Puberty and Sexuality

Learning Objectives

- Explain the various changes that take place during puberty.

- Create a strength based approach to teaching about STI’s and contraceptives.

- Discuss the difference between sexuality, gender identity and expression.

Puberty and Sexuality

When working with adolescents, Child and Youth Care Practitioners (CYCPs) require an understanding, as well as feeling comfortable discussing topics such as puberty and sexuality. If you’re interested in the science and genetics behind puberty and sexuality, there is a wealth of information available online. In this week’s reading we’ll cover the major topics and relevant areas of physical development, read on!

Physical Changes in Puberty

Puberty is the period of rapid growth and sexual development that typically begins between ages 8 and 14. While the sequence of physical changes in puberty is predictable, the onset and pace of puberty vary widely. Every person’s individual timetable for puberty is different and is primarily influenced by heredity; however environmental factors—such as diet and exercise—also exert some influence.

Adolescence has evolved historically, with evidence indicating that this stage is lengthening as individuals start puberty earlier and transition to adulthood later than in the past. Puberty today begins, on average, at age 10–11 years for girls and 11–12 years for boys. This average age of onset has decreased gradually over time since the 19th century by 3–4 months per decade, which has been attributed to a range of factors including better nutrition, obesity, increased father absence, and other environmental factors (Steinberg, 2013).

Completion of formal education, financial independence from parents, marriage, and parenthood have all been markers of the end of adolescence and beginning of adulthood, and all of these transitions happen, on average, later now than in the past.

As a result of the prolonging of adolescence, this has prompted the introduction of a new developmental period called emerging adulthood that captures these developmental changes out of adolescence and into adulthood, occurring from approximately ages 18 to 29 (Arnett, 2000). We’ll learn more about this phase later in the semester.

Let’s review what changes take place during puberty. As mentioned in the reading on physical development, keep in mind that most literature and research surrounding human growth and development, for the most part, describes development in terms of sex assigned at birth, which is “the assignment and classification of people as male, female, intersex, or another sex assigned at birth often based on physical anatomy at birth” (Trans Student Educational Resources, n.d.) which includes both biological and physical features “such as chromosomes, genitals and hormones” (Statistics Canada, 2021).

For the purpose of clarity, any reference to boys, girls, male/female anatomy, physiology, or physical development in our readings refers to changes that occur based on the sex assigned at birth, unless otherwise noted.

Hormonal Changes

Puberty involves distinctive physiological changes in an individual’s height, weight, body composition, and circulatory and respiratory systems, and during this time, both the adrenal glands and sex glands mature. These changes are largely influenced by hormonal activity. Many hormones contribute to the beginning of puberty, but most notably a major rush of estrogen for girls and testosterone for boys. Hormones play an organizational role (priming the body to behave in a certain way once puberty begins) and an activational role (triggering certain behavioural and physical changes). During puberty, the adolescent’s hormonal balance shifts strongly towards an adult state; the process is triggered by the pituitary gland, which secretes a surge of hormonal agents into the blood stream and initiates a chain reaction.

Puberty occurs over two distinct phases, and the first phase, adrenarche, begins at 6 to 8 years of age and involves increased production of adrenal androgens that contribute to a number of pubertal changes—such as skeletal growth. The second phase of puberty, gonadarche, begins several years later and involves increased production of hormones governing physical and sexual maturation.

Sexual Maturation

During puberty, primary and secondary sex characteristics develop and mature. Primary sex characteristics are organs specifically needed for reproduction—the uterus and ovaries in females and testes in males. Secondary sex characteristics are physical signs of sexual maturation that do not directly involve sex organs, such as development of breasts and hips in girls, and development of facial hair and a deepened voice in boys. Both sexes experience development of pubic and underarm hair, as well as increased development of sweat glands.

The male and female gonads are activated by the surge of the hormones discussed earlier, which puts them into a state of rapid growth and development. The testes primarily release testosterone and the ovaries release estrogen; the production of these hormones increases gradually until sexual maturation is met.

For girls, observable changes begin with nipple growth and pubic hair. Then the body increases in height while fat forms particularly on the breasts and hips. The first menstrual period (menarche) is followed by more growth, which is usually completed by four years after the first menstrual period began. Girls experience menarche usually around 12–13 years old. For boys, the usual sequence is growth of the testes, initial pubic-hair growth, growth of the penis, first ejaculation of seminal fluid (spermarche), appearance of facial hair, a peak growth spurt, deepening of the voice, and final pubic-hair growth. (Herman-Giddens et al, 2012). Boys experience spermarche, the first ejaculation, around 13–14 years old.

Sexual Development

Developing sexually is an expected and natural part of growing into adulthood. Healthy sexual development involves more than sexual behaviour. It is the combination of physical sexual maturation (puberty, age-appropriate sexual behaviours), the formation of a positive sexual identity, and a sense of sexual well-being (discussed more in depth later in this module). During adolescence, teens strive to become comfortable with their changing bodies and to make healthy, safe decisions about which sexual activities, if any, they wish to engage in.

Earlier we discussed primary and secondary sex characteristics. During puberty, every primary sex organ (the ovaries, uterus, penis, and testes) increases dramatically in size and matures in function. During puberty, reproduction becomes possible. Simultaneously, secondary sex characteristics develop. These characteristics are not required for reproduction, but they do signify masculinity and femininity.

At birth, boys and girls have similar body shapes, but during puberty, males widen at the shoulders and females widen at the hips and develop breasts (examples of secondary sex characteristics). Sexual development is impacted by a dynamic mixture of physical and cognitive change coupled with social expectations. With physical maturation, adolescents may become alternately fascinated with and chagrined by their changing bodies, and often compare themselves to the development they notice in their peers or see in the media. For example, many adolescent girls focus on their breast development, hoping their breasts will conform to an “ideal” body image portrayed through social media (University of Alberta, 2022).

As the sex hormones cause biological changes, they also affect the brain and trigger sexual thoughts. Culture, however, shapes actual sexual behaviours. Emotions regarding sexual experience, like the rest of puberty, are strongly influenced by cultural norms regarding what is expected at what age, with peers being the most influential. Simply put, the most important influence on adolescents’ sexual activity is not their bodies, but their close friends, who have more influence than do sex or ethnic group norms (van de Bongardt et al., 2015).

Sexual interest and interaction are a natural part of adolescence. Sexual fantasy and masturbation episodes increase between the ages of 10 and 13. Masturbation is very ordinary—even young children have been known to engage in this behaviour. As the bodies of children mature, powerful sexual feelings begin to develop, and masturbation helps release sexual tension. For adolescents, masturbation is a common way to explore their erotic potential, and this behaviour can continue throughout adult life.

Gender, Sex, and Sexuality

Understanding inclusive terminology is essential in our work as Child and Youth Care Practitioners. Gender expression and gender identity have been protected grounds in the Ontario Human Rights Code since 2012 (Ontario Human Rights Commission, n.d.), and having this understanding allows us to appropriately support, share information with, and interact with young people.

As the onset of puberty begins around the teen years, we may work with young people who have questions, want to know more about, or want to explore their own identity and expression. The resources in this section provide more information when having these conversations. Being mindful of the environment is also important in our work as CYCPs.

“Rainbow Health Ontario (RHO), a program of Sherbourne Health, led a needs assessment to learn about ongoing concerns and challenges faced by trans and non-binary children and youth; their parents and caregivers; and their service providers. Evidently, significant barriers remain for these children and youth to have access to needed health care in a timely way, and to fully participate in their families, communities and broader society.” (RHO, 2019, p. i)

Become familiar with the following terms:

Gender can refer to the individual and/or social experience of being a man, a woman, or neither. Social norms, expectations and roles related to gender vary across time, space, culture, and individuals.

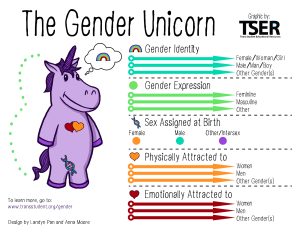

Gender identity (TSER, n.d.) is “one’s internal sense of being male, female, neither of these, both, or other gender(s). Everyone has a gender identity, including you. For transgender people, their sex assigned at birth and their gender identity are not necessarily the same.” The 519 (2020) defines this as the internal and individual experience of gender.

Gender expression includes “how a person publicly expresses or presents their gender. This can include behaviour and outward appearance such as dress, hair, make-up, body language, and voice. A person’s chosen name and pronoun are also common ways of expressing gender. All people, regardless of their gender identity, have a gender expression and they may express it in any number of ways” (The 519, 2020).

Sexual orientation (TSER, n.d.) is person’s physical, romantic, emotional, aesthetic, and/or other form of attraction to others. In Western cultures, gender identity and sexual orientation are not the same.

Sex assigned at birth “is the assignment and classification of people as male, female, intersex, or another sex assigned at birth often based on physical anatomy at birth and/or karyotyping” (testing to examine chromosomes) (TSER, n.d.).

Trans Student Education Resources has developed the Gender Unicorn (2015) to simplify the language and differences between the terms.

Want to learn more?

Brochure developed by RHO:

Brochure: Gender Affirming Options for Gender Independent Children and Adolescents

Glossary of terms developed by The 519 in Toronto:

Gegi.ca – resource providing information on how to advocate for gender identity and expression at schools in Ontario.

Sexual Interactions

Many early social interactions tend to be nonsexual—text messaging, phone calls, email—but by the age of 12 or 13, some young people may pair off and begin dating and experimenting with kissing, touching, and other physical contact, such as oral sex. The vast majority of young adolescents are not prepared emotionally or physically for oral sex and sexual intercourse. If adolescents this young do have sex, they are highly vulnerable for sexual and emotional abuse, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV, and early pregnancy (Canadian Paediatric Society, 2019). For STI’s in particular, adolescents are slower to recognize symptoms, tell partners, and get medical treatment, which puts them at risk of infertility and even death.

Link to Learning

Visit the Teen Health Source for more information on STIs, contraception, and sexual health (https://teenhealthsource.com/information/).

Adolescents ages 14 to 16 understand the consequences of unprotected sex and teen parenthood, if properly taught, but cognitively they may lack the skills to integrate this knowledge into everyday situations or consistently to act responsibly in the heat of the moment. By the age of 17, many adolescents have willingly experienced sexual intercourse. Teens who have early sexual intercourse report strong peer pressure as a reason behind their decision. Some adolescents are just curious about sex and want to experience it (Tulloch & Kaufman, 2013).

Becoming a sexually healthy adult is a developmental task of adolescence that requires integrating psychological, physical, cultural, spiritual, societal, and educational factors. It is particularly important to understand the adolescent in terms of his or her physical, emotional, and cognitive stage. Additionally, healthy adult relationships are more likely to develop when adolescent impulses are not shamed or feared. Guidance is certainly needed, but acknowledging that adolescent sexuality development is both normal and positive would allow for more open communication so adolescents can be more receptive to education concerning the risks (Tolman & McClelland, 2011).

Adolescents are receptive to their culture, to the models they see at home, in school, and in the mass media. These observations influence moral reasoning and moral behaviour, which we discuss in more detail later in this module. Decisions regarding sexual behaviour are influenced by teens’ ability to think and reason, their values, and their educational experience.

Having these conversations as CYCPs is one way to share relevant, factual information. The Ontario health and physical education curriculum (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2015) provides a framework for how to introduce these topics in an age and developmentally appropriate manner (though there has been a lot of controversy around this, click to read more). But this is still at the discretion of principals and teachers. Depending on the school board, the information adolescents receive may not be the full picture.

This is where we, as CYCPs, can support. Having an understanding about sex, healthy relationships, puberty, and development, we can help adolescents recognize all aspects of sexual development, which encourages them to make informed and healthy decisions about sexual matters, as well as their health and wellbeing overall.

References

Canadian Paediatric Society (2019). Diagnosis and management of sexually transmitted infections in adolescents. https://cps.ca/en/documents/position/sexually-transmitted-infections

Ontario Human Rights Commission (n.d.). Gender identity and gender expression. https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/code_grounds/gender_identity

Statistics Canada (2021). Sex at birth of person. https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Var.pl?Function=DEC&Id=24101

Teen Health Source (n.d.). Information. https://teenhealthsource.com/information/

The 519. (2020). Glossary of terms. https://www.the519.org/education-training/glossary/

Tolman, D.L. & McClelland, S.I. (2011). Normative sexuality development in adolescence; A decade in review, 2000-2009. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21 (1), 242-255.

Trans Student Educational Resources (2015). Gender unicorn. https://transstudent.org/gender/

Tulloch, T., & Kaufman, M. (2013). Adolescent sexuality. Pediatrics in Review, 34 (1) 29-38; DOI: 10.1542/pir.34-1-29

University of Alberta. (2022). LifeLines: The impact of social media on body image & mental health. https://www.ualberta.ca/human-resources-health-safety-environment/news/2022/01-january/february-2022-life-lines.html

van de Bongardt, D., Reitz, E., Sandfort, T. & Dekovic, J (2015). A meta-analysis of the relations between three types of peer norms and adolescent sexual behaviour. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19 (3), 203-234.