Adolescent Health

Learning Objectives

1. Classify essential elements of adolescent physical health.

2. Research culturally specific developmental norms during adolescence.

Adolescent Health

In the last few weeks we have learned about the physical changes that take place during adolescence, with the beginnings of puberty and the physical growth that takes place both within the body and within the brain itself. We have also learned about sexual health, sexual activity, and gender identity and expression. We explored the relevance of this information to our work as Child and Youth Care Practitioners (CYCPs).

Research about adolescents (and development in general) is typically culturally specific, and much of the research centers around western and Eurocentric norms. For example, G. Stanley Hall is seen as one of the first researchers to study adolescents as a separate age group (Chen & Farruggia, 2002). He described adolescence as a time of “storm and stress” caused by “raging hormones” (Hall, 1904 as cited in Chen & Farruggia, 2002) as a result of entering puberty. Those are some emotionally charged words. This was back in 1904. Read that again: Over 100 years ago! The authors also indicate that “up until the 1950s, less than 5% of research on adolescence included cultural or cross-cultural elements. The proportion increased to 7% between the 1960s and 1980s. The past two decades, however, have witnessed a major surge: Cultural and cross-cultural research accounts for 14% of recent adolescent research.” (Chen & Farruggia, 2002 p. 3). Given how culturally diverse the GTA and Canada have become, many of these norms may not be as relevant to today’s Canadian teens.

There are several factors that determine healthy physical growth for adolescents. The World Health Organization (WHO) lists several primary health issues for adolescents and emerging (young) adults (WHO, 2022) such as physical activity, nutrition, injuries and violence, mental health substance use, infections and diseases including HIV/AIDS and other STIs, early pregnancy and childbirth for girls. We could have an entire course focused on these topics alone! Sadly, we cannot. Therefore, for the purpose of our work as CYCPs, we will focus on the following elements of adolescent health:

- Culture

- Social Determinants of Health

- Nutrition

- Physical activity

- Sleep

Culture

Understanding culture is a big piece to understanding how developmental theories and milestones can be relevant (or not relevant) to young people. There are many different definitions of culture, the sum of which can be defined as “the shared patterns of behaviours and interactions, cognitive constructs, and affective understanding that are learned through a process of socialization” (Centre for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition, 2023 as cited in Caring for Kids New to Canada, 2018a). Culture is ever-evolving, and can include culture of origin as well as incorporating elements of a new culture, for example for young people who are newcomers to a country (Caring for Kids New to Canada, 2018a). Even within cultures, there are variations and great diversity (Caring for Kids New to Canada, 2018b); the term “cultural competence” is used a lot, however it is important to know that while we can be aware of many different cultures, we can never truly be experts. The experts in their own experience are the young people and families we work with!

Culture can be influenced by many factors, and include any and/or all of the following: age, language, ethnicity, life experience, socio-economic status, gender, sexual orientation, education, upbringing, religion and spiritual beliefs, geography (Caring for Kids New to Canada, 2018a).

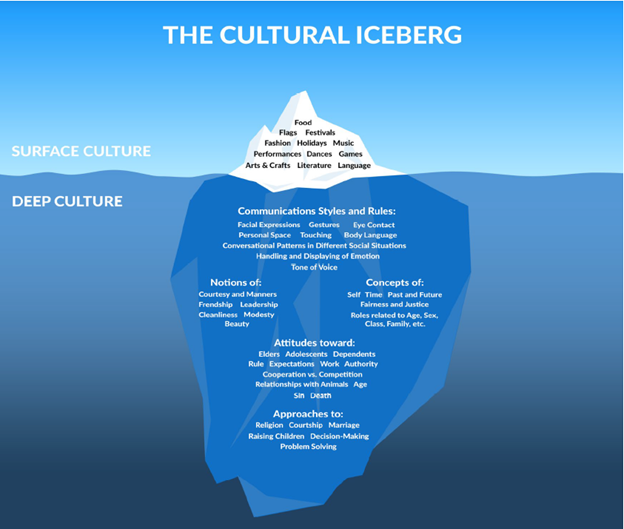

There are many elements to culture, some more visible than others. See this image that depicts an iceberg model of culture:

“Culture, religion and ethnicity may influence beliefs and values that people have about health and health care” (Caring for Kids New to Canada, 2018a, p. 1) which is helpful for us as CYCPs to be aware of. Our own health care system in Ontario, and in Canada “has been shaped by the mainstream beliefs of historically dominant cultures” (Caring for Kids New to Canada, 2018a, p. 1). What may be an area of interest or concern in one country, may not be as prevalent in another. As mentioned earlier, this means that these mainstream beliefs can be outdated, or not entirely relevant or accurate to someone. Culture can also influence how an individual views health, illness, how easily one has access to health care providers, and lead to stigmas that can impact seeking and receiving supports.

To work effectively with individuals who identify with a culture different than our own, the Child and Youth Care Competencies state: “The Professional Practitioner seeks self understanding and has the ability to access and evaluate information related to cultural and human diversity” (CYCCB, 2010, p. 12). The second competency is Cultural and Human Diversity, which offers more information on how to achieve this as a CYCP. Asking questions and opening the conversation to be curious about (and not assume) a young person’s views on health can support us to determine the relevance and identify exceptionalities to the developmental milestones we are exploring. Review your notes from your Foundations in Child and Youth Care course for a refresher on the competency.

Social Determinants of Health

Authors Raphael, Bryant, Mikkonen and Raphael (2020) outline the factors that shape “the health of Canadians” (Raphael et al., 2020 p. 11) that go beyond just lifestyle and medical treatments available, and the effects of these are “stronger than the ones associated with behaviours such as diet, physical activity, and even tobacco and excessive alcohol use” (Raphael et al., 2020 p. 14).

The social determinants of health are:

- disability

- early child development

- education

- employment, job security, working conditions

- food insecurity

- gender

- geography

- globalization

- health services

- housing

- immigration

- income and income distribution

- Indigenous ancestry

- race

- social exclusion

- social safety net

We could also (unofficially) add literacy, access to information, and media literacy as other sub-factors.

An individual who experiences stress, barriers, or discrimination based on one or more of these social determinants of health may experience chronic stress, and “prolonged biological reactions that strain the physical body” (Raphael et al., 2020 p. 15). Imagine working with a young person who is experiencing social exclusion, limited access to resources or health services, and has a disability. Or imagine a young person living in rural Ontario who is Indigenous, and their town has no running water and limited access to food. Would their physical development meet the milestones set out by theorists and researchers from 100 years ago? Probably not. All of these elements, in addition to things such as genetics, biology, and culture, can all lead to various outcomes.

The relevance for CYCPs is that if we are working with someone who is not meeting a developmental milestone, there may be more to it than that. Developing interventions that address the milestone, for example, providing activities that promote physical activity, only begin to address lack of physical activity. They do necessarily go deeper to address the underlying cause. Providing access to resources, advocating for services and programs that meet more than one need can also support meeting (and maintaining) this developmental milestone. While we are not health professionals, we can support development. The more we understand about a young person, the more we’re able to support, and work alongside other professionals.

Again, we could have an entire course on the social determinants of health. To read more, check out: https://thecanadianfacts.org/ and read the full report.

Nutrition

Adequate adolescent nutrition is necessary for optimal growth and development. Dietary choices and habits established during adolescence greatly influence future health (Canada’s Food Guide, 2023) yet many studies report that teens consume few fruits and vegetables and are not receiving the calcium, iron, vitamins, or minerals necessary for healthy development. Access to healthy food is another concern, which can impact nutrition -one of the social determinants of health listed above (Raphael et al., 2020).

Healthy eating, according to Canada’s Food Guide, includes food choices, having and maintaining healthy eating habits, and learning skills such as how to plan for, buy or access, and prepare healthy foods (2022). Many resources are available to support talking to adolescents about healthy eating. Check out unlockfood.ca (2023) a website created by the Dietitians of Canada: Teenagers: Articles.

One of the reasons for poor nutrition may also be anxiety about body image, which is a person’s idea of how they feel about or view their body. The way adolescents feel about their bodies can affect the way they feel about themselves as a whole. Young people often feel dissatisfied with their body weight and size (Abbott, Lee, Stubbs & Davies, 2010; Duncan, Duncan & Schofield, 2011 as Cited in Freeman, King, Pickett, Craig, Elgar, Janssen & Klinger, 2011). Few adolescents welcome their sudden weight increase, so they may adjust their eating habits to lose weight. Adding to the rapid physical changes, they are simultaneously bombarded by messages, and sometimes teasing, related to body image, appearance, attractiveness, weight, and eating that they encounter in the media, at home, and from their friends/peers (both in-person and via social media).

Much research has been conducted on the psychological ramifications of body image on adolescents. Modern-day teenagers are exposed to more media on a daily basis than any generation before them.

A recent study has indicated that the average Canadian teenager accesses social media an average of one to two hours a day during the week, and three or more hours on weekends (MediaSmarts, 2022). As such, adolescents are exposed to many representations of ideal, societal beauty. The concept of a person being unhappy with their own image or appearance has been defined as “body dissatisfaction.” In teenagers, body dissatisfaction is often associated with body mass, low self-esteem, and atypical eating patterns. Scholars continue to debate the effects of media on body dissatisfaction in teens. In a 2011 study of Canadian adolescents, the percentage of teens who reported actively trying to lose weight decreased from 20% of girls (assigned at birth) and 10% of boys (assigned at birth) in 2006 to 16% of girls and 9% of boys in 2010 (Freeman et al., 2011).

Obesity

One concern for health professionals working with adolescents is the current rate of obesity. Freeman and colleagues (2011) state that “excess weight and obesity among young people are leading public health issues in Canada” (p. 136). In 2017, Health Canada published reports indicating that 30% of children and teens ages five to seventeen years were overweight or obese (Health Canada, 2017).

The terms “overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health” (WHO, 2021, p. 1). The Body Mass Index (BMI) is an “index of weight-for-height that is commonly used to classify overweight and obesity in adults. It is defined as a person’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of his height in meters (kg/m2)” (WHO, 2021, p. 1).

Earlier it was mentioned that culture, based on mainstream beliefs, may influence how health is viewed and assessed. One example of this is the Body Mass Index (BMI) tool (Nordqvist, 2022) which many critics say is outdated and inaccurate. You can read this article if you’re interested in learning more: Why BMI is inaccurate and misleading. Having said all that, it is still the primary tool used by health care professionals.

Causes and consequences of Obesity

According to the WHO (2021) and Health Canada (2006) obesity originates from a complex set of contributing factors, including one’s environment, behaviour, and genetics. Societal factors include culture, education, food marketing and promotion, the quality of food, and the physical activity environment available. Behaviours leading to obesity include diet, the amount of physical activity, and medication use.

There are many health consequences to obesity, including asthma, Type 2 Diabetes, cardiovascular diseases (e.g., high blood pressure and heart disease.

Eating Disorders and disordered eating

Dissatisfaction with body image, bullying, and the influence of social media can explain why many teens, mostly girls, eat erratically or ingest diet pills to lose weight and why boys may take steroids to increase their muscle mass. Although eating disorders can occur in children and adults, they frequently appear during the teen years or young adulthood (NEDIC, n.d.). Eating disorders affect both genders, although rates among women are greater than among men. “Findings from the last Canadian Community Health Survey – Mental Health indicate that in 2012, over 113 000 individuals ages 15 and older were living with an eating disorder diagnosed by a health professional” (Statistics Canada, n.d. as cited in NEDIC, 2021, p. 1).

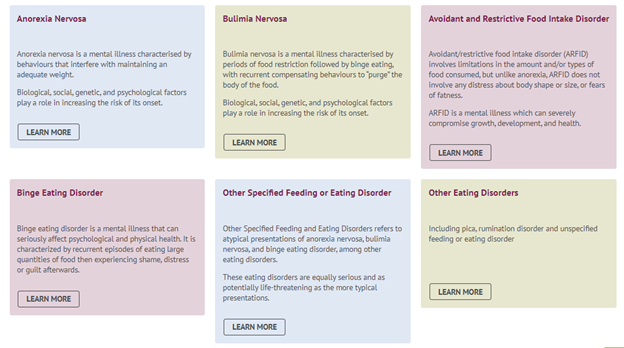

The main criteria for the most common eating disorders: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder are described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition, DSM-5 (NEDIC, 2021).

You will learn more about eating disorders in your Mental Health course in second year.

Physical Activity

Middle childhood and adolescence seem to be a great time to introduce children to organized sports, and in fact, many parents do. Nearly 84% of Canadian children and teens ages 3-17 “are participating in some type of sport and 60 percent are doing it on an organized basis” (Solutions Research Group, 2014).

The most important supports for young people with regard to physical activity, sleep, and sedentary behaviours are: families, communities, schools, child care, health care, and systemic elements such as government initiatives “by encouraging, facilitating, modelling, setting expectations and engaging in healthy movement behaviours with them” (ParticipAction, 2020).

This is an excellent example of how we can view systems, or the environment (remember Ecological Systems Theory?) in how they interact with and influence young people.

Physical activity supports and builds social skills, improves athletic ability, and teaches a sense of competition. However, it has been suggested that the emphasis on competition and athletic abilities can be counterproductive and lead children to grow tired of the game and want to quit. Sports are important for children. Children’s participation in sports has been linked to:

- Higher levels of satisfaction with family and overall quality of life for young people

- Improved physical and emotional development

- Better academic performance

(KidSportCanada, 2022; Government of Canada, 2022).

Yet, a new Canadian initiative has found that gender, poverty, location, ethnicity, and disability can limit opportunities to engage in sports (KidSportCanada, 2022; Government of Canada, 2022).

Physical Education

For many children, physical education in school is a key component in introducing children to sports. After years of schools cutting back on physical education programs, there has been a turnaround, prompted by concerns over childhood obesity and related health issues. ParticipAction’s 24-hour movement guidelines (2020) recommend 60 minutes per day of moderate to vigorous physical activity for young people ages five to seventeen years.

Sleep

Brain development even affects the way teens sleep. Adolescents’ normal sleep patterns are different from those of children and adults. Teens are often drowsy upon waking, tired during the day, and wakeful at night. Although it may seem like teens are lazy, science shows that melatonin levels (or the “sleep hormone” levels) in the blood naturally rise later at night and fall later in the morning in teens than in most children and adults. This may explain why many teens stay up late and struggle with getting up in the morning.

According to Canada’s 24-Hour movement guidelines, young people ages 5-13 years should have between 9 to 11 hours of uninterrupted sleep each night. For teens ages 14-17 years, the recommendations are 8 to 10 hours per night with consistent bed and wake-up times (ParticipAction, 2016).

Link to Learning: School Start Times

As research reveals the importance of sleep for teenagers, many people advocate for later high school start times. Read about some of the research in the US at the National Sleep Foundation on school start times or watch this TED talk by Wendy Troxel: “Why Schools Should Start Later for Teens”

Some Toronto high schools in the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) have implemented late start dates to address these needs. However, in the past, these have been impacted by other factors (Rushowy, 2016).

Why don’t adolescents get adequate sleep? In addition to known environmental and social factors, including work, homework, media, technology, and socializing, the adolescent brain is also a factor. As adolescents go through puberty, their circadian rhythms change and push back their sleep time until later in the evening (Weintraub, 2016). This biological change not only keeps adolescents awake at night, but it also makes it difficult for them to get up in the morning. When they are awake too early, their brains do not function optimally. Impairments are noted in attention, behavior, and academic achievement, while increases in tardiness and absenteeism are also demonstrated.

The Government of Canada (2018) explored good sleep as part of a healthy lifestyle. They found that:

- 17.2% of young people that get insufficient sleep report hyperactivity compared to 11.9% of young people who get adequate sleep.

- 21.5% of young people that get insufficient sleep report stress compared to 10.3% of young people who get adequate sleep.

- 11.2% of young people that get insufficient sleep report poor mental health compared to 4.5% of young people who get adequate sleep.

Psychologists and other professionals have been advocating for later school times, and they have produced research demonstrating better student outcomes for later start times. More middle and high schools have changed their start times to reflect the sleep research better. However, the logistics of changing start times and bus schedules are proving too difficult for some schools leaving many adolescents vulnerable to the negative consequences of sleep deprivation.

Links to Learning

As research reveals the importance of sleep for teenagers, many people advocate for later high school start times. Read about some of the research at the National Sleep Foundation on school start times.

Video 5.4.1. Why Schools Should Start Later for Teens discusses how early school start times impact teens and how later start times can benefit students.

In summary

As CYPs, we will encounter young people who are not getting enough sleep or physical activity, not having access to nutritious foods, among experiencing a number of other health concerns and barriers that can impact their physical development. Having an understanding of these issues and influences on development can support our work and know how to best support healthy development.

References

Canada’s Food Guide (2022). Healthy eating for teens. https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/tips-for-healthy-eating/teens/

Caring for Kids New to Canada. (2018a). How culture influences health. https://kidsnewtocanada.ca/culture/influence

Caring for Kids New to Canada. (2018b). Cultural competence for child and youth health professionals. https://kidsnewtocanada.ca/culture/competence/

Chen, C. S., & Farruggia, S. (2002). Culture and Adolescent Development. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 6 (1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1113

CYCCB. (2010). Competencies for Professional Child & Youth Work Practitioners. https://www.cyccb.org/images/pdfs/2010_Competencies_for_Professional_CYW_Practitioners.pdf

Freeman, J. G., King, M., Pickett, W., Craig, W., Elgar, F., Janssen, I., & Klinger, D. (2011). The health of Canada’s young people: A mental health focus. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada.

Government of Canada. (2022). Minister St-Onge announces the first two national recipients of the Community Sport for All Initiative. https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/news/2022/06/minister-st-onge-announces-the-first-two-national-recipients-of-the-community-sport-for-all-initiative.html

Government of Canada. (2018). Are Canadian children getting enough sleep? https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-children-getting-enough-sleep-infographic.html

Health Canada. (2017). Tackling obesity in Canada: Childhood obesity and excess weight rates in Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/obesity-excess-weight-rates-canadian-children.html

KidSportCanada. (2022). Our Impact. https://kidsportcanada.ca/our-impact/

MediaSmarts. (2022). Young Canadians in a wireless world, Phase IV: Life online. MediaSmarts. Ottawa.

NEDIC (2021). General Information. https://nedic.ca/general-information/

Nordqvist, C. (2022). Why BMI is inaccurate and misleading. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/265215

ParticipAction. (2020). 2020 children and youth report card. https://www.participaction.com/the-science/2020-child-and-youth-report-card/

ParticipAction. (2016). 24-hour movement guidelines. https://www.participaction.com/the-science/benefits-and-guidelines/children-and-youth-age-5-to-17/

Raphael, D., Bryant, T., Mikkonen, J. and Raphael, A. (2020). Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts. Oshawa: Ontario Tech University Faculty of Health Sciences and Toronto: York University School of Health Policy and Management.

Solutions Research Group. (2014). Active healthy kids report card. http://www.activehealthykids.ca/ReportCard/2014ReportCard.aspx

Unlockfood.ca (2023). Teenagers. https://www.unlockfood.ca/en/Articles/Teenagers/

Weintraub, K. (2016). Young and sleep deprived: Psychologists’ research supports later school start times for teens’ mental health. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2016/02/sleep-deprived

World Health Organization. (2022). Adolescent and young adult health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescents-health-risks-and-solutions

World Health Organization. (2021). Obesity and overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight