thyroid hormones, and androgens. Males experience their growth spurt about two years later than females. For girls the growth spurt begins between 8 and 13 years old (average 10-11), with adult height reached between 10 and 16 years old. Boys begin their growth spurt slightly later, usually between 10 and 16 years old (average 12-13), and reach their adult height between 13 and 17 years old. Both nature (i.e., genes) and nurture (e.g., nutrition, medications, and medical conditions) can influence both height and weight.

Before puberty, there are nearly no differences between males and females in the distribution of fat and muscle. During puberty, males grow muscle much faster than females, and females experience a higher increase in body fat and bones become harder and more brittle. An adolescent’s heart and lungs increase in both size and capacity during puberty; these changes contribute to increased strength and tolerance for exercise.

Watch It

Watch this video to see a summary of the main biological changes that occur during puberty.

Reactions Toward Puberty and Physical Development

The accelerated growth in different body parts happens at different times, but for all adolescents it has a fairly regular sequence. The first places to grow are the extremities (head, hands, and feet), followed by the arms and legs, and later the torso and shoulders. This non-uniform growth is one reason why an adolescent body may seem out of proportion. Additionally, because rates of physical development vary widely among teenagers, puberty can be a source of pride or embarrassment.

Most adolescents want nothing more than to fit in and not be distinguished from their peers in any way, shape or form (Mendle, 2015). So when a child develops earlier or later than his or her peers, there can be long-lasting effects on mental health. Simply put, beginning puberty earlier than peers presents great challenges, particularly for girls. The picture for early-developing boys isn’t as clear, but evidence suggests that they, too, eventually might suffer ill effects from maturing ahead of their peers. The biggest challenges for boys, however, seem to be more related to late development.

As mentioned in the Khan Academy video about physical development, early maturing boys tend to be stronger, taller, and more athletic than their later maturing peers. They are usually more popular, confident, and independent, but they are also at a greater risk for substance abuse and early sexual activity (Flannery, Rowe, & Gulley, 1993; Kaltiala-Heino, Rimpela, Rissanen, & Rantanen, 2001). Additionally, more recent research found that while early-maturing boys initially had lower levels of depression than later-maturing boys, over time they showed signs of increased anxiety, negative self-image and interpersonal stress. (Rudolph, Troop-Gordon, Lambert, & Natsuaki, 2014).

Early maturing girls may be teased or overtly admired, which can cause them to feel self-conscious about their developing bodies. These girls are at increased risk of a range of psychosocial problems including depression, substance use and early sexual behavior (Graber, 2013). These girls are also at a higher risk for eating disorders, which we will discuss in more detail later in the course (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 2001; Graber, Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Brooks-Gunn, 1997; Striegel-Moore & Cachelin, 1999).

Late blooming boys and girls (i.e., they develop more slowly than their peers) may feel self-conscious about their lack of physical development. Negative feelings are particularly a problem for late maturing boys, who are at a higher risk for depression and conflict with parents (Graber et al., 1997) and more likely to be bullied (Pollack & Shuster, 2000).

Brain Development During Adolescence

The human brain is not fully developed by the time a person reaches puberty. Between the ages of 10 and 25, the brain undergoes changes that have important implications for behavior. The brain reaches 90% of its adult size by the time a person is six or seven years of age. Thus, the brain does not grow in size much during adolescence. However, the creases in the brain continue to become more complex until the late teens. The biggest changes in the folds of the brain during this time occur in the parts of the cortex that process cognitive and emotional information.

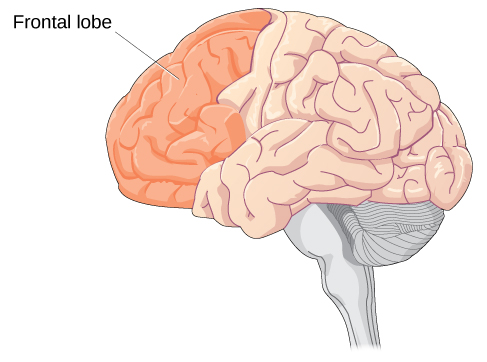

Up until puberty, brain cells continue to bloom in the frontal region. Some of the most developmentally significant changes in the brain occur in the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in decision making and cognitive control, as well as other higher cognitive functions. During adolescence, myelination and synaptic pruning in the prefrontal cortex increase, improving the efficiency of information processing, and neural connections between the prefrontal cortex and other regions of the brain are strengthened. However, this growth takes time and the growth is uneven.

The Teen Brain: 6 Things to Know

As you learn about brain development during adolescence, consider these six facts from the The National Institute of Mental Health:

Your brain does not keep getting bigger as you get older

For girls, the brain reaches its largest physical size around 11 years old and for boys, the brain reaches its largest physical size around age 14. Of course, this difference in age does not mean either boys or girls are smarter than one another!

But that doesn’t mean your brain is done maturing

For both boys and girls, although your brain may be as large as it will ever be, your brain doesn’t finish developing and maturing until your mid- to late-20s. The front part of the brain, called the prefrontal cortex, is one of the last brain regions to mature. It is the area responsible for planning, prioritizing and controlling impulses.

The teen brain is ready to learn and adapt

In a digital world that is constantly changing, the adolescent brain is well prepared to adapt to new technology—and is shaped in return by experience.

Many mental disorders appear during adolescence

All the big changes the brain is experiencing may explain why adolescence is the time when many mental disorders—such as schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and eating disorders—emerge.

The teen brain is resilient

Although adolescence is a vulnerable time for the brain and for teenagers in general, most teens go on to become healthy adults. Some changes in the brain during this important phase of development actually may help protect against long-term mental disorders.

Teens need more sleep than children and adults

Although it may seem like teens are lazy, science shows that melatonin levels (or the “sleep hormone” levels) in the blood naturally rise later at night and fall later in the morning than in most children and adults. This may explain why many teens stay up late and struggle with getting up in the morning. Teens should get about 9-10 hours of sleep a night, but most teens don’t get enough sleep. A lack of sleep makes paying attention hard, increases impulsivity and may also increase irritability and depression.

The limbic system develops years ahead of the prefrontal cortex. Development in the limbic system plays an important role in determining rewards and punishments and processing emotional experience and social information. Pubertal hormones target the amygdala directly and powerful sensations become compelling (Romeo, 2013). Brain scans confirm that cognitive control, revealed by fMRI studies, is not fully developed until adulthood because the prefrontal cortex is limited in connections and engagement (Hartley & Somerville, 2015). Recall that this area is responsible for judgment, impulse control, and planning, and it is still maturing into early adulthood (Casey, Tottenham, Liston, & Durston, 2005).

Additionally, changes in both the levels of the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin in the limbic system make adolescents more emotional and more responsive to rewards and stress. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter in the brain associated with pleasure and attuning to the environment during decision-making. During adolescence, dopamine levels in the limbic system increase and input of dopamine to the prefrontal cortex increases. The increased dopamine activity in adolescence may have implications for adolescent risk-taking and vulnerability to boredom. Serotonin is involved in the regulation of mood and behavior. It affects the brain in a different way. Known as the “calming chemical,” serotonin eases tension and stress. Serotonin also puts a brake on the excitement and sometimes recklessness that dopamine can produce. If there is a defect in the serotonin processing in the brain, impulsive or violent behavior can result.

When the overall brain chemical system is working well, it seems that these chemicals interact to balance out extreme behaviors. But when stress, arousal or sensations become extreme, the adolescent brain is flooded with impulses that overwhelm the prefrontal cortex, and as a result, adolescents engage in increased risk-taking behaviors and emotional outbursts possibly because the frontal lobes of their brains are still developing.

Later in adolescence, the brain’s cognitive control centers in the prefrontal cortex develop, increasing adolescents’ self-regulation and future orientation. The difference in timing of the development of these different regions of the brain contributes to more risk taking during middle adolescence because adolescents are motivated to seek thrills that sometimes come from risky behavior, such as reckless driving, smoking, or drinking, and have not yet developed the cognitive control to resist impulses or focus equally on the potential risks (Steinberg, 2008). One of the world’s leading experts on adolescent development, Laurence Steinberg, likens this to engaging a powerful engine before the braking system is in place. The result is that adolescents are more prone to risky behaviors than are children or adults.

Watch It

This video further explains and highlights some of the key developments in the brain during adolescence.

As mentioned in the introduction to adolescence, too many who have read the research on the teenage brain come to quick conclusions about adolescents as irrational loose cannons. However, adolescents are actually making choices influenced by a very different set of chemical influences than their adult counterparts—a hopped up reward system that can drown out warning signals about risk. Adolescent decisions are not always defined by impulsivity because of lack of brakes, but because of planned and enjoyable pressure to the accelerator. It is helpful to put all of these brain processes in developmental context. Young people need to somewhat enjoy the thrill of risk taking in order to complete the incredibly overwhelming task of growing up.

Watch It

Watch the selected portion of this video to learn more about research related to brain changes and behavior during adolescence.

To learn more, watch this TED talk by Sarah-Jayne Blakemore: The mysterious workings of the adolescent brain (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6zVS8HIPUng) about the latest adolescent brain research and more about how these changes in brain development also result in behavioral changes.

Key Takeaways

In sum, the adolescent years are a time of intense brain changes. Interestingly, two of the primary brain functions develop at different rates. Brain research indicates that the part of the brain that perceives rewards from risk, the limbic system, kicks into high gear in early adolescence. The part of the brain that controls impulses and engages in longer-term perspective, the frontal lobes, mature later. This may explain why teens in mid-adolescence take more risks than older teens. As the frontal lobes become more developed, two things happen. First, self-control develops as teens are better able to assess cause and effect. Second, more areas of the brain become involved in processing emotions, and teens become better at accurately interpreting others’ emotions (Steinberg, 2008).

Sleep

Brain development even affects the way teens sleep. Adolescents’ normal sleep patterns are different from those of children and adults. Teens are often drowsy upon waking, tired during the day, and wakeful at night. Although it may seem like teens are lazy, science shows that melatonin levels (or the “sleep hormone” levels) in the blood naturally rise later at night and fall later in the morning in teens than in most children and adults. This may explain why many teens stay up late and struggle with getting up in the morning.

According to Canada’s 24-Hour movement guidelines, young people ages 5-13 years should have between 9 to 11 hours of uninterrupted sleep each night. For teens ages 14-17 years, the recommendations are 8 to 10 hours per night with consistent bed and wake-up times (Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth, 2022).

Link to Learning: School Start Times

As research reveals the importance of sleep for teenagers, many people advocate for later high school start times. Read about some of the research at the National Sleep Foundation on school start times (https://www.sleepfoundation.org/articles/backgrounder-later-school-start-times) or watch this TED talk by Wendy Troxel: “Why Schools Should Start Later for Teens” (https://www.ted.com/talks/wendy_troxel_why_school_should_start_later_for_teens/transcript?language=en).

Some Toronto high schools in the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) have implemented late start dates to address these needs. However, in the past, these have been impacted by other factors (Rushowy, 2016).

References

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth. (2022). Children and youth: Ages 5-17. Retrieved from: https://www.participaction.com/the-science/benefits-and-guidelines/children-and-youth-age-5-to-17/

Graber, J. A. (2013). Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior, 64, 262–269.

Hartley, C.A. & Somerville, L.H. (2015). The neuroscience of adolescent decision-making. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 5, 108-115.

Herman-Giddens, M.E., Steffes, J., Harris, D., Slora, E., Hussey, M., Dowshen, S.A, & Reiter, E.O. (2012). Secondary sexual characteristics in boys: Data from the pediatric research in office settings network. Pediatrics, 130(5), 1058-1068.

Lerner, R. M., & Steinberg, L. (2009). The scientific study of adolescent development: Historical and contemporary perspectives. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Individual bases of adolescent development (pp. 3–14). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy001002

Mendle, J., Moore, S. R., Briley, D. A., & Harden, K. P. (2015). Puberty, socioeconomic status, and depression in girls: Evidence for gene x environment interactions. Clinical Psychological Science. Advance online publication.

National Institute of Mental Health. The Teen Brain: 6 Things to Know. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/the-teen-brain-6-things-to-know/index.shtml#pub6

Romeo, R.D. (2013). The teenage brain: The stress response and the adolescent brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22 (2), 140-145.

Rudolph, K. D., Troop-Gordon, W., Lambert, S. F., & Natsuaki, M. N. (2014). Long-term consequences of pubertal timing for youth depression: Identifying personal and contextual pathways of risk. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 1423–1444.

Rushowy, K. (2016). Let us sleep! Teens call for return of late starts nixed by teachers’ job action. Retrieved from: https://www.thestar.com/yourtoronto/education/2016/02/08/let-us-sleep-teens-call-for-return-of-late-starts-nixed-by-teachers-job-action.html

Statistics Canada (2021). Sex at birth of person. https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Var.pl?Function=DEC&Id=24101

Steinberg, L. (2008) A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review, 28:78-106.

Steinberg, L. (2013). Adolescence (10th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Trans Student Educational Resources (n.d.) Definitions. Retrieved from: https://transstudent.org/about/definitions/