Identity and Self-Esteem

Introduction

Adolescence is a period of personal and social identity formation, in which different roles, behaviours, and ideologies are explored. Adolescence is seen as a time to develop independence from parents while remaining connected to them. Some key points related to social development during adolescence include the following:

- Adolescence is the period of life known for the formation of personal and social identity.

- Adolescents must explore, test limits, become autonomous, and commit to an identity, or sense of self.

- Erik Erikson referred to the task of the adolescent as one of identity versus role confusion. Thus, in Erikson’s view, an adolescent’s main questions are “Who am I?” and “Who do I want to be?”

- Early in adolescence, cognitive developments result in greater self-awareness, the ability to think about abstract, future possibilities, and the ability to consider multiple possibilities and identities at once.

- Changes in the levels of certain neurotransmitters (such as dopamine and serotonin) influence the way in which adolescents experience emotions, typically making them more emotional and more sensitive to stress.

- When adolescents have advanced cognitive development and maturity, they tend to resolve identity issues more easily than peers who are less cognitively developed.

- As adolescents work to form their identities, they pull away from their parents, and the peer group becomes very important; despite this, relationships with parents still play a significant role in identity formation.

Learning Outcomes

- Determine the essential elements of identity development and self-esteem in youth.

- Identify opportunities to promote healthy patterns of behaviour and mental wellness.

Identity Formation

Identity development is a stage in the adolescent life cycle. For most, the search for identity begins in the adolescent years. During these years, adolescents are more open to ‘trying on’ different behaviours and appearances to discover who they are. In an attempt to find their identity and discover who they are, adolescents are likely to cycle through a number of identities to find one that suits them best. Developing and maintaining identity (in adolescent years) is a difficult task due to multiple factors such as family life, environment, and social status. Empirical studies suggest that this process might be more accurately described as identity development, rather than formation, but confirms a normative process of change in both content and structure of one’s thoughts about the self.

Self-Concept

Two main aspects of identity development are self-concept and self-esteem. The idea of self-concept is known as the ability of a person to have opinions and beliefs that are defined confidently, consistently and with stability. Early in adolescence, cognitive developments result in greater self-awareness, greater awareness of others and their thoughts and judgments, the ability to think about abstract, future possibilities, and the ability to consider multiple possibilities at once. As a result, adolescents experience a significant shift from the simple, concrete, and global self-descriptions typical of young children; as children they defined themselves by physical traits whereas adolescents define themselves based on their values, thoughts, and opinions.

Adolescents can conceptualize multiple “possible selves” that they could become and long-term possibilities and consequences of their choices. Exploring these possibilities may result in abrupt changes in self-presentation as the adolescent chooses or rejects qualities and behaviours, trying to guide the actual self toward the ideal self (who the adolescent wishes to be) and away from the feared self (who the adolescent does not want to be). For many, these distinctions are uncomfortable, but they also appear to motivate achievement through behaviour consistent with the ideal and distinct from the feared possible selves.

Further distinctions in self-concept, called “differentiation,” occur as the adolescent recognizes the contextual influences on their own behaviour and the perceptions of others, and begin to qualify their traits when asked to describe themselves. Differentiation appears fully developed by mid-adolescence. Peaking in the 7th-9th grades, the personality traits adolescents use to describe themselves refer to specific contexts, and therefore may contradict one another. The recognition of inconsistent content in the self-concept is a common source of distress in these years, but this distress may benefit adolescents by encouraging structural development.

Self-Esteem

Another aspect of identity formation is self-esteem. Self-esteem is defined as one’s thoughts and feelings about one’s self-concept and identity. Most theories on self-esteem state that there is a grand desire, across all genders and ages, to maintain, protect and enhance their self-esteem. Contrary to popular belief, there is no empirical evidence for a significant drop in self-esteem over the course of adolescence. “Barometric self-esteem” fluctuates rapidly and can cause severe distress and anxiety, but baseline self-esteem remains highly stable across adolescence. The validity of global self-esteem scales has been questioned, and many suggest that more specific scales might reveal more about the adolescent experience. Girls are most likely to enjoy high self-esteem when engaged in supportive relationships with friends, the most important function of friendship to them is having someone who can provide social and moral support. When they fail to win friends’ approval or can’t find someone with whom to share common activities and common interests, in these cases, girls suffer from low self-esteem.

In contrast, boys are more concerned with establishing and asserting their independence and defining their relation to authority. As such, they are more likely to derive high self-esteem from their ability to successfully influence their friends; on the other hand, the lack of romantic competence, for example, failure to win or maintain the affection of the opposite or same-sex (depending on sexual orientation), is the major contributor to low self-esteem in adolescent boys.

Identity Formation: Who am I?

Adolescents continue to refine their sense of self as they relate to others. Erik Erikson referred to life’s fifth psychosocial task as one of identity versus role confusion when adolescents must work through the complexities of finding one’s own identity. Individuals are influenced by how they resolved all of the previous childhood psychosocial crises and this adolescent stage is a bridge between the past and the future, between childhood and adulthood. Thus, in Erikson’s view, an adolescent’s main questions are “Who am I?” and “Who do I want to be?” Identity formation was highlighted as the primary indicator of successful development during adolescence (in contrast to role confusion, which would be an indicator of not successfully meeting the task of adolescence). This crisis is resolved positively with identity achievement and the gain of fidelity (ability to be faithful) as a new virtue, when adolescents have reconsidered the goals and values of their parents and culture. Some adolescents adopt the values and roles that their parents expect for them. Other teens develop identities that are in opposition to their parents but align with a peer group. This is common as peer relationships become a central focus in adolescents’ lives.

Expanding on Erikson’s theory, Marcia (1966) described identify formation during adolescence as involving both decision points and commitments with respect to ideologies (e.g., religion, politics) and occupations. Foreclosure occurs when an individual commits to an identity without exploring options. Identity confusion/diffusion occurs when adolescents neither explore nor commit to any identities. Moratorium is a state in which adolescents are actively exploring options but have not yet made commitments. As mentioned earlier, individuals who have explored different options, discovered their purpose, and have made identity commitments are in a state of identity achievement.

Developmental psychologists have researched several different areas of identity development and some of the main areas include:

- Religious identity: The religious views of teens are often similar to those of their families (Kim-Spoon, Longo, & McCullough, 2012) Most teens may question specific customs, practices, or ideas in the faith of their parents, but few completely reject the religion of their families.

- Political identity: An adolescent’s political identity is also influenced by their parents’ political beliefs. A new trend in the 21st century is a decrease in party affiliation among adults. Many adults do not align themselves with either the democratic or republican party and their teenage children reflect their parents’ lack of party affiliation. Although adolescents do tend to be more liberal than their elders, especially on social issues (Taylor, 2014, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019), like other aspects of identity formation, adolescents’ interest in politics is predicted by their parents’ involvement and by current events (Stattin et al., 2017, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019).

- Vocational identity: While adolescents in earlier generations envisioned themselves as working in a particular job, and often worked as an apprentice or part-time in such occupations as teenagers, this is rarely the case today. Vocational identity takes longer to develop, as most of today’s occupations require specific skills and knowledge that will require additional education or are acquired on the job itself. In addition, many of the jobs held by teens are not in occupations that most teens will seek as adults.

- Ethnic identity: Ethnic identity refers to how people come to terms with who they are based on their ethnic or racial ancestry. According to the 2021 Canadian census (Statistics Canada, 2022) more than 35.5% of Canadians identified being part of one or more ethnocultural, racialized, and religious groups. For many teens, discovering one’s ethnic identity is an important part of identity formation. Phinney (1989, as as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019) proposed a model of ethnic identity development that included stages of unexplored ethnic identity, ethnic identity search, and achieved ethnic identity.

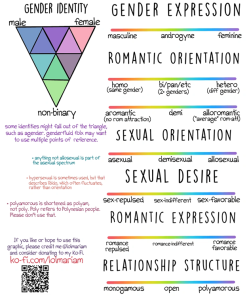

Figure 1: The Orientation & Identities Diagram “allows a person to map out their gender identity, gender expression and orientation” (LGBTQIA+ Wiki, n.d.) - Gender identity: A person’s sex, as determined by their biology, does not always correspond with their gender. Sex refers to the biological differences between males and females, such as the genitalia and genetic differences. Gender refers to the socially constructed characteristics of women and men, such as norms, roles, and relationships between groups of women and men. Many adolescents use their analytic, hypothetical thinking to question traditional gender roles and expression. If their genetically assigned sex does not line up with their gender identity, they may refer to themselves as transgender, non-binary, or gender-nonconforming. Gender identity refers to a person’s self-perception as male, female, both, genderqueer, or neither. Cisgender is an umbrella term used to describe people whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex, while transgender is a term used to describe people whose sense of personal identity does not correspond with their birth sex. Gender expression, or how one demonstrates gender (based on traditional gender role norms related to clothing, behaviour, and interactions) can be feminine, masculine, androgynous, or somewhere along a spectrum. Fluidity and uncertainty regarding sex and gender are especially common during early adolescence, when hormones increase and fluctuate creating difficulty of self-acceptance and identity achievement (Reisner et al., 2016, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019).

The Orientation and Identities diagram (see Figure 1) provides additional description and definition, along with a helpful resource that can be used to support a young person in mapping their identity and orientation using spectrums and can be an opportunity for rich discussion!

Gender identity, like vocational identity, is becoming an increasingly prolonged task as attitudes and norms regarding gender keep changing. The roles appropriate for males and females are evolving and some adolescents may foreclose on a gender identity as a way of dealing with this uncertainty by adopting more stereotypic male or female roles (Sinclair & Carlsson, 2013, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). Those that identify as transgender or other face even bigger challenges.

Gender Identity and Transgender Individuals

Individuals who identify with the role that is different from their biological sex are called transgender. According to Statistics Canada (2021) and the 2021 Census, one in 300 individuals in Canada over the age of 15 identify as transgender (0.19% of the population) or non-binary (0.14% of the population).

Transgender individuals may choose to alter their bodies through medical interventions such as surgery and hormonal therapy so that their physical being is better aligned with gender identity. They may also be known as male-to-female (MTF) or female-to-male (FTM). Not all transgender individuals choose to alter their bodies; many will maintain their original anatomy but may present themselves to society as another gender. This is typically done by adopting the dress, hairstyle, mannerisms, or other characteristic typically assigned to another gender. It is important to note that people who cross-dress, or wear clothing that is traditionally assigned to a different gender is not the same as identifying as trans. Cross-dressing is typically a form of self-expression, entertainment, or personal style, and it is not necessarily an expression against one’s assigned gender (APA 2008, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019).

After years of controversy over the treatment of sex and gender in the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (Drescher 2010), the most recent edition, DSM-5, responds to allegations that the term “gender identity disorder” is stigmatizing by replacing it with “gender dysphoria.” Gender identity disorder as a diagnostic category stigmatized the patient by implying there was something “disordered” about them. Gender dysphoria, on the other hand, removes some of that stigma by taking the word “disorder” out while maintaining a category that will protect patient access to care, including hormone therapy and gender reassignment surgery. In the DSM-5, gender dysphoria is a condition of people whose gender at birth is contrary to the one they identify with. For a person to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria, there must be a marked difference between the individual’s expressed/experienced gender and the gender others would assign him or her, and it must continue for at least six months. In children, the desire to be of the other gender must be present and verbalized (APA, 2013).

Studies show that people who identify as transgender are twice as likely to experience assault or discrimination as cisgender individuals; they are also one and a half times more likely to experience intimidation (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs 2010; Giovanniello 2013 as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). Trans women of colour are most likely be to victims of abuse. A practice called “deadnaming” by the American Civil Liberties Union, whereby trans people who are murdered are referred to by their birth name and gender, is a discriminatory tool that effectively erases a person’s trans identity and also prevents investigations into their deaths and knowledge of their deaths. Organizations such as the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs and Global Action for Trans Equality work to prevent, respond to, and end all types of violence against transgender and homosexual individuals. These organizations hope that by educating the public about gender identity and empowering transgender individuals, this violence will end.

Research on the topic of identity is ever-growing. Many researchers capture information in what’s known as an identity diagram, which highlights information such as religion, race, gender identity and expression, sexuality, and other topics that provide context and understanding for the various forms of identity in adolescents (Disability Thrive initiative, 2021). The LGBTQIA+ Wiki (n.d.) provides various resources for individuals specifically for the LGBTQ2SIA+ community.

Additional Resources

Want to learn more? See these resources for more information.

- Ethnic and racial identity development: ACT for youth

- Egale Canada – various resources for individuals who identify as LGBTQ2SIA+ and their allies (that’s us!)

- The Trevor Project – resources about gender diversity

- The519 – glossary of terms

Social Development during Adolescence

Parents

It appears that most teens do not experience adolescent “storm and stress“ to the degree once famously suggested by G. Stanley Hall, a pioneer in the study of adolescent development. Only small numbers of teens have major conflicts with their parents (Steinberg & Morris, 2001), and most disagreements are minor. For example, in a study of over 1,800 parents of adolescents from various cultural and ethnic groups, Barber (1994) found that conflicts occurred over day-to-day issues such as homework, money, curfews, clothing, chores, and friends. These disputes occur because an adolescent’s drive for independence and autonomy conflicts with the parent’s supervision and control. These types of arguments tend to decrease as teens develop (Galambos & Almeida, 1992 as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019).

As adolescents work to form their identities, they pull away from their parents, and the peer group becomes very important (Shanahan, McHale, Osgood, & Crouter, 2007 as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). Despite spending less time with their parents, most teens report positive feelings toward them (Moore, Guzman, Hair, Lippman, & Garrett, 2004 as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). Warm and healthy parent-child relationships have been associated with positive child outcomes, such as better grades and fewer school behaviour problems, in Canada as well as in other countries (Hair et al., 2005, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019).

Although peers take on greater importance during adolescence, family relationships remain important too. One of the key changes during adolescence involves a renegotiation of parent–child relationships. As adolescents strive for more independence and autonomy during this time, different aspects of parenting become more salient. For example, parents’ distal supervision and monitoring become more important as adolescents spend more time away from parents and in the presence of peers. Parental monitoring encompasses a wide range of behaviours such as parents’ attempts to set rules and know their adolescents’ friends, activities, and whereabouts, in addition to adolescents’ willingness to disclose information to their parents (Stattin & Kerr, 2000, as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). Psychological control, which involves manipulation and intrusion into adolescents’ emotional and cognitive world through invalidating adolescents’ feelings and pressuring them to think in particular ways is another aspect of parenting that becomes more salient during adolescence and is related to more problematic adolescent adjustment (Barber, 1996).

Peers

As children become adolescents, they usually begin spending more time with their peers and less time with their families, and these peer interactions are increasingly unsupervised by adults. Children’s notions of friendship often focus on shared activities, whereas adolescents’ notions of friendship increasingly focus on intimate exchanges of thoughts and feelings.

During adolescence, peer groups evolve from primarily single-sex to mixed-sex. Adolescents within a peer group tend to be similar to one another in behaviour and attitudes, which has been explained as being a function of homophily (adolescents who are similar to one another choose to spend time together in a “birds of a feather flock together” way) and influence (adolescents who spend time together shape each other’s behaviour and attitudes). Peer pressure is usually depicted as peers pushing a teenager to do something that adults disapprove of, such as breaking laws or using drugs. One of the most widely studied aspects of adolescent peer influence is known as deviant peer contagion (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011), which is the process by which peers reinforce problem behaviour by laughing or showing other signs of approval that then increase the likelihood of future problem behaviour. Although deviant peer contagion is more extreme, regular peer pressure is not always harmful. Peers can serve both positive and negative functions during adolescence. Negative peer pressure can lead adolescents to make riskier decisions or engage in more problematic behaviour than they would alone or in the presence of their family. For example, adolescents are much more likely to drink alcohol, use drugs, and commit crimes when they are with their friends than when they are alone or with their family. However, peers also serve as an important source of social support and companionship during adolescence, and adolescents with positive peer relationships are happier and better adjusted than those who are socially isolated or who have conflictual peer relationships. Crowds are an emerging level of peer relationships in adolescence. In contrast to friendships (which are reciprocal dyadic relationships) and cliques (which refer to groups of individuals who interact frequently), crowds are characterized more by shared reputations or images than actual interactions (Brown & Larson, 2009) These crowds reflect different prototypic identities (such as jocks or brains) and are often linked with adolescents’ social status and peers’ perceptions of their values or behaviours.

Developmental models focus on interpersonal contexts in both childhood and adolescence that foster depression and anxiety (e.g., Rudolph, 2009). Family adversity, such as abuse and parental psychopathology, during childhood sets the stage for social and behavioural concerns during adolescence. Adolescents with such problems generate stress in their relationships (e.g., by resolving conflict poorly and excessively seeking reassurance) and select into more maladaptive social contexts (e.g., “misery loves company” scenarios in which depressed youths select other depressed youths as friends and then frequently co-ruminate as they discuss their problems, exacerbating negative affect and stress). These processes are intensified for girls compared with boys because girls have more relationship-oriented goals related to intimacy and social approval, leaving them more vulnerable to disruption in these relationships. Anxiety and depression then exacerbate problems in social relationships, which in turn contribute to the stability of anxiety and depression over time.

References

ACT for youth. (n.d.) Ethnic and racial identity. https://actforyouth.net/adolescence/ethnic-racial-identity.cfm

American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™ (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development, 67, 3296–3319.

Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 74–103). New York, NY: Wiley.

Disability Thrive Initiative. (2021). Bridge the gap for the LGBTQ+ and disability communities. https://scdd.ca.gov/IDDThrive/

Dishion, T. J., & Tipsord, J. M. (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 189–214.

Egale Canada. (2023a). Affirming and inclusive language. https://egale.ca/awareness/affirming-and-inclusive-language/

Egale Canada. (2023b). Glossary of terms. https://egale.ca/awareness/glossary-of-terms-archived/

Egale Canada. (2023c). Resources. https://egale.ca/resources/#category=resources

Kim-Spoon, J., Longo, G.S., & McCullough, M.E. (2012) Parent-adolescent relationship quality as a moderator for the influence of parents’ religiousness on adolescents’ religiousness and adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(12), 1576-1587.

LGMTQIA Wiki. (n.d.). Identity diagrams. https://lgbtqia.fandom.com/wiki/Identity_diagrams

Lumen Learning. (2019). Lifespan development. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558.

Rudolph, K. D. (2009). The interpersonal context of adolescent depression. In S. Nolen-Hoeksema & L. M. Hilt (Eds.), Handbook of depression in adolescents (pp. 377–418). New York, NY: Taylor and Francis.

Statistics Canada. (2022). The Canadian census: A rich portrait of the country’s religious and ethnocultural diversity. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221026/dq221026b-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2021). Sex at birth and gender – 2021 Census promotional material. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/census/census-engagement/community-supporter/sex-birth-gender

The 519. (2020). The 519 glossary of terms. https://www.the519.org/education-training/glossary/

The Trevor Project. (n.d.) Resources about gender identity. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/resources/category/gender-identity/

OER Attributions:

Content from this chapter has been adapted from the following sources:

Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License/, except where otherwise noted.