Physical Development: Infants and Toddlers

Chapter Objectives

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Categorize elements of physical growth (sensory, motor, perception)

- Consider the factors that contribute to physical growth

Introduction

Welcome to the story of physical development from infancy through toddlerhood! In Ontario, the Continuum of Development considers infants ranging in age from birth to two years (24 months), and toddlers from 14 months to 3 years (36 months) of age (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014).

When referring to infants and toddlers together in this text, we will focus on children under 3 years old. Researchers have given this part of the life span more attention than any other period, perhaps because changes during this time are so dramatic and so noticeable and perhaps because we have assumed that what happens during these years provides a foundation for one’s life to come.

The terms used throughout the literature refer to male and female development. For this course, this will refer to the gender assigned at birth.

How we support physical development in infants and toddlers is important to ensure they meet the milestones for this age group. Heredity is one thing, but the environment can also have a big influence.

Knowing what to look for is important (understanding the milestones or ‘targets’) so if we notice that a child needs more opportunities (or adaptations for disabilities or exceptionalities), we can use activities and play to support this development, in order to meet the milestone. We can adjust our activities, interventions, and approach to meet the child where they are at. This can also support the information we provide to caregivers and other professionals.

As Child and Youth Care Practitioners, our understanding of a child’s development can inform our work in many ways. Understanding milestones can give us insight of where a child could benefit from support.

Characteristics of Newborns and infants

Size

The average full-term newborn in Canada weighs about 7 pounds (or 3,530 grams, 12.5 ounces) at birth, and is about 51 cm or 20 inches in length. The average range is 46 cm (18 in.) to 56 cm (22 in.) 20 inches in length (HealthLinkBC, 2021).

Two hormones are very important to this growth process:

- Human Growth Hormone (HGH) which influences all growth except that in the Central Nervous System (CNS).

- Thyroid Stimulating Hormone influences growth in the CNS

Together these hormones influence growth in early childhood.

Want to learn more?

Proportions of the Body

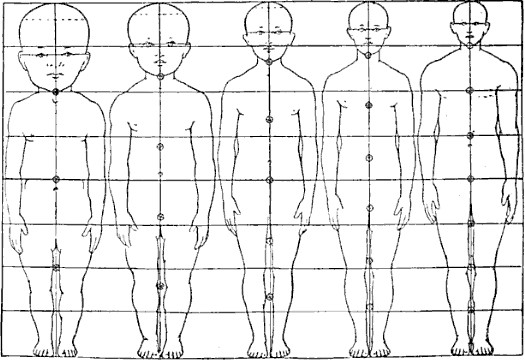

The increased weight that takes place in the first several years of life results in a change in body proportions. The head initially makes up about 50 percent of our entire length when we are developing in the womb.

At birth, the head makes up about 25 percent of our length (think about how much of your length would be head if the proportions were still the same!) By age 25 it comprises about 20 percent our length.

Imagine now how difficult it must be to raise one’s head during the first year of life! If you have ever seen a two to four-month old infant lying on the stomach trying to raise the head, you know how much of a challenge this is. Figure 1 below provides a visual representation.

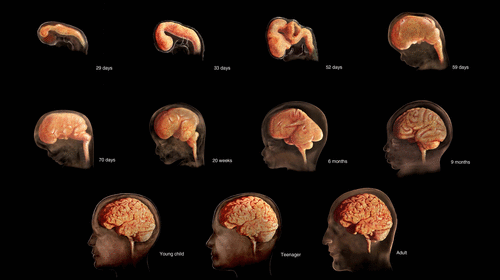

Some of the most dramatic physical changes that occur during this period happen in the brain (see figure 2 below). At birth, the brain is already about 25 percent its adult weight and this is not true for any other part of the body. By age 2, it is at 75 percent its adult weight, at 95 percent by age 6 and at 100 percent by age 7 years.

Brain Development

The basic building blocks of the brain are specialized nerve cells called neurons. These neurons proliferate before birth. In fact, a fetus’ brain produces roughly twice as many neurons as it will eventually need — a safety margin that gives newborns the best possible chance of coming into the world with healthy brains. Most of the excess neurons are shed in utero, leaving approximately 100 billion of these brain nerve cells left present at birth.

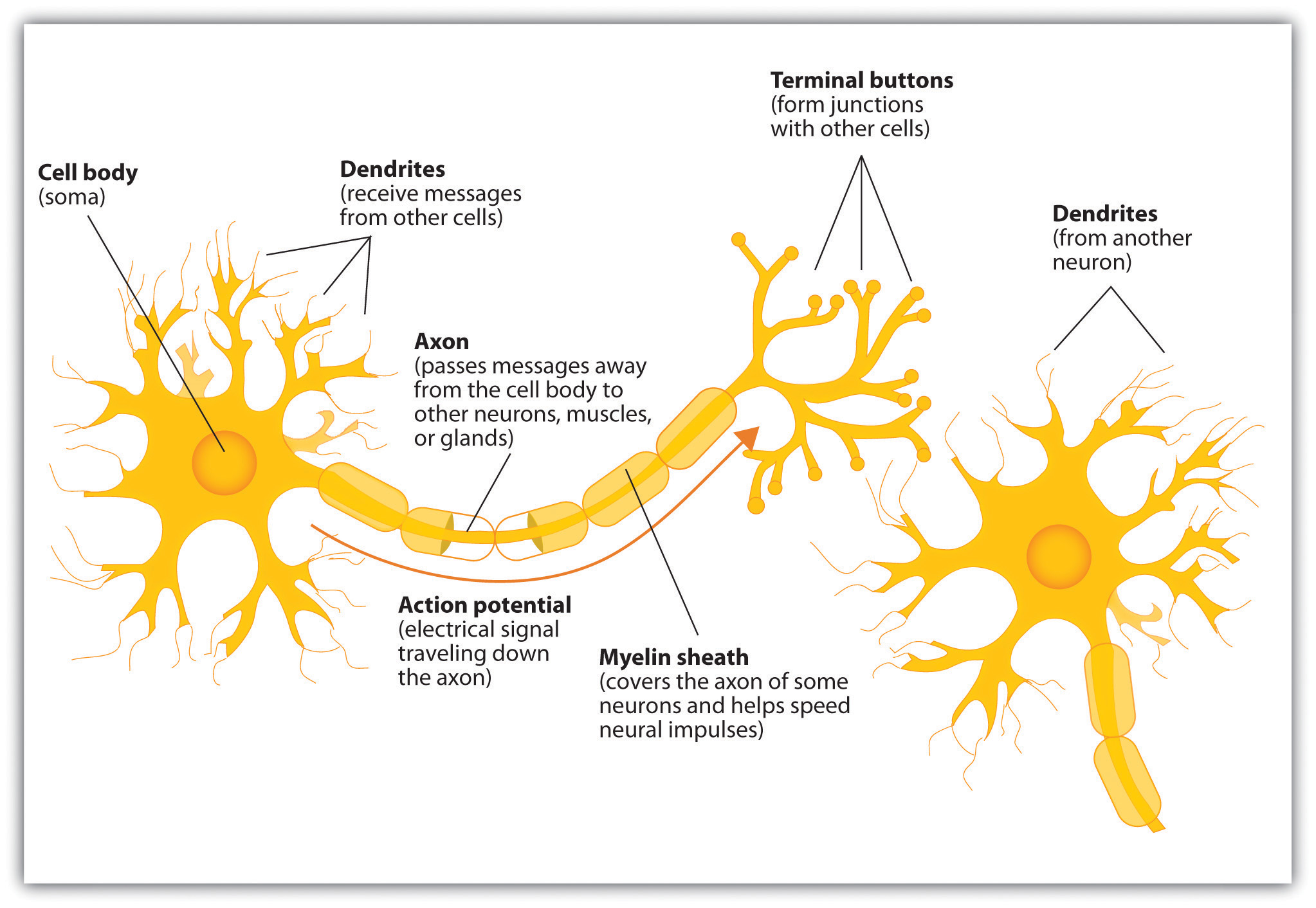

As a child matures, the number of neurons they have will remain relatively stable, but each brain nerve cell will grow, becoming bigger and heavier. This happens with both regular growth, and as the dendrites connect the neurons together (Graham & Forstadt, 2011) Figure 3 gives us an idea of what this might look like.

We’ll learn more about neurons and the brain when we cover cognitive development.

Appearance at Birth

Appearance at birth

Sleep

In a typical day 24-hour period, a newborn will eat, and have periods of wakefulness and sleep. For many reasons, this varies greatly between infants. It can take some time for an infant to fall into a somewhat recognizable and predictable schedule. A number of factors can influence this. The child’s temperament, their capacity to manage stressors, whether they are bottle fed or nursed, the environment, the experience of their families.

A newborn typically needs about 18 hours of sleep in a 24-hour period. The infant sleeps in several periods throughout the day and night, which means they wake often throughout the day and night (Salkind, 2005, as cited in Lally & Valentine-French, 2019) needing 12-16 hours of sleep from four to 12 months.

For toddlers, that number dips slightly to between 11-14 hours per day (Canadian Pediatric Society, 2018). There are many factors can support healthy sleep habits for infants and toddlers, including a regular routine, quiet time, and limited screen time before bed.

If you’d like to learn more (optional): Caring for Kids, a website created by the Canadian Pediatric Society (2018) has more information on sleep for infants and toddlers: https://caringforkids.cps.ca/handouts/pregnancy-and-babies/healthy_sleep_for_your_baby_and_child

Sensory Capacities

Throughout much of history, the newborn was considered a passive, disorganized being who possessed minimal abilities. However, current research techniques have demonstrated just how developed the newborn is with especially organized sensory and perceptual abilities (Bornstein, 2005).

The brain interprets the information that the senses collect from the environment. When considering the senses, the Continuum of Development focuses on the five senses: vision, hearing, touch, taste, and smell.

Vision

The Continuum of Development focuses on the following four elements of visual sense development:

-

- Face Perception: showing a preference for simple face-like patterns by looking longer, responding to emotional expressions with facial expressions and gestures, and/or turning and looking at familiar faces;

- Pattern Perception: showing a preference for patterns with large elements, showing a preference for increasingly complex patterns, visually exploring borders and/or visually exploring entire object;

- Visual Exploration: tracking moving objects with eyes, and/or looking and searching visually;

- Visual Discrimination: scanning objects and identifying them by sight.

(Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014)

The womb is a dark environment void of visual stimulation. Consequently, vision is the most poorly developed sense at birth and time is needed to build those neural pathways between the eye and the brain. Newborns typically cannot see further than 8 to 16 inches away from their faces (which is about the distance from the newborn’s face to the mother/caregiver when an infant is breastfeeding/bottle-feeding) and their visual acuity is about 20/400, which means that an infant can see something at 20 feet that an adult with normal vision could see at 400 feet. Thus, the world probably looks blurry to young infants.

When viewing a person’s face, newborns do not look at the eyes the way adults do; rather, they tend to look at the chin – a less detailed part of the face. However, by 2 or 3 months, they will seek more detail when exploring an object visually and begin showing preferences for unusual images over familiar ones, for patterns over solids, for faces over patterns, and for three- dimensional objects over flat images.

Newborns have difficulty distinguishing between colours, but within a few months, they are able to discriminate between colours as well as adults do. Sensitivity to binocular depth cues, which require inputs from both eyes, is evident by about 3 months and continues to develop during the first 6 months. By 6 months, the infant can perceive depth perception in pictures as well (Sen, Yonas, & Knill, 2001, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Infants who have experience crawling and exploring will pay greater attention to visual cues of depth and modify their actions accordingly (Berk, 2007, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

The Ontario Association of Optometrists (n.d.) recommends infants to “have their first eye exam at 6 months old, again at 2-3 years old, and every year after that.” In Ontario, annual eye exams are covered by OHIP for ages zero to 19 through the Eye See…Eye Learn® Program.

Hearing

The Continuum of Development focuses on the following two elements of auditory sense development.

-

- Auditory Exploration: making sounds by shaking and banging objects; turning to source of a sound, responding to familiar sounds with gestures and actions, and/or responding by turning towards a sound even when more than one sound is present;

- Auditory Discrimination: touching, rubbing, squeezing materials. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014)

Newborns also prefer their mother’s voices over another female when speaking the same material (DeCasper & Fifer, 1980, as cited by Paris et al., 2021). Additionally, they will register in utero specific information heard from their mother’s voice (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

The infant’s sense of hearing is very keen at birth. An infant can distinguish between very similar sounds as early as one month after birth, and can distinguish between a familiar and unfamiliar voice even earlier. Additionally, infants are innately ready to respond to the sounds of any language, but some of this ability will be lost by 7 or 8 months as the infant becomes familiar with the sounds of a particular language and less sensitive to sounds that are part of an unfamiliar language.

Typically, by age two to three years, toddlers can understand differences in meaning such as directions including stop and go (City of Toronto, 2024), and can follow simple directions.

Touch and Pain

Immediately after birth, a newborn is sensitive to touch and temperature, and is also highly sensitive to pain, responding with crying and cardiovascular responses (Balaban & Reisenauer, 2013, as cited by Paris et al., 2021).

Many areas of the infant’s body respond reflectively when touched. Touching an infant’s cheek, mouth, hand and foot produces reflexive movements, signifying that the infant feels those touches. Immediately after birth, a newborn is sensitive to touch and temperature, and is also highly sensitive to pain, responding with crying and cardiovascular responses (Balaban & Reisenauer, 2013, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

Taste and Smell

Studies of taste and smell demonstrate that babies respond with different facial expressions, suggesting that certain preferences are innate. Newborns can distinguish between sour, bitter, sweet, and salty flavors and show a preference for sweet flavors. Newborns also prefer the smell of their mothers. An infant, only 6 days old is significantly more likely to turn toward its own mother’s breast pad than to the breast pad of another baby’s mother (Porter, Makin, Davis, & Christensen, 1992, as cited by Paris et al., 2021), and within hours of birth, an infant also shows a preference for the face of its own mother (Bushnell, 2001; Bushnell, Sai, & Mullin, 1989, as cited by Paris et al., 2021).

Infants seem to be born with the ability to perceive the world in an intermodal way; that is, through stimulation from more than one sensory modality. For example, infants who sucked on a pacifier with a smooth surface preferred looking at visual models of a pacifier with a smooth surface. But those that were given a pacifier with a textured surface preferred to look at a visual model of a pacifier with a textured surface (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019, p. 76-77).

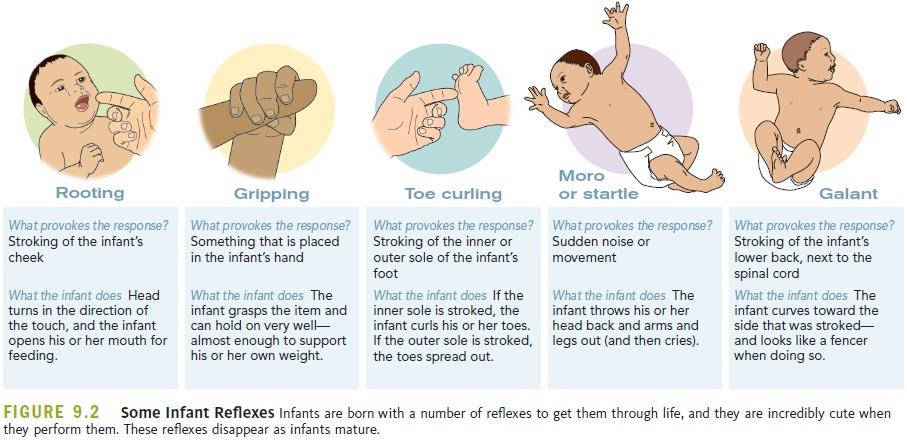

Reflexes

Newborns are equipped with a number of reflexes, which are involuntary movements in response to stimulation. Some of the more common reflexes, such as the sucking reflex and rooting reflex, are important to feeding. The grasping and stepping reflexes are eventually replaced by more voluntary behaviours. Within the first few months of life these reflexes disappear, while other reflexes, such as the eye-blink, swallowing, sneezing, gagging, and withdrawal reflex stay with us as they continue to serve important functions (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019, p. 73).

These movements occur automatically and are signals that the infant is functioning well neurologically. Within the first several weeks of life these reflexes are replaced with voluntary movements or motor skills.

Figure 5.6: (Image: https://www.sutori.com/en/item/untitled-4f52-ab3f)

As discussed earlier, the Continuum of Development is a guide, produced by the Ontario Ministry of Education, that identifies sequences of development across five domains. A domain is a broad area or dimension of development. One of the five domains outlined in the Continuum of Development is Physical. Physical skills learned by an infant are: Gross Motor Skills, Fine Motor Skills, Senses and Sensory Motor Integration (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014).

Gross Motor Skills

Gross motor skills are voluntary movements which involve the use and coordination of large muscle groups and are typically large movements of the arms, legs, head, and torso. They are also referred to as large motor skills. These skills begin to develop first. Examples include moving to bring the chin up when lying on the stomach, moving the chest up, rocking back and forth on hands and knees, and then locomotion. It also includes exploring an object with ones feet as many babies do as early as 8 weeks of age if seated in a carrier or other device that frees the hips. This may be easier than reaching for an object with the hands, which requires much more practice (Berk, 2007, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Sometimes an infant will try to move toward an object while crawling and surprisingly move backward because of the greater amount of strength in the arms than in the legs! This also tends to lead infants to pull up on furniture, usually with the goal of reaching a desired object. Usually, this will also lead to taking steps and eventually walking (Leon, n.d.).

When considering gross motor movements, the Continuum of Development focuses on the following:

- Reaching and holding: reaching towards objects as well as reaching and holding with palmar grasp;

- Releasing objects: dropping and throwing objects;

- Holding Head up: lifting one’s head while held on a shoulder;

- Lifting upper body: lifting one’s upper body while lying on the floor;

- Rolling: rolling from side to back and rolling from back to side;

- Sitting: sitting without support;

- Crawling: crawling on hands and/or knees;

- Pulling self to stand: using objects/people to pull self to standing position;

- Cruising: walking while holding onto objects;

- Walking: moving on one’s feet, unassisted, with a wide gait;

- Strength: increasing strength in gross motor skills

- Coordination: using different body parts at the same time, smoothly and efficiently. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014)

For toddlers, early childhood is a time when children are especially attracted to motion and song. Days are filled with moving, jumping, running, swinging and clapping, and every place becomes a playground. Even the booth at a restaurant affords the opportunity to slide around in the seat or disappear underneath and imagine being a sea creature in a cave! Of course, this can be frustrating to a caregiver, but it’s the business of early childhood.

Children may frequently ask their caregivers to “look at me” while they hop or roll down a hill. Children’s songs are often accompanied by arm and leg movements or cues to turn around or move from left to right. Running, jumping, dancing movements, etc. all afford children the ability to improve their gross motor skills.

Fine Motor Skills

More exact movements of the feet, toes, hands, and fingers are referred to as fine motor skills (or small motor skills). When considering fine motor skills, the Continuum of Development focuses on:

- Palmar grasp: holding objects with whole palm;

- Coordination: holding and transferring object from hand to hand and manipulating small objects with improved coordination;

- Pincer grasp: using forefinger and thumb to lift and hold small objects;

- Holding and using tools: making marks with first crayon, or using utensil to feed. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014)

For toddlers, fine motor skills are also being refined in activities such as pouring water into a container, drawing, coloring, and using scissors. Some children’s songs promote fine motor skills as well (have you ever heard of the song “itsy, bitsy, spider”?). Mastering the fine art of cutting one’s own fingernails or tying their shoes will take a lot of practice and maturation. Fine motor skills continue to develop in middle childhood, but for preschoolers, the type of play that deliberately involves these skills is emphasized.

Sensory Motor Integration

According to Brown (n.d.), sensory motor integration refers to a relationship between the sensory system (nerves) and the motor system (muscles). Also, it refers to the process by which these two systems (sensory and motor) communicate and coordinate with each other. In the process of developing sensory motor integration, a child first learns to move and then they learn through movement. Learning to move involves continuous development in a child’s ability to use the body with more and more skillful purposeful movement. Then, through this movement, the child learns more about themselves as they explores their environment. The process has three parts: (1) a sense organ receives a stimulus, (2) the nerves carry the information to the brain where the information is interpreted. (3) The brain then determines what response to make and transmits its instructions to the appropriate group of muscle fibres that carry out the response.

These two systems work together as a team, and if the sending nerve impulses are problematic, the brain will not receive the message, and if the breakdown is in the motor nerves, the muscles will not get a clear message and will not be able to give the correct motor response (Brown, n.d.). Interestingly, infants seem to be born with the ability to perceive the world in an intermodal way; that is, through stimulation from more than one sensory modality. For example, infants who sucked on a pacifier with either a smooth or textured surface preferred to look at a corresponding (smooth or textured) visual model of the pacifier. By 4 months, infants can match lip movements with speech sounds and can match other audiovisual events. Although sensory development emphasizes the afferent processes used to take in information from the environment, these sensory processes can be affected by the infant’s developing motor abilities. Reaching, crawling, and other actions allow the infant to see, touch, and organize his or her experiences in new ways (Brown, n.d).

Nutrition

According to the Canadian Pediatric Society (2020), for the first six months of life, breastfed infants will get what they need from their mother’s milk. Breast milk has the right amount and quality of nutrients to suit the baby’s first food needs. Breast milk also contains antibodies and other immune factors that help infants prevent and fight off illness. There are many reasons that mothers struggle to breastfeed or should not breastfeed, including: low milk supply, previous breast surgeries, illicit drug use, medications, infectious disease, and inverted nipples. Other mothers choose not to breastfeed. Some reasons for this include: lack of personal comfort with nursing, the time commitment of nursing, inadequate or unhealthy diet, and wanting more convenience and flexibility with who and when an infant can be fed. If breastfeeding is not an option, it is recommended that families seek out a store-bought iron-fortified infant formula for the first 9 to 12 months. This formula should be cow milk-based unless the infant cannot consume dairy-based products for medical, cultural or religious reasons. It should be noted that breastfed and bottle-fed infants adjust equally well emotionally (Ferguson & Woodward, 1999, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

According to the Canadian Pediatric Society (2020), while breast feeding and/or bottle feeding must still occur, at about 6 months of age most babies are ready to be introduced to solid foods.

They share that there are many ways to introduce solid food to ready infants. The first foods usually vary from culture to culture and from family to family. Healthy foods that the family is already eating are usually the best choice for the infant. It is recommended that families begin by introducing foods that contain iron, which babies need for many different aspects of their development.

According to the Dieticians of Canada (2020), it is recommended that children one years old and up follow the Canada Food Guide. Children need a balanced diet with food from all 3 food groups—vegetables and fruit, whole grain products, and protein foods. Children need 3 meals a day and 2 to 3 snacks (morning, afternoon and possibly before bed). Healthy snacks are just as important as the food served at meals.

Read more about the Canada Food Guide’s section on healthy eating for parents and children.

Child Malnutrition

There can be serious effects in the physical growth and development of children when there are deficiencies in their nutrition.

Failure to thrive is a term used to describe a child who seems to be gaining weight or height more slowly than other children of his or her age and sex (SickKids, 2009). There are many reasons why a baby might be small for their age; they do not always mean failure to thrive.

According to the National Institute of Health (as cited by SickKids, 2009), to be identified as an infant or toddler with failure to thrive, the child’s weight must be less than the third percentile on a standard growth chart, or 20% below the ideal weight for length or a fall-off from a previously established growth curve. There are a variety of causes for failure to thrive including maternal stress, diluted formula, feeding difficulties or specific health conditions. Infants who have untreated failure to thrive are at risk of slow development of physical skills, such as rolling over, standing, and walking (SickKids, 2009).

Summary

- Categorizing elements of physical growth (sensory, motor, perception)

- Considering the factors that contribute to physical growth

There are many areas of physical development that go beyond the scope of this course, you’re welcome to conduct your own research on the topic! Next, we move on to cognitive development.

References

Brown, E. (n.d.). Sensory motor integration. Retrieved from https://www.understanding-learning-disabilities.com/sensory-motor-integration.html

Bornstein, M. H. 2005. “Perceptual Development,” in Developmental Science: An Advanced Textbook(Fifth edition). Edited by M. H. Bornstein and M. E. Lamb. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Canadian Pediatric Society. (2020). Feeding your baby in the first year. Retrieved from https://www.caringforkids.cps.ca/handouts/pregnancy-and-babies/feeding_your_baby_in_the_first_year

Canadian Pediatric Society. (2018). Healthy sleep for your baby and child. https://caringforkids.cps.ca/handouts/pregnancy-and-babies/healthy_sleep_for_your_baby_and_child

Dieticians of Canada. (2020). Sample meal plans for feeding your baby. Retrieved from https://www.unlockfood.ca/en/Articles/Breastfeeding-Infant-feeding/Sample-meal-plans-for-feeding-your-baby.aspx

Graham, J. & Forstadt, L. (2011). Bulletin #4356, Children and brain development: What we know about how children learn. Retrieved from https://extension.umaine.edu/publications/4356e/

Government of Alberta. (2021). Physical growth in newborns. Retrieved from https://myhealth.alberta.ca/Health/Pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=te6295

HealthLinkBC. (2021). Physical Growth in Newborns. Retrieved from: https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/pregnancy-parenting/parenting-babies-0-12-months/newborns/physical-growth-newborns

Lally, M. & Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan development: A psychological perspective (2nd ed.). Retrieved from http://dept.clcillinois.edu/psy/LifespanDevelopment.pdf

Leduc, D. (Ed.). (2015). Well beings: A guide to health in child care (3rd ed.). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Paediatric Society.

Leon, A. (n.d.). Children’s development: Prenatal through adolescent development. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/document/d/1k1xtrXy6j9_NAqZdGv8nBn_I6-lDtEgEFf7skHjvE-Y/edit

Lumen Learning. (n.d.). Physical development. Retrieved from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/lifespandevelopment2/chapter/physical-development/

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). Excerpts from ELECT. Retrieved from https://countrycasa.ca/images/ExcerptsFromELECT.pdf

Queensland Government ( 2020). Breastfeeding: Signs of hunger. Retrieved from https://www.qld.gov.au/health/children/pregnancy/antenatal-information/breastfeeding-101/signs-of-hunger

SickKids. (2009). Failure to thrive. Retrieved from https://www.aboutkidshealth.ca/Article?contentid=514&language=English

OER Attributions

Child Growth and Development Canadian Ed by Tanya Pye, Susan Scoffin, Janice Quade, and Jane Krieg, published using Pressbooks by eCampus Ontario under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike)

Child Growth and Development by Paris, Ricardo, Rymond, & Johnson, through LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License/modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Dan Grimes, Portland State University

Lifespan Development by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 Lally, M. & Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan development: A psychological perspective (2nd ed.).