Cognitive and Moral Development

Cognitive and Moral Development in Adolescence

Learning Objectives

- Review Piaget’s ‘Stages of Development’

- Discuss formal operational thought

- Identify Kohlberg’s theory of moral development

Adolescence is a time of rapid cognitive development. During adolescence, biological changes in brain structure and connectivity in the brain interact with increased experience, knowledge, and changing social demands to produce rapid cognitive growth. These changes generally begin at puberty or shortly thereafter, and some skills continue to develop as an adolescent ages. Development of executive functions, or cognitive skills that enable the control and coordination of thoughts and behaviour, are generally associated with the prefrontal cortex area of the brain. This area of the brain is the last to develop, typically developing until age 25.

Improvements in basic thinking abilities generally occur in several areas during adolescence:

- Attention: Improvements are seen in selective attention (the process by which one focuses on one stimulus while tuning out another), as well as divided attention (the ability to pay attention to two or more stimuli at the same time).

- Memory: Improvements are seen in working memory and long-term memory.

- Processing Speed: Adolescents think more quickly than children. Processing speed improves sharply between age five and middle adolescence, levels off around age 15, and does not appear to change between late adolescence and adulthood.

- Organization: Adolescents are more aware of their own thought processes and can use mnemonic devices and other strategies to think and remember information more efficiently.

- Metacognition: Adolescents can think about thinking itself. This often involves monitoring one’s own cognitive activity during the thinking process. Metacognition provides the ability to plan ahead, see the future consequences of an action, and provide alternative explanations of events.

The changes in how adolescents think, reason, and understand can be even more dramatic than their obvious physical changes. This stage of cognitive development, termed by Piaget as the formal operational stage, marks a movement from the ability to think and reason logically only about concrete, visible events to an ability to also think logically about abstract concepts.

Adolescents are now able to analyze situations logically in terms of cause and effect and to entertain hypothetical situations and entertain what-if possibilities about the world. This higher-level thinking allows them to think about the future, evaluate alternatives, and set personal goals. Although there are marked individual differences in cognitive development among teens, these new capacities allow adolescents to engage in the kind of introspection and mature decision making that was previously beyond their cognitive capacity.

Importance for CYCPs

The thoughts, ideas, and concepts developed during this period of life greatly influence one’s future life and play a major role in character and personality formation. When working with young people, Child and Youth Care Practitioners (CYCPs) can use this information when developing relationships, activities, and interventions to be able to adjust to individual abilities and strengths, and support continued development into adulthood.

Cognitive Development During Adolescence

Piaget was one of the first theorists to map out and describe the ways in which children’s thought processes differ from those of adults. More specifically he identified that children of differing ages interpreted the world differently. He stressed that cognitive development occurs through constant interaction between their maturation and their experiences of the world. This interaction piece represented new thinking. Piaget believed that children were naturally curious. They want to make sense of their experiences, and in doing so, construct their understanding of the world. They are like scientists and construct theories about the world. Of course, these theories are often incomplete but they help them to reach more advanced levels of maturation. The theories also help to make the world more predictable. Piaget identified that knowledge and understanding moves from physical or concrete understanding of abstract thinking.

In Piaget’s view, learning proceeded by the interplay of assimilation (adjusting new experiences to fit prior concepts) and accommodation (adjusting concepts to fit new experiences). The to-and-fro of these two processes leads not only to short-term learning but also to long-term developmental change. The long-term developments are really the main focus of Piaget’s cognitive theory.

There have been minor revisions made to Piaget’s theory, for example, Baillargeon (1987) demonstrated that infants understand objects much earlier than Piaget claimed. Some of Piaget’s observations and findings could have been more about memory and not about an understanding of objects and that this understanding may occur earlier than Piaget believed. It does not mean that his theory was fundamentally wrong, just that it may need some revision.

The Piagetian version of constructivist learning is rather “individualistic,” in the sense that it does not say much about how other people involved might assist with learning. Parents and teachers are left lingering on the sidelines with few significant responsibilities for helping learners to construct knowledge. Piaget did recognize the importance of helping others in his theory, calling the process of support or assistance social transmission; however, he did not emphasize this aspect of constructivism. Piaget was more interested in what learners could figure out on their own (Salkind, 2004). Partly for this reason, his theory is often considered less about learning and more about development, which is a long-term change in a person resulting from multiple experiences. For the same reason, educators have often found Piaget’s ideas especially helpful for thinking about students’ readiness to learn.

Unlike Piaget’s rather individually oriented version of constructivism, some psychologists have focused on the interactions between a learner and more knowledgeable individuals. One early expression of this viewpoint came from the American psychologist Jerome Bruner (1960, 1966, 1996, as cited in Lally & Valentine, 2019), who became convinced that students could usually learn more than had been traditionally expected as long as they were given appropriate guidance and resources. He called such support instructional scaffolding— literally meaning a temporary framework, like one used in constructing a building, that allows a much stronger structure to be built within it. The reason for such a bold assertion was Bruner’s belief in scaffolding—his belief in the importance of providing guidance in the right way and at the right time. When scaffolding is provided, students seem more competent and “intelligent,” and they learn more.

Similar ideas were proposed by Lev Vygotsky (1978, as cited in Lally & Valentine, 2019), whose writing focused on how a learner’s thinking is influenced by relationships with others who are more capable, knowledgeable, or expert than the learner. Vygotsky proposed that when a person is learning a new skill or solving a new problem, he or she can perform better if accompanied and helped by an expert than if performing alone—though still not as well as the expert.

The social version of constructivism, however, highlights the responsibility of the expert for making learning possible. The individual must not only have knowledge and skill but also know how to arrange experiences that make it easy and safe for learners to gain knowledge and skill themselves. In addition to knowing what is to be learned, the expert (i.e., the teacher or the CYCP) also has to break the content into manageable parts, offer the parts in a sensible sequence, provide for suitable and successful practice, bring the parts back together again at the end, and somehow relate the entire experience to knowledge and skills already meaningful to the learner.

Teachers focus primarily on education, whereas CYCPs support in terms of social, emotional, and behavioural aspects that fit in between and surround the education piece and beyond.

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

Previously, you were introduced to Jean Piaget’s perspectives on human cognitive development. Piaget is the most noted theorist when it comes to children’s cognitive development. He believed that children’s cognition develops in stages.

He explained this growth in the following stages:

- Sensory Motor Stage (Birth through 2 years old)

- Preoperational Stage (2-7 years old)

- Concrete Operational Stage (7-11 years old)

- Formal Operational Stage (12 years old- adulthood)

After observing children closely, Piaget proposed that cognition developed through distinct stages from birth through the end of adolescence. By stages he meant a sequence of thinking patterns with four key features:

- They always happen in the same order.

- No stage is ever skipped.

- Each stage is a significant transformation of the stage before it.

- Each later stage incorporated the earlier stages into itself.

Stages one to three were covered in Child Development course (you can also review the theory in our week 2 content). In this course, we will focus on the final stage.

First, let’s review how we incorporate new information from the time we are children, into the teenage years.

Adaptation

When it comes to maintaining cognitive equilibrium, young people have much more of a challenge because they are constantly being confronted with new situations. All of this new information needs to be organized. The framework for organizing information is referred to as a schema, one of the mechanisms that children use to understand the world. We develop schemata through the processes of adaptation. Adaptation can occur through assimilation and accommodation.

Sometimes when we are faced with new information, we can simply fit it into our current schema; this is called assimilation. For example, a student is given a new math problem in class. They use previously learned strategies to try to solve the problem. While the problem is new, the process of solving the problem is something familiar to the student. The new problem fits into their current understanding of the math concept.

Not all new situations fit into our current framework and understanding of the world. In these cases, we may need accommodation, which is expanding the framework of knowledge to accommodate the new situation. If the student solving the math problem could not solve it because they were missing the strategies necessary to find the answer, they would first need to learn these strategies, and then they could solve the problem.

Piaget believed that when we are faced with new information that we experience a cognitive disequilibrium. In response, we are continuously trying to regain cognitive homeostasis through adaptation. Piaget also proposed that through maturation we progress through four stages of cognitive development. As Piaget believed that adolescence was the start of the fourth stage, we will focus on the cognitive developments that occur during this stage.

Formal Operational Thought

In the last of the Piagetian stages, the young adolescent becomes able to reason not only about tangible objects and events, but also about hypothetical or abstract ones. Hence, it has the name formal operational stage—the period when the individual can “operate” on “forms” or representations. This allows an individual to think and reason with a wider perspective. This stage of cognitive development, which Piaget called formal operational thought, marks a movement from an ability to think and reason from concrete visible events to an ability to think hypothetically and entertain what-if possibilities about the world. An individual can solve problems through abstract concepts and utilize hypothetical and deductive reasoning. Adolescents initially use trial and error to solve problems, but the ability to systematically solve a problem in a logical and methodical way emerges.

Formal Operational Thinking in the Classroom

School is a main contributor in guiding students towards formal operational thought. With students at this level, the teacher can pose hypothetical (or contrary-to-fact) problems: “What if the world had never discovered oil?” or “What if dinosaurs weren’t extinct?” To answer such questions, students must use hypothetical reasoning, meaning that they must manipulate ideas that vary in several ways at once, and do so entirely in their minds.

The hypothetical reasoning that concerned Piaget primarily involved scientific problems. His studies of formal operational thinking therefore often look like problems that middle or high school teachers pose in science classes. In one problem, for example, a young person is presented with a simple pendulum, onto which different amounts of weight can be hung (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958). The experimenter asks: “What determines how fast the pendulum swings: the length of the string holding it, the weight attached to it, or the distance that it is pulled to the side?” The young person is not allowed to solve this problem by trial-and-error with the materials themselves, but must reason a way to the solution mentally. To do so systematically, he or she must imagine varying each factor separately, while also imagining the other factors that are held constant. This kind of thinking requires facility at manipulating mental representations of the relevant objects and actions—precisely the skill that defines formal operations.

As you might suspect, students with an ability to think hypothetically have an advantage in many kinds of school work: by definition, they require relatively few “props” to solve problems. In this sense they can in principle be more self-directed than students who rely only on concrete operations—certainly a desirable quality in the opinion of most teachers. Note, though, that formal operational thinking is desirable but not sufficient for school success, and that it is far from being the only way that students achieve educational success. Formal thinking skills do not ensure that a student is motivated or well-behaved, for example, nor does it guarantee other desirable skills. The fourth stage in Piaget’s theory is really about a particular kind of formal thinking, the kind needed to solve scientific problems and devise scientific experiments. Since many people do not normally deal with such problems in the normal course of their lives, it should be no surprise that research finds that many people never achieve or use formal thinking fully or consistently, or that they use it only in selected areas with which they are very familiar (Case & Okomato, 1996). For teachers, the limitations of Piaget’s ideas suggest a need for additional theories about cognitive developments—ones that focus more directly on the social and interpersonal issues of childhood and adolescence.

Hypothetical and Abstract Thinking

One of the major advances of formal operational thought is the capacity to think of possibility, not just reality. Adolescents’ thinking is less bound to concrete events than that of children; they can contemplate possibilities outside the realm of what currently exists. One manifestation of the adolescent’s increased facility with thinking about possibilities is the improvement of skill in deductive reasoning (also called top-down reasoning), which leads to the development of hypothetical thinking. This provides the ability to plan ahead, see the future consequences of an action and to provide alternative explanations of events. It also makes adolescents more skilled debaters, as they can reason against a friend’s or parent’s position. Adolescents also develop a more sophisticated understanding of probability.

- Propositional thought. The appearance of more systematic, abstract thinking also allows adolescents to comprehend higher order abstract ideas, such as those inherent in puns, proverbs, metaphors, and analogies. Their increased facility permits them to appreciate the ways in which language can be used to convey multiple messages, such as satire, metaphor, and sarcasm. (Children younger than age nine often cannot comprehend sarcasm at all). This also permits the application of advanced reasoning and logical processes to social and ideological matters such as interpersonal relationships, politics, philosophy, religion, morality, friendship, faith, fairness, and honesty. This newfound ability also allows adolescents to take other’s perspectives in more complex ways, and to be able to better think through others’ points of view.

- Metacognition. Meta-cognition refers to “thinking about thinking.” This often involves monitoring one’s own cognitive activity during the thinking process. Adolescents are more aware of their own thought processes and can use mnemonic devices and other strategies to think and remember information more efficiently. Metacognition provides the ability to plan ahead, consider the future consequences of an action, and provide alternative explanations of events.

- Relativism. The capacity to consider multiple possibilities and perspectives often leads adolescents to the conclusion that nothing is absolute– everything appears to be relative. As a result, teens often start questioning everything that they had previously accepted– such as parent and family values, authority figures, religious practices, school rules, and political events. They may even start questioning things that took place when they were younger, like adoption or parental divorce. It is common for parents to feel that adolescents are just being argumentative, but this behaviour signals a normal phase of cognitive development.

Adolescent Egocentrism

Adolescents’ newfound meta-cognitive abilities also have an impact on their social cognition, as it results in increased introspection, self-consciousness, and intellectualization. Adolescents are much better able to understand that people do not have complete control over their mental activity. Being able to introspect may lead to forms of egocentrism, or self-focus, in adolescence. Adolescent egocentrism is a term that David Elkind (1967) used to describe the phenomenon of adolescents’ inability to distinguish between their perception of what others think about them and what people actually think in reality. Elkind’s theory on adolescent egocentrism is drawn from Piaget’s theory on cognitive developmental stages, which argues that formal operations enable adolescents to construct imaginary situations and abstract thinking.

Accordingly, adolescents are able to conceptualize their own thoughts and conceive of other people’s thoughts. However, Elkind pointed out that adolescents tend to focus mostly on their own perceptions, especially on their behaviours and appearance, because of the “physiological metamorphosis” they experience during this period. This leads to adolescents’ belief that other people are as attentive to their behaviours and appearance as they are themselves (Elkind, 1967; Schwartz, P. D., Maynard, A. M., & Uzelac, S. M., 2008). According to Elkind, adolescent egocentrism results in two distinct problems in thinking: the imaginary audience and the personal fable. These likely peak at age fifteen, along with self-consciousness in general.

Imaginary audience is a term that Elkind used to describe the phenomenon that an adolescent anticipates the reactions of other people to him/herself in actual or impending social situations. Elkind argued that this kind of anticipation could be explained by the adolescent’s conviction that others are as admiring or as critical of them as they are of themselves. As a result, an audience is created, as the adolescent believes that he or she will be the focus of attention. However, more often than not the audience is imaginary because in actual social situations individuals are not usually the sole focus of public attention. Elkind believed that the construction of imaginary audiences would partially account for a wide variety of typical adolescent behaviours and experiences; and imaginary audiences played a role in the self-consciousness that emerges in early adolescence. However, since the audience is usually the adolescent’s own construction, it is privy to his or her own knowledge of him/herself. According to Elkind, the notion of imaginary audience helps to explain why adolescents usually seek privacy and feel reluctant to reveal themselves–it is a reaction to the feeling that one is always on stage and constantly under the critical scrutiny of others.

Elkind also suggested that adolescents have another complex set of beliefs: They are convinced that their own feelings are unique and they are special and immortal. Personal fable is the term Elkind used to describe this notion, which is the complement of the construction of an imaginary audience. Since an adolescent usually fails to differentiate their own perceptions and those of others, they tend to believe that they are of importance to so many people (the imaginary audiences) that they come to regard their feelings as something special and unique. They may feel that they are the only ones who have experienced strong and diverse emotions, and therefore others could never understand how they feel. This uniqueness in one’s emotional experiences reinforces the adolescent’s belief of invincibility, especially to death.

This adolescent belief in personal uniqueness and invincibility becomes an illusion that they can be above some of the rules, constraints, and laws that apply to other people; even consequences such as death (called the invincibility fable). This belief that one is invincible removes any impulse to control one’s behaviour (Lin, 2016). Therefore, adolescents will engage in risky behaviours, such as drinking and driving or unprotected sex, and feel they will not suffer any negative consequences.

Intuitive and Analytic Thinking

Piaget emphasized the sequence of cognitive developments that unfold in four stages. Others suggest that thinking does not develop in sequence, but instead, that advanced logic in adolescence may be influenced by intuition. Cognitive psychologists often refer to intuitive and analytic thought as the dual-process model; the notion that humans have two distinct networks for processing information (Kuhn, 2013.)

Intuitive thought is automatic, unconscious, and fast, and it is more experiential and emotional. In contrast, analytic thought is deliberate, conscious, and rational (logical). Although these systems interact, they are distinguishable (Kuhn, 2013). Intuitive thought is easier, quicker, and more commonly used in everyday life. The discrepancy between the maturation of the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex, as discussed in the section on adolescent brain development earlier in this module, may make teens more prone to emotional intuitive thinking than adults.

As adolescents develop, they gain in logic/analytic thinking ability but may sometimes regress, with social context, education, and experiences becoming major influences. Simply put, being “smarter” as measured by an intelligence test does not advance or anchor cognition as much as having more experience, in school and in life (Klaczynski & Felmban, 2014).

Risk-taking

Because most injuries sustained by adolescents are related to risky behaviour (alcohol consumption and drug use, reckless or distracted driving, and unprotected sex), a great deal of research has been conducted to examine the cognitive and emotional processes underlying adolescent risk-taking. In addressing this issue, it is important to distinguish three facets of these questions: (1) whether adolescents are more likely to engage in risky behaviours (prevalence), (2) whether they make risk-related decisions similarly or differently than adults (cognitive processing perspective), or (3) whether they use the same processes but weigh facets differently and thus arrive at different conclusions. Behavioural decision-making theory proposes that adolescents and adults both weigh the potential rewards and consequences of an action. However, research has shown that adolescents seem to give more weight to rewards, particularly social rewards, than do adults. Adolescents value social warmth and friendship, and their hormones and brains are more attuned to those values than to a consideration of long-term consequences (Crone & Dahl, 2012).

Some have argued that there may be evolutionary benefits to an increased propensity for risk-taking in adolescence. For example, without a willingness to take risks, teenagers would not have the motivation or confidence necessary to leave their family of origin. In addition, from a population perspective, is an advantage to having a group of individuals willing to take more risks and try new methods, counterbalancing the more conservative elements typical of the received knowledge held by older adults.

Education in Adolescence

Adolescents spend more waking time in school than in any other context (Eccles & Roeser, 2011). Secondary education denotes the school years after junior or elementary school (known as primary education) and before college or university (known as post-secondary education). Adolescents who complete primary education (learning to read and write) and continue on through secondary and tertiary education tend to also have better health, wealth, and family life (Rieff, 1998). Because the average age of puberty has declined over the years, middle schools were created for grades 5 or 6 through 8 as a way to distinguish between early adolescence and late adolescence, especially because these adolescents differ biologically, cognitively and emotionally, and definitely have different needs.

Middle School

Transition to middle school is stressful and the transition is often complex. When students transition from elementary (junior) to middle school, many students are undergoing physical, intellectual, social, emotional, and moral changes as well (Parker, 2013). Research suggests that early adolescence is an especially sensitive developmental period (McGill, Hughes, Alicea, & Way, 2012). Some students mature faster than others. Students who are developmentally behind typically experience more stress than their counterparts (U.S. Department of Education, 2008). Consequently, they may earn lower grades and display decreased academic motivation, which may increase the rate of dropping out of school (U.S. Department of Education, 2008). For many middle school students, academic achievement slows down and behavioural problems can increase.

Regardless of a student’s gender or ethnicity, middle school can be challenging. Although young adolescents seem to desire independence, they also need protection, security, and structure (Brighton, 2007). Baly, Cornell, and Lovegrove (2014) found that bullying increases in middle school, particularly in the first year. Just when egocentrism is at its height, students are worried about being thrown into an environment of independence and responsibility. Additionally, unlike elementary school, concerns arise regarding structural changes– students typically go from having one primary teacher in elementary school to multiple different teachers during middle school. They are expected to get to and from classes on their own, manage time wisely, organize and keep up with materials for multiple classes, be responsible for all classwork and homework from multiple teachers, and at the same time develop and maintain a social life (Meece & Eccles, 2010). Students are trying to build new friendships and maintain ones they already have. As noted throughout this module, peer acceptance is particularly important. Another aspect to consider is technology. Typically, adolescents get their first cell phone at about age 11 and, simultaneously, they are also expected to research items on the Internet. Social media use and texting increase dramatically and the research finds both costs and benefits to this use (Coyne, Padilla-Walker & Holmgren, 2018).

Stage-environment Fit. A useful perspective that explains much of the difficulty faced by early adolescents in middle school, and the declines found in classroom engagement and academic achievement, is stage-environment fit theory (Eccles, Midgley, Wigfield, Buchanan, Reuman, Flanagan, & MacIver, 1993). This theory highlights the developmental mismatch between the needs of adolescents and the characteristics of the middle school context. At the same time that teens are developing greater needs for cognitive challenges, autonomy, independence, and stronger relationships outside the family, schools are becoming more rigid, controlling, and unstimulating. The middle school environment is experienced as less supportive than elementary school, with multiple teachers and less closeness and warmth in teacher-student relationships. Disciplinary concerns can make classrooms more controlling, while standardized testing and organizational constraints make curriculum more uniform, and less challenging and interesting. Existing relationships with peers are often disrupted and students find themselves in a larger and more complex social context. This poor fit between the needs of students at certain stages and their school contexts is more pronounced over school transitions, but continues all throughout secondary education.

High School

As adolescents enter into high school, their continued cognitive development allows them to think abstractly, analytically, hypothetically, and logically, which is all formal operational thought. High school emphasizes formal thinking in attempt to prepare graduates for college where analysis is required. Overall, high school graduation rates in the United States have increased steadily over the past decade, reaching 83.2 percent in 2016 after four years in high school (Gewertz, 2017). Additionally, many students in the United States do attend college. Unfortunately, though, about half of those who go to college leave without completing a degree (Kena et al., 2016). Those that do earn a degree, however, do make more money and have an easier time finding employment. The key here is understanding adolescent development and supporting teens in making decisions about college or alternatives to college after high school.

Academic achievement during adolescence is predicted by factors that are interpersonal (e.g., parental engagement in adolescents’ education), intrapersonal (e.g., intrinsic motivation), and institutional (e.g., school quality). Academic achievement is important in its own right as a marker of positive adjustment during adolescence but also because academic achievement sets the stage for future educational and occupational opportunities. The most serious consequence of school failure, particularly dropping out of school, is the high risk of unemployment or underemployment in adulthood that follows. High achievement can set the stage for college or future vocational training and opportunities.

We’ll explore more of this topic another week!

Link to Learning

What do you think, is college necessary? Is it worth the investment? Read the article “Is College Necessary?” from Psychology Today (https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/teen-angst/201804/is-college-necessary) geared towards parents who can help their teenager decide if college is right for them.

Moral Reasoning During Adolescence

As adolescents become increasingly independent, they also develop more nuanced thinking about morality, or what is right or wrong. We all make moral judgments on a daily basis. As adolescents’ cognitive, emotional, and social development continue to mature, their understanding of morality expands and their behaviour becomes more closely aligned with their values and beliefs. Therefore, moral development describes the evolution of these guiding principles and is demonstrated by the ability to apply these guidelines in daily life. Understanding moral development is important in this stage where individuals make so many important decisions and gain more and more legal responsibility.

Influences on moral reasoning

Adolescents are receptive to their culture, to the models they see at home, in school, and in the mass media. These observations influence moral reasoning and moral behaviour. When children are younger, their family, culture, and religion greatly influence their moral decision-making. During the early adolescent period, peers have a much greater influence. Peer pressure can exert a powerful influence because friends play a more significant role in teens’ lives.

Furthermore, the new ability to think abstractly enables youth to recognize that rules are simply created by other people. As a result, teens begin to question the absolute authority of parents, schools, government, and other traditional institutions (Vera-Estay, Dooley, & Beauchamp, 2014). By late adolescence, most teens are less rebellious as they have begun to establish their own identity, their own belief system, and their place in the world.

Unfortunately, some adolescents have life experiences that may interfere with their moral development. Traumatic experiences may cause them to view the world as unjust and unfair. Additionally, social learning also impacts moral development. Adolescents may have observed the adults in their lives, making immoral decisions that disregarded the rights and welfare of others, leading these youth to develop beliefs and values that are contrary to the rest of society. That being said, adults have opportunities to support moral development by modeling the moral character that we want to see in our children. Parents are particularly important because they are generally the original source of moral guidance. Authoritative parenting facilitates children’s moral growth better than other parenting styles, and one of the most influential things a parent can do is to encourage the right kind of peer relations (McDevitt & Ormrod, 2004). While parents may find this process of moral development difficult or challenging, it is important to remember that this developmental step is essential to their children’s well-being and ultimate success in life.

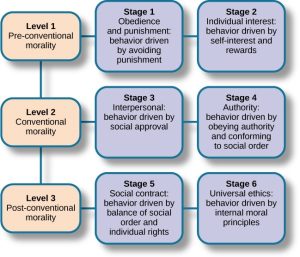

If you recall from when you learned about development in Middle Childhood, Lawrence Kohlberg (1984, as cited in Lally & Valentine, 2019) argued that moral development moves through a series of stages, and reasoning about morality becomes increasingly complex (somewhat in line with increasing cognitive skills, as per Piaget’s stages of cognitive development). As children develop intellectually, they pass through three stages of moral thinking: the preconventional level, the conventional level, and the postconventional level. In middle childhood into early adolescence, the child begins to care about how situational outcomes impact others and wants to please and be accepted (conventional morality). At this developmental phase, people are able to value the good that can be derived from holding to social norms in the form of laws or less formalized rules. From adolescence and beyond, adolescents begin to employ abstract reasoning to justify behaviours. Moral behaviour is based on self-chosen ethical principles that are generally comprehensive and universal, such as justice, dignity, and equality, which is postconventional morality.

Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development

Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg (1927–1987) extended upon the foundation that Piaget built regarding moral and cognitive development. Kohlberg, like Piaget, was interested in moral reasoning. Moral reasoning does not necessarily equate to moral behaviour. Holding a particular belief does not mean that our behaviour will always be consistent with the belief. To develop this theory, Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas to people of all ages, and then he analyzed their answers to find evidence of their particular stage of moral development. After presenting people with this and various dilemmas, Kohlberg reviewed people’s responses and placed them in different stages of moral reasoning. According to Kohlberg, an individual progresses from the capacity for pre-conventional morality (before age 9) to the capacity for conventional morality (early adolescence), and toward attaining post-conventional morality (once formal operational thought is attained), which only a few fully achieve.

Moral Stages According to Kohlberg

Using a stage model similar to Piaget’s, Kohlberg proposed three levels, with six stages, of moral development. Individuals experience the stages universally and in sequence as they form beliefs about justice. He named the levels simply preconventional, conventional, and postconventional.

Preconventional: Obedience and Mutual Advantage

The preconventional level of moral development coincides approximately with the preschool period of life and with Piaget’s preoperational period of thinking. At this age, the child is still relatively self-centered and insensitive to the moral effects of actions on others. The result is a somewhat short-sighted orientation to morality. Initially (Kohlberg’s Stage 1), the child adopts an ethics of obedience and punishment —a sort of “morality of keeping out of trouble.” The rightness and wrongness of actions are determined by whether actions are rewarded or punished by authorities, such as parents or teachers. If helping yourself to a cookie brings affectionate smiles from adults, then taking the cookie is considered morally “good.” If it brings scolding instead, then it is morally “bad.” The child does not think about why an action might be praised or scolded; in fact, says Kohlberg, he would be incapable, at Stage 1, of considering the reasons even if adults offered them.

Eventually, the child learns not only to respond to positive consequences but also learns how to produce them by exchanging favors with others. The new ability creates Stage 2, ethics of market exchange. At this stage, the morally “good” action is one that favors not only the child but another person directly involved. A “bad” action is one that lacks this reciprocity. If trading the sandwich from your lunch for the cookies in your friend’s lunch is mutually agreeable, then the trade is morally good; otherwise, it is not. This perspective introduces a type of fairness into the child’s thinking for the first time. However, it still ignores the larger context of actions—the effects on people not present or directly involved. In Stage 2, for example, it would also be considered morally “good” to pay a classmate to do another student’s homework—or even to avoid bullying—provided that both parties regard the arrangement as being fair.

Conventional: Conformity to Peers and Society

As children move into the school years, their lives expand to include a larger number and range of peers and (eventually) of the community as a whole. The change leads to conventional morality, which are beliefs based on what this larger array of people agree on—hence Kohlberg’s use of the term “conventional.” At first, in Stage 3, the child’s reference group are immediate peers, so Stage 3 is sometimes called the ethics of peer opinion. If peers believe, for example, that it is morally good to behave politely with as many people as possible, then the child is likely to agree with the group and to regard politeness as not merely an arbitrary social convention, but a moral “good.” This approach to moral belief is a bit more stable than the approach in Stage 2 because the child is taking into account the reactions not just of one other person, but of many. But it can still lead astray if the group settles on beliefs that adults consider morally wrong, like “Shoplifting for candy bars is fun and desirable.”

Eventually, as the child becomes a youth and the social world expands, even more, he or she acquires even larger numbers of peers and friends. He or she is, therefore, more likely to encounter disagreements about ethical issues and beliefs. Resolving the complexities lead to Stage 4, the ethics of law and order, in which the young person increasingly frames moral beliefs in terms of what the majority of society believes. Now, an action is morally good if it is legal or at least customarily approved by most people, including people whom the youth does not know personally. This attitude leads to an even more stable set of principles than in the previous stage, though it is still not immune from ethical mistakes. A community or society may agree, for example, that people of a certain race should be treated with deliberate disrespect, or that a factory owner is entitled to dump wastewater into a commonly shared lake or river. To develop ethical principles that reliably avoid mistakes like these require further stages of moral development.

Postconventional: Social Contract and Universal Principles

As a person becomes able to think abstractly (or “formally,” in Piaget’s sense), ethical beliefs shift from acceptance of what the community does believe to the process by which community beliefs are formed. The new focus constitutes Stage 5, the ethics of social contract. Now an action, belief, or practice is morally good if it has been created through fair, democratic processes that respect the rights of the people affected. Consider, for example, the laws in some areas that require motorcyclists to wear helmets. In what sense are the laws about this behaviour ethical? Was it created by consulting with and gaining the consent of the relevant people? Were cyclists consulted, and did they give consent? Or how about doctors or the cyclists’ families? Reasonable, thoughtful individuals disagree about how thoroughly and fairly these consultation processes should be. In focusing on the processes by which the law was created; however, individuals are thinking according to Stage 5, the ethics of social contract, regardless of the position they take about wearing helmets. In this sense, beliefs on both sides of a debate about an issue can sometimes be morally sound, even if they contradict each other.

Paying attention to due process certainly seems like it should help to avoid mindless conformity to conventional moral beliefs. As an ethical strategy, though, it too can sometimes fail. The problem is that an ethics of social contract places more faith in the democratic process than the process sometimes deserves, and does not pay enough attention to the content of what gets decided. In principle (and occasionally in practice), a society could decide democratically to kill off every member of a racial minority, but would deciding this by due process make it ethical? The realization that ethical means can sometimes serve unethical ends leads some individuals toward Stage 6, the ethics of self-chosen, universal principles. At this final stage, the morally good action is based on personally held principles that apply both to the person’s immediate life as well as to the larger community and society. The universal principles may include a belief in democratic due process (Stage 5 ethics), but also other principles, such as a belief in the dignity of all human life or the sacredness of the natural environment. At Stage 6, the universal principles will guide a person’s beliefs even if the principles mean occasionally disagreeing with what is customary (Stage 4) or even with what is legal (Stage 5).

Influences on Moral Development

Adolescents are receptive to their culture, to the models they see at home, in school and in the mass media. These observations influence moral reasoning and moral behaviour. When children are younger, their family, culture, and religion greatly influence their moral decision-making. During the early adolescent period, peers have a much greater influence. Peer pressure can exert a powerful influence because friends play a more significant role in teens’ lives. Furthermore, the new ability to think abstractly enables youth to recognize that rules are simply created by other people. As a result, teens begin to question the absolute authority of parents, schools, government, and other traditional institutions (Vera-Estay, Dooley, & Beauchamp, 2014). By late adolescence, most teens are less rebellious as they have begun to establish their own identity, their own belief system, and their own place in the world.

Unfortunately, some adolescents have life experiences that may interfere with their moral development. Traumatic experiences may cause them to view the world as unjust and unfair. Additionally, social learning also impacts moral development. Adolescents may have observed the adults in their lives making immoral decisions that disregarded the rights and welfare of others, leading these youth to develop beliefs and values that are contrary to the rest of society. That being said, adults have opportunities to support moral development by modeling the moral character that we want to see in our children. Parents are particularly important because they are generally the original source of moral guidance. Authoritative parenting facilitates children’s moral growth better than other parenting styles and one of the most influential things a parent can do is to encourage the right kind of peer relations. While parents may find this process of moral development difficult or challenging, it is important to remember that this developmental step is essential to their children’s well-being and ultimate success in life.

Link to Learning

Parenting has the largest impact on adolescent moral development. Read more here in this article, “Building Character: Moral Development in Adolescence” (https://parentandteen.com/building-character-moral-development-in-adolescence/) from the Center for Parent and Teen Communication (2018).

We can go into a lot of detail on moral development, but this is a good start for now. We’ll pick up on this topic and look at the influences on moral development in more detail in another class.

References

Baly, M.W., Cornell, D.G., & Lovegrove, P. (2014). A longitudinal investigation of self and peer reports of bullying victimization across middle school. Psychology in the Schools, 51(3), 217-240.

Brighton, K. L. (2007). Coming of age: The education and development of young adolescents. Westerville, OH: National Middle School Association.

Center for Parent and Teen Communication (2018). Building Character: Moral Development in Adolescence. https://parentandteen.com/building-character-moral-development-in-adolescence/

Coyne, S.M., Padilla-Walker, L.M., & Holmgren, H.G. (2018). A six-year longitudinal study of texting trajectories duringadolescence. Child Development, 89(1), 58-65.

Crone, E.A., & Dahl, R.E. (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(9), 636-650.

Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & MacIver, D. (1993). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 48(2), 90–101.

Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225-241.

Elkind, D. (1967). Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Development, 38, 1025-1034.

Gewertz, C. (2017, May 3). Is the high school graduation rate inflated? No, study says (Web log post). Education Week.

Inhelder, B. & Piaget, J. (1958). The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence. NY: Basic Books.

Kena, G., Hussar, W., McFarland, J., de Brey, C., Musu-Gillette, L., Wang, X., & Dunlop Velez, E. (2016). The condition of education 2016. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Klaczynski, P. (2001). Analytic and heuristic processing influences on adolescent reasoning and decision-making. Child Development, 72 (3), 844-861.

Klaczynski, P.A. & Felmban, W.S. (2014). Heuristics and biases during adolescence: Developmental reversals and individual differences. In Henry Markovitz (Ed.), The developmental psychology of reasoning and decision making, pp. 84-111. NY: Psychology Press.

Kuhn, D. (2013). Reasoning. In. P.D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology. (Vol. 1, pp. 744-764). New York NY: Oxford University Press.

McDevitt, T.M. & Ormrod, J.E. (2004). Child development: Educating and working with children and adolescents. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

McGill, R.K., Hughes, D., Alicea, S., & Way, N. (2012). Academic adjustment across middle school: The role of public regard and parenting. Developmental Psychology, 48(4), 1003-1008.

Meece, J.L. & Eccles, J.S. (Eds.). (2010). Handbook on research on schools, schooling, and human development. New York, NY: Routledge.

Rieff, M.I. (1998). Adolescent school failure: Failure to thrive in adolescence. Pediatrics in Review, 19(6).

Salkind, N. (2004). An introduction to theories of human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Schwartz, P. D., Maynard, A. M., & Uzelac, S. M. (2008). Adolescent egocentrism: A contemporary view. Adolescence, 43, 441-447.

Vera-Estay, E. Dooley, J.J., & Beauchamp, M.H. (2014). Cognitive underpinnings of moral reasoning in adolescence: The contribution of executive functions. Journal of Moral Education, 44 (1), 17-33.

OER Attributions:

“Educational Psychology” by Kevin Seifert is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0 International License.

“Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0/modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Dan Grimes, Portland State University

Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License/modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Dan Grimes, Portland State University

Additional written materials by Dan Grimes & Brandy Brennan, Portland State University and are licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0