Child Development: Theories and Themes

Learning Objectives

After this reading, you will be able to:

- List the major theories of child development

- Describe the different forms of attachment

- Define Ecological Systems Theory

Introduction

This Open Education Resource (OER) has been developed for students in the Child Development course for the Centennial College Child and Youth Care program.

Think about how you were five, ten, or even fifteen years ago. In what ways have you changed? In what ways have you remained the same? You have probably changed physically; perhaps you’ve grown taller or your hair has changed. You may have also experienced changes in the way you think and solve problems, and how you connect with others. This is development: The study of changes over time.

Much of the information available regarding child development can be very… Early Childhood Educator (ECE) forward. Which is great for an ECE, we love that! However, for a Child and Youth Care Practitioner (CYCP) student, it can be challenging to find information that is relevant specifically to our field. So I have edited the content for the readings in this course from multiple OER sources to provide you with current and relevant information, with a CYCP lens. We will follow guidelines and standards of practice specifically for CYCPs, including:

- Competencies for Professional Child & Youth Work Practitioners (ACYCP, 2010).

- Standards for Practice of North American Child & Youth Care Professionals (ACYCP, 2017)

- Ontario Association of Child and Youth Care Code of Ethics (OACYC, 2017)

You will become familiar with these standards and guidelines throughout the program, but these documents inform our work throughout our careers, from being a student to being a seasoned practitioner in the field.

Understanding the patterns of development provide the ability for professionals such as CYCPs to build caring and responsive relationships (OACYC, 2021), design safe and accessible environments which support children’s play and learning, both of which contribute to a sense of belonging and overall well-being (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014).

This reading will provide an overview of the major themes and theories about child development, which we will explore throughout the course. Think of this week’s reading as a teaser trailer for what we’ll learn throughout the course!

What is child development?

To understand the area known as child development, first we need to understand how society’s views of children and childhood have unfolded.

French historian Philippe Ariès published a book titled “L’enfant et la vie familiale sous l’ancien régime” later translated into English as “Centuries of Childhood” in 1960.

In the book, he discusses how the concept of childhood was created by modern society. Attitudes towards children have evolved over time along with economic change and social advancement. Before the 17th century, children were generally considered weaker, more insignificant versions of adults. They were were assumed to be subject to the same needs and desires as adults, and to have the same vices and virtues as adults. Therefore they dressed the same, were not warranted more privileges, and they worked the same hours and received the same punishments for misdeeds. Children were considered adults as soon as they could live alone.

At the time, this was how society viewed and understood lifespan development. The only difference between children and adults was size. We now have learned that this view is incomplete and outdated, but how do we come up with (or formulate) modern-day theories?

Our own personal theories about development are based on experiences, folklore, stories in the media, or built haphazardly on unverified observation. However, theories presented in this course are more formal. They are based on prior findings and observations by psychologists and other researchers, and provide a framework through which we can draw conclusions and make predictions about human behaviour.

These theories are subject to rigorous testing though research. In this week’s reading, we’ll review the major theoretical perspectives and theories that pertain to lifespan development. Each perspective emphasizes a different aspect of development and is just one means of studying the ever-evolving discipline of childhood development.

What aspects of ourselves change and develop as we journey through life? We move through significant physical, cognitive, and psychosocial changes throughout our lives—do these changes happen in a systematic way, and to everyone? How much is due to genetics and how much is due to environmental influences and experiences (both within our personal control and beyond)? Is there just one course of development or are there many different courses of development? In this module, we’ll examine these questions and learn about the major stages of development and what kind of developmental tasks and transitions we might expect along the way.

Child development is a multidisciplinary field that explores how individuals grow, learn, and change from conception through adolescence. There are several major theories that have shaped the understanding of child development, which we will explore throughout the course.

Themes in child development

There are several underlying principles of development to keep in mind:

- Development is lifelong and change is apparent across the lifespan (although this text ends with adolescence). Early experiences affect later development

- Development is multidirectional. We show gains in some areas of development while showing a loss in other areas

- Development is multidimensional. We change across three general domains/dimensions: physical, cognitive, and social-emotional

The physical domain includes changes in height and weight, changes in gross and fine motor skills, the senses, the nervous system, as well as health and wellness.

The cognitive domain encompasses learning, attention, memory, language, thinking, reasoning, and creativity.

The social and emotional domain (also referred to as psychosocial) focuses on changes in emotion, personality, self-perception, and interpersonal relationships with families, peers, and friends.

These domains influence each other, meaning that a change in one domain may result in changes to one or more of the other domains.

Development is characterized by plasticity, which is our ability to change, and that many of our characteristics are malleable. Early experiences are important, but children are remarkably resilient (able to overcome adversity).

Development is multi-contextual (Lally & Valentine-French, 2023). We are influenced by both nature (genetics) and nurture (the environment) – when and where we live and our actions, beliefs, and values are a response to circumstances surrounding us. The key here is to understand that behaviours, motivations, emotions, and choices are all part of a bigger picture (Lumen Learning, n.d.).

Next, lets look at the periods (stages or ages) of development we will focus on throughout the course.

Think It Over

Within the field of Child and Youth Care (CYC), there is a lot of information that we must consider to best support healthy development for children and youth. Regardless of the setting we are working in, development is a main focus. It provides benchmarks that we can compare and contrast a young person’s strengths, developments, and potentials for growth, relationships, and connection.

Children do not grow in a vacuum. Their environment, the people around them, their communities, everything influences development. The more understanding we have about development, general milestones (or goals) and what we can expect, we can better adapt our approach when working with children and youth.

Periods of development

Consider what periods of development you think a course on development would address. How many stages are on your list? Infancy and childhood, and teenagers.

Developmentalists (those that study development) break this part of the life span into these stages as follows:

- Prenatal development (conception through birth)

- Infancy and toddlerhood (birth through 2 years)

- Early childhood (preschool years, 3 to 5)

- Middle childhood (6 to 12 years)

- Adolescence (13 to 18 years)

- Emerging adulthood (18 to 29 years)

- Adulthood (30+ years)

We will discuss this further in next week’s content, but the scope of practice of a CYC practitioner is children, youth and families in a variety of settings. For the purpose of this course, we will focus on development from conception to age 11, or middle childhood.

Content for our course will be divided by stages, and by the domains in the previous section (or areas of development). This is an overview of each stage:

Prenatal development

Conception occurs and development begins. All of the major structures of the body are forming and the health of the mother is of primary concern. Understanding nutrition, teratogens (or environmental factors that can lead to birth defects), and labor and delivery are primary concerns.

Infancy and toddlerhood

The first two years of life are ones of dramatic growth and change. A newborn, with a keen sense of hearing but very poor vision is transformed into a walking, talking toddler within a relatively short period of time. Caregivers are also transformed from someone who manages the feeding and sleep schedules to a constantly moving guide and safety inspector for a mobile, energetic child.

Early childhood

Early childhood is also referred to as the preschool years and consists of the years which follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling (grade 1). As a three to five-year-old, the child is busy learning a language, is gaining a sense of self and greater independence and is beginning to learn the workings of the physical world. This knowledge does not come quickly, however, and preschoolers may initially have interesting conceptions of size, time, space, and distance such as fearing that they may go down the drain if they sit at the front of the bathtub or by demonstrating how long something will take by holding out their two index fingers several inches apart. A toddler’s fierce determination to do something may give way to a four-year-old’s sense of guilt for action that brings the disapproval of others.

Middle childhood

The ages of six through twelve comprise middle childhood and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school. Now the world becomes one of learning and testing new academic skills and of assessing one’s abilities and accomplishments by making comparisons between self and others. Schools compare students and make these comparisons public through team sports, test scores, and other forms of recognition. Growth rates slow down and children are able to refine their motor skills at this point in life. Children begin to learn about social relationships beyond the family through interaction with friends and fellow students.

Let’s explore what theories are and introduce you to some major theories in child development.

Issues in Development

There are some aspects of development that have been hotly debated throughout history, and some continue today. Three key issues remain among which developmental theorists often disagree:

- Nature vs. nurture – the influence of heredity or the environment

- Continuity vs. discontinuity – is development a slow and gradual process, or quick and abrupt?

- Active vs. passive – does an individual (and their caregivers) play an active role in their own development? Or is it due to genetics and the environment?

The role of early experiences on later development in opposition to current behaviour reflecting present experiences–namely the passive versus active issue. Likewise, whether or not development is best viewed as occurring in stages or rather as a gradual and cumulative process of change has traditionally been up for debate – a question of continuity versus discontinuity. Further, the role of heredity and the environment in shaping human development is a much-contested topic of discussion – also referred to as the nature/nurture debate.

Developmental theories

What is a theory?

In our attempts to make sense of the world and our human experience, it is in our nature to ask questions and develop theories, both formal and informal. This begins at an early age and as we move through this course, we will explore examples of children developing and testing their theories.

Have you ever wondered, “Why is my 3 year-old so inquisitive?” or “Why are some fifth graders better able to make friends?”

A theory is an organized way to make sense of information, and can help to make predictions and explain these and other occurrences. Theories can be further tested through research. Developmental theories offer explanations about how we develop, why we change over time, and the kinds of influences that impact development.

A theory also guides how information is collected, interpreted, and applied to real-life situations. It provides the researcher with a blueprint or model to be used to help piece together various studies. Think of theories as frameworks or guidelines much like directions that come with an appliance or other object that requires assembly. The instructions can help one piece together smaller parts more easily than if trial and error are used.

A theory gives us a framework and a logic for our practices. Theories help us to organize the knowledge we have, and they help us to make predictions about what might occur in the future.

A hypothesis is a testable prediction about how the world will behave if our idea is correct, and it is often worded as an if-then statement (e.g., if I complete my weekly readings and prepare for class, I will do well in my assignments). The hypothesis is critical because it bridges the gap between the realm of ideas and the real world.

As specific hypotheses are tested, theories are modified and refined to reflect and incorporate the result of these tests.

The understanding of a theory enables us to consider the ways children are exposed to and interact with their environment, and the people around them. Professionals such as CYCPs, educators, and others apply this knowledge to support healthy development. Practitioners consider what the children already know, the concepts they are learning or developing, and the concepts children would benefit from developing. These practices are based on broader behaviours, skills, and concepts that explain why and how children grow and develop. It is not enough to merely provide experiences for children, we should have a rationale for why we engage them in certain practices.

History of research in child development

The scientific study of children began in the late nineteenth century and blossomed in the early twentieth century as pioneering psychologists sought to uncover the secrets of human behaviour by studying its development. Early scholars John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Charles Darwin proposed theories of human behaviour that are the “direct ancestors of some major theoretical traditions” of developmental psychology today (Vasta et al., 1998, p. 10 as cited in Lumen Learning, n.d.).

Locke, a British empiricist, adhered to a strict environmentalist position. He saw the newborn’s mind as a tabula rasa or “blank slate” on which knowledge is written through experience and learning.

Rousseau, a Swiss philosopher who spent much of his life in France, proposed a nativistic model in his famous novel Emile, in which development occurs according to innate processes progressing through three stages: Infans (infancy), puer (childhood), and adolescence. Rousseau detailed some of the necessary progression through these stages in order to develop into an ideal citizen. Although some aspects of his text were controversial, Rousseau’s ideas were strongly influential on educators at the time.

Finally, the work of Darwin, the British biologist famous for his theory of evolution (National Geographic, 2022), led others to suggest that development proceeds through evolutionary recapitulation, with many human behaviour having their origins in successful adaptations in the past.

Who studies development and why?

Many academic disciplines contribute to the study of development and this type is offered in some schools as psychology (particularly as developmental psychology); in other schools, it is taught under sociology, human development, or family studies. This multidisciplinary course is made up of contributions from researchers in the areas of health care, anthropology, nutrition, child development, biology, gerontology, psychology, and sociology, among others. Consequently, the stories provided are rich and well-rounded and the theories and findings can be part of a collaborative effort to understand human lives.

The main goals of those involved in studying human development are to describe and explain changes. Throughout this course, we will describe general observations during childhood development, then examine how theories provide explanations for why these changes occur. For example, you may observe two-year-old children be particularly temperamental, and researchers offer theories to explain why that is.

Theories are not facts; they are guidelines for investigation and practice, and they gain credibility through research that fails to disprove them (Lumen Learning, n.d.).

Academics and researchers have, and do, develop theories and frameworks for thinking critically about human knowledge and systems. Critical theory is an example of a postmodern theory the aim of which is to unmask the ideology that falsely justifies some form of economic or social oppression and to see it for what it is…ideology! This can set in motion the task of ending the oppression.

In child development, we rely on a systematic approach to understanding behaviour, based on observable events and scientific methods. These are carried out using observation, experiments, case studies, and surveys, and can be conducted through research that can be longitudinal, cross-sectional, or sequential.

There are so many different observations about childhood, adulthood, and development in general that we use theories to help organize all of the different observable events or variables. A theory is a simplified explanation of the world that attempts to explain how variables interact with each other. It can take complex, interconnected issues and narrow them down to the essentials. This enables developmental theorists and researchers to analyze the problem in greater depth.

Challenging historical views and theories

Today many nations are actively addressing the legacies of colonialism that brought with it such things as patriarchy, eurocentrism, and structuralism. It has been feminist theory, queer theory, Black, Indigenous, people of colour (BIPOC), and other marginalized groups who, over the past few years, have helped to draw attention to, and disrupt, what, in socio-cultural terms are often referred to as dominant discourses and grand narratives. These ways of describing the world and human experience tend to align with a Western ideology with embedded hierarchies and colonist world views. Historically, these narratives have served to advantage certain populations while pathologizing and further marginalizing others. The process of re-conceptualizing is embraced as a way to move forward with social justice.

Critical theory outlines that we adopt a postmodern perspective of child development and encourages early educators to re-examine ideologies, beliefs, and assumptions and to question and look beyond the fixed views of children proposed by existing theories. In everyday practice, this may look like critically examining a storybook for any hidden political or social points of view ( e.g., gender, race, class, etc.) made through the stories and images. Posing questions such as whose story is this? Who gets to tell the story? Is it a true representation? Who has been left out? Educators are encouraged to engage in conversations with families and children about representations.

In sum, the postmodern perspective encourages multiple perspectives of viewing how children develop and learn, instead of one subjective view of child development.

Within the dominant discourse described above, the scientific method was lauded as the way to objectively quantify and describe the world, including human development and diversity. We are re-conceptualizing science as one of many ways to describe and make meaning of the world and human experience. We are only here today because our ancestors survived and flourished for millennia. They shared their experiences across generations through oral tradition and art as examples.

Indigenous Perspectives

In Indigenous cultures, children are viewed as sacred gifts from the Creator and therefore their growth is seen as a spiritual journey of development and learning. The Medicine Wheel that symbolizes stages of life is used to represent this sacred journey. First Nation, Inuit, and Métis families are interdependent and with each stage of life, each member brings special gifts as well as responsibilities to the family and community. Knowledge Keepers bring teachings from ancestors to help children understand their sacred place in the universe.

Indigenous communities view child development as a journey that is closely bound by the natural and spiritual world and therefore the developing child is shaped by unique ways of knowing and teachings.

We are now beginning to incorporate how these ways of living in the world have been a part of our history for thousands of years, thinking critically about the western views history and past research have been based on, and expanding on them to be more inclusive. One way to begin to integrate these world views is through ‘Two-Eyed Seeing.’ This guiding principle refers to learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledges and ways of knowing … and learning to use both these eyes together, for the benefit of all. Shared by Elder Albert Marshall in 2004 ‘Two-Eyed Seeing’ is the gift of multiple perspective treasured by many Indigenous peoples (Institute for Integrative Science and Health, n.d.), and refers to shifting from the Western binary dualism of ‘either/or’ to embracing the positive in both of these world views as ‘both/and.’

Please note that the above is not a critique of science. We do not have to look too far to see evidence of just how much science has contributed to global human health and well-being. It is about HOW we can move beyond only science to embrace human diversity.

There are so many theories relating to development. We could easily spend an entire 14 weeks on each theory! Unfortunately, we only have 14 weeks to review development in general.

The following list provides some of the most important theories we’ll cover each week, organized by area (domain) of development. It is very brief, and we will touch on the majority of these theories.

Let’s briefly outline some of the major theories we’ll cover throughout the course.

Key theories in child development

Some theories focus on the skills reflected by children as they engage with the world and move through developmental stages (constructivist theories). Some theories focus strictly on behaviour and how it develops (behaviourism). There are theories that focus on the broader context of the child (ecological/contextual theories), and some focus on the child’s construction of knowledge while also focusing on the immediate surroundings (sociocultural/cooperative theories).

Using theory as a framework builds our scientific understanding of how children grow and develop. Other theories look at relationships, attachment, and connection with a child and their caregiver.

Constructivist Theories

Cognitive Developmental Theory

Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory is a form of constructivism. According to cognitive developmental theory, children construct their own learning through interactions and experiences in the environment. Piaget (1962, as cited in Pegorraro Schull et al., 2021) argued that we are constantly organizing our world by categorizing information and determining ways of applying this information.

Psychosexual theory, and the theory of the self

This reading includes Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), who has been a very influential yet controversial figure in the field of developmental psychology, however; the scope of this course is limited, and we will only briefly mention Freud throughout.

Freud’s view of development and psychopathology dominated the field of psychiatry until the growth of behaviourism in the 1950s.

He viewed development as discontinuous, and believed that each of us must pass through a series of stages during childhood. If we lack proper nurturance and caregiving during a stage (such as if a caregiver is either overly punitive or lax) we may become stuck, or fixated, in that stage and not progress to the next one. Freud’s stages are called the stages of psychosexual development.

According to Freud, children’s pleasure-seeking urges are focused on a different area of the body, called an erogenous zone, at each of the five stages of development: oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital. Connecting to these stages, Freud’s theory of self suggests that there are three parts of the self: The id, the ego, and the superego. Personality is thought to develop in response to the child’s ability to learn to manage biological urges.

Freud’s assumptions about what can influence the formation of personality during the first few years of life, and that the ways that interactions between children and their caregivers have a long-lasting impact on children’s emotional states, have guided caregivers, educators, clinicians, and policy makers for many years.

Main points to note about Freud’s theories

- Biological urges, from the time a baby is born, progress through stages that a child must pass through, and if something impedes that, the child remains in that stage.

We have only recently begun to recognize that early childhood experiences do not always result in certain personality traits or emotional states.

Psychosocial Theory

Erik Erikson (1902-1994) suggested that our relationships and society’s expectations motivate much of our behaviour in his theory of psychosocial development. He is considered the father of developmental psychology because his model has given us a guideline for the entire life span, and suggests certain primary psychological and social concerns throughout life.

Erikson was a student of Sigmund Freud but emphasized the importance of the ego, or conscious thought, in determining our actions. In other words, he believed that we are not driven by unconscious urges. We know what motivates us and we consciously think about how to achieve our goals. Erikson expanded on Freud’s theories by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations, and adding three stages of adult development (Erikson, 1950; 1968, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Rymond, & Johnson, 2020).

Behaviourism

Ivan Pavlov

Ivan Pavlov (1880-1937) was a Russian physiologist interested in studying digestion. As he recorded the amount of salivation his laboratory dogs produced as they ate, he noticed that they actually began to salivate before the food arrived as the researcher walked down the hall and toward the cage. The dogs knew that the food was coming because they had learned to associate the footsteps with the food. The keyword here is “learned”. A learned response is called a “conditioned” response.

John B. Watson

B.F. Skinner

Social Learning Theory

Ecological/Contextual Theories

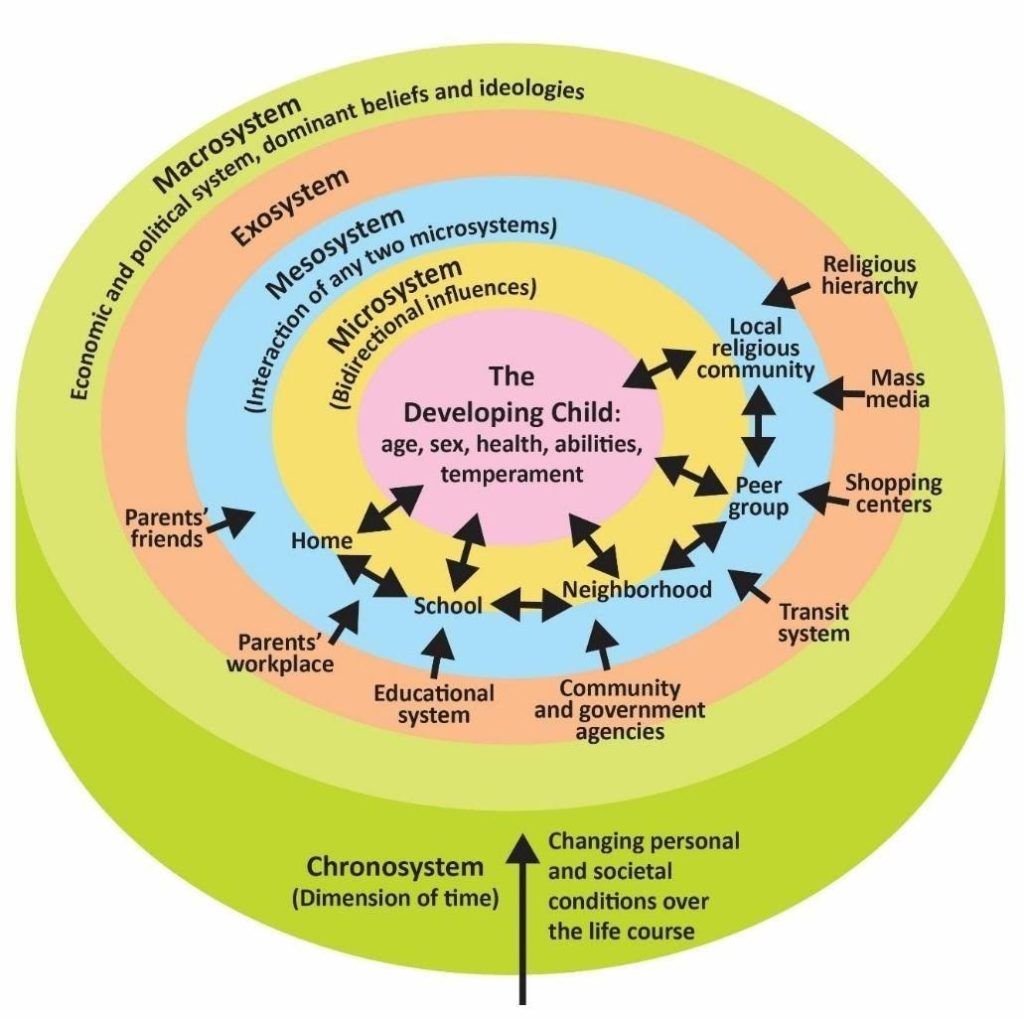

Ecological theories emphasize the child’s system and context. Ecological theories of human development focus on the interrelationships between broader environmental systems and their impact on a child’s development. In contrast to the theoretical approaches presented earlier in the chapter, ecological theories look more broadly at the complex levels of the child’s environment and how this impacts learning. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory examines the social resources and relationships that directly and indirectly impact a child’s development. Bronfenbrenner focuses on multiple environments of the child, including the contexts of home, neighborhood, community, and culture (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Friere’s critical literacy theory focuses on understanding the social, cultural, and political contexts of learners (Friere, 1985). These theories take an ecological approach as they are focused on understanding the child in the backdrop of time, place, and circumstance.

Ecological Systems Theory

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005) offers us one of the most comprehensive theories of human development. Bronfenbrenner studied Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and learning theorists and believed that all of those theories could be enhanced by adding the dimension of context. What is being taught and how society interprets situations depends on who is involved in the life of a child and on when and where a child lives.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory explains the direct and indirect influences on an individual’s development, and challenges us to go beyond the individual if we want to understand human development and promote improvements (Leon, n.d. as cited in Lally & Valentine-French, 2023).

“Ecological theory, in particular the pioneering work of Urie Bronfenbrenner, has been influential in the field of Child and Youth Care. Ecological theory not only has deep and far-reaching roots in the field, but also has the potential to influence new directions and development in Child and Youth Care” (Derksen, 2010 p. 326.)

The ecological theory of human development emphasizes the contextual interrelationships that exist between individuals, families, the physical environment, the community, and the cultural norms and values of a society. Each of these relationships exerts contextual influence on the individual and is depicted by concentric circles embedded within one another. The nested spheres of influence are represented in the graphic “Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems” (see image below) and include the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and the macrosystem, with each system based on a greater understanding of influence (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

Indigenous Perspectives

As for Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model, it seems the same as the saying: It takes a community to raise a child. In some Indigenous communities, the aunts and uncles are the ones who “discipline” children to keep harmony in the family. Discipline in the sense that they talk to the children when they are not contributing to the household or when they are giving their parents a hard time. It is common for children to go live with either aunts and uncles, or grandparents for periods of time to learn different skills, knowledge and/or teachings as well as to go help out with child-rearing. There is a strong sense of sharing our gifts from the Creator, the children, with our extended family. They are considered to be lent to us by the Creator.

Sociocultural Theories

Sociocultural theories bridge the gap between constructivist approaches and ecological approaches by emphasizing cooperation. These theories emphasize the immediate environment and include a practitioner’s analysis of children’s observable skills and behaviours to present children with the next valuable learning moment. Children develop language skills individually, but they do so within a cooperative learning context as peers, family members, teachers, and others engage, support, and teach them. Vygotsky’s sociocultural learning theory is notable for focusing on what the child can do, while also suggesting that a child’s learning is supported when the right amount of instruction is provided at the right time. Marie Clay’s theories and definitions of emergent reading provide us with a framework for understanding individual children’s prior knowledge and readiness for different literacy experiences. These theories focus on the interactive nature of the child’s capabilities, experiences, and interactions with others.

Sociocultural Learning Theory

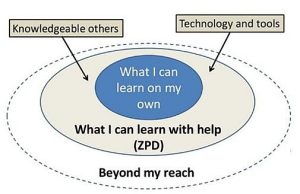

Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) was a Russian psychologist who wrote in the early 1900s but whose work was discovered in the United States in the 1960s but became more widely known in the 1980s. Vygotsky differed with Piaget in that he believed that a person not only has a set of abilities, but also a set of potential abilities that can be realized if given the proper guidance from others. His sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and interaction in the development of cognitive abilities. He believed that through guided participation known as scaffolding, with a teacher or capable peer, a child can learn cognitive skills within a certain range known as the zone of proximal development (ZPD; Lumen Learning, n.d.). His belief was that development occurred first through children’s immediate social interactions, and then moved to the individual level as they began to internalize their learning (Leon, n.d. as cited in Lumen Learning, n.d.).

Vygotsky’s sociocultural learning theory emphasizes the social aspect of children constructing their learning (1986). Vygotsky believed that cognitive growth was a result of interactions between people, after which a child internalizes learning. According to this theory, children learn most effectively by engaging meaningfully with someone who is more experienced. Vygotsky developed the concept of the zone of proximal development. He defines it as “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by the independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving” (Vygotsky, 1978, p86 as cited in Lumen Learning, n.d.).

Vygotsky stated that learners should be taught in the ZPD. A good teacher, CYCP, or more-knowledgable-other (MKO) identifies a learner’s ZPD and helps them stretch beyond it. Then the MKO gradually withdraws support until the learner can perform the task unaided. Other psychologists have applied the metaphor of scaffolds (the temporary platforms on which construction workers stand) to Vygotsky’s theory. Scaffolding is the temporary support that a MKO gives a learner to do a task. Vygotsky recognized a more knowledgeable other could be another child, a family member, a teacher, or anyone who can provide some support for a task. The support itself is called scaffolding. Construction workers, painters, and others use physical scaffolds when they work to reach areas beyond their abilities if merely standing on the ground. In this same way, the support of a more experienced peer giving guidance or direction creates a support for the child to be able to construct their own learning. As a child masters a task, they need less scaffolding and eventually the scaffold disappears (Vygotsky, 1978).

For example, many young children have help in learning to wash their hands. A CYCP may show the child how to acquire the soap, rub their hands vigorously, and rinse. Over time, children need less help with the task, and the scaffold is removed as children are able to wash their hands independently. Children are in progressive zones of proximal development when they are still needing some guidance to wash their hands. Vygotsky placed great importance on the social experience, which provides the scaffold. This theory allows for the notion that children construct their learning, but it also emphasizes that construction requires some help from others.

Relationships

Attachment

Attachment is the close bond with a caregiver from which the infant derives a sense of security. The formation of attachments in infancy has been the subject of considerable research as attachments have been viewed as foundations for future relationships. Additionally, attachments form the basis for confidence and curiosity as toddlers, and as important influences on self-concept. A secure base, or secure attachment, is a sign of a healthy relationship.

Many researchers have explored attachment in different ways. In one classic study, Wisconsin University psychologists Harry and Margaret Harlow investigated the responses of young rhesus monkeys to explore if breastfeeding was the most important factor to attachment.

Infant monkeys were separated from their biological mothers, and two inanimate surrogate mothers were introduced to their cages. The first inanimate surrogate (the wire mother) consisted of a round wooden head, a mesh of cold metal wires, and a bottle of milk from which the baby monkey could drink. The second inanimate surrogate was a foam-rubber form wrapped in a heated terrycloth blanket. The infant monkeys went to the wire “mother” for food, but they overwhelmingly preferred and spent significantly more time with the warm terrycloth “mother.” The warm terry-cloth surrogate provided no food but did provide comfort (Harlow, 1958, as cited in Paris, et al., 2020).

Building on the work of Harlow and others, John Bowlby developed the concept of attachment theory. He developed the definition for attachment, describing it as the affectional bond or tie that an infant forms with the mother. An infant must form this bond with a primary caregiver in order to have normal social and emotional development. In addition, Bowlby proposed that this attachment bond is very powerful and continues throughout life. He used the concept of a secure base to define a healthy attachment between parent and child (Bowlby, 1982, as cited in Paris, et al., 2020). A secure base is a parental presence that gives the child a sense of safety as the child explores the surroundings.

Developmental psychologist Dr. Mary Ainsworth, a student of John Bowlby, continued studying the development of attachment in infants at the University of Toronto. Dr. Ainsworth and her colleagues created a laboratory test that measured an infant’s attachment to their caregiver. The test is called The Strange Situation because it is conducted in a context that is unfamiliar to the infant and therefore likely to heighten the need for their parent (Ainsworth, 1979, as cited in Paris, et al., 2020). From these interactions and how an infant reacted, patterns of attachment relationships could be determined.

Sensitive caregiving in the early years plays a key role in the emergence of secure attachments. For example, caregiver support, acceptance of the child and sensitive behaviours during joint play foster a secure attachment. In contrast, domestic violence, frightening, insensitive or neglectful caregiving or maltreatment are important predictors in the development of attachment insecurity and disorganization. Changes in parental acceptance or disruption of the family can alter attachment pathways in either direction, temporarily or permanently.

How common are the attachment styles among children? In Canada, attachment disorders are uncommon in the general population (under 1%). That increases to possibly 40% for children who are exposed to gross maltreatment or poor quality institutionalization (Atkinson & Beiser, 2016).

Keep in mind that methods for measuring attachment styles have been based on a model that reflects middle-class, Western values.

Attachment Relationships across cultures

The Western view of the caregiver-child attachment relationship tends to focus on the child’s primary caregiver. Hardy and Bellamy (2013) describe that “attachment is not about parenting styles, values, or even about different parenting behaviours. Attachment behaviours may look different across different cultures but they achieve the same function” (p. 2) and that “all cultures change and evolve over time and parenting practices within each culture also change slightly” (p. 2) between generations.

Some cultural differences in attachment styles have been found (Rothbaum, Weisz, Pott, Miyake, & Morelli, 2010, as cited in Paris, et al., 2020). For example, German parents value independence and Japanese mothers are typically by their children’s sides.

By using this westernized attachment rating, as a result, the rate of insecure-avoidant attachments is higher in Germany and insecure-resistant attachments are higher in Japan. These differences reflect cultural variation rather than true insecurity (Van Ijzendoorn and Sagi, 1999, as cited in Paris, et al., 2020).

Parenting styles in many of Canada’s Indigenous cultures, First Nations, Métis and Inuit, are similar in some ways to western cultures, and differ in other ways. Values held in common include: a holistic approach to development, balance and respect.

In Indigenous cultures, a child is connected to their immediate family, extended family, community, and ancestors. All of these relationships are seen to be equally important.

A research study of development among Indigenous children in Canada, conducted by Findlay, Kohen and Miller (2014), concluded that the age range for the development of certain skills, including social skills, can be different for Indigenous children compared to the children raised in Western culture.

👉To learn more about attachment, check out this resource from SickKids: Different types of attachment

Canada’s Contribution to Child Development Research

Canada has a long history of contributing to child development research!

- In 1892, James Mark Baldwin was appointed the first social scientist at the University of Toronto where he set up Canada’s first psychological research laboratory. Baldwin proposed a social psychological perspective in studying child development and believed that development occurs in stages. He explained that development of physical movement proceeds from simple to complex and eventually leads to more sophisticated mental processes. Jean Piaget (1896 – 1980) later advanced this idea further.

- Dr. Jean Clinton of McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario) is an internationally renowned advocate for children’s issues. Her research focus is in brain development and the role social relationships play in development.

- Dr. Fraser Mustard (1927-2011) created the “Canadian Institute for Advanced Research.” Of particular interest to Dr. Mustard was the role of communities in early childhood.

- Dr. Margaret McCain (1934- ), he prepared the influential report “The Early Years Study – Reversing the Real Brain Drain” for the Ontario government. The report emphasized promoting early child development centres for young children and parents by: boosting spending on early childhood education to the same levels as in K to 12, making programs available to all income levels, and encouraging local parent groups and businesses to set up these programs instead of the government, when possible.

- Dr. Stuart Shanker (1952- ) is Canada’s leading expert in the psychosocial theory of self-regulation.

- Richard Tremblay (1944- ) held the Canadian Research Chair in Child Development. His research focusses on the development of aggressive behaviour in children and whether early intervention programs can reduce chances of children turning to crime as adults.

- Dr. Mariana Brussoni of the University of British Columbia is currently active researching the developmental importance of risky play in childhood. Her focus is child injury prevention as well as the influence of culture on parenting in relationship to risky play and safety.

- In 1925, Professor Edward Alexander Bott established the St. George’s School for Child Study at the University of Toronto, which would eventually come to be known as The Institute for Child Study. It has been and continues to be, highly influential in developing Ontario’s early childcare and education system.

- Dr. Mary Ainsworth (1913-1999) developed the Strange Situation test, grew up in Toronto, ON. She attended University of Toronto where she earned her masters degree, and PhD in Psychology.

- Statistics Canada, in partnership with Human Resources Development Canada, undertook a major Canadian research initiative in 1994 titled “National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY)”. Researchers tracked multiple variables affecting children’s emotional, social and behavioural development over a period of time, using both longitudinal and cross-sectional sampling. Families from all provinces and territories were included with the exception of families living on First Nations reserves, in extremely remote areas of Canada and full-time members the Canadian Armed Forces. These exclusions should be kept in mind when extrapolating the data.

- Dr. Sheri Madigan of the University of Calgary holds Canada Research Chair in Determinants of Child Development. Her research explores “integrating methodological and statistical approaches that will help us understand the causes and consequences of typical and atypical child development” (Canada Research Chairs, 2021).

This is just a small selection of Canadian researchers who have contributed, and continue to contribute, to our knowledge of how best to support the development of young children.

Optional: Want to learn more?

To learn more about research methods: Research in Lifespan Development (Lumen Learning, n.d.).

To learn more about development: Introduction to Child Development (Pye, Scoffin, Quade & Krieg, 2022).

Summary

This has been an introduction to the theories and themes relating to our child development course. We will get into more detail as the weeks go on, and we cover each area and domain of development.

In this chapter we looked at:

- The major theories of child development.

- Different forms of attachment.

- Ecological Systems Theory.

References

Association for Child and Youth Care Practice. (2010). Competencies for Professional Child & Youth Work Practitioners. https://acycp.org/images/pdfs/2010_Competencies_for_Professional_CYW_Practitioners.pdf

Association for Child and Youth Care Practice. (2017). Standards for Practice of North American Child & Youth Care Professional. https://acycp.org/best-practice-standards

Baker, D. B. & Sperry, H. (2021). History of psychology. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/j8xkgcz5

Derksen, T. (2010). The Influence of Ecological Theory in Child and Youth Care: A Review of the Literature. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 1(3/4), 326-339. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs13/420102091

Government of Canada. (2023). Anti-racism Lexicon. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/systemic-racism-discrimination/anti-racism-toolkit/anti-racism-lexicon.html

Institute for Integrative Science and Health (n.d.). Two-eyed seeing. Retrieved from http://www.integrativescience.ca/Principles/TwoEyedSeeing/

Lally, M. & Valentine-French, S. (2023). Lifespan development: A psychological perspective. https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/540

Lumen Learning. (n.d.). Introduction to lifespan, growth and development. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/

Ontario Association of Child and Youth Care. (2017). Code of Ethics. https://oacyc.org/code-of-ethics/

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). Excerpts from ELECT: Foundational knowledge from the 2007 publication of “Early learning for every child today: A framework for Ontario early childhood settings”. Retrieved from https://www.dufferincounty.ca/sites/default/files/rtb/Excerpts-from-Early-Learning-for-Every-Child-Today.pdf

Paris, J., Ricardo, A., Rymond, D., & Johnson, J. (2020). Child Growth and Development. shared under a CC BY license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson (College of the Canyons).

Pegorraro Schull, C., La Croix, L., Miller, S.E., Sanders Austin, K., & Kidd, J.K. (2021). Early Childhood Literacy.

Pye, T., Scoffin, S., Quade, J., & Krieg, J. (2022). Child Growth and Development Canadian Ed. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/childgrowthanddevelopment/

OER Attributions

Child Growth and Development Canadian Ed by Tanya Pye; Susan Scoffin; Janice Quade; and Jane Krieg is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Early Childhood Literacy by Christine Pegorraro Schull; Leslie La Croix; Sara E. Miller; Kimberly Sanders Austin; and Julie K. Kidd is licensed under a Creative Commons

Lifespan development: A psychological perspective by Martha Lally and Susan Valentine-French is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Understanding the Whole Child Copyright © 2020 by Jennifer Paris; Antoinette Ricardo; and Dawn Rymond is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.