Emerging Adulthood

Introduction

Emerging adulthood is a unique life stage which includes individuals who are between 18 and 25 years of age (Arnett, 2000, 2010, 2015, 2025). In some contexts, this can go up to age 29 (Society for the Study of Emerging Adulthood, 2025). This unique age group is culturally relevant to Western and other industrialized societies where it is common for emerging adults to be enrolled in post-secondary education, such as college or university (Arnett, 2000, 2010, 2015, 2025).

The period of emerging adulthood is described as vastly different from adolescence (Arnett, 2000; Kail & Zolner, 2021) and adulthood, as a period of identity formation and exploration where an individual tries out various roles and possibilities that will become solidified into adulthood (Arnett, 2015).

Individuals in this age range are described as feeling in-between, experiencing instability (Arnett, 2015; Arnett, Kloep, Hendry & Tanner, 2015) which can have an impact on success in education, as emerging adults can have a wide range of responsibilities and changes that can divide their attention.

Five features make emerging adulthood distinctive:

- identity explorations

- instability,

- self-focus,

- feeling in-between adolescence and adulthood

- sense of broad possibilities for the future

Emerging adulthood is found mainly in industrialized countries, where most young people obtain tertiary education and median ages of entering marriage and parenthood are around 30. There are variations in emerging adulthood within industrialized countries. It lasts longest in Europe, and in Asian industrialized countries, the self-focused freedom of emerging adulthood is balanced by obligations to parents and by conservative views of sexuality. In non-industrialized countries, although today emerging adulthood exists only among the middle-class elite, it can be expected to grow in the 21st century as these countries become more affluent.

Learning Objectives

- Expand on areas of development between adolescence and adulthood.

- Identify differences between the age group of adolescence and adulthood.

- Debate the theory of Emerging Adulthood.

Identity and development – school, work, and life

Think for a moment about the lives of your grandparents and great-grandparents when they were in their twenties. How do their lives at that age compare to your life? If they were like most other people of their time, their lives were quite different than yours. What happened to change the twenties so much between their time and our own? And how should we understand the 18–25 age period today?

The median marriage age for men was around 22, and married couples usually had their first child about one year after their wedding day. All told, for most young people half a century ago, their teenage adolescence led quickly and directly to stable adult roles in love and work by their late teens or early twenties. These roles would form the structure of their adult lives for decades to come.

Emerging adulthood is also a self-focused age. Most American emerging adults move out of their parents’ home at age 18 or 19 and do not marry or have their first child until at least their late twenties (Arnett, 2004). Even in countries where emerging adults remain in their parents’ home through their early twenties, as in Canada, southern Europe and in Asian countries such as Japan, they establish a more independent lifestyle than they had as adolescents (Rosenberger, 2007). Emerging adulthood is a time between adolescents’ reliance on parents and adults’ long-term commitments in love and work, and during these years, emerging adults focus on themselves as they develop the knowledge, skills, and self-understanding they will need for adult life. In the course of emerging adulthood, they learn to make independent decisions about everything from what to have for dinner to whether or not to get married.

Another distinctive feature of emerging adulthood is that it is an age of feeling in-between, not adolescent but not fully adult, either. When asked, “Do you feel that you have reached adulthood?” the majority of emerging adults respond neither yes nor no but with the ambiguous “in some ways yes, in some ways no” (Arnett, 2003, 2012). It is only when people reach their late twenties and early thirties that a clear majority feels adult. Most emerging adults have the subjective feeling of being in a transitional period of life, on the way to adulthood but not there yet. This “in-between” feeling in emerging adulthood has been found in a wide range of countries, including Argentina (Facio & Micocci, 2003), Austria (Sirsch, Dreher, Mayr, & Willinger, 2009), Israel (Mayseless & Scharf, 2003), the Czech Republic (Macek, Bejček, & Vaníčková, 2007), and China (Nelson & Chen, 2007).

Education

Now, all that has changed. A higher proportion of young people than ever before pursue education and training beyond secondary school, including college or university credentials, the highest percentage among G7 countries (Statistics Canada, 2022a).

Now, all that has changed. A higher proportion of young people than ever before pursue education and training beyond secondary school, including college or university credentials, the highest percentage among G7 countries (Statistics Canada, 2022a).

Statistics also show that almost “one in four Canadians (24.6%) had a college certificate or diploma or similar credential as their highest level of education in 2021, above all other G7 countries and more than double the share in the United States (10.8%)” (Statistics Canada, 2022a). I love that college is included in these numbers, woo hoo!!

The explorations of emerging adulthood also make it the age of instability. As emerging adults explore different possibilities in love and work, their lives are often unstable, making it challenging to live independently. Building on identity development from adolescence, this instability ties in to

Living arrangements

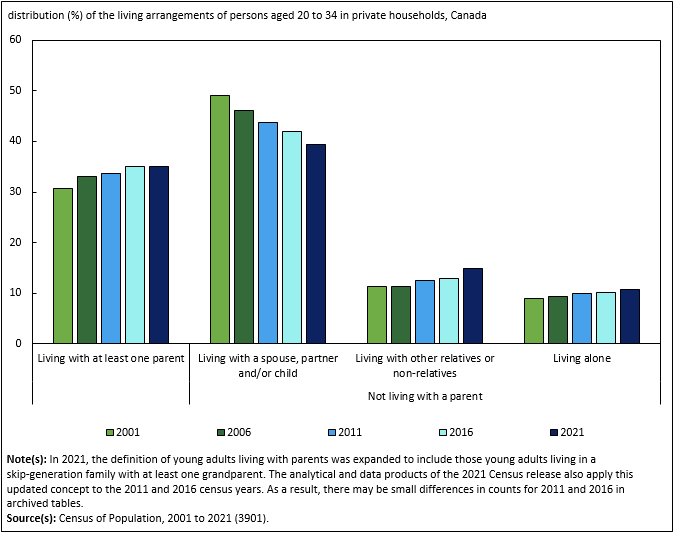

See the following excerpt from the 2021 census data which summarizes the percentage of individuals ages 20-34 and where they live. According to the census data, 35.1% of young adults between 20 and 34 are living with at least one of their parents.

In 2021, 61% of young people live with at least one parent, a roommate, or live alone. What are your thoughts? Why might this be?

Umay Kader, completing her PhD in sociology at University of British Columbia believes that factors contributing to these statistics include “housing crises, the labour market—especially the uncertain and precarious labour market—unemployment and underemployment” (Source). “After trending upward since 2001 (31%), the share of young adults aged 20 to 34 living in the same household as at least one of their parents was unchanged from 2016 to 2021 (35%). However, the age profile of young adults who lived with their parents continued to shift to older ages: in 2021, 46% of young adults who lived with their parents were aged 25 to 34, compared with 38% in 2001” (Statstics Canada, 2022b).

Finally, emerging adulthood is the age of possibilities, when many different futures remain possible, and when little about a person’s direction in life has been decided for certain. It tends to be an age of high hopes and great expectations, in part because few of their dreams have been tested in the fires of real life. In one national survey of 18- to 24-year-olds in the United States, nearly all—89%—agreed with the statement, “I am confident that one day I will get to where I want to be in life” (Arnett & Schwab, 2012). This optimism in emerging adulthood has been found in other countries as well (Nelson & Chen, 2007).

International Variations

The five features proposed in the theory of emerging adulthood originally were based on research involving about 300 Americans between ages 18 and 29 from various ethnic groups, social classes, and geographical regions (Arnett, 2004). To what extent does the theory of emerging adulthood apply internationally? Would this apply to Canada?

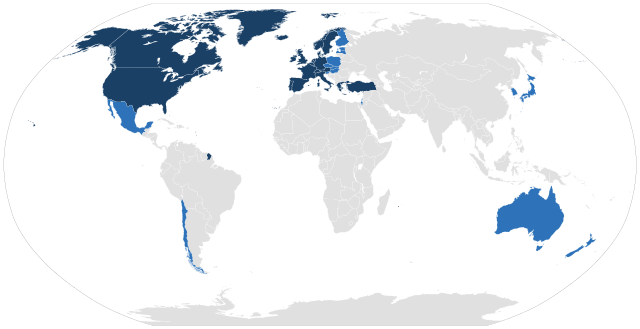

The answer to this question depends greatly on what part of the world is considered. Demographers make a useful distinction between the non-industrialized countries that comprise the majority of the world’s population and the industrialized countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), including the United States, Canada, western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The current population of OECD countries (also called industrialized countries) is 1.2 billion, about 18% of the total world population (UNDP, 2011). The rest of the human population resides in non-industrialized countries, which have much lower median incomes; much lower median educational attainment; and much higher incidence of illness, disease, and early death. Let us consider emerging adulthood in OECD countries first, then in non-industrialized countries.

Theories of Emerging Adult Psychosocial Development

Why do we need another theory? Think about the different areas of development. What happens once adolescents reach age 18? Are they fully adults? Age, maturity, and development – are they just social constructs? Recall what you know about the different theories.

Erikson’s Theory

| Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages of Development | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | Age (years) | Developmental Task | Description |

| 1 | 0–1 | Trust vs. mistrust | Trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met |

| 2 | 1–3 | Autonomy vs. shame/doubt | Develop a sense of independence in many tasks |

| 3 | 3–6 | Initiative vs. guilt | Take initiative on some activities—may develop guilt when unsuccessful or boundaries overstepped |

| 4 | 7–11 | Industry vs. inferiority | Develop self-confidence in abilities when competent or sense of inferiority when not |

| 5 | 12–18 | Identity vs. confusion | Experiment with and develop identity and roles |

| 6 | 19–29 | Intimacy vs. isolation | Establish intimacy and relationships with others |

| 7 | 30–64 | Generativity vs. stagnation | Contribute to society and be part of a family |

| 8 | 65– | Integrity vs. despair | Assess and make sense of life and meaning of contributions |

Intimacy vs. Isolation (Love)

Erikson (1950) believed that the main task of early adulthood is to establish intimate relationships and not feel isolated from others. Intimacy does not necessarily involve romance; it involves caring about another and sharing one’s self without losing one’s self. This developmental crisis of “intimacy versus isolation” is affected by how the adolescent crisis of “identity versus role confusion” was resolved (in addition to how the earlier developmental crises in infancy and childhood were resolved). The young adult might be afraid to get too close to someone else and lose her or his sense of self, or the young adult might define her or himself in terms of another person. Intimate relationships are more difficult if one is still struggling with identity. Achieving a sense of identity is a life-long process, but there are periods of identity crisis and stability. And, according to Erikson, having some sense of identity is essential for intimate relationships. Although, consider what that would mean for previous generations of women who may have defined themselves through their husbands and marriages, or for Eastern cultures today that value interdependence rather than independence.

People in early adulthood (the 20s through 40) are concerned with intimacy vs. isolation. After we have developed a sense of self in adolescence, we are ready to share our life with others. However, if other stages have not been successfully resolved, young adults may have trouble developing and maintaining successful relationships with others. Erikson said that we must have a strong sense of self before we can develop successful intimate relationships. Adults who do not develop a positive self-concept in adolescence may experience feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation.

Friendships as a source of intimacy

In our twenties, intimacy needs may be met in friendships rather than with partners. This is especially true in the United States today as many young adults postpone making long-term commitments to partners either in marriage or in cohabitation. The kinds of friendships shared by women tend to differ from those shared by men (Tannen, 1990). Friendships between men are more likely to involve sharing information, providing solutions, or focusing on activities rather than discussing problems or emotions. Men tend to discuss opinions or factual information or spend time together in an activity of mutual interest. Friendships between women are more likely to focus on sharing weaknesses, emotions, or problems. Women talk about difficulties they are having in other relationships and express their sadness, frustrations, and joys. These differences in approaches could lead to problems when men and women come together. She may want to vent about a problem she is having; he may want to provide a solution and move on to some activity. But when he offers a solution, she thinks he does not care! Effective communication is the key to good relationships.

Many argue that other-sex friendships become more difficult for heterosexual men and women because of the unspoken question about whether the friendships will lead to a romantic involvement. Although common during adolescence and early adulthood, these friendships may be considered threatening once a person is in a long-term relationship or marriage. Consequently, friendships may diminish once a person has a partner or single friends may be replaced with couple friends.

Personality

Beyond providing insights into the general outline of adult personality development, Roberts et al. (2006) found that young adulthood (the period between the ages of 18 and the late 20s) was the most active time in the lifespan for observing average changes, although average differences in personality attributes were observed across the lifespan. Such a result might be surprising in light of the intuition that adolescence is a time of personality change and maturation. However, young adulthood is typically a time in the lifespan that includes a number of life changes in terms of finishing school, starting a career, committing to romantic partnerships, and parenthood (Donnellan, Conger, & Burzette, 2007; Rindfuss, 1991). Finding that young adulthood is an active time for personality development provides circumstantial evidence that adult roles might generate pressures for certain patterns of personality development. Indeed, this is one potential explanation for the maturity principle of personality development.

It should be emphasized again that average trends are summaries that do not necessarily apply to all individuals. Some people do not conform to the maturity principle. The possibility of exceptions to general trends is the reason it is necessary to study individual patterns of personality development. The methods for this kind of research are becoming increasingly popular (e.g., Vaidya, Gray, Haig, Mroczek, & Watson, 2008) and existing studies suggest that personality changes differ across people (Roberts & Mroczek, 2008). These new research methods work best when researchers collect more than two waves of longitudinal data covering longer spans of time. This kind of research design is still somewhat uncommon in psychological studies but it will likely characterize the future of research on personality stability.

We have learned from Erikson that the psychosocial developmental task of early adulthood is “intimacy versus isolation” and if resolved relatively positively, it can lead to the virtue of “love.” In this section, we will look more closely at relationships in early adulthood, particularly in terms of love, dating, cohabitation, marriage, and parenting.

We have learned from Erikson that the psychosocial developmental task of early adulthood is “intimacy versus isolation” and if resolved relatively positively, it can lead to the virtue of “love.” In this section, we will look more closely at relationships in early adulthood, particularly in terms of love, dating, cohabitation, marriage, and parenting.Attachment Theory in Adulthood

The need for intimacy, or close relationships with others, is universal and persistent across the lifespan. What our adult intimate relationships look like actually stems from infancy and our relationship with our primary caregiver (historically our mother)—a process of development described by attachment theory, which you learned about in the module on infancy. Recall that according to attachment theory, different styles of caregiving result in different relationship “attachments.”

For example, responsive mothers—mothers who soothe their crying infants—produce infants who have secure attachments (Ainsworth, 1973; Bowlby, 1969). About 60% of all children are securely attached. As adults, secure individuals rely on their working models—concepts of how relationships operate—that were created in infancy, as a result of their interactions with their primary caregiver (mother), to foster happy and healthy adult intimate relationships. Securely attached adults feel comfortable being depended on and depending on others.

As you might imagine, inconsistent or dismissive parents also impact the attachment style of their infants (Ainsworth, 1973), but in a different direction. In early studies on attachment style, infants were observed interacting with their caregivers, followed by being separated from them, then finally reunited. About 20% of the observed children were “resistant,” meaning they were anxious even before, and especially during, the separation; and 20% were “avoidant,” meaning they actively avoided their caregiver after separation (i.e., ignoring the mother when they were reunited). These early attachment patterns can affect the way people relate to one another in adulthood. Anxious-resistant adults worry that others don’t love them, and they often become frustrated or angry when their needs go unmet. Anxious-avoidant adults will appear not to care much about their intimate relationships and are uncomfortable being depended on or depending on others themselves.

| Table 1. Types of Early Attachment and Adult Intimacy | |

| Secure | “I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t often worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me,” |

| Anxious-avoidant | “I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, love partners want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being.” |

| Anxious-resistant | “I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t want to stay with me. I want to merge completely with another person, and this desire sometimes scares people away.” |

The good news is that our attachment can be changed. It isn’t easy, but it is possible for anyone to “recover” a secure attachment. The process often requires the help of a supportive and dependable other, and for the insecure person to achieve coherence—the realization that his or her upbringing is not a permanent reflection of character or a reflection of the world at large, nor does it bar him or her from being worthy of love or others of being trustworthy (Treboux, Crowell, & Waters, 2004).

You can watch this video “What is Your Attachment Style?” from The School of Life to learn more.

Conclusion

The new life stage of emerging adulthood has spread rapidly in the past half-century and is continuing to spread. Now that the transition to adulthood is later than in the past, is this change positive or negative for emerging adults and their societies? Certainly, there are some negatives. It means that young people are dependent on their parents for longer than in the past, and they take longer to become fully contributing members of their societies. A substantial proportion of them have trouble sorting through the opportunities available to them and struggle with anxiety and depression, even though most are optimistic. However, there are advantages to having this new life stage as well. By waiting until at least their late twenties to take on the full range of adult responsibilities, emerging adults are able to focus on obtaining enough education and training to prepare themselves for the demands of today’s information- and technology-based economy. Also, it seems likely that if young people make crucial decisions about love and work in their late twenties or early thirties rather than their late teens and early twenties, their judgment will be more mature and they will have a better chance of making choices that will work out well for them in the long run.

What can we do to enhance the likelihood that emerging adults will make a successful transition to adulthood? Thinking about the young people we work with, and their needs, look at the various systems they might interact with. Justice, education, community, etc. What can we support? How can we advocate, and encourage self-advocacy? What barriers exist, and how can we address them? One example: Across the world, societies would be wise to strive to make it possible for every emerging adult to attend post-secondary education, free of charge. There could be no better investment for preparing young people for the economy of the future.

References

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469-480.

Arnett, J. J., Kloep, M., Hedry, L.B., & Tanner, J. L. (2011). Debating Emerging Adulthood: Stage or process? New York: Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J. (2015). Emerging Adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (2nd ed). New York: Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J. (2025). Emerging adulthood. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/3vtfyajs

Kail, R. V., & Zolner, T. (2021). Children: A Chronological Approach. (6th Canadian Ed.). Pearson Canada.

Society for the Study of Emerging Adulthood. (2025). About. Retrieved from https://www.ssea.org/

Statistics Canada. (2022a). Home alone: More persons living solo than ever before, but roomies the fastest growing household type. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220713/dq220713a-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2022b). Canada leads the G7 for the most educated workforce, thanks to immigrants, young adults and a strong college sector, but is experiencing significant losses in apprenticeship certificate holders in key trades. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221130/dq221130a-eng.htm

OER Attributions

Lifespan Development by Julie Lazzara is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Emerging Adulthood by Jeffrey Jensen Arnett is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.