- Strengthen communication skills. Many lessons about relationships and emotions start with the parent-child relationship. Effective and open communication lies at the heart of this relationship. Strong communication skills include being an attentive listener, sharing your experiences instead of lecturing, and asking open-ended questions.

- Build emotional vocabulary. State your feelings and discuss how other people may feel in a nonjudgmental way. Point out nonverbal cues such as body language when discussing emotions. Ask your teen, “How did you feel about that?” and “How do you think that made the other person feel?”

- Promote stress management skills. Encourage adolescents to handle stress in healthy ways. Daily management strategies include getting adequate sleep, staying active with exercise and hobbies, practicing deep breathing, and eating regular meals. Teach adolescents to “mind their brain”

by talking about adolescent brain development and letting them know how they can use the power of their brains to learn healthy behaviours.

by talking about adolescent brain development and letting them know how they can use the power of their brains to learn healthy behaviours. - Nurture self-regulation skills. Provide opportunities for adolescents to understand, express, and moderate their own feelings and behaviours. This step involves modeling self-regulation creating a warm and responsive environment, establishing consequences for poor decisions, and reducing the emotional intensity of conflicts.

- Limit exposure to risky situations. When faced with a decision, emotions may intermingle with recollections of what might have happened in the past. Prepare adolescents for risky situations by talking about what they can do to anticipate, avoid, and process them. Help adolescents weigh their emotions and think through short-term and long-term consequences.

- Help teens think carefully about risky situations. After a risky event, ask adolescents, “Why do you think this happened?” and “What could you do differently next time?” It may take them a long time to fully process their experiences so give them to time to think about the answers.

- Supporting a sense of purpose. Kaylin Ratner, an educational psychology professor at the University of Illinois, adds that “adolescents who feel a greater sense of purpose may be happier and more satisfied with life than peers who feel less purposeful” (Ratner, 2023, as cited in ScienceDaily, 2023) from the results of a recent study of over 200 adolescents.

Emotions and Emotion Regulation

Learning Objectives

- Compose a strength-based description of emotion regulation strategies for adolescents.

- Identify current trends for supporting emotional development for and with adolescents.

Introduction

With all the changes taking place in the brain, these can influence social and emotional experiences for adolescents! Our work as Child and Youth Care Practitioners (CYCPs) requires a thorough understanding of development, and how everything comes together. So far, we’ve learned about physical and cognitive development.

Now, we move into emotional development, and in particular, emotion regulation, which is key for adolescents. With changes in hormones and brain activity, come BIG emotions! How we support adolescents to understand and regulate these emotions is one of the many elements of our practice.

Recall from previous readings:

- Early in adolescence, cognitive developments result in greater self-awareness, the ability to think about abstract, future possibilities, and the ability to consider multiple possibilities and identities at once

- Changes in the levels of certain neurotransmitters (such as dopamine and serotonin) influence the way in which adolescents experience emotions, typically making them more emotional and more sensitive to stress

- When adolescents have advanced cognitive development and maturity, they tend to resolve identity issues more easily than peers who are less cognitively developed

As young people develop and grow, they learn more about themselves, gain independence, and expand their social circles beyond their family and caregivers. Their personalities are forming, and on top of all of this: hormones! Adolescents are facing strong emotions, changing peer relationships, more independence, expectations to be more adult-like, and a desire to take risks, all while lacking a fully mature brain or the life experience to navigate these situations. It is inevitable that some mistakes will occur along the way, as well as a great deal of learning. As CYCPs, we can learn about how to support in regulating these emotions. This includes understanding strength-based ways to describe strategies available, and knowing what to look for! Whether we create an activity or intervention, or use an evidence-informed current trend of what’s already available to us to adapt, all of this will factor into our work supporting young people and families.

Our expectations of behaviour and actions can sometimes clash with reality. We will explore social relationships in another week, but this reading will focus on the emotional aspect.

Brain development and emotions

There are many areas of the brain responsible for experiencing (and regulating emotions). In week 3 we explored the physical changes that take place, as well as the areas of the brain involved.

Review the reading to refresh your memory on the influence of hormones, and areas of the brain. but to recap:

Hormones are chemicals produced in the brain that lead to the physical changes that take place from the onset of puberty. Hormones such as estrogen, testosterone, or progesterone (to name a few) are directly responsible for this developmental time period; fluctuating hormones can directly impact mood and heighten emotional responses for adolescents, which can influence decision making (HHS, n.d.). With so many changes and surges of hormones, adolescents can often cycle through several emotions in a short period of time.

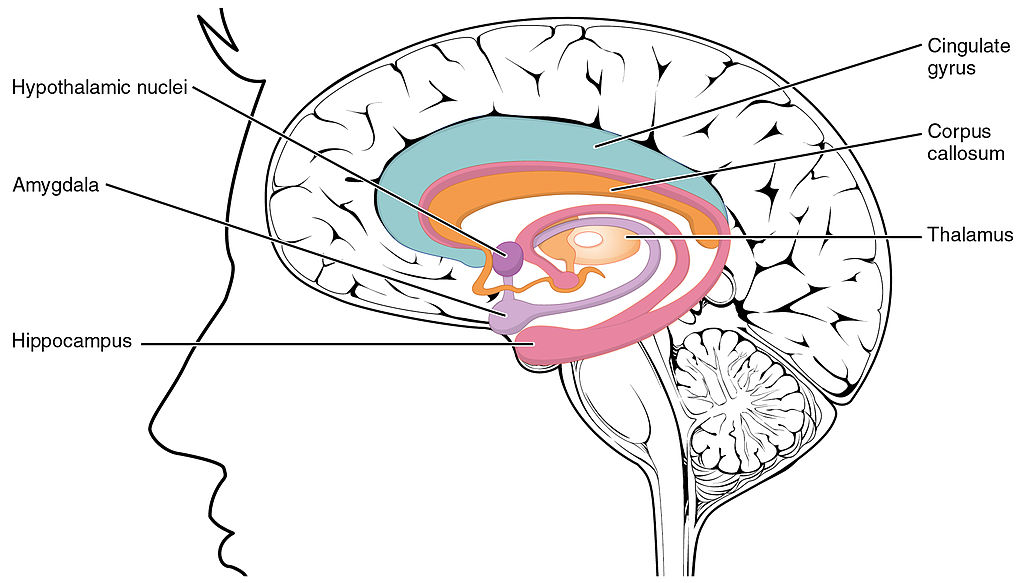

The area of the brain which is mainly responsible for emotional responses is the mid-brain (or limbic system) an area of “interconnected structures located deep within the brain” (Kapur & Seladi-Schulman, Eds., 2018; Romeo, 2013; Hartley & Somerville, 2015; Casey et al., 2005 as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). The authors state that while researchers and scientists are still learning about the full span of the limbic system, the following are currently the areas we know are involved:

- Hypothalamus – involved in controlling emotional responses (like the release of hormones like dopamine which then creates physical responses such as pleasure) as well as temperature regulation within the body

- Limbic system– an area of the brain that contains structures that support experiencing judgement, motivation, and mood (along with other areas of the brain

- Hippocampus – involved with the retrieval and storage of memories, as well as understanding spatial dimensions of the environment

- Amygdala – supports the coordination of how we respond to environmental triggers of an emotional response, mainly anger and fear

Image 3: Cross-sectional diagram of the limbic system

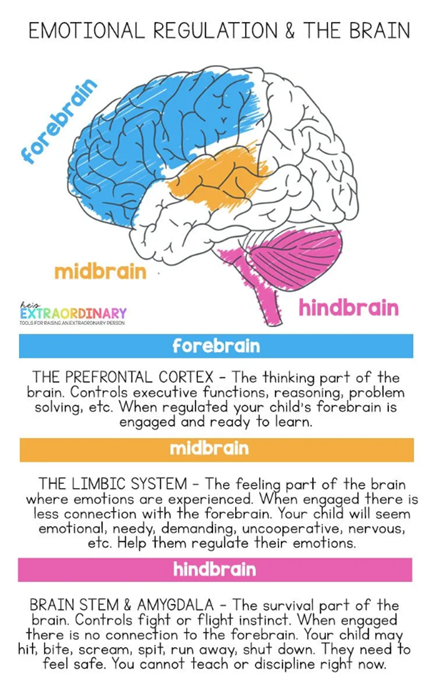

The limbic system develops years ahead of the prefrontal cortex. Development in the limbic system plays an important role in determining rewards and punishments and processing emotional experience and social information. Pubertal hormones target the amygdala directly and powerful sensations become compelling (Romeo, 2013 as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). Brain scans confirm that cognitive control, revealed by fMRI studies, is not fully developed until adulthood because the prefrontal cortex is limited in connections and engagement (Hartley & Somerville, 2015 as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019). Recall that this area is responsible for judgment, impulse control, and planning, and it is still maturing into early adulthood (Casey, Tottenham, Liston, & Durston, 2005 as cited in Lumen Learning, 2019).

Additionally, changes in both the levels of the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin in the limbic system make adolescents more emotional and more responsive to rewards and stress. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter in the brain associated with pleasure and attuning to the environment during decision-making. During adolescence, dopamine levels in the limbic system increase and input of dopamine to the prefrontal cortex increases. The increased dopamine activity in adolescence may have implications for adolescent risk-taking and vulnerability to boredom. Serotonin is involved in the regulation of mood and behaviour. It affects the brain in a different way. Known as the “calming chemical,” serotonin eases tension and stress. Serotonin also puts a brake on the excitement and sometimes recklessness that dopamine can produce. If there is a defect in the serotonin processing in the brain, impulsive or violent behaviour can result.

When the overall brain chemical system is working well, it seems that these chemicals interact to balance out extreme behaviours. But when stress, arousal or sensations become extreme, the adolescent brain is flooded with impulses that overwhelm the prefrontal cortex, and as a result, adolescents engage in increased risk-taking behaviours and emotional outbursts possibly because the frontal lobes of their brains are still developing.

The human brain attempts to address these (among other stressors) by activating chemicals such as cortisol (a stress hormone) and other activity in the nervous system which cause an individual to respond to the pressure in the moment (e.g., the flight, fight, or freeze response).

Later in adolescence, the brain’s cognitive control centers in the prefrontal cortex develop, increasing adolescents’ self-regulation and future orientation. The difference in timing of the development of these different regions of the brain contributes to more risk taking during middle adolescence because adolescents are motivated to seek thrills that sometimes come from risky behaviour, such as reckless driving, smoking, or drinking, and have not yet developed the cognitive control to resist impulses or focus equally on the potential risks (Steinberg, 2008). One of the world’s leading experts on adolescent development, Laurence Steinberg, likens this to engaging a powerful engine before the braking system is in place. The result is that adolescents are more prone to risky behaviours than are children or adults.

Because we are still learning more about the brain, and how little we actually know about emotions during adolescence, this has prompted researchers to examine how adolescents process emotions, and if they process them in the same way as adults. Deborah Yurgelun-Todd and a group of researchers have studied how adolescents perceive emotion as compared to adults. Adults and teens were shown pictures of adult faces and asked to identify the emotion expressed. Using fMRI, the researchers traced the part of the brain responded as subjects were asked to identify the expression depicted in the picture.

The adults correctly identified the emotions expressed in the pictures, but the teens misinterpreted the expressions. The teens and adults also used different parts of their brains to process the information. The fMRI showed the amygdala most active in teens. This mid-brain structure guides instinctual or “gut” reactions. In adults, the frontal cortex, which governs reason and planning, was active during this exercise.

As the teens got older, the center of activity shifted more toward the frontal cortex and away from the amygdala (Inside the Teenage Brain, Frontline, PBS).

Emotional changes during adolescence

With everything taking place in the brain, there are many ways that emotions can be displayed in the lives of teenagers. HealthLinkBC (2014) describe emotional changes we may notice such as strong, intense emotions, where moods may seem unpredictable. They also describe the teen:

- is more sensitive to [the] emotions of others: young people get better at reading and processing other people’s emotions as they get older. While they’re developing these skills, they can sometimes misread facial expressions or body language

- is more self-conscious, especially about physical appearance and changes. Teenage self-esteem is often affected by appearance – or by how teenagers think they look. As they develop, teens might compare their bodies with those of friends and peers

- goes through a “invincible” stage of thinking and acting as if nothing bad could happen to him. Your child’s decision-making skills are still developing, and your child is still learning about the consequences of actions.

What can impact emotions?

Beyond emotions and hormones, there are many things that can impact or affect emotions. These influences can then lead to the development of mental health concerns such as anxiety, depression, or other concerns such as self-harm (which you have and will learn about in your mental health courses).

Some things that can have an impact on emotions and mental health:

- Social media use (Dowlan, 2019; McKenna, 2019)

- Cell phones (Damour, 2017 as cited in CBS News, 2017)

- Watching television Dowlan, 2019; McKenna, 2019)

- Stress (HHS, n.d.)

- Risk factors (see our reading on the social determinants of health)

- Negative or detrimental influences within the ecological system (see our reading on theory reviews, week 2)

- e.g., negative relationships with caregivers, peers (Barber, 1996)

- Self-image, identity, and self-esteem (see our reading from week 6)

- Being manipulated and/or have emotions invalidated (Barber, 1996)

The global pandemic is one example of a significant negative impact on young people within the chronosystem, which in turn impacts emotions. UNICEF Canada (2021) conducted polls with youth, who found that “nearly two-thirds of youth polled… said the pandemic has negatively impacted their mental health.” UNICEF Canada (2021) found that the effects of the pandemic will continue to impact mental health and well-being for “many years to come.”

There are many other influences on emotion, but they go beyond the scope of this course. We continue to explore emotions. The list of what can impact emotions is long but not exhaustive. Having said that, are all emotions a negative experience? Feelings are HARD! – but is that always a bad thing? Not according to some researchers, such as Lisa Damour, a clinical psychologist, author, and podcast host, who has found that strong emotions are ‘a feature’ but not always a negative experience for adolescents (Stevens, 2023; Strauss, 2023).

Because the adolescent brain isn’t quite fully developed, this stress response activates much faster for adolescents than for adults. Having said that, not all stress is negative. New and exciting experiences, such as getting your driver’s license, going for an interview, starting a new job, doing well on an exam, can also trigger hormonal responses that support the adolescent to focus and be more alert. Damour shares that “not only are sadness and worrying healthy and natural parts of being a teenager, but the ability to experience these feelings (without a parent panicking) and to learn how to cope with them is developmentally necessary” (Stevens, 2023).

Emotion Regulation

There are so many ways that we as CYCPs can support healthy emotion regulation for teens. And children. And families. Well… anyone, really! Utilizing our strength-based approach can support with focusing on opportunities, rather than only deficits or concerns. The ability to regulate emotions, and how they impact us, is a skill learned over time. Previous generations did not have the luxury of being taught this in school, but as research emerges and time goes by, emotion regulation is becoming more mainstream.

When planning activities or interventions, CYCPs need context, an understanding of where a behaviour might stem from. Whether emotions are positive, neutral, or negative, supporting a teen’s understanding of what’s happening for them may support emotional maturity, and the ability to regulate these emotions. First, we’ll explore some suggestions in a broader context.

How else CYCPs can support emotion regulation

By now, you’re probably asking yourself: How can we as CYCPs support emotion regulation?

Having an appreciation for where an adolescent is at, their understanding, knowing their strengths, and having trust and a solid therapeutic relationship are all a good start. With all this information, we can develop activities and interventions to bring awareness of what emotions a young person may be feeling, and how to regulate. HHS (2014) share additional suggestions to support emotional development, for caregivers, educators, CYCPs, and other adults that work alongside adolescents:

There are two areas we can further explore, in our support of healthy emotion regulation: First, we need to understand behaviour, (by way of functional behavioural assessments) and then, we can look to social and emotional learning.

Understanding behaviour: context

Functional behavioural assessments look beyond observable behaviour and examine what function the behaviour may be serving (Mauro, n.d. as cited in Melrose et al., 2015). Knowing what is valuable, important, and reinforcing to individuals can help caregivers support their clients toward alternative ways of behaving that will still meet client needs.

Functional behaviour analysis helps us understand why people continue injuring themselves or being aggressive. Three common reasons for any behaviour are that it:

- Provides an escape from something a person does not like, such as demands from an authority figure (O’Neill et al., 1997 as cited in Melrose et al., 2015

- Provides access to something a person does like, such as attention (Iwata, 1982; 1994 as cited in Melrose et al., 2015)

- Provides stimulation that a person can create when they are alone

When an individual needs to escape from an activity that is difficult or unpleasant, providing a break may help. When they need access to something they value, such as favourite people, food, or activities, providing this access before challenging behaviour begins may prevent the challenging behaviour from occurring. When people are alone and they need stimulation, they can be given alternatives through opportunities for them to see, hear, smell, touch, and taste.

It may be useful to think of these behaviours as a form of self-expression and a way of communicating needs, such as “I want attention” or “I need a break.” Viewing challenging behaviours through the lens of behavioural analysis, self-injuring behaviour may indicate a need for sensory stimulation, and aggressive behaviour may indicate a need for social reinforcement.

When incorporating this with a strength-based perspective, we can identify what items the individual prefers, what they enjoy and do well with, and then ensuring that these items are made available. Research has shown this strategy can substantially decrease self-injury (Lindauer, DeLeon, & Fisher, 1999; Smith et. al, 1993; Vollmer, Marcus, & LeBlanc, 1994 as cited in Melrose et al., 2015). Environmental enrichment is the least labour intensive of all interventions.

Think about it: How well do you do in an environment that meets your needs?

Although most CYCPs are not expected to implement functional behavioural assessments with their young people and families, understanding the thinking behind this tool can make an important difference in providing evidence-informed care. Morris (n.d. as cited in Melrose, Dusome, Simpson, Crocker & Athens, 2015) identified the ABCs of functional behavioural assessments as Analysis, Behaviour, and Consequence. Analysis occurs when professionals direct the client to perform an action to identify existing or previous behaviour. Behaviour is the response from the client: successful performance, non-compliance, or no response. Consequence is the therapist’s response “which can range from strong positive reinforcement (e.g., a special treat, verbal praise) to a strong negative response, such as ‘No!’” (Morris, n.d. as cited in Melrose et al., 2015). When behavioural analysts implement functional behavioural assessments, these ABCs ground their thinking.

This understanding provide us context. Once we know the wat, we can move on to the how. How we use this information as CYCPs can best be summarized through social and emotional learning.

Social Emotional Learning

One emerging area that directly addresses emotion regulation, is Social and Emotional Learning (SEL; ACT for Youth, 2023; Shanker, 2014). Social development and emotional development are more intricate and interconnected than previously understood. As a result of the dynamics that take place, SEL has emerged as one way to understand functioning and psychological wellbeing (Shanker, 2014) from a strengths-based perspective.

ACT for Youth (2023) describes SEL as “a student-centered approach that emphasizes building on students’ strengths; developing skills through hands-on, experiential learning; giving young people voice in the learning process; and supporting youth through positive relationships with adults over an extended period of time. Commonly used in school and after-school settings, SEL programming offers strategies and techniques helpful to other youth work professionals.” Doesn’t that sound like it fits right in with CYC practice?

Research conducted since the early 2000s has established “five core aspects of social-emotional functioning thought to be critical for a child’s wellbeing and educational attainment” (Shanker, 2014, p. 4). The five core aspects are:

1. Self-awareness

2. Self-management

3. Social awareness

4. Interpersonal relations

5. Decision-making

This movement has led to the understanding that “the better students can identify and describe their feelings, deal with stress and manage their emotions, empathize with others, develop strong friendships, and have good problem-solving strategies, the better their outcomes in all respects” (Shanker, 2014, p. 17). This all leads to emotion regulation!

Learn more about SEL: Resources

Check out Act for Youth’s SEL toolkit: https://actforyouth.net/youth_development/professionals/sel/

Read Shanker’s (2014) Report: https://peopleforeducation.ca/report/sel-domain-paper/

References

Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development, 67, 3296–3319.

CBS News. (2017). New study links phone use and mental health issues in teens. https://www.cbsnews.com/video/new-study-links-phone-use-and-mental-health-issues-in-teens/

Dowlan, E. W. (2019). Social media and television use — but not video games — predict depression and anxiety in teens. https://www.psypost.org/2019/12/social-media-and-television-use-but-not-video-games-predict-depression-and-anxiety-in-teens-55045

HealthLinkBC. (2014). Social and emotional changes. https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/pregnancy-parenting/parenting-teens-12-18-years/caring-your-teen/social-and-emotional-changes

HHS. (n.d.) Emotional development. https://opa.hhs.gov/adolescent-health/adolescent-development-explained/emotional-development

PBS (n.d.). Frontline: Inside the Teenage Brain. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/teenbrain/

McKenna, K. (2019). Social media, but not video games, linked to depression in teens, according to Montreal study. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/social-media-mental-health-screen-time-instagram-facebook-video-games-study-1.5211782

Melrose, S., Dusome, D., Simpson, J., Crocker, C., & Athens, E. (2015). Supporting Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities & Mental Illness. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/caregivers

ScienceDaily. (2014). A sense of purpose may have significant impact on teens’ emotional well-being. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2023/02/230213201032.htm

Shanker, S. (2014). Broader measures for success: Social/Emotional Learning. In Measuring What Matters, People for Education. Toronto: November 8, 2014.

Stevens, H. (2023). Powerful emotions are ‘a feature, not a bug’ for teens. New book helps navigate them with grace and humanity. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/heidi-stevens-powerful-emotions-are-a-feature-not-a-bug-for-teens-new-book-helps-navigate-them-with-grace-and-humanity/ar-AA18rZCO

Strauss, E. (2023). Why hard feelings are good for teens. https://www.cnn.com/2023/02/20/health/teens-healthy-feelings-wellness/index.htm

UNICEF Canada. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on poor mental health in children and young people ‘tip of the iceberg.’ https://www.unicef.ca/en/press-release/impact-covid-19-poor-mental-health-children-and-young-people-tip-iceberg-unicef

OER Attributions:

Content from this chapter has been adapted from the following sources:

Adolescent Psychology by Lumen Learning (2020) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Supporting Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities & Mental Illness by Sherri Melrose, Debra Dusome, John Simpson, Cheryl Crocker, Elizabeth Athens is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.