Infants and Toddlers: Social and Emotional Development

Chapter Objectives

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explore how emotions develop.

- Describe the expression and regulation of emotions.

- List the stages of play and their importance.

- Identify the role of attachment at this stage.

Introduction

During the first three years of life, children are developing the ability to express and regulate their emotions. They are in the process of developing a sense of self. The ability to see things from another’s perspective (empathy) is beginning to emerge, and are able to express emotions that reflect these abilities.

The early interactions infants and toddlers have with adult caregivers (based on attachment theory) are necessary for the healthy development of social relationships. Infants and toddlers are developing the ability to express and regulate their emotions, determining their relationship with caregivers, and beginning to interact with each other as they get into the toddler years. They are in the process of developing a sense of self, and the ability to see things from another’s perspective (empathy) is beginning to emerge.

For Child and Youth Care Practitioners (CYCPs) this understanding of how emotions and social interactions develop provide us the foundational knowledge that guides how we support healthy development. While we work with children and youth at various ages, the milestones that can be expected during infancy and toddlerhood allow us to determine areas a child or youth may benefit from developing further. These milestones also inform our practice, as we can adapt our activities, interventions, interactions, and develop relationships to focus on areas of social and emotional development that require attention and further growth.

Let’s explore social and emotional development in more detail.

Emotional Development

What are emotions, and why are they important to our work as CYCPs? Emotions are what we feel, and emotion expression is how we demonstrate these feelings externally. Having an understanding of emotions, and how and when they develop is important for our work, as there is so much context we can use within our activities, interventions, and relationships.

The primary emotions we feel in our first year of life are joy, anger, fear, and sadness, or, four of the five characters from Inside Out:

From birth to 24 months of age, infants and toddlers can express a wide range of basic emotions, starting with the primary emotions, expanding to discomfort, pleasure, and excitement as they grow. Emotions are often divided into two general categories:

Primary emotions (basic emotions), such as interest, happiness, anger, fear, joy, surprise, sadness and disgust, appear first.

Secondary emotions (self-conscious emotions), such as envy, pride, shame, guilt, doubt, and embarrassment are expressed by around age two, and a child’s mental representation about the “self” is acquired.

Unlike primary emotions, secondary emotions appear as children start to develop a self-concept and require social instruction on when to feel such emotions. The situations in which children learn self-conscious emotions varies from culture to culture. Individualistic cultures teach us to feel pride in personal accomplishment, while in more collective cultures children are taught to not call attention to themselves, unless you wish to feel embarrassed for doing so (Akimoto & Sanbinmatsu, 1999, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Rymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Anger is often the reaction to being prevented from obtaining a goal, such as a toy being removed (Braungart-Rieker, Hill-Soderlund, & Karrass, 2010, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). In contrast, sadness is typically the response when infants are deprived of a caregiver (Papousek, 2007, as cited by Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Fear is often associated with the presence of a stranger, known as stranger wariness, or the departure of significant others known as separation anxiety. Both appear sometime between 6 and 15 months after object permanence has been acquired. Further, there is some indication that infants may experience jealousy as young as 6 months of age (Hart & Carrington, 2002, as cited by Pye, Scoffin, Quade & Krieg, 2022). Infants are developing attachments to primary caregivers and may show some hesitation or anxiety when separated from the important caregivers and adults in their lives (read more about attachment later in this reading). Infants have strategies to comfort themselves (e.g. thumb sucking) which helps them recover from stressful situations. They are beginning to develop a sense of self as they become more aware of their ability to make things happen. Older infants will notice when someone else appears upset and may offer some sort of comfort.

Development, expression, and regulation of emotions

The Continuum of Development (2007) identifies several root emotional skills that are emerging in children from birth to approximately 3 years of age (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014).

At birth, infants exhibit two emotional responses: attraction and withdrawal. They show attraction to pleasant situations that bring comfort, stimulation, and pleasure, and they withdraw from unpleasant stimulation such as bitter flavours or physical discomfort. Infants have strategies to comfort themselves (e.g. thumb sucking) which helps them recover from stressful situations. Infants begin to develop a sense of self as they become more aware of their ability to make things happen.

At around two months, infants exhibit social engagement in the form of social smiling as they respond with smiles to those who engage their positive attention (Lavelli & Fogel, 2005, as cited by Paris et al., 2021).

Social smiling becomes more stable and organized as infants learn to use their smiles to engage their caregivers in interactions. Pleasure is expressed as laughter at 3 to 5 months of age, and displeasure becomes more specific as fear, sadness, or anger between ages 6 and 8 months.

Older infants will notice when someone else appears upset and may offer some sort of comfort, and later in this section you’ll learn about attachment to caregivers and how infants react when separated from their caregivers.

Toddlers start to experience and express more complex, self-conscious emotions such as shame, guilt and pride. While infants use physical strategies for self-soothing, toddlers are starting to use language to help regulate their emotions. They are also beginning to regulate their behaviour by following verbal cues from others. Toddlers still find it challenging to pay attention without being easily distracted. Awareness of how someone else might be feeling is improving. Toddlers have a strong sense of self and need for autonomy, often manifested with a strong “no” when asked to do something.

Facial expressions of emotion are important regulators of social interaction. In the developmental literature, this concept has been investigated under the concept of social referencing; that is, the process whereby infants seek out information from others to clarify a situation and then use that information to act (Klinnert, Campos, & Sorce, 1993, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). To date, the strongest demonstration of social referencing comes from work on the visual cliff. In the first study to investigate this concept, Capos and colleagues (Sorce, Emde, Campos, & Klinnert, 1985, as cited by Pye et al., 2022) placed mothers on the far end of the “cliff” from the infant. Mothers first smiled to the infants and placed a toy on top of the safety glass to attract them; infants invariably began crawling to their mothers. When the infants were in the centre of the table, however, the mother then posed an expression of fear, sadness, anger, interest, or joy. The results were clearly different for the different faces; no infant crossed the table when the mother showed fear; only 6% did when the mother posed anger, 33% crossed when the mother posed sadness, and approximately 75% of the infants crossed when the mother posed joy or interest.

Other studies provide similar support for facial expressions as regulators of social interaction. Researchers posed facial expressions of neutral, anger, or disgust toward babies as they moved toward an object and measured the amount of inhibition the babies showed in touching the object (Bradshaw, 1986, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). The results for 10- and 15-month olds were the same: Anger produced the greatest inhibition, followed by disgust, with neutral the least. This study was later replicated using joy and disgust expression, altering the method so that the infants were not allowed to touch the toy (compared with a distractor object) until one hour after exposure to the expression (Hertenstein & Campos, 2004, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). At 14 months of age, significantly more infants touched the toy when they saw joyful expressions, but fewer touched the toy when the infants saw disgust.

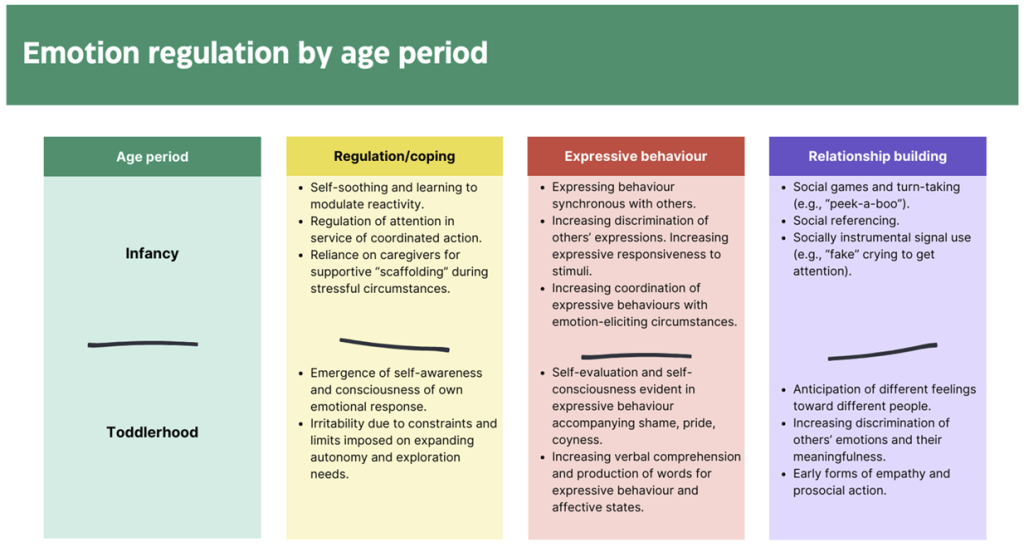

A significant emotional change is in self-regulation. Emotional self-regulation refers to strategies we use to control our emotional states so that we can attain goals (Thompson & Goodvin, 2007, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). This requires effortful control of emotions and initially requires assistance from caregivers (Rothbart, Posner, & Kieras, 2006, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). Table 7.1 below describes how this comes together by age group. Young infants have very limited capacity to adjust their emotional states and depend on their caregivers to help soothe them. Caregivers can offer distractions to redirect the infant’s attention and comfort to reduce the emotional distress. As areas of the infant’s prefrontal cortex continue to develop, infants can tolerate more stimulation. By 4 to 6 months, babies can begin to shift their attention away from upsetting stimuli (Rothbart et al, 2006). Older infants and toddlers can more effectively communicate their need for help and can crawl or walk toward or away from various situations (Cole, Armstrong, & Pemberton, 2010, as cited by Pye et al., 2022). This aids in their ability to self-regulate. Temperament also plays a role in children’s ability to control their emotional states, and individual differences have been noted in the emotional self-regulation of infants and toddlers (Rothbart & Bates, 2006, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

Canadian researcher Dr. Stuart Shanker has written extensively about the young child’s emerging ability to self-regulate. He defines self-regulation as “how efficiently and effectively a child deals with a stressor and then recovers” (Shanker, 2013). We start laying the foundation for development of this skill when we use calming strategies with a newborn baby. As the prefrontal cortex grows, the social engagement between adult and child becomes more complex. Toddlers begin to develop the language skills (expressive and receptive) needed for self-regulation. Shanker believes that, instead of rewarding or punishing children in order to get them to do what we want, we must help with the development of self-regulation skills by:

- identifying the underlying stressor or stressors,

- reducing those stressors, and

- teaching children strategies for calming themselves.

Rewards and punishment may temporarily result in a change in a child’s behaviour, but they have little long-term effect because they do not address why the child is displaying the undesired behaviour (Shanker, 2013).

Knowing the Self: The Development of the Self-Concept

One of the important milestones in a child’s social development is learning about his or her own self-existence (Figure 7.4). This self-awareness is known as consciousness, and the content of consciousness is known as the self-concept. The self-concept is a knowledge representation or schema that contains knowledge about us, including our beliefs about our personality traits, physical characteristics, abilities, values, goals, and roles, as well as the knowledge that we exist as individuals (Kagan, 1991).

Development of sense of self: During the second year of life, children begin to recognize themselves as they gain a sense of self as separate from their primary caregiver. In a classic experiment by Lewis and Brooks (1978 as cited in Walinga & Stagnor, 2014) children 9 to 24 months of age were placed in front of a mirror after a spot of rouge was placed on their nose as their mothers pretended to wipe something off the child’s face. If the child reacted by touching his or her own nose rather than that of the ‘baby “in the mirror, it was taken to suggest that the child recognized the reflection as him or herself. Lewis and Brooks found that somewhere between 15 and 24 months most infants developed a sense of self-awareness. Self-awareness is the realization that you are separate from others (Kopp, 2011, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). Once a child has achieved self-awareness, the child is moving toward understanding social emotions such as guilt, shame or embarrassment, as well as sympathy or empathy (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Some animals, including chimpanzees, orangutans, and perhaps dolphins, have at least a primitive sense of self (Boysen & Himes, 1999). In one study (Gallup, 1970), researchers painted a red dot on the foreheads of anesthetized chimpanzees and then placed each animal in a cage with a mirror. When the chimps woke up and looked in the mirror, they touched the dot on their faces, not the dot on the faces in the mirror. These actions suggest that the chimps understood that they were looking at themselves and not at other animals, and thus we can assume that they are able to realize that they exist as individuals. On the other hand, most other animals, including, for instance, dogs, cats, and monkeys never realize that it is themselves in the mirror.

Infants who have a similar red dot painted on their foreheads recognize themselves in a mirror in the same way that the chimps do, and they do this by about 18 months of age (Povinelli, Landau, & Perilloux, 1996). The child’s knowledge about the self continues to develop as the child grows. By age two, the infant becomes aware of his or her sex, as a boy or a girl. By age four, self-descriptions are likely to be based on physical features, such as hair colour and possessions, and by about age six, the child is able to understand basic emotions and the concepts of traits, being able to make statements such as “I am a nice person” (Harter, 1998).

Soon after children enter school (at about age five or six), they begin to make comparisons with other children, a process known as social comparison. For example, a child might describe himself as being faster than one boy but slower than another (Moretti & Higgins, 1990). According to Erikson, the important component of this process is the development of competence and autonomy — the recognition of one’s own abilities relative to other children. And children increasingly show awareness of social situations — they understand that other people are looking at and judging them the same way that they are looking at and judging others (Doherty, 2009).

This awareness and sense of self can also provide insight into a child’s personality and temperament.

Parenting is Bidirectional

Not only do caregivers affect children, children influence their caregivers. A child’s characteristics, such as temperament, affect parenting behaviours and roles. For example, an infant with an easy temperament may enable caregivers to feel more effective, as they are easily able to soothe the child and elicit smiling and cooing. On the other hand, a cranky or fussy infant elicits fewer positive reactions from his or her caregivers and may result in caregivers feeling less effective in the parenting role (Eisenberg et al., 2008, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). Over time, caregivers of more difficult children may become more punitive and less patient with their children (Clark, Kochanska, & Ready, 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Kiff, Lengua, & Zalewski, 2011, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). Caregivers who have a fussy, difficult child are less satisfied with their marriages and have greater challenges in balancing work and family roles (Hyde, Else-Quest, & Goldsmith, 2004, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). Thus, child temperament is one of the child characteristics that influences how caregivers behave with their children.

Bandura (1986, as cited by Lally and Valentine-French, 2019) suggests that there is interplay between the environment and the individual. We are not just the product of our surroundings, rather we influence our surroundings. There is interplay between our personality and the way we interpret events and how they influence us. This concept is called reciprocal determinism. An example of this might be the interplay between caregivers and children. Caregivers not only influence their child’s environment, perhaps intentionally through the use of reinforcement, etc., but children influence caregivers as well. Caregivers may respond differently with their first child than with their fourth. Perhaps they try to be the perfect caregivers with their first child, but by the time their last child comes along they have very different expectations both of themselves and their child. Our environment creates us and we create our environment.

Image 7.5: A smiling infant playing with toys. (Image by OmarMedinaFilms on Pixabay)

Goodness of Fit

Goodness of fit is a term borrowed from statistics to describe the compatibility between a person’s temperament and their surrounding environment. There are two aspects involved: how the trait interacts with the environment and how it interacts with the people in that environment. Any trait itself is not a problem, but it is the degree to which that trait is accepted that determines the goodness of fit. When the child’s temperament, skills and abilities match the expectations of the environment well this supports success and positive self-esteem. A good match is more likely to result in the child being successful. Success contributes to the development of healthy self-esteem and social relationships.

A mismatch between a child’s characteristics, the environment and/or the child’s primary caregivers can create stress and conflict for both the child and the caregivers. Responsive caregivers who accurately read the child will enjoy a goodness-of-fit, meaning their styles match and communication and interaction can flow. Examples: a naturally active child who lives in a small apartment compared to a child who lives in a larger home with a large back yard (Center for Parenting Education, n.d.).

Caring and responsive adults respect the child’s characteristics and assess themselves and the child’s environment to determine what could be changed to ensure a better match.

Indigenous Perspective

A toddler’s responsibility is about safety. As they explore the world around them, they like touching everything; hence learning through their interactions with the environment. Indigenous children are encouraged to explore the environment around them; especially outdoors to further their connection to the land.

Temperament

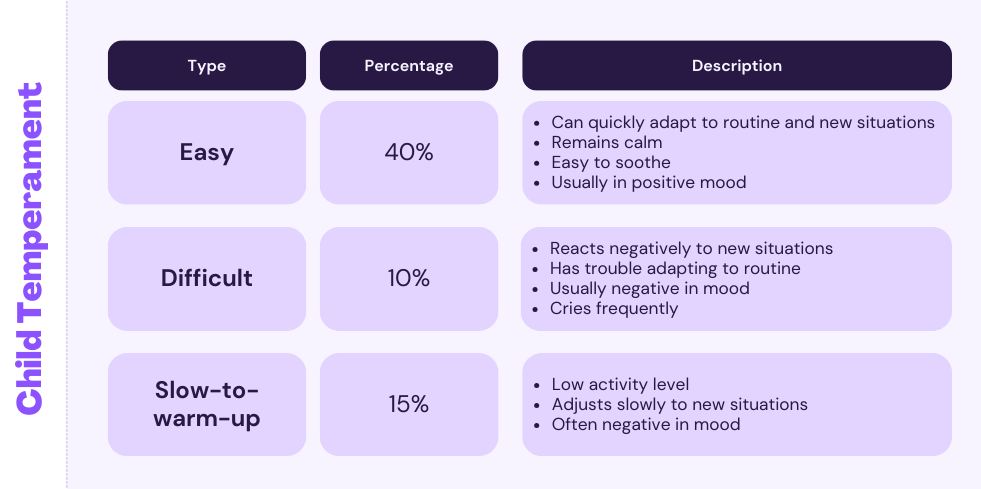

A child’s temperament will influence how the caregivers respond to them. Thomas, Chess, & Birch (1985 as cited in ) identified three temperaments – easy, difficult and slow to warm up.

Perhaps you have spent time with a number of infants. How were they alike? How did they differ? How do you compare with your siblings or other children you have known well? You may have noticed that some seemed to be in a better mood than others and that some were more sensitive to noise or more easily distracted than others. These differences may be attributed to temperament. Temperament is the innate characteristics of the infant, including mood, activity level, and emotional reactivity, noticeable soon after birth.

In a 1956 landmark study, Chess and Thomas (1996, as cited by Paris et al., 2021) evaluated 141 children’s temperament based on parental interviews. In what is referred to as the New York Longitudinal Study, infants were assessed on 10 dimensions of temperament including:

Activity level

- Rhythmicity (regularity of biological functions)

- Approach/withdrawal (how children deal with new things)

- Adaptability to situations

- Intensity of reactions

- Threshold of responsiveness (how intense a stimulus has to be for the child to react)

- Quality of mood

- Distractibility

- Attention span

- Persistence

Based on the infants’ behavioural profiles, they were categorized into three general types of temperament:

Table 7.2 Types of Temperament (Paris et al., 2021)

As can be seen in Table 7.2, the percentages of types of temperament do not equal 100% as some children were not able to be placed neatly into one of the categories. Think about how each type of child should be approached to improve interactions with them. An easy child requires less intervention, but still has needs that must not be overlooked. A slow-to-warm-up child may need to be given advance warning if new people or situations are going to be introduced. A child with a difficult temperament may need to be given extra time to burn off their energy. Caregivers who recognize each child’s temperament and accept it, will nurture more effective interactions with the child and encourage more adaptive functioning (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Personality

Temperament does not change dramatically as we grow up, but we may learn how to work around and manage our temperamental qualities. Temperament may be one of the things about us that stays the same throughout development. In contrast, personality, defined as an individual’s consistent pattern of feeling, thinking, and behaving, is the result of the continuous interplay between biological disposition and experience.

Personality also develops from temperament in other ways (Thompson, Winer, & Goodvin, 2010, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). As children mature biologically, temperamental characteristics emerge and change over time. A newborn is not capable of much self-control, but as brain-based capacities for self-control advance, temperamental changes in self-regulation become more apparent. For example, a newborn who cries frequently doesn’t necessarily have a grumpy personality; over time, with sufficient parental support and increased sense of security, the child might be less likely to cry.

In addition, personality is made up of many other features besides temperament. Children’s developing self-concept, their motivations to achieve or to socialize, their values and goals, their coping styles, their sense of responsibility and conscientiousness, as well as many other qualities are encompassed into personality. These qualities are influenced by biological dispositions, but even more by the child’s experiences with others, particularly in close relationships, that guide the growth of individual characteristics. Indeed, personality development begins with the biological foundations of temperament but becomes increasingly elaborated, extended, and refined over time. The newborn that caregivers gazed upon thus becomes an adult with a personality of depth and nuance (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Cultural and Gender Variations

Within a culture there are norms and behavioural expectations. These cultural norms can dictate which personality traits are considered important. The researcher Gordon Allport considered culture to be an important influence on traits and defined common traits as those that are recognized within a culture. These traits may vary from culture to culture based on differing values, needs, and beliefs. Positive and negative traits can be determined by cultural expectations: what is considered a positive trait in one culture may be considered negative in another, thus resulting in different expressions of personality across cultures.

Considering cultural influences on personality is important because Western ideas and theories are not necessarily applicable to other cultures (Benet-Martinez & Oishi, 2008, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). There is a great deal of evidence that the strength of personality traits varies across cultures, and this is especially true when comparing individualist cultures (such as European, North American, and Australian cultures) and collectivist cultures (such as Indigenous, French, Asian, African, and South American cultures). People who live in individualist cultures tend to believe that independence, competition, and personal achievement are important. In contrast, people who live in collectivist cultures tend to value social harmony, respectfulness, and group needs over individual needs. These values influence personality in different but substantial ways; for example, Yang (2006, as cited by Paris et al., 2021) found that people in individualistic cultures displayed more personally-oriented personality traits, whereas people in collectivist cultures displayed more social-oriented personality traits (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

In much the same manner that cultural norms can influence personality and behaviour, gender norms (the behaviours that males and females are expected to conform to in a given society) can also influence personality by emphasizing different traits between different genders – see images 7.7 and 7.8).

Ideas of appropriate behaviour for each gender (referring to gender assigned at birth) vary among cultures and tend to change over time. For example, aggression and assertiveness have historically been emphasized as positive masculine personality traits in Western cultures. Meanwhile, submissiveness and caretaking have historically been held as ideal feminine traits. While many gender roles remain the same, others change over time. In 1938, for example, only 1 out of 5 Americans agreed that a married woman should earn money in industry or business. By 1996, however, 4 out of 5 Americans approved of women working in these fields. This type of attitude change has been accompanied by behaviour shifts that coincide with changes in trait expectations and shifts in personal identity for men and women (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Social Development

It is through the remarkable increases in cognitive ability that children learn to interact with and understand their environments. But these cognitive skills are only part of the changes that are occurring during childhood. Equally crucial is the development of the child’s social skills — the ability to understand, predict, and create bonds with the other people in their environments.

The Continuum of Development (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014) identifies several root social skills that are emerging in children from birth to approximately 3 years of age (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014).

Infants (birth to 24 months of age) show emerging interest in social interactions. For example, they prefer human faces over inanimate objects. They will engage with adults by making eye contact, smiling, and reaching their arms out to indicate they want to be picked up. They begin to imitate adult behaviour and engage in simple pretend play. Older infants and toddlers can play simple games that involve taking turns. As they become more mobile, infants become capable of maintaining a social connection when the adult is not physically close by.

Toddlers (14 months to 3 years) build on the skills that emerged during infancy and start practicing some new skills. They begin to imitate their peers as well as adults. The ability to see a situation from another’s point of view starts to emerge. This enables toddlers to start to engage in parallel play.

Attachment

One of the most important behaviours a child must learn is how to be accepted by others — the development of close and meaningful social relationships.

Attachment is the close emotional bond between a child and the person who provides most of their care, usually a caregiver from which the infant derives a sense of security. The formation of attachments in infancy has been the subject of considerable research as attachments have been viewed as foundations for future relationships. Attachment takes place starting from birth throughout the formative years (infancy and toddlerhood) but can be developed and reinforced at any age. The Canadian Pediatric Society (2018) through the resource ‘Caring for Kids’ describes attachment developing with tasks such as a caregiver’s response to the needs of a baby through daily interactions and routines (daily life events). The more consistent, sensitive, and warm the responses, the stronger the attachment bond.

Additionally, attachments form the basis for confidence and curiosity as toddlers, and as important influences on self-concept.

Harlow’s Research

In one classic study, Wisconsin University psychologists Harry and Margaret Harlow investigated the responses of young rhesus monkeys to explore if breastfeeding was the most important factor to attachment.

Infant monkeys were separated from their biological mothers, and two inanimate surrogate mothers were introduced to their cages. The first inanimate surrogate (the wire mother) consisted of a round wooden head, a mesh of cold metal wires, and a bottle of milk from which the baby monkey could drink. The second Inanimate surrogate was a foam-rubber form wrapped in a heated terry-cloth blanket. The infant monkeys went to the wire “mother” for food, but they overwhelmingly preferred and spent significantly more time with the warm terry-cloth “mother.” The warm terry-cloth “mother” provided no food but did provide comfort (Harlow, 1958, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). The infant’s need for physical closeness and touching is referred to as contact comfort. Contact comfort is believed to be the foundation for attachment. The Harlows’ studies confirmed that babies have social as well as physical needs. Both monkeys and human babies need a secure base that allows them to feel safe. From this base, they can gain the confidence they need to venture out and explore their worlds.

Bowlby’s Theory

Building on the work of Harlow and others, John Bowlby developed the concept of attachment theory. He defined attachment as the affectional bond or tie that an infant forms with the mother. An infant must form this bond with a primary caregiver in order to have normal social and emotional development. In addition, Bowlby proposed that this attachment bond is very powerful and continues throughout life. He used the concept of a secure base to define a healthy attachment between parent and child (Bowlby, 1982, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). A secure base is a parental presence that gives the child a sense of safety as the child explores the surroundings.

Bowlby said that two things are needed for a healthy attachment; the caregiver must be responsive to the child’s physical, social, and emotional needs; and the caregiver and child must engage in mutually enjoyable interactions (Bowlby, 1969, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Additionally, Bowlby observed that infants would go to extraordinary lengths to prevent separation from their caregivers, such as crying, refusing to be comforted, and waiting for the caregiver to return.

Bowlby also observed that these same expressions were common to many other mammals, and consequently argued that these negative responses to separation serve an evolutionary function (Bowlby, 1969, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Because mammalian infants cannot feed or protect themselves, they are dependent upon the care and protection of adults for survival. Thus, those infants who were able to maintain proximity to an attachment figure were more likely to survive and reproduce.

Erikson: Trust versus Mistrust

As previously discussed in our overview of theories, Erik Erikson formulated an eight-stage theory of psychosocial development. Erikson was in agreement on the importance of a secure base, arguing that the most important goal of infancy was the development of a basic sense of trust in one’s caregivers. Consequently, the first stage, trust versus mistrust, highlights the importance of attachment. Erikson maintained that the first year to year and a half of life involves the establishment of a sense of trust (Erikson, 1982, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Infants are dependent and must rely on others to meet their basic physical needs as well as their needs for stimulation and comfort. A caregiver who consistently meets these needs instills a sense of trust or the belief that the world is a trustworthy place. The caregiver should not worry about over indulging a child’s need for comfort, contact or stimulation.

Attachment Relationships in Indigenous Families

Parenting styles in Canada’s Indigenous cultures, First Nations, Metis and Inuit, are similar in some ways and differ in other ways. Values held in common include: a holistic approach to development, balance and respect. The Western view of the caregiver-child attachment relationship tends to focus on the child’s primary caregiver. In Indigenous cultures, a child is connected to his/her immediate family, extended family, community, and ancestors. All of these relationships are seen to be equally important.

the biological function of the attachment relationship is the same across cultures and generations and serves to provide safety, comfort and stress reduction to the infant (Hardy & Bellamy, 2013).

Challenges to Establishing Trust

Erikson (1982, as cited in Paris et al., 2021) believed that mistrust could contaminate all aspects of one’s life and deprive the individual of love and fellowship with others. Consider the implications for establishing trust if a caregiver is unavailable or is upset and ill-prepared to care for a child. Or if a child is born prematurely, is unwanted, or has physical differences that make him or her more challenging to parent. Under these circumstances, we cannot assume that the parent is going to provide the child with a feeling of trust.

The residential school system and the child protection system in Canada have had a profound and long-lasting effect on Indigenous people. Children who were removed from their families and raised in foster care or a residential school have become parents and grandparents. As children, they were subject to abuse, loss and trauma. As a result of this trauma, they are more likely to have difficulty forming healthy attachments as adults (Hardy & Bellamy, 2013).

Mary Ainsworth and the Strange Situation

Developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth, a student of John Bowlby, continued studying the development of attachment in infants. Ainsworth and her colleagues created a laboratory test that measured an infant’s attachment to his or her parent. The test is called The Strange Situation because it is conducted in a context that is unfamiliar to the child and therefore likely to heighten the child’s need for his or her parent (Ainsworth, 1979, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

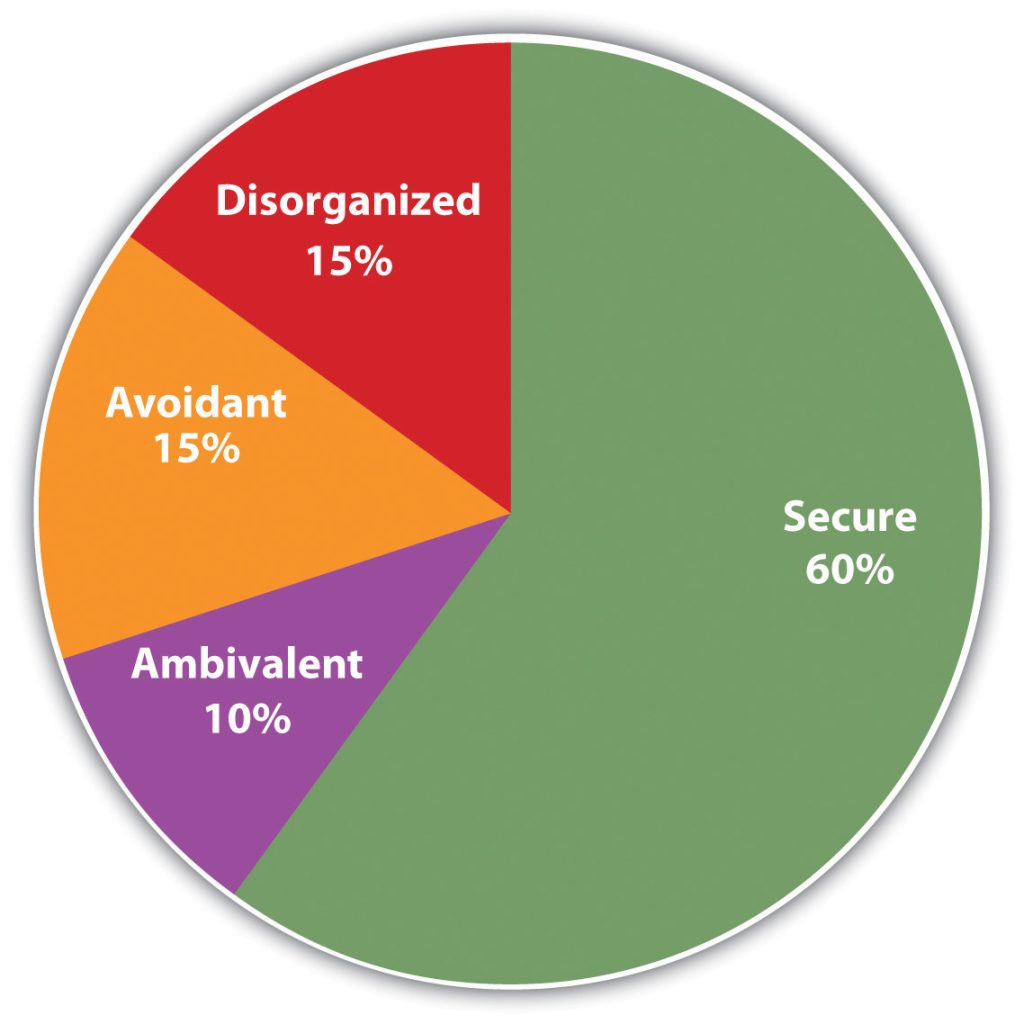

During the procedure, which last about 20 minutes, the parent and the infant are first left alone, while the infant explores the room full of toys. Then a strange adult enters the room and talks for a minute to the parent, after which the parent leaves the room. The stranger stays with the infant for a few minutes, and then the parent again enters and the stranger leaves the room. During the entire session, a video camera records the child’s behaviours. Which are later coded by the research team. The investigators were especially interested in how the child responded to the caregiver leaving and returning to the room, referred to the “reunion.” On the basis of their behaviours, the children are categorized into one of four groups where each group reflect a different kind of attachment relationship with the caregiver. One style is secure and the other three styles are referred to as insecure.

- A child with a secure attachment style usually explores freely while the caregiver is present and may engage with the stranger. The child will typically play with the toys and bring one to the caregiver to show and describe from time to time. The child may be upset when the caregiver departs, but is also happy to see the caregiver return.

- A child with an ambivalent (sometimes called resistant) attachment style is wary about the situation in general, particularly the stranger, and stays close or even clings to the caregiver rather than exploring the toys. When the caregiver leaves, the child is extremely distress and is ambivalent when the caregiver returns. The child may rush to the caregiver, but then fails to be comforted when picked up. The child may still be angry and even resist attempts to be soothed.

- A child with an avoidant attachment style will avoid or ignore the mother, showing little emotion when the mother departs or returns. The child may run away from the mother when she approaches. The child will not explore very much, regardless of who is there, and the stranger will not be treated much differently from the mother.

- A child with a disorganized/disoriented attachment style seems to have an inconsistent way coping with the stress of the strange situation. The child may cry during the separation, but avoid the mother when she returns. Or the child may approach the mother but then freeze or fall to the floor.

Although some cultural differences in attachment styles have been found (Rothbaum, Weisz, Pott, Miyake, & Morelli, 2000 as cited in Walinga & Stagnor, 2014), research has also found that the proportion of children who fall into each of the attachment categories is relatively constant across cultures (see Figure 7.1, “Proportion of Children With Different Attachment Styles”).

You might wonder whether differences in attachment style are determined more by the child (nature) or more by the caregivers (nurture). Most developmental psychologists believe that socialization is primary, arguing that a child becomes securely attached when the mother is available and able to meet the needs of the child in a responsive and appropriate manner, but that the insecure styles occur when the mother is insensitive and responds inconsistently to the child’s needs. In a direct test of this idea, Dutch researcher Dymphna van den Boom (1994) randomly assigned some babies’ mothers to a training session in which they learned to better respond to their children’s needs. The research found that these mothers’ babies were more likely to show a secure attachment style compared with the babies of the mothers in a control group that did not receive training.

But the attachment behaviour of the child is also likely influenced, at least in part, by temperament, the innate personality characteristics of the infant. Some children are warm, friendly, and responsive, whereas others tend to be more irritable, less manageable, and difficult to console. These differences may also play a role in attachment (Gillath, Shaver, Baek, & Chun, 2008; Seifer, Schiller, Sameroff, Resnick, & Riordan, 1996 as cited in Walinga & Stagnor, 2014). Taken together, it seems safe to say that attachment, like most other developmental processes, is affected by an interplay of genetic and socialization influences.

How common are the attachment styles among children? In Canada, attachment disorders are uncommon in the general population (under 1%). That increases to possibly 40% for children who are exposed to gross maltreatment or poor quality institutionalization (Atkinson & Beiser, 2016).

Keep in mind that methods for measuring attachment styles have been based on a model that reflects middle-class, Western values. New methods for assessing attachment styles involve using a Q-sort technique in which a large number of behaviours are recorded on cards and the observer sorts the cards in a way that reflects the type of behaviour that occurs within the situation (Waters, 1987, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). There are 90 items in the third version of the Q-sort technique, and examples of the behaviours assessed include:

- When child returns to mother after playing, the child is sometimes fussy for no clear reason.

- When the child is upset or injured, the child will accept comforting from adults other than mother.

- Child often hugs or cuddles against mother, without her asking or inviting the child to do so.

- When the child is upset by mother’s leaving, the child continues to cry or even gets angry after she is gone.

At least two researchers observe the child and parent in the home for 1.5-2 hours per visit. Usually, two visits are sufficient to gather adequate information. The parent is asked if the behaviours observed are typical for the child. This information is used to test the validity of the Strange Situation classifications across age, cultures, and with clinical populations.

Caregiver interactions and the formation of attachment: Most developmental psychologists argue that a child becomes securely attached when there is consistent contact from one or more caregivers who meet the physical and emotional needs of the child in a responsive and appropriate manner. However, even in cultures where parents do not talk, cuddle, and play with their infants, secure attachments can develop (LeVine et. al., 1994 as cited Walinga & Stangor, 2014).

Attachment styles

The ambivalent style occurs when the parent is insensitive and responds inconsistently to the child’s needs. Consequently, the infant is never sure that the world is a trustworthy place or that they can rely on others without some anxiety. A caregiver who is unavailable, perhaps because of marital tension, substance abuse, or preoccupation with work, may send a message to the infant they cannot rely on having needs met. An infant who receives only sporadic attention when experiencing discomfort may not learn how to calm down. The child may cry if separated from the caregiver and also cry upon their return. They seek constant reassurance that never seems to satisfy their doubt. Keep in mind that clingy behaviour can also just be part of a child’s natural disposition or temperament and does not necessarily reflect some kind of parental neglect. Additionally, a caregiver that attends to a child’s frustration can help teach them to be calm and to relax.

The avoidant style is marked by insecurity, but this style is also characterized by a tendency to avoid contact with the caregiver and with others. This child may have learned that needs typically go unmet and learns that the caregiver does not provide care and cannot be relied upon for comfort, even sporadically. An insecure avoidant child learns to be more independent and disengaged.

The disorganized/disoriented style represents the most insecure style of attachment and occurs when the child is given mixed, confused, and inappropriate responses from the caregiver. For example, a parent who suffers from schizophrenia may laugh when a child is hurting or cry when a child exhibits joy. The child does not learn how to interpret emotions or to connect with the unpredictable parent. This type of attachment is also often seen in children who have been abused. Research has shown that abuse disrupts a child’s ability to regulate their emotions (Main and Solomon, 1990).

Caregiver Consistency

Having a consistent caregiver may be jeopardized if the infant is cared for in a child care setting with a high turnover of staff or if institutionalized and given little more than basic physical care.

Infants who, perhaps because of being in orphanages with inadequate care, have not had the opportunity to attach in infancy may still form initial secure attachments several years later. However, they may be more likely to experience depression and anger or be overly friendly as they interact with others (O’Connor et. al., 2003, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

Social Deprivation

Severe deprivation of parental attachment can have serious consequences for development across developmental domains. According to studies of children who have not been given warm, nurturing care, they may show developmental delays, failure to thrive and attachment disorders (Bowlby, 1982, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Non-organic failure to thrive is the diagnosis for an infant who does not grow, develop, or gain weight on schedule. In addition, postpartum depression can cause even a well-intentioned mother to neglect her infant.

Reactive Attachment Disorder

Children who experience social neglect or deprivation, repeatedly change primary caregivers that limit opportunities to form stable attachments, or are reared in unusual settings (such as institutions) that limit opportunities to form stable attachments can certainly have difficulty form attachments. According to the Diagnostic and Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) those children experiencing neglectful situations and also displaying markedly disturbed and developmentally inappropriate attachment behaviour, such as being inhibited and withdrawn, minimal social and emotional responsiveness to others, and limited positive affect, may be diagnosed with Reactive Attachment Disorder. This disorder often occurs with developmental delays, especially in cognitive and language areas. Fortunately, the majority of severely neglected children do not develop Reactive Attachment Disorder, which occurs in less than 10% of such children. The quality of the caregiving environment after serious neglect affects the development of this disorder.

Resiliency

Being able to overcome challenges and successfully adapt is resiliency. Even young children can exhibit strong resilience to harsh circumstances. Resiliency can be attributed to certain personality factors, such as an easy-going temperament. Some children are warm, friendly, and responsive, whereas others tend to be more irritable, less manageable, and difficult to console, and these differences play a role in attachment (Gillath, Shaver, Baek, & Chun, 2008; Seifer, Schiller, Sameroff, Resnich, & Riordan, 1996, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). It seems safe to say that attachment, like most other developmental processes, is affected by an inter play of genetic and socialization influences.

Receiving support from others also leads to resiliency. A positive and strong support group can help a parent and child build a strong foundation by offering assistance and positive attitudes toward the newborn and parent. In a direct test of this idea, Dutch researcher van den Boom (1994, as cited in Paris et al., 2021) randomly assigned some babies/mothers to a training session in which they learned to better respond to their children’s needs. The research found that these mothers’ babies were more likely to show a secure attachment style in comparison the other mothers in a control group that did not receive training (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Cultural Variations

The term culture refers to all of the beliefs, customs, ideas, behaviours, and traditions of a particular society that are passed through generations. Culture is transmitted to people through language as well as through the modeling of behaviour, and it defines which traits and behaviours are considered important, desirable, or undesirable.

Some cultural differences in attachment styles have been found (Rothbaum, Weisz, Pott, Miyake, & Morelli, 2010, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). For example, German parents value independence and Japanese mothers are typically by their children’s sides. As a result, the rate of insecure-avoidant attachments is higher in Germany and insecure-resistant attachments are higher in Japan. These differences reflect cultural variation rather than true insecurity (Van Ijzendoorn and Sagi, 1999, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

A research study of development among Indigenous children in Canada, conducted by Findlay, Kohen and Miller (2014), concluded that the age range for the development of certain skills, including social skills, can be different for Indigenous children compared to the general population. For example, the cultural norm in some Indigenous identity groups of living with extended family members may influence the development of certain social skills by providing additional support and modelling behaviour. The study also found variations between Indigenous identity groups (Metis, Inuit and off-reserve First Nations) in expectations for children to develop independent behaviours. The researchers emphasized the importance of using culturally specific age ranges and interventions because using those based on the general population might result in over or under identification of children at risk for developmental delays. (Findlay, Kohen, & Miller, 2014).

Summary

- How emotions develop.

- The expression and regulation of emotions.

- The stages of play and their importance.

- The role of attachment at this stage.

References

Canadian Pediatric Society. (2018). Attachment: A connection for life. https://caringforkids.cps.ca/handouts/pregnancy-and-babies/attachment

Lally, M. & Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan development: A psychological perspective (2nd ed.). http://dept.clcillinois.edu/psy/LifespanDevelopment.pdf

Paris, J., Ricardo, A., Rymond, A., & Johnson, A. (2021). Child Growth and Development. https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Early_Childhood_Education/Book%3A_Child_Growth_and_Development

Pye, T., Scoffin, S., Quade, J., & Krieg, J. (2022). Child Growth and Development Canadian Ed. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/childgrowthanddevelopment/

Atkinson, L. & Beiser, M. (Eds.). (2016). Attachment disorders. In caring for kids new to Canada. Retrieved from https://kidsnewtocanada.ca/mental-health/attachment-disorders

Findlay, L., Kohen, D., & Miller, A. (2014). Developmental milestones among Aboriginal children in Canada. Paediatrics & child health, 19(5), 241–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/19.5.241.

Hardy, C. & Bellamy, S. (Eds). Caregiver-infant attachement for aborigional families. https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/health/FS-InfantAttachment-Hardy-Bellamy-EN.pdf

Lally, M. & Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan development: A psychological perspective (2nd ed.). http://dept.clcillinois.edu/psy/LifespanDevelopment.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). Excerpts from “Elect”. https://www.dufferincounty.ca/sites/default/files/rtb/Excerpts-from-Early-Learning-for-Every-Child-Today.pdf

Shanker, S. (2013). Calm, alert and happy. Retrieved from https://www.totallyawake4-life.com/Self%20Regulation%20Artcile%20Shanker.pdf

Walinga, J., & Stangor, C. (2014). Introduction to Psychology – 1st Canadian edition. https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontopsychology/

OER Attributions

Child Growth and Development Canadian Ed (2022) by Tanya Pye; Susan Scoffin; Janice Quade; and Jane Krieg is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Child Growth and Development by Paris, Ricardo, Rymond, and Johnson is shared under a CC BY license, except where otherwise noted.

Introduction to Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition Copyright © 2014 by Jennifer Walinga and Charles Stangor is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Lifespan Development by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 except where otherwise noted.