1 Social and Emotional Development in Preschool Children

Chapter Objectives

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explore how emotions and relationships emerge.

- Describe the concepts of self-esteem and self concept.

- Develop activities that promote social and emotional development.

Introduction

The preschooler is starting to solidify their self-concept, identity and self-esteem. They have improved their ability to recognize and express their emotions appropriately. A typically developing preschooler is developing the ability to regulate their attention, emotions and behaviour. These emerging competencies help them persevere when faced with challenges and cope when unsuccessful at a task.

Relationships between caregivers and children continue to play a significant role in children’s development during early childhood, and friendships continue to develop.

In the preschool years, children’s understanding of their role in the world expands greatly. Seeking out and making friends gains importance during the preschool years. This is facilitated by improved skills in conflict resolution, social problem-solving skills, peer group entry skills and co-operation. Preschoolers are more competent at identifying emotions in others, taking another person’s point of view, empathizing and offering help. These emerging competencies improve the preschooler’s ability to interact with others positively and respectfully. Preschoolers often seek out adult attention and approval and have developed the social skills to do so in a positive manner (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014). Social interaction with another child who is similar in age, skills, and knowledge provokes the development of many social skills that are valuable for the rest of life (Bukowski, Buhrmester, & Underwood, 2011, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Most children by age 5:

- Want to please and be liked by their friends, though they may sometimes be mean to others

- Agree to rules most of the time

- Have distinct ways of playing according to gender. Most 5-year-old boys play in rough or physically active ways. Girls of the same age are more likely to engage in social play

Relationships in preschool

Caregivers, siblings, extended family, teachers, and peers all have a role in social development for preschool children. These relationships can support the shaping of self-esteem and moral development, which we’ll cover later in this reading.

Family Life

Relationships between caregivers (e.g., parents) and children continue to play a significant role in children’s development during early childhood. Keep in mind that most parents do not follow any model completely. In reality, people tend to fall somewhere in between these styles. Sometimes, parenting styles change from one child to the next, or in times when the parent has more or less time and energy for parenting.

Note: For the purpose of this course, parents may not be a child’s biological parent, so we use the terms interchangeably. The research and theories discuss parenting; this refers to the act of raising a child and can refer to any adult caregiver in a child’s life.

Parenting Styles

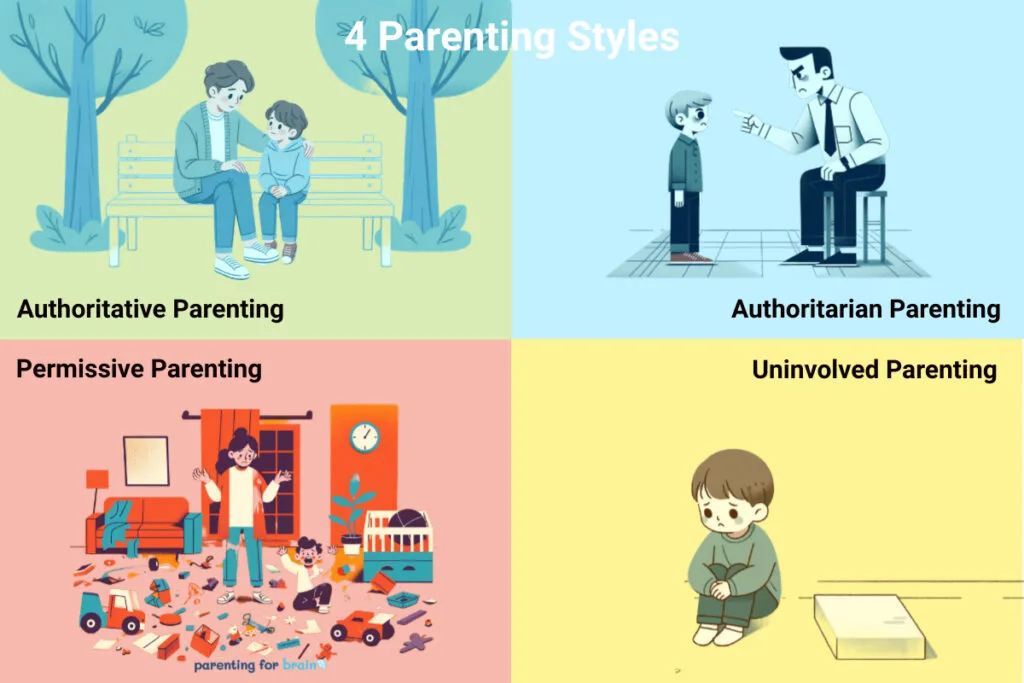

Diana Baumrind (1971, as cited in Paris et al., 2021) offers a model of parenting that includes four styles.

Authoritarian

The traditional model of parenting in which parents make the rules and children are expected to be obedient. Baumrind suggested that authoritarian parents tend to place maturity demands on their children that are unreasonably high and tend to be aloof and distant. Consequently, children reared in this way may fear rather than respect their parents and, because their parents do not allow discussion, may take out their frustrations on safer targets-perhaps as bullies toward peers.

Permissive parenting

Involves holding expectations of children that are below what could be reasonably expected from them. Children are allowed to make their own rules and determine their own activities. Parents are warm and communicative, but provide little structure for their children. Children fail to learn self-discipline and may feel somewhat insecure because they do not know the limits.

Authoritative parenting

Being appropriately strict, reasonable, and affectionate. Parents allow negotiation where appropriate and discipline matches the severity of the offense. In Ontario, many EarlyON Child and Family Centres offer parenting programs, including Triple P (Positive Parenting Program) and Nobody’s Perfect.

Uninvolved parents (also referred to as rejecting/neglecting)

Parents are disengaged from their children. They do not make demands on their children and are non-responsive. These children can suffer in school and in their relationships with their peers (Gecas & Self, 1991, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

Parenting styles can also be affected by concerns the parent has in other areas of their life. For example, parenting styles tend to become more authoritarian when parents are tired and perhaps more authoritative when they are more energetic. Sometimes, parents seem to change their parenting approach when others are around, maybe because they become more self-conscious as parents or are concerned with giving others the impression that they are a “tough” parent or an “easy-going” parent. And of course, parenting styles may reflect the type of parenting someone saw modelled while growing up.

What does it all mean?

The following article gives some insight into development in kindergarten and the impact on later development. Read the findings: Researchers studied kindergarteners’ behavior and followed up 19 years later (Upworthy, 2023). This article gives examples of what relationships with parents and siblings can mean for future development. Parental warmth and parental control and the combination of the two, leads to different parenting styles. Combining this with a child’s temperament, this can influence the parent-child relationship.

Remember Mary Ainsworth’s strange situation test when we talked about attachment? This outlined different forms of attachment, which is also influenced by the parent-child relationship, and goodness of fit.

Want to read more about parenting styles? Li (2023) expands on the four styles in the article: 4 Parenting Styles and Their Proven Impact on Kids

Cultural Influences on Parenting Styles

The impact of class and culture cannot be ignored when examining parenting styles. The parenting described above assume that authoritative are best because they are designed to help the parent raise a child who is independent, self-reliant and responsible. These are qualities favored in “individualistic” cultures.

According to Pye, Scoffin, Quade and Krieg (2022) in “collectivistic” cultures such as China or Korea, being obedient and compliant are favored behaviors. Authoritarian parenting has been used historically and reflects cultural need for children to do as they are told. In societies where family members’ cooperation is necessary for survival, as in the case of raising crops, rearing children who are independent and who strive to be on their own makes no sense. But in an economy based on being mobile in order to find jobs and where one’s earnings are based on education, raising a child to be independent is very important.

Working class parents are more likely than middle class parents to focus on obedience and honesty when raising their children. In a classic study on social class and parenting styles called Class and Conformity, Kohn (1977, as cited in Paris et al., 2021) explains that parents tend to emphasize qualities that are needed for their own survival when parenting their children. Working class parents are rewarded for being obedient, reliable, and honest in their jobs. They are not paid to be independent or to question the management; rather, they move up and are considered good employees if they show up on time, do their work as they are told, and can be counted on by their employers. Consequently, these parents reward honesty and obedience in their children.

Middle class parents who work as professionals are rewarded for taking initiative, being self-directed, and assertive in their jobs. They are required to get the job done without being told exactly what to do. They are asked to be innovative and to work independently. These parents encourage their children to have those qualities as well by rewarding independence and self-reliance. Parenting styles can reflect many elements of culture (Lumen Learning, 2021).

Indigenous Perspectives

Canadian First Nation cultural groups, while diverse, all stress the critical importance of parenting during the first seven years. “In addition to parenting our children, we also are parenting our grandchildren, those yet to be born.” (Best Start Resource Centre, 2010). Parents, extended family, elders and the community are all responsible for providing unconditional love and discipline. Children are encouraged to make their own decisions (from among acceptable choices) and allowed to make mistakes. Story-telling is used to help teach children important life lessons. Modeling desirable behavior is another key teaching tool. First Nations cultures strongly believe that children are to be treated as equals and never talked down, belittled or bribed as a form of discipline.

Due to the residential school legacy, laws have been put in place regarding the placement of children in non-indigenous families in foster care. For some but not all, the law states that the child will stay in the FN community whereby parents will go through cultural programming and healing to reintegrate the child back into the home. Also there is the issue of displacement for children from remote First Nation communities who do not have either elementary and/or secondary schools. Many grandparents or aunts and uncles decide to move out of the community to urban areas to take care of the children. Subsequently, other extended family members would be rearing the child or children.

Parenting styles are different in Indigenous people’s family life. For instance, in many nations, aunties and uncles are the ones who discipline the children to keep harmony in the home. Grandparents offer teachings and show cultural and traditional ways of life; they also sometimes discipline but in a different way.

Multigenerational Families

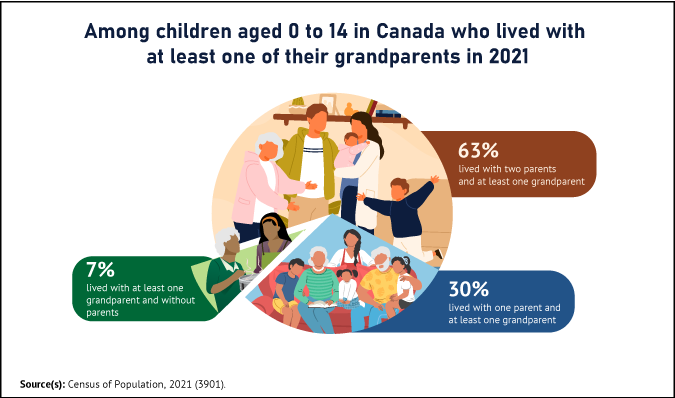

According to Statistics Canada (2022) using data from the most recent national census, in 2021 over half a million children (533,855 to be exact; that’s 9.3% of children in Canada!) lived in the same household as one of their grandparents. Over 93% of these children lived in a multigenerational household with at least one parent and one grandparent. (Statistics Canada, 2022). See more stats in figure 10.2 below.

There were significant differences found among various cultural groups. While current statistics have not emerged at the time this reading is available, previous studies through Statistics Canada (2015) demonstrated some of these differences. 11% of grandparents who identified as Indigenous (First Nations People, Metis or Inuit) lived with their grandchildren. This percentage increased to 22% in the Inuit population. 21% of recent immigrants to Canada (arriving between 2006 and 2011) aged 45 and older co-resided with grandchildren. These percentages are all significantly higher than the 3% of non-Indigenous Canadian-born grandparents who live in the same household as their grandchildren (Statistics Canada, 2015).

Today’s grandparent is healthier and will live longer than previous generations. While they may or may not co-reside with their grandchildren, many contribute to family life, perhaps choosing to provide child care or helping out financially. Evolving family composition has increased the need for non-parental child care. According to Statistics Canada (2015), in 2014, 69% of couples in Canada with children included 2 earners, up from just 36% in 1976. Likewise, the percentage of lone-parent families has increased from 1 in 10 in 1976 to approximately 1 in 5 in 2014.

Two factors can lead to grandparents being turned to for child care; lack of available, high quality, regulated child care and the cost. Availability varies among provinces and territories, but the need continues to far exceed availability across Canada. While there are many variables that go into the cost of child care (e.g.: urban versus rural, age of the child, centre-based versus home-based), as an example, “Ontario’s Early Years and Child Care Annual Report 2020” found median parent fees for licensed centre-based care ranged from $66/day for infants to $22/day for school-aged children (Province of Ontario, 2021). “Research shows that grandparent involvement in family life is significantly associated with child well-being, including greater prosocial behaviors and school involvement” (Vanier Institute, 2017). This is particularly true among First Nations families, where grandparents are valued for their role in supporting cultural well-being in younger generations.

Want to learn more?

If you’re interested in statistics (like me!) you can learn even more and explore the findings in more detail. Check out The Daily – Home alone: More persons living solo than ever before, but roomies the fastest growing household type. This is optional, and more for your interest!

Sibling Relationships

Siblings typically spend a considerable amount of time with each other and offer a unique relationship that is not found with same-age peers or with adults. Siblings play an important role in the development of social skills. Cooperative and pretend play interactions between younger and older siblings can teach empathy, sharing, and cooperation (Pike, Coldwell, & Dunn, 2005, as cited in Paris et al., 2021) as well as negotiation and conflict resolution (Abuhatoum & Howe, 2013, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). However, the quality of sibling relationships is often mediated by the quality of the parent-child relationship and the psychological adjustment of the child (Pike et al., 2005, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). For instance, more negative interactions between siblings have been reported in families where parents had poor patterns of communication with their children (Brody, Stoneman, & McCoy, 1994, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Children who have emotional and behavioral problems are also more likely to have negative interactions with their siblings.

While parents want positive interactions between their children, conflicts are going to arise, and some confrontations can be the impetus for growth in children’s social and cognitive skills. The sources of conflict between siblings often depend on their respective ages. Dunn and Munn (1987, as cited in Paris et al., 2021) revealed that over half of all sibling conflicts in early childhood were disputes about property rights. Researchers have also found that the strategies children use to deal with conflict change with age, but that this is also tempered by the nature of the conflict (Paris et al., 2021).

Not surprisingly, friendly relationships with siblings often lead to more positive interactions with peers. The reverse is also true. A child can also learn to get along with a sibling, with, as the song says “a little help from my friends” (Kramer & Gottman, 1992, as cited in Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Want to learn more? See Paris et. al. (2021) and their chapter on family life.

Peers

Relationships within the family (parent-child and siblings) are not the only significant relationships in a child’s life. Peer relationships are also important. Social interaction with another child who is similar in age, skills, and knowledge provokes the development of many social skills that are valuable for the rest of life (Bukowski et al., 2011, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). In peer relationships, children learn how to initiate and maintain social interactions with other children. They learn skills for managing conflict, such as turn-taking, compromise, and bargaining. Play also involves the mutual, sometimes complex, coordination of goals, actions, and understanding. For example, as preschoolers engage in pretend play they create narratives together, choose roles, and collaborate to act out their stories. Through these experiences, children develop friendships that provide additional sources of security and support to those provided by their parents.

However, peer relationships can be challenging as well as supportive (Rubin, Coplan, Chen, Bowker, & McDonald, 2011, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Being accepted by other children is an important source of affirmation and self-esteem, but peer rejection can foreshadow later behavior problems (especially when children are rejected due to aggressive behavior).

Peer relationships require developing very different social and emotional skills than those that emerge in parent-child relationships. They also illustrate the many ways that peer relationships influence the growth of personality and self-concept (Leon, n.d.).

Play and its role in social interactions

As we learned last week, pretending is a favourite activity at this time. A toy has qualities beyond the way it was designed to function and can now be used to stand for a character or object unlike anything originally intended. A teddy bear, for example, can be a baby or the queen of a faraway land!

Symbolic play ( also known as pretend or fantasy play) is a form of communication – children communicate with others using language gestures and symbolic objects to tell and retell stories (Berk & Winsler, 1995). Social competence, emotional and attention self-regulation and the ability to communicate with others are foundational to all types of learning and are best developed in play-based environments (Barnett et al., 2006; Ziegler, Singer & Bishop-Josef, 2005; Kagan & Lowenstein, 2004). Source: “Early Learning for Every Child Today”

Self-Control and Play

Thanks to the new Centre for Research on Play in Education, Development and Learning (PEDaL), Whitebread, Baker, Gibson and a team of researchers hope to provide evidence on the role played by play in how a child develops (as cited in Paris et al., 2021.

“A strong possibility is that play supports the early development of children’s self-control,” explains Baker. “These are our abilities to develop awareness of our own thinking processes – they influence how effectively we go about undertaking challenging activities.”

In a study carried out by Baker with toddlers and young preschoolers, she found that children with greater self-control solved problems quicker when exploring an unfamiliar set-up requiring scientific reasoning, regardless of their IQ.” This sort of evidence makes us think that giving children the chance to play will make them more successful and creative problem-solvers in the long run.”

If playful experiences do facilitate this aspect of development, say the researchers, it could be extremely significant for educational practices because the ability to self-regulate has been shown to be a key predictor of academic performance.

Gibson adds: “Playful behaviour is also an important indicator of healthy social and emotional development. In my previous research, I investigated how observing children at play can give us important clues about their well being and can even be useful in the diagnosis of neuro-developmental disorders like autism.”

Want to learn more? Read Play’s the Thing, by the University of Cambridge is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

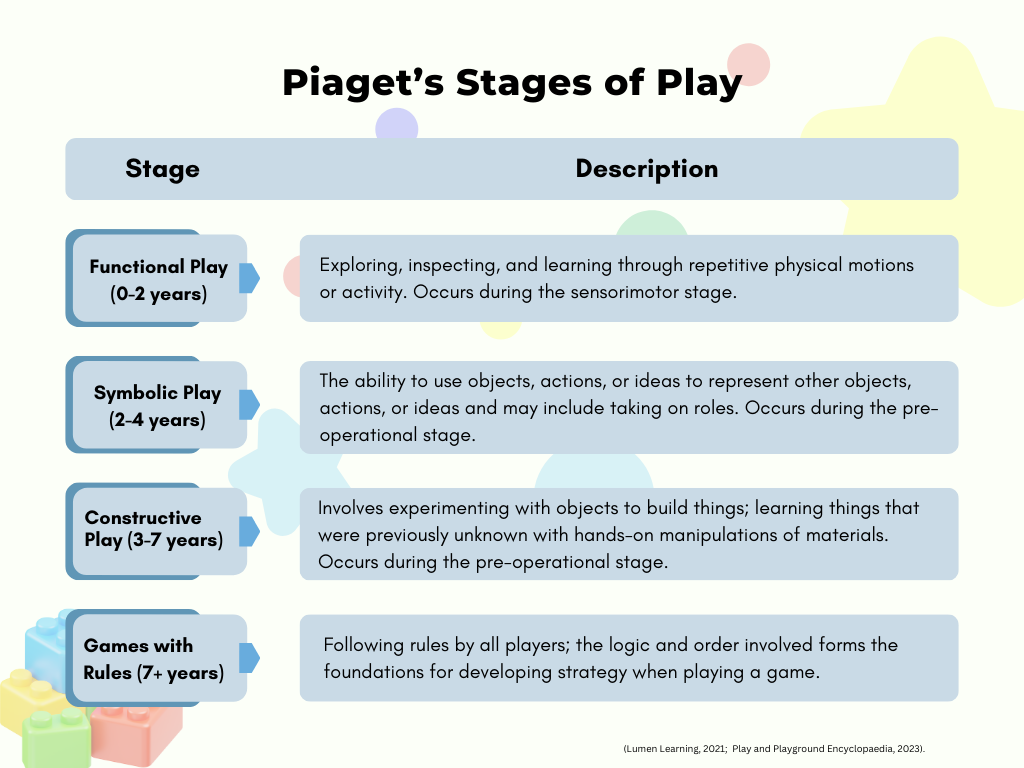

Piaget’s Stages of Play (Adapted from Grounds for Play, n.d., as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

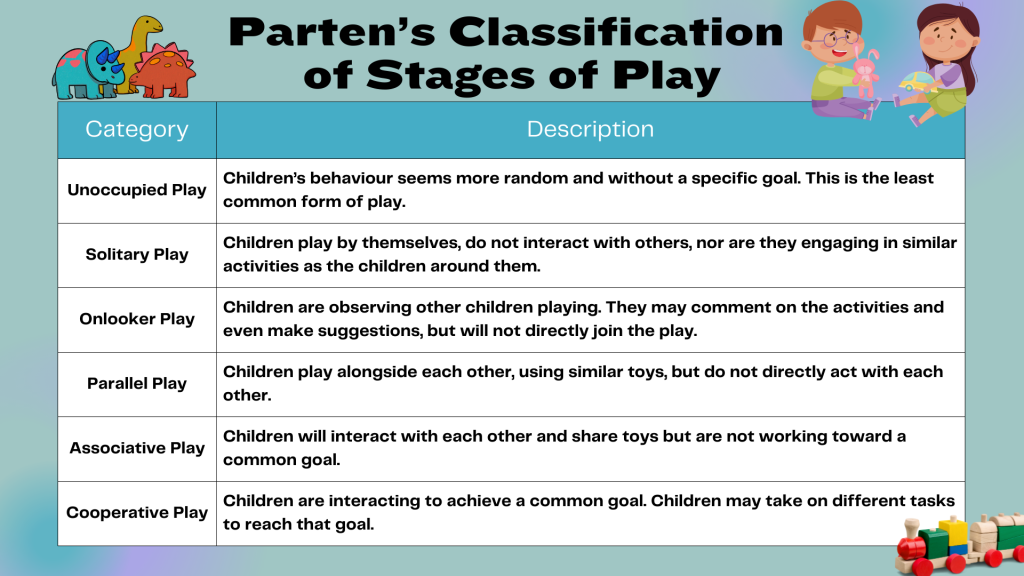

Mildred Parten (1932) observed children ages two to five years-old and noted six types of play. Three types she labeled as non-social (unoccupied, solitary, and onlooker) and three types were categorized as social play (parallel, associative, and cooperative). The table below describes each type of play. Younger children engage in non-social play more than those who are older; by age five associative and cooperative play are the most common forms of play (Dyer & Moneta, 2006, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

Parten’s Classification of Types of Play (adapted from Lumen Learning, 2021)

Understanding the different types of play is helpful when observing children on the playground, in the community, and speaks to the different levels of relationships we can be on the lookout for, and encourage developing, as CYCs.

Identity, self-esteem, and self concept

Early childhood is a time of forming an initial sense of self. Self-concept is our self-description according to various categories, such as our external and internal qualities. In contrast, self-esteem is an evaluative judgment about who we are. The emergence of cognitive skills in this age group results in improved perceptions of the self, but they tend to focus on external qualities, which are referred to as the categorical self. When researchers ask young children to describe themselves, their descriptions tend to include physical descriptors, preferred activities, and favorite possessions. Thus, the self-description of a 3-year-old might be a 3-year-old girl with red hair, who likes to play with blocks. However, even children as young as three know there is more to themselves than these external characteristics.

Harter and Pike (1984, as cited by Paris et al., 2021) challenged the method of measuring personality with an open-ended question as they felt that language limitations were hindering the ability of young children to express their self-knowledge. They suggested a change to the method of measuring self-concept in young children, whereby researchers provide statements that ask whether something is true of the child (e.g., “I like to boss people around”, “I am grumpy most of the time”). They discovered that in early childhood, children answer these statements in an internally consistent manner, especially after the age of four (Goodvin, Meyer, Thompson & Hayes, 2008, as cited by Paris et al., 2021) and often give similar responses to what others (parents and teachers) say about the child (Brown, Mangelsdorf, Agathen, & Ho, 2008; Colwell & Lindsey, 2003, as cited by Paris et al., 2021).

Young children tend to have a generally positive self-image. This optimism is often the result of a lack of social comparison when making self-evaluations (Ruble, Boggiano, Feldman, & Loeble, 1980, as cited by Paris et al., 2021), and with comparison between what the child once could do to what they can do now (Kemple, 1995). However, this does not mean that preschool children are exempt from negative self-evaluations. Preschool children with insecure attachments to their caregivers tend to have lower self-esteem at age four (Goodvin et al., 2008, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). Maternal negative affect (emotional state) was also found by Goodwin and her colleagues to produce more negative self-evaluations in preschool children.

In terms of self-esteem and self concept, Healthy Families BC has a great site that gives ideas for how to support self-esteem in preschool-aged children. If you’re interested, read through Growth and Development: Helping Your Child Build Self-Esteem. At this age children’s self-esteem can be high, the article talks about how we can support this to continue.

Caring for Kids, a site created by Canadian Pediatricians also has information on how to support. For ideas on how we can use play an activities and other interactions, read: How to foster your child’s self-esteem.

Moral Development

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/initiative-versus-guilt-2795737_final-13638da1c7694dbaa8659dcb4a958c15.jpg)

Erikson – Initiative Vs Guilt

Psychologist Erik Erikson argues that children in early childhood go through a stage of “initiative vs. guilt.” If the child is placed in an environment where they can explore, make decisions, and initiate activities, they have achieved initiative. On the other hand, if the child is put in an environment where initiation is repressed through criticism and control, they will develop a sense of guilt.

The trust and autonomy of previous stages develop into a desire to take initiative or to think of ideas and initiative action. Children may want to build a fort with the cushions from the living room couch or open a lemonade stand in the driveway or make a zoo with their stuffed animals and issue tickets to those who want to come. Or they may just want to get themselves ready for bed without any assistance. To reinforce taking initiative, caregivers should offer praise for the child’s efforts and avoid being critical of messes or mistakes. Soggy washrags and toothpaste left in the sink pales in comparison to the smiling face of a five-year-old that emerges from the bathroom with clean teeth and pajamas! (Leon, n.d.).

Preschoolers are beginning to be able to understand the difference between moral rules and social conventions. Moral rules are non-negotiable; for example, it is wrong to steal or murder. Social conventions are more arbitrary rules that a group has agreed upon; for example, standing in a line to board a bus. It is typical for children to test the limits of social conventions to learn what behavior is allowed and what will not be allowed. How adults respond to testing of limits is important. Dr. Smith believes “Preschool children do not fully understand the responsibility for repairing a wrong. Being forced to say, “I’m sorry” can become a magic incantation of absolution, as though words alone are enough to free them from the consequences of their choices” (Smith, n.d.). Children learn to truly care about others through their own relationships with caring adults.

Social and Emotional Competence

Social and personality development is built from the social, biological, and representational influences discussed above. These influences result in important developmental outcomes that matter to children, parents, and society: a young adult’s capacity to engage in socially constructive actions (helping, caring, sharing with others), to curb hostile or aggressive impulses, to live according to meaningful moral values, to develop a healthy identity and sense of self, and to develop talents and achieve success in using them. These are some of the developmental outcomes that denote social and emotional competence.

These achievements of social and personality development derive from the interaction of many social, biological, and representational influences. Consider, for example, the development of conscience, which is an early foundation for moral development.

Conscience consists of the cognitive, emotional, and social influences that cause young children to create and act consistently with internal standards of conduct (Kochanska, 2002, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). It emerges from young children’s experiences with parents, particularly in the development of a mutually responsive relationship that motivates young children to respond constructively to the parents’ requests and expectations. Biologically based temperament is involved, as some children are temperamentally more capable of motivated self-regulation (a quality called effortful control) than are others, while some children are more prone to the fear and anxiety that parental disapproval can evoke. The development of conscience is influenced by having a good fit between the child’s temperamental qualities and how parents communicate and reinforce behavioral expectations.

The development and awareness of a conscience also expands as young children begin to represent moral values and think of themselves as moral beings. By the end of the preschool years, for example, young children develop a “moral self” by which they think of themselves as people who want to do the right thing, who feel badly after misbehaving, and who feel uncomfortable when others misbehave. In the development of conscience, young children become more socially and emotionally competent in a manner that provides a foundation for later moral conduct (Thompson, 2012, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Gender Identity and Roles

Another important dimension of the self is the sense of self with regard to gender.

Differences between boys and girls* both physically and in terms of what activities are acceptable for each. While 2-year-olds can identify some differences and learn whether they are boys or girls, preschoolers become more interested in what it means to be male or female. This self-identification or gender identity is followed sometime later with gender constancy or the knowledge that gender does not change. Gender roles or the rights and expectations that are associated with being male or female are learned throughout childhood and into adulthood.

Attraction begins in later years, but kids may still have questions about this. Caring for Kids, a site created by Canadian Pediatricians also has more information on gender identity and best practices that CYCPs can also incorporate into practice.

Learning theorists suggest that gender role socialization is a result of the ways in which parents, extended family, teachers, friends, schools, religious institutions, media and others send messages about what is acceptable or desirable behaviour as males or females. This socialization begins early-in fact, it may even begin the moment a parent learns that a child is on the way. Knowing the sex of the child can conjure up images of the child’s behaviour, appearance, and potential on the part of some parents. And this stereotyping may continue to guide perception through life.

*There is very little, general information about gender roles and gender identity available, but even less information about gender expression in children. Many resources (such as the description above) only describe two genders.

The Genderbread Unicorn gives a more thorough overview, and provides definitions and information that can be helpful supporting children who are begin to ask questions or want to explore their gender identity and expression. Another great resource is Pflag with local chapters around North America. The Toronto chapter provides many local resources to support the conversation.

Indigenous Perspectives

Gender identity is not something that is/was important to First Nation communities, but rather for the gifts that individual brought to the greater community. The term Two Spirit is a pan Indian term that was created in 1990s by non-Indigenous people. In many teachings, individuals who fall under the LGBTQ are regarded as two spirited. Two Spirit individuals are wanting to reclaim the pre-colonial teachings.

“Historically, each nation had their own terms and concepts for Two Spirit people. The roles of the Two Spirit people were teachers, caregivers, medicine people and helpers. They were highly respected for their understanding of both man and woman. They were also seen as having special spiritual gifts.” (Supporting the Sacred Journey, as cited in Pye et al., 2022). There is also a well-respected knowledge keeper called Albert McLeod who has worked tirelessly for the rights of the Two-Spirit community.

Gender messages are seen throughout Indigenous ceremonies. For example, boy’s and girl’s responsibilities are taught as early as 1 year-old during the Walking Out ceremony, carried out by the Anishinaabe people. These are not seen as stereotypical but rather what Creator is asking of us. For instance, a boy is taught that he is the protector and the hunter with the responsibility of the fire during ceremony in patriarchal societies. As for the girl, she is responsible for cooking, rearing the children, showing the children what is expected of them and protecting the water in life and in ceremony. Both genders are taught to be strong, active, rational, and respectful of the other gender including Two Spirit people. The girls are not taught that they are subordinate, unintelligent or just a pretty thing. Today it is not uncommon to see young girls taught to hunt, trap or fish or young men to take care of the children. There is more a sense of community and of respect towards all genders.

Gender messages abound in our environment. The Western stereotypes that boys should be strong, forceful, active, dominant, and rational and that girls should be pretty, subordinate, unintelligent, emotional, and gabby are portrayed in children’s toys, books, commercials, video games, movies, television shows and music.

Some School Boards in Ontario have developed policies and best practices concerning gender identity and gender expression. For example, the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board’s document “Gender Identity and Gender Expression: Guide to Support Our Students” expects its educators to challenge gender stereotypes. Specific actions include:

- Letting all students engage in an activity, not limit the number of boys or girls in a group.

- Encouraging students to take on various roles in a group.

- Avoiding separating boys and girls for activities (e.g. boys go to the gym and girls go to the library)

Avoiding giving out awards based on gender (e.g. Most books read by a boy in a month versus most books read by a girl in a month) - Intervening when children use gender-specific words to make fun of each other (Ottawa Carleton District School Board, 2021). But does this mean that each of us receives and interprets these messages in the same way? Probably not. In addition to being recipients of Western cultural expectations, we are individuals who also modify these roles (Kimmel, 2008, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Based on what young children learn about gender from parents, peers, media and those who they observe and interact with in society, children develop their own conceptions of the attributes associated with maleness or femaleness which is referred to as gender schemas.

Summary

- Explore how emotions and relationships emerge.

- Describe the concepts of self-esteem and self concept.

- Develop activities that promote social and emotional development.

References

Best Start Resource Centre (2010). A child becomes strong: Journeying through each stage of the life cycle. Retrieved from http://docplayer.net/27962989-A-child-becomes-strong-journeying-through-each-stage-of-the-life-cycle.html.

Caring for Kids. (2018). How to foster your child’s self-esteem. Retrieved from https://caringforkids.cps.ca/handouts/behavior-and-development/foster_self_esteem

HealthLinkBC. (2023). Growth and Development: Helping Your Child Build Self-Esteem. Retrieved from https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/pregnancy-parenting/relationships-and-emotional-health/growth-and-development-helping-your-child

Lally, M. & Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan development: A psychological perspective (2nd ed.). Retrieved from http://dept.clcillinois.edu/psy/LifespanDevelopment.pdf

Leon, A. (n.d.). Children’s development: Prenatal through adolescent development. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/document/d/1k1xtrXy6j9_NAqZdGv8nBn_I6-lDtEgEFf7skHjvE-Y/edit

Li, P. (2023). 4 Parenting Styles and Their Proven Impact on Kids. https://www.parentingforbrain.com/4-baumrind-parenting-styles/

Lumen Learning. (2021). Introduction to emotional and social development in early childhood. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/chapter/introduction-to-emotional-and-social-development-in-early-childhood/

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). Excerpts from “ELECT”. Retrieved from https://www.dufferincounty.ca/sites/default/files/rtb/Excerpts-from-Early-Learning-for-Every-Child-Today.pdf

Paris, J., Ricardo, A., Rymond, A., & Johnson, A. (2021). Child Growth and Development. Retrieved from https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Early_Childhood_Education/Book%3A_Child_Growth_and_Development_(Paris_Ricardo_Rymond_and_Johnson)

Province of Ontario. (2021). Ontario’s early years and child care annual report 2020. Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontarios-early-years-and-child-care-annual-report-2020

Pye, T., Scoffin, S., Quade, J., & Krieg, J. (2022). Child Growth and Development Canadian Ed. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/childgrowthanddevelopment/

Statistics Canada. (2022). The Daily – Home alone: More persons living solo than ever before, but roomies the fastest growing household type. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220713/dq220713a-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2015). Study: Grandparents living with their grandchildren, 2011. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/150414/dq150414a-eng.pdf?st=qilY03R4

Upworthy. (2023). Researchers studied kindergarteners’ behavior and followed up 19 years later. Here are the findings. https://www.upworthy.com/researchers-studied-kindergarteners-behavior-and-followed-up-19-years-later-here-are-the-findings

Vanier Institute. (2017). Grandparent health and family well-being. Retrieved from https://vanierinstitute.ca/grandparent-health-and-family-well-being/

OER Attributions:

Content from this reading has been adapted from the following sources:

Child Growth and Development Canadian Ed (2022) by Tanya Pye; Susan Scoffin; Janice Quade; and Jane Krieg is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Child Growth and Development by Paris, Ricardo, Rymond, and Johnson is shared under a CC BY license, except where otherwise noted.

Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning (2021) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Lifespan Development – A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license, except where otherwise noted.